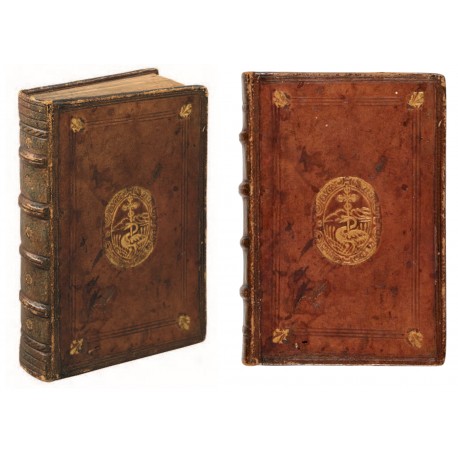

Bindings with the device of Guillaume Merlin

Guillaume Merlin was a son-in-law of Guillaume Godard, a printer-bookseller situated on the north bank of the Ile de la Cité, at the end of the Pont au Change, beside the L’Horloge de la Conciergerie and beneath “lenseigne de l’homme sauvage”. Godard was a senior member of the Parisian trade, libraire juré en l'université (from 1510), who specialised in liturgical books, especially books of hours (prayer books intended for the laity). By 1537, when his daughter Catherine married Guillaume Merlin, Godard was operating thirteen or fourteen presses, employing 250 workmen, and using 200 reams of paper each week.1 Unlike most colleagues, who contracted specific work to outsiders, Godard worked independently, keeping large stocks of materials (paper, matrices, woodblocks, binding leather, and gold leaf) on his premises, which gave him greater control over supply. An inventory taken in 1545 describes L’homme sauvage as composed of eight rooms spread over three floors, at once a residence, retail premises, workshop, and book warehouse (paper was stored in an annex nearby). A stock of 263,696 books is recorded, of which 148,717 are liturgical works, some described as “reliés” and “dorés” or “relié et prêt à dorer” (a doreur lodged in the attic of L’homme sauvage).2

In October 1538, Guillaume Merlin was named one of the twenty-four libraires-jurés, in succession to Guillaume Hardouyn, himself a specialist in books of hours.3 The inventory of 1545 provides no indication of his role in his father-in-law’s business, however by 1546-1547, Merlin appears to have taken over the shop. Merlin soon ceased printing, and became a merchant-bookseller.4 He kept the pictographic shop sign of an homme sauvage, but introduced new woodcut printer’s devices featuring a young swan (cygnet) standing amid bulrushes, its neck around the stem of a cross, enclosed by a scrollwork frame inscribed “In Hoc Cygno Vinces”.5 The earliest of these devices (69 x 96 mm; Renouard 760) reputedly first appeared in a folio Missal, use of Paris, issued in 1540 in association with Simon de Colines.6 Four smaller variants of the device are first recorded in 1552 (52 x 69 mm; Renouard 761), 1554 (31 x 41 mm; Renouard 762), 1553 (30 x 40 mm; Renouard 762bis), and 1552 (32 x 30 mm; not in Renouard).

From Left to right Renouard 760, 761, 762, 762bis (BaTyR 28152, 28154, 28156, 28494)

Unrecorded printer’s mark used for an Horae printed by Louis Tafforeau for Merlin in 1552 (for binding, see I-1 in List below)

Type I (detail from I-3), Type II (detail from II-1), Type III (detail from III-2)

Three binding stamps loosely associated with these devices have been recognised. Like their models, they vary orthographically: “Sugno” and “Cygno”, “Vinces” and “Vinses”. Claude Dalbanne believed the stamp employed on bindings here designated Type I was inspired by Renouard 762bis, except that the maker of the stamp has lettered “Vinses” instead of “Vinces”. Dalbanne assumes that the model for the stamp on the Type II bindings was Renouard 762.7

The purposes of so-called “publisher’s bindings” which feature the device or name of a publisher as part of their decoration were elucidated by E.P. Goldschmidt in his pioneering study of bookbinding.8 Such bindings are assumed to have been made for display in the publisher’s own bookshop, to advertise the business, or for sale to customers who preferred to buy their books ready bound. Other books displayed in his shop (publications of other printers) might be similarly bound for presentation or sale. Goldschmidt’s explanation accounts for why two copies of the same edition are found with Merlin devices on their bindings (I-3, II-3), and why a Merlin device appears on the covers of a book published by Sébastien Nivelle without Merlin’s involvement.9

It is possible that the binding stamps were applied at L’homme sauvage, not at a local bindery. The aforementioned inventory taken in 1545 described a doreur’s workshop in the attic of L’homme sauvage, where fifteen gilding presses were in use, and a large quantity of gold leaf was stored.10 Evidence that Guillaume Merlin retained that workshop in lacking; however, in 1564, he took on an apprentice, Jean Chrétien, who later became maître-doreur de livres.11

1. Jean-Baptiste-Louis Crevier, Histoire de l’Université de Paris depuis son origine jusqu’en l'année 1600 (Paris 1761), V, p.329 (“Guillaume Godard & Guillaume Merlin, imprimeurs, font plaider par leur avocat Boucherat, qu’ils, travaillent ordinairement à treize ou quatorze presses, qu’ils employent deux cens cinquante ouvriers, & qu’il leur faut par semaine près de deux cens rames de papier” [link]). Annie Parent, Les métiers du livre à Paris au XVIe siècle (1535-1560) (Paris 1974), considers 250 workmen to be excessive, reasoning that “en comptant cinq personnes pour une presse, 13 à 14 n’emploient guère plus de 70 à 100 apprentis et compagnons” (pp.209, 213). The date of Catherine Godard’s marriage to Guillaume Merlin is variously stated as 1534 and 1537 (cf. Parent, op. cit., pp.194, 209).

2. “Inventaire après décès de Geneviève Baudry, femme de Guillaume Godard, marchand libraire-imprimeur, bourgeois de Paris, demeurant actuellement sur le pont aux Changeurs, à l’enseigne de l’Homme sauvage, et occupant rue de la Vieille-Pelleterie les maisons à l'Image Saint-Jacques et à l’enseigne du Chaudron”, Paris, Archives nationales, Minutes et répertoires du notaire Jacques Filesac, (inventaires après décès), 2 juin 1545, MC/ET/IX/129 [link]. Madeleine Jurgens, Documents du Minutier central des notaires de Paris, Inventaires après décès, tome I, 1483-1547, catalogue (Paris 1982), p.301 no. 1255. See the analysis of this document by Parent, op. cit., pp.209-216, and for “l’imposant stock de matrices du libraire Guillaume Godard” see Rémi Jimenes, “L’atelier typographique à la Renaissance: local, organisation, équipement” in Le monde de l’imprimé en Europe occidentale (vers 1470-vers 1680) (Bréal 2021), pp.49-76, who has utilised the same 1545 inventory [link]. Virginia Reinburg (French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c.1400-1600, Cambridge 2012, p.32) supposes that the large numbers of books mentioned in booksellers’ post-mortem inventories are not complete copies, but instead numbers of quires.

3. Philippe Renouard, Répertoire des imprimeurs parisiens: libraires, fondeurs de caractères et correcteurs d'imprimerie: depuis l'introduction de l’imprimerie à Paris (1470) jusqu'à la fin du seizième siècle, edited by Jeanne Veyrin-Forrer (Paris 1965), p.304 [link]. The year of Guillaume Merlin’s birth is unknown; he died in 1574 (Rémi Jimenes, “Le monde du livre et l’Université de Paris (16e-17e siècles): l’apport des Acta rectoria” in Bulletin du bibliophile, 2017, pp.270-291 no. 119: “f. 91 Rect. Simon Bigot (24 mars- 23 juin 1574). Librarius unus. Robertus Le Mangnier magnus admissus per mortem honesti uiri Guillelmi Merlin senioris. Jurauit et souit bursas die XVIIIa junii” [link]).

4. Parent, op. cit., p.213. The last book issued under Godard’s name may be Heures a Lusaige de Besenson, tout au long sans requerir, published in 1547 (colophon: i[m]primees a Paris pour Guillaume godard libraire demourant sur le Pont au change Deuant lorloge du palays a lenseigne de Lhomme sauuaige [link]). in 1548, Godard made his will, however it seems that he was still living on 6 June 1553; see Parent, op. cit., pp.215-216. Renouard, Répertoire, op. cit., p.304 (“[Guillaume Merlin] se qualifie quelquefois typographus mais ne semble pas avoir été imprimeur.”).

5. Very few of Godard’s publications displayed a personal device, two deer supporting a shield bearing the initials “G G”, with “Guillaume Godart” lettered on banners below; see Philippe Renouard, Les marques typographiques parisiennes des XVe et XVIe siècles (Paris 1926), pp.112-113 no. 371 [link]; BaTyR: Base de Typographie de la Renaissance, 27809 [link]. The motto chosen by Merlin “In hoc signo vinces” (In this sign thou shalt conquer) refers to the Byzantine Emperor Constantine the Great’s celestial vision before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, when he saw Cygnus in the night sky, and decided to fight under the sign of the Christian Cross. According to E. Gordon Duff, A Century of the English book trade (London 1905), p.103, “the somewhat punning motto ‘In hoc cygno vinces’ … got [Merlin] into trouble” [link].

6. The edition is identified by Renouard as “1540. folio Missale ecclesie Parisiensis, in-folio”; see Les marques typographiques, op. cit., p.240 no. 760 [link]; BaTyR, 28152 [link]. The edition and supposed appearance of the swan device cannot be verified; however, the device features in a Missale ad usum ecclesie Parisiensis dated 1547 (1546 in colophon) printed by Jean Amazeur for Guillaume Merlin (Philippe Renouard, Imprimeurs & libraires parisiens du XVIe siècle, Paris 1964, pp.22-23 no. 31).

7. Claude Dalbanne, “Notes sur Guillaume I Merlin libraire parisien 1537-1571” in Gutenberg Jahrbuch 1958, pp.143-148 (pp.145, 147).

8. E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author's collection (London 1928), I, pp.40-41. See the discussions in this Notabilia file of bindings decorated with the devices of the publishers Jérôme de Marnef [link], Charles L’Angelier [link], Sébastien Gryphe [link], Jean Bogard [link].

9. Guillaume Merlin was a close friend of the printer Charlotte Guillard (he was among the beneficiaries of her estate) and through her with Sébastien Nivelle, who in 1549 married Guillard’s niece, Madeleine Baudeau (Merlin was a witness to their marriage contract). Merlin and Nivelle (1525?-1603) became frequent collaborators. Philippe Renouard, Documents sur les imprimeurs, libraires, cartiers, graveurs, fondeurs de lettres, relieurs, doreurs de livres, faiseurs de fermoirs, enlumineurs, parcheminiers et papetiers ayant exercé à Paris, de 1450 à 1600 (Paris 1901), pp.189-191, 202-203.

10. Parent, op. cit., p.213 (“Un doreur travaille à demeure, dans le grenier de l’Homme Sauvage, où sont entreposées quinze presses à dorer et ‘901 quarterons de feuilles d’or … valant chacun cent 32 st’.”).

11. Renouard, Documents, op. cit., p.54. Cf. Ernest Thoinan, Les relieurs francais (1500-1800): biographie critique et anecdotique (Paris 1893), p.230 (“[Chrétien] fit son apprentissage chez Guillaume Merlin, un des grands libraires du XVIe siècle, qui fut même libraire juré de l’Université en 1538. Ceci donne à croire que Merlin avait chez lui un atelier de reliure complet, puisqu’on y faisait même la dorure sur tranches.” [link]).

provisional census of bindings

I. Colin’s Type A, lettered: In Hoc Cygno Vinses

(I-1) Horae in lavdem dei, ac beatissime virginia Mariae, ad usum Romanum totaliter ad logum [almanac 1552-1564] (Paris: Louis Tafforeau for Guillaume Merlin, 1552)

Version of Merlin’s device on title-page not recorded by Renouard [link] or BaTyr [link]

provenance

● Musée d’art et d’industrie, Lyon (Dalbanne)

● Lyon, Musée des Tissus et des Arts décoratifs, Bibliothèque, R56 (Dalbanne, Colin)

literature

Claude Dalbanne, “Notes sur Guillaume I Merlin libraire parisien 1537-1571” in Gutenberg Jahrbuch 1958, pp.143-148 (p.145: “en veau brun dont les dos, refait … les plat sont bordés d’un filet à froid et ornés d’un cadre composé de trois filets à froid (un large entre deux minces), portant aux angles un fer aldin doré et au centre un fer-marque de Guillaume Merlin, poussé en or. Cette reliure, usagée et frottée, a ses deux fers-marque partiellement dédorés; cependant ils permettent de lire encore la légende en exergue: in hoc | cygno | vin | ses. Ce fer semble être plus spécialement inspiré de la marque de Merlin 762 bis (Renouard) [link], mais le graveur a commis la faute de mettre un S au lieu d’un C dans le mot vinces.”; Fig. 1: title-page; Fig. 2: f. X8, colophon)

Colin, op. cit. 1994, p.98 no. A-2

(I-2) Breviarium Romanum, ex Sacra potissimum Scriptura, et probatis sanctorum historiis nuper confectum. Ac denuo per eundem auctorem accuratius recognitum (Paris: Widow of Thielmann Kerver [Yolande Bonhomme] for Guillaume Merlin, 1546)

Device on title-page Renouard 50 [link]; BaTyr 27528 [link] (in use by Denis Binet, 1598)

provenance

● Paris, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Réserve, 8 BB 643 INV 794 (opac Rel. veau brun, double encadrement estampé à froid, fleurons dorés dans les angles, médaillon central doré (marque de Merlin: “In hoc cygno vinces” avec un cygne), XVIe s.; imprint transcribed as “Parisiis. Ex officina vidue spectabilis viri Thielmanni Kerver [Yolande Bonhomme], in vico sancti Jacobi sub signo Unicornis. 1546” [link])

literature

W.H. Weale, Bookbindings and rubbings of bookbindings in the National Art Library, South Kensington. 2: Catalogue (London 1894), II, no. 540 [link]

Dalbanne, op. cit. 1958, pp.143-148 (p.145: “Le même fer [as in I-1 above], la comparaison minutieuse a pu en être faite, a été poussé sur un autre volume: Breviarium romanum …, Paris, Guillaume Merlin, 1546, in-12 (Bibl. Ste Geneviève, rés. BB 643) … toutefois les fleurons d’angle, bien que conçus comme un grand nombre de fleurons de ce genre, ne sont pas absolument les mêmes (Fig. 4). Nous verrons bientôt qu’il existe, très semblable au premier, un deuxième fer-marque de Merlin.”; Fig. 4: upper cover of binding, Fig. 5 title-page, with the imprint “Parisiis Ex officina Gulielmum Merlin, in Teloneorum ponte commorantis, ad insigne hominis Syluestris, 1546”)

Colin, op. cit. 1994, p.95 no. A-1 (“tranches dorées”)

(I-3) Loys Miré, La vie de Jesus Christ nostre seigneur composée & extraicte des quatre Evangelistes, reduictz en une continuelle sentence. Auec les Epistres & leçons qu’on lit a la Messe au long de l’année Par Loys Miré. Description de la Terre Saincte avec sa charte en petite forme reduicte, par (Paris: Sébastien Nivelle (En la rue sainct Iacques, a l’enseigne des Cigognes), 1553)

No device on title-page [link]

provenance

● Franciscans Sint-Truiden (OFM) (opac)

● Louvain, KU, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Maurits Sabbe Library, PN00641 (opac Non-contemp. binding blind- and gilt stamped calf, metal clasps, supralibros Guillaume Merlin, bookbinder in Paris “In hoc cygno vinces” [link])

literature

Unrecorded

II. Colin’s Type B, lettered: In Hoc Cygno Vinces

(II-1) probable remboîtage Hebraea, Chaldaea, Graeca et Latina Nomina virorum, mulierum, populorum, idolorum, urbium, fluviorum, montium, caeterorúmque locorum quæ in Bibliis leguntur restituta cum Latina interpretatione. Locorum Descriptio ex cosmographis. Index rerum et sententiarum (Paris: Robert I Estienne, 1537)

provenance

● unidentified owner; Claude Dalbanne (1877-1964) (?)

literature

Robert Brun, “Guide de l’amateur de reliures anciennes (Suite.)” in Bulletin du Bibliophile 1938, pp.60-66 (p.65, “Il s’agit d’une impression de Robert Estienne, Paris, 1537 (communiqué par M. Dalbanne)”)

Dalbanne, op. cit. 1958, pp.146-147 & Fig. 6 [probably a remboîtage, since according to Dalbanne’s report “recouvrait primitivement deux ouvrages, mais le second a été enlevé et remplacé par des feuilles blanches”]

Colin, op. cit. 1994, p.98 no B-1

(II-2) Hortulus animae, denuo repurgatus, in quo Horae beatissimae virginis Mariae secundum usum Romanum continentur cum plurimis orationibus devote dicendis [almanac 1569-1585] (Paris: Henri Coypel for Guillaume Merlin, 1569 [colophon 1570])

Device on title-page: Renouard 762 [link]; BaTyr 28156 [link]

provenance

● unidentified owner, inscription “Guilelmus Van Veldame Bruxellensis 1573” on title-page (opac)

● unidentified owner, inscription “Adrian Husman [Gandencis]” on pastedown (opac)

● Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine, Rés 8° 23889 (opac Reliure du 16e siècle en veau brun avec fer doré ovale copié sur la marque de G. Merlin [link])

literature

Brun, op. cit. 1938, p.65 (shelfmark incorrectly stated as “25889”)

Colin, op. cit. 1994, pp.98-99 no. B-2

(II-3) Loys Miré, La vie de Jesus Christ nostre seigneur composée & extraicte des quatre Evangelistes, reduictz en une continuelle sentence. Auec les Epistres & leçons qu’on lit a la Messe au long de l’année Par Loys Miré. Description de la Terre Saincte avec sa charte en petite forme reduicte, par (Paris: Sébastien Nivelle (En la rue sainct Iacques, a l’enseigne des Cigognes), 1553)

No device on title-page [image, link]

provenance

● Tournai, Bibliothèque de la ville

literature

Amable Wilbaux, Catalogue de La Bibliothèque de la ville de Tournai (Tournai 1860), I, p.176 no. 224 [dated 1553; link]

Eugène-Justin Soil de Moriamé & Adolphe Hocquet, Exposition des arts décoratifs anciens et du livre. Catalogue, mai-septembre 1930 (Tournai 1930), p.182 no. 91 (“Veau. Rectangle à filet; aux coins une fleur de lys d’or. Au centre, dans un ovale, un cygne à la croix passant dans la courbe du cou. Tout autour l’inscription: In hoc cygno vinces … Reliure française de William Merlin (1538-1570)”) [edition incorrectly dated 1533]

Colin, op. cit., p.99 no. B-3 [incorrectly dated 1533]

III. Colin’s Type C, lettered: In Hoc Svgno Vinces

(III-1) Heures à lusaige de Romme toutes au long sans rien requérir. Nouvellement imprimes a Paris pour Guillaume Merlin. 1553 [reportedly bound with other texts, including: “Vespere. Impr. a Paris par Jehan Amazeur pour Guill. Merlin” (8 ff.), “Hymni communes. Impr. pour G. Merlin” (8ff.); “Extraictz de plusieurs sainctz docteurs etc. Impr. pour G. Merlin” (24 ff.); almanac 1553-1561] (Paris: Jean Amazeur for Guillaume Merlin, 1553)

Device on title-page: Renouard 762 [link]; BaTyr 28156 [link]

provenance

● formerly Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Bibliotheek, 2508 H 22 [this volume lost; its replacement given the shelfmark Allard Pierson Depot, OTM: OK 61-2209 is bound in half-vellum, link]

literature

C.P. Burger Jr, “Het abecedarium als algemeen verbreid leerboekje, I” in Het Boek 16 (1927), pp.17-32 (pp.29-32, title-page and binding illustrated; latter captioned “Bandje van de Heures a l’usage de Rome, uitg. G. Merlin 1553 met uitgeversmerk op het plat”)

Colin, op. cit. 1994, p.99 no. C-2

(III-2) Heures Nostre Dame à l’usage d’Amiens toutes au long sans riens requerir [with: Sequuntur vesperę per omnes ferias dicendae cum Completorio; Les qvinze effvsions de sang de nostre sauueur & redempteur Iesuchrist (Paris: Nicolas Bruslé for Guillaume Merlin, 1562 [-1569])

Device on title-page: Renouard 762 [link]; BaTyr 28156 [link]

provenance

● Margaret Paige, early signature on endpaper

● Bernard Quaritch, London; their A catalogue of fifteen hundred books remarkable for the beauty or the age of their bindings (London 1889), item 158 (£7 7s; “18mo. printed in red and black, with woodcuts, in the original calf binding, gilt edges, with a device stamped in gold on the sides … This is an interesting binding, as the design on the sides is almost identical with the woodcut on the title-page. It represents the swan bearing the cross, with the punning motto In hoc signo vinces. - We may infer that Merlin was a binder as well as a publisher.” [link])

● Maurice Bridel, Lausanne; their Catalogue 11: Beaux livres du XVe siècle au XIXe siècle (Lausanne 1950), item 90 (CHF 800; “Charmante reliure de l’époque ou de l’éditeur décorée au centre de plats de la marque de G. Merlin, gardes modernes”)

● Bernard Quaritch, Catalogue 1437: Continental books & manuscripts (London 2018), item 31 (£15,000; “late nineteenth century morocco preserving the covers of the original Parisian binding of calf ruled in blind, corner fleurons stamped in gilt, with the printer Guillaume Merlin’s gilt device (with motto ‘in hoc sugno vinces’) in centre of covers; minor wear and some staining” [link]); Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair 16-18 November 2018 (London 2018), item 43 ($19,500 [link])

● Musinsky Rare Books, New York; their E-Catalogue 16: Recent acquisitions (New York [2019]), item 9 ($20,000; [link])

● T. Kimball Brooker (Bibliotheca Brookeriana #3305; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part V: Readers and their books, London, 10 December 2024, lot 1118, unsold against £8000-£10,000 estimate, link; reoffered by Sotheby's, Bibliotheca Brookeriana VIII, Paris, 3-17 December 2025, lot 164, link)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (€7630) [RBH pf2525-164]

literature

Unrecorded

IV. Unassigned bindings

(IV-1) Heures a lusage de Romme nouvellement imprimées (Paris: [? for] Guillaume Merlin [ca 1560])

provenance

● Léon Gruel (1841-1923)

● Philippe et Jean-Paul Couturier & Pierre Chrétien, Beaux livres anciens, manuscrits à miniatures du XVe siècle, incunables et livres à figures sur bois … Reliures provenant de la collection Léon Gruel et décrites dans son Manuel, Paris, 27-28 November 1967, lot 245 (“A Paris, pour Guillaume Merlin. Sans date (vers 1560), in-8, gothique, veau brun, fleurons dorés au dos, filets à froid et fleurons d’angles dorés sur les plats, marque dorée au centre, trace de fermoirs, tranches dorées … Divers pièces du même imprimeur ont été relies a la fin du volume. Cette reliure est, selon Gruel, la seule connue portant la marque de Guillaume Merlin. Elle fut achetée après la publication du ‘Manuel’”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 400) [result in Le Livre et l’Estampe, 53-54, p.122]

literature

Unrecorded

(IV-2) Hore in laudem beatissime virginis Marie, ad usum Romanum, una cum quatuor passionibus [reportedly bound with: La vie de madame saincte Marguerite vierge & martyre auec son oraison] (Paris: Nicolas Bruslé for Guillaume Merlin, 1567)

provenance

● Susan Minns (1839-1938)

● American Art Association, Illustrated catalogue of the notable collection of Miss Susan Minns of Boston, Mass.: books, bookplates, coins, curios, prints, illuminated manuscripts and horae, gathered over a period of half a century, New York, 2-23 May 1922, sale lot 338 (“contemporary calf, with the title device repeated on sides in gilt, gilt edges, binding rubbed and worn at corners and edges” [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($5.00) [ABPC, link]

literature

Unrecorded

(IV-3) Heures de nostre Dame à l’vsage de Romme en latin & en françois [bound with: Cy sont extraictes de plusieurs sainctz docteurs, le propostitions, dictz & sentences cōtenās les graces [&c.] du tressacré & digne sacrement de l’autel [edited by by François Picart] (1553); Extraictes des plusieurs sainctz (1553)] (Paris: Jean Amazeur for Guillaume Merlin, 1555 [colophon 1556])

provenance

● unidentified owner, inscription Paulus …therr, 1597 (?) on lower pastedown (opac)

● Francis Douce (1757-1834), armorial exlibris, bequeathed in 1834 (opac)

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce BB 84 (1) (opac 17th-century gold- and blind-tooled calf over pasteboards, with gilt-edged leaves. Intersecting triple fillets form frames. At each corner of the inner rectangle a fleuron, repeated, in gilt. On both covers, a centrpiece in gilt, being the device of Guillaume Merlin. Rebacked … device on binding, above (being the gilt version of the printed version on the title-page): see M. L-C. Silvestre, Marques typographique (Paris, 1867, repr. Amsterdam, 1971), no. 268 [i.e., Renouard 762bis; link] [link])

literature

Unrecorded