Georg von Logau (ca 1500-1553)

In previous posts we have mentioned some Germans who chose to continue their education at the Italian universities and became there patrons of bookbindings, sending their schoolbooks to be specially bound in the local shops [link]. The Silesian nobleman Georg von Logau (Logus), who in the years 1519-1538 attended the universities of Bologna, Rome, Padua, and Ferrara, is known by three such bindings, two acquired by him in Bologna and the other in Venice. They compare favourably with the luxurious bindings commissioned by Logau’s better-known contemporaries, the students Nikolaus Ebeleben, Damian Pflug, and Heinrich Castell, and suggest a bibliophile of equally refined taste.

Georg von Logau was the second son of Georg von Logau (1473-1541) of Schlaupitz (near Reichenbach in the Eulengebirge) and Margareta (von Rastelwitz? von Kottulinsky?).1 He was schooled in Neiße and in the summer of 1514 matriculated in the university of Kraków,2 where he was a pupil of the poet Valentin Eck, and as “Georgius Logus Nisenus” “optime indolis adolescentis” published a series of twelve distichs in Eck’s De versificandi arte opusculum (Kraków 1515). Logau won the favour of the humanists Johannes II and Stanislaus Thurzó, bishops of Breslau and Olmütz, who from June 1516 supported his studies at the university in Vienna.3 He developed there life-long ties with the professor of rhetoric, Joachim Vadian (Watt, 1484-1551), and published more poetry.4 Stanislaus Thurzó and Georg von Loxan, Logau’s cousin and later German pro-chancellor for Bohemia, enabled him to matriculate in 1519 at Bologna, where his teacher was the Ciceronian Lazzaro Bonamico. Logau was nominated Prokurator of the German Nation at Bologna in 1524.5 In 1525, he travelled to Rome, where he was a student of Pierio Valeriano, and (introduced by Georg Sauermann) came into contact with Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto in the Sodalitas Coritiana, through which he gained access to the highest church dignitaries, even to Pope Clement VII.

In 1526 or 1527, Logau journeyed home, passing through Bologna, from where he is said to have dispatched a volume of Horace to his friend, Kaspar Ursinus Velius,6 and through the Veneto, where he apparently commissioned a large cast bronze portrait medal (78mm). The lettering on its obverse records him as aged 24: georgivs logvs geor[gii] f[ilius] ex silesia germa an aeta xxiiii. On the reverse is a scene of Venus on her dove-drawn chariot, accompanied by her son Cupid, who draws his bow as Mercury descends from above, lettered around amor et mvtvvs ignis - ingenio conivnctvs.7

Georg von Logau, aged 24. Anonymous medallist (Antonio Vicentino?), 78mm

In 1528, Logau entered the service of Ferdinand I von Hapsburg, newly crowned King of Bohemia and Hungary, as a secretary and councillor. A collection of his poems, dedicated to King Ferdinand, was published at Vienna in 1529.8 Evidence of nascent bibliophilism are two special copies of the edition, issued on vellum, with the two large woodcuts of the dedicatee and author’s armorial insignia hand-coloured, and some dedicatory lines (ff. E1, I1) and verses (A1v) printed in gold letters. One presumably is the dedication copy;9 the other may be Georg’s personal copy.10

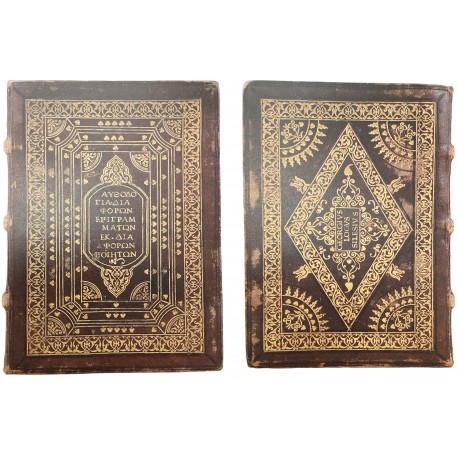

Logau travelled in Ferdinand’s entourage to the Imperial Diet in Augsburg (inaugurated by Charles V on 20 June 1530), where he met the brothers Raymond and Anton Fugger. Anton Fugger agreed to finance his return to Italy, and Logau arrived in Padua before September 1531.11 When he heard of the sudden death at Venice of the jurist and Greek scholar Gregor Haloander (Meltzer, d. 7 September 1531), Logau is said to have rushed there together with Lazzaro Bonamico (now professor of Latin and Greek in the Paduan Studio) for the purpose of inventorying Haloander’s library and preventing its disposal.12 He reputedly took away Haloander’s copy of the first printed edition of the Anthologia Graeca Planudea (Florence 1494) and had it sumptuously re-bound, with the title of the work in Greek letters on the upper cover, and georgivs logvs silesivs on lower cover.13

The binding on the Anthologia graeca (see no. 1 in list below) was attributed by Ilse Schunke to an anonymous Bolognese shop she designated the “Spiegel-Meister” on account of the work it executed for Dietrich (Theodor) von Spiegel, who matriculated at Bologna in 1524. Anthony Hobson renamed the shop the “German Students’ Binder” and established that it was active from about 1520 until the mid-1530s, when its materials and clients were taken over by a shop he named the “Pflug and Ebeleben Binder.” The bindings these two shops executed for German students typically showed the book’s title in the centre of the upper cover, and the owner’s name and often a date in the same place on the lower cover.14

Left Detail from a Venetian binding (1540) given to François I. Right Detail from Demosthenes (no. 2)

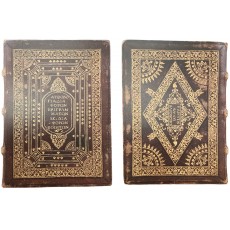

The Demosthenes (no. 2) was splendidly bound at Venice in an anonymous shop about the same date (ca 1534-1538), its gilt decoration following Ottoman models, with four cornerpieces of leafy tendrils and flowers, and a large, lobed centrepiece apparently identical to one used for the dedication copy of Serlio’s Il terzo libro nel qual si figurano, e descrivono le antiquità di Roma (Venice 1540).15

The Sophocles (no. 3) was bound in Bologna, either in the shop of the “German Students’ Binder” or in that of its successor, the “Pflug and Ebeleben Binder”.16

By August 1533 Logau was studying in Rome, where he met the young German scholar Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter (1506-1557), who gave him a transcript of a manuscript containing Latin poems on hunting and fishing (according to Logau, the original had been obtained in France by Sannazaro and brought to Naples). Georg edited the manuscript, which was published in February 1534 at the newly restored Aldine press in Venice with a dedication to Anton Fugger.17 Logau befriended in Rome some Italian Ciceronians attacked by Erasmus, and while there wrote a tract critical of Erasmus’s Ciceronianus, which circulated widely in manuscript, reaching Erasmus in May 1534.18

Returning to Silesia, Georg edited and dedicated to his other patron, Georg von Loxan, the collected verse of Basilio Zanchi,19 published a small volume of poetry in celebration of Loxan’s marriage,20 and contributed verses to Wolfgang Anemoecius (Winthauser’s) Epithalamion for that event.21 By 1536 he was again in Italy, and probably still there on 1 February 1538, when he was promoted doctor of civil law at the university of Ferrara.22 The university register identified him as “canonicus vratislaviensis et budissinensis, Ferdinandi Imperatoris Consiliarius”.23 Logau had been a canon of Breslau since 1529 and after he was ordained priest in 1541, he held a seat and a vote in the chapter.24 His father conceded to him a canonry with a large benefice in Stift St Peter Bautzen (Budissin).25 In 1540, Logau was appointed Propst of the Stiftskirche zum heiligen Kreuz in Breslau by royal command;26 and in 1552 he became canon in Großglogau. He remained until the end of his life in imperial service and continued to write elegies and epigrams for his friends and other humanists, among them Johann Faber, Franz Emerich, Kaspar Ursinus Velius, Johannes Lange, and Sigmund von Herberstein, and as a comes palatinus may have laureated Lange in 1548.27 Logau died on 11 April 1553 and was interred in the Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross in Breslau.28

No testamentary documents appear to have survived and the extent and character of Logau’s library remain unknown. He evidently possessed (briefly) a codex from the celebrated library at Buda of King Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490). In 1553, a translation by Johannes Lange of the Historia Ecclesiastica compiled by Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos (1256-1335) was published at the Basel press of Oporinus. In a prefatory note, Lange recounts the recent provenance of the codex, stating that it had been stolen “ante annos multos” from the royal library of Buda in Hungary and was in private ownership there at the time of the city’s conquest by the Ottomans in 1526. Taken by Turkish troops to Constantinople, it was found at a flea market (“in foro scrutario”) by Agostino Sbardellati, after 1548 bishop of Vác, who - according to a dedicatory poem by Logau contributed to Lange’s edition - gave it to Logau, who in turn presented it to Ferdinand I. Lange was then asked to translate the manuscript and he had finished the work by 1551.29 The codex was rebound in 1754 and no inscription or other evidence of Logau’s ownership has been reported.

bindings for georg von logau

(1) Anthologia diversorum epigrammatum [Greek] (Florence: Laurentius (Francisci) de Alopa, Venetus, 11 August 1494

provenance

● perhaps Gregorius Haloander (d. 7 September 1531) [see above]

● Georg von Logau, supralibros, his name georgivs logvs silesivs lettered on lower cover

● Friedrich Staphylus (1512-1564), armorial exlibris “Fridericus Staphylus Caesareus et Bavaricus Consiliarius”

● Benediktinerabtei Ottobeuren, inscription “Monasterii Ottoburani” on endleaf

● Leipzig, Stadtbibliothek, Rep. I. 4°. 56.a

literature

Robert Naumann, Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum qui in Bibliotheca Senatoria civitatis Lipsiensis asservantur (Grimma 1838), p.8 (“Ab initio nostri exemplaris in margine manu adscripta sunt scholia Graeca, quae iam habentur in ed. Wechel. Fol. 1. a. leguntur verba: Monasterii Ottoburanj, - In ligatura bene aurata impressum est nomen: georgivs logvs silesivs. Posteriori libri operculo agglutinata sunt variis coloribus picta insignia gentilitia Friderici Staphyli Caesarei et Bavarici Consiliarii” [link])

Aristide Calderini, “Scoli greci all’Antologia planudea” in Memorie del Reale Istituto Lombardo di Scienze e Lettere. Classe di Lettere e Scienze morali e storiche 22 (1912), pp.227-279 (p.236 [link])

Johannes Hofmann, “Ein venezianischer Bucheinband für Georg von Logau: Einen unbekannten deutschen Bücherfreund des XVI. Jahrhunderts” in Zeitschrift für Bücherfreunde, new series, 17 (1925), pp.66-68 (“Wir kennen bis jetzt aus Logaus Besitz nur den hier behandelten Einband” [link])

Johannes Hofmann, Kostbare Bucheinbände der Leipziger Stadtbibliothek und ihre Katalogisierung (Leipzig 1940), pp.30-31 (upper cover illustrated)

Ilse Schunke, “Die bibliophile Mission des Nikolaus von Ebeleben” in Imprimatur: Ein Jahrbuch für Bücherfreunde 11 (1952/1953), pp.150-161 (p.154 & Tafel 1)

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura Artistica in Italia nei Secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 1271 & Pl. 220

Ilse Schunke, “Die Renaissanceeinbandkunst in Bologna” in Beiträge zur Geschichte des Buches und seiner Funktion in der Gesellschaft. Festschrift für Hans Widmann zum 65. Geburtstag am 28. März 1973 (Stuttgart 1974), pp.252-268 (p.259, as bound by the “Spiegel-Meister”)

Konrad von Rabenau, Deutsche Bucheinbände der Renaissance um Jakob Krause (Brussels 1994), no. 42 (as bound by the “Manutius-Werkstatt, Venedig für Georg von Logau 1531”; errata (Bildband [p.8]), citing Schunke’s attribution to the “Spiegel-Meister”)

Anthony Hobson, “Bookbinding in Bologna” in Schede umanistiche, n.s. 1 (1998), pp.147-175 (p.157)

Anthony Hobson & Leonardo Quaquarelli, Legature bolognesi del Rinascimento (Bologna 1998), p.17 & no. 19 (as bound by “Il Legatore degli studenti tedeschi”)

Federico Macchi & Livio Macchi, Atlante della legatura italiana: il Rinascimento: XV-XVI secolo (Milan 2007), pp.30-31 & Tav. a-b

(2) Demosthenes, Demosthenous Logoi, duo kai exekonta. Libaniou sofisou, upotheseis eis tous autous logois. Bios Demo sthenous, kat'auton Libanion. Bios Demosthenous, hata Ploutarckon. Demosthenis Orationes duae & sexaginta. Libanii sophistae in eas ipsas orationes argumenta. Vita Demosthenis per Libanium. Eiusdem uita per Plutarchum (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, November 1504)

provenance

● Georg von Logau, supralibros, his name g[eorgius] logvs s[ilesius] eqves l l[egum] d[octor] lettered on lower cover

● Breslau, St Maria Magdalena Kirchenbibliothek, inkstamp “Ex. Bibl. ad. aed. Mar. Magdal.”

● Breslau, Stadtbibliothek, 2 N 140 [surviving books transferred 1946 to the Universitätsbibliothek [link]; untraced in that library’s opac]

literature

Alphabetischer Bandkatalog der Stadtbibliothek zu Breslau (1866-1930), Da-Dem, f.96 [link]

Johannes Hofmann, “Dies diem docet! Ein zweiter venezianischer Logau-Einband” in Zeitschrift für Bücherfreunde, new series, 17 (1925), pp.103-104 [link]

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), p.131 (“[Logau] owned two elaborate bindings, one of which, very oriental in character, is certainly Venetian; the other has some resemblance to Schlick's binding [copy of Quintus Asconius Pedianus, Expositio in IIII orationes M. Tullii Cic. contra C. Verrem & in orationem pro Cornelio (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, 1522); illustrated by Ludwig Bickell, Bookbindings from the Hessian historical exhibition: illustrating the art of binding from the XVth to the XVIIIth centuries (Leipzig 1893), Pl. XIIIA)] and is probably Bolognese”)

(3) Sophocles, Sophocleous Tragodiai hepta metexegeseon. Sophoclis Tragaediae septem cum commentariis (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, August 1502)

provenance

● Georg von Logau, supralibros, his name georgivs logvs silesivs lettered on lower cover within a roundel

● unidentified owner, inscription “Georgii Fasligium… Anno domini 1633” on pastedown

● Christian Gryphius (1649-1706), rector of the Maria-Magdalenen-Gymnasium in Breslau, inscription “Christian Gryphium vratislav” on title-page and “Pariss Constat. 8 fl. A[nno] MDCLXXVII” (not traced in sale catalogue, Catalogus Bibliothecae Gryphianae, Breslau, May 1707 [link])

● Peter Kiefer, Auktion 63: Bücher & Graphik, Alte und Moderne Kunst, Pforzheim, 5-6 October 2007, lot 415 (“Exemplar aus der Bibliothek des humanistischen Dichters Georg von Logau (vor 1500-1553), Superintendent in Breslau. - Tit. unterer Blattrand angesetzt, verso bis knapp an die Schrift. Tls. leicht wasserrandig, Gelenke etw. brüchig. Die Bl. der Lage v tls. untereinander verbunden. Hs. Besitzverm. von 1633 a. Innendeckel. Vors. erneuert.” [link])

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (€7500) [RBH 63-415]

● Bibliopathos, Verona, 2019

● T. Kimball Brooker (Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0819)

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection: N-Z, New York, 25 June 2025, lot 1435 ($31,750) [RBH N11571-1435]

1. The uncertain year of Georg’s birth is often recorded as ca 1495 (Heinrich Grimm, “Logau, Georg von” in Neue Deutsche Biographie 15 (1987), pp.117-118 [link]); it more likely was ca 1500-1505. For the identity of Georg’s mother, compare Friedrichs von Logau sämmtliche Sinngedichte, edited by Gustav Eitner (Tübingen 1872), pp.695-696 (as Rastelwitz) [link] and Genealogisches Handbuch der Adeligen Häuser - Adelige Häuser A. Band III (Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Band 15 der Gesamtreihe) (Glücksburg 1957), p.316 (von Kottulinsky).

2. Enrolled as “Jeorgius Georgii de Swednycz d. Wrat., 1 mensis Maii”; see Antoni Gasiorowski, Metrica seu album Universitatis Cracoviensis a. 1509-1551: Bibliotheca Jagellonica cod. 259 (Warsaw 2010), p.53. Gustav Bauch, “Deutsche Scholaren in Krakau in der Zeit der Renaissance 1460 bis 1520” in Jahresbericht der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für vaterländische Kultur 78 (1900), pp.2-76 (p.71).

3. Willy Szaivert & Franz Gall Die Matrikel der Universität Wien (Graz 1954), II, p.431 (enrolled as “Georgius Logus”; in a later hand “Poeta et cano[nicus] Vra[tislaviensis]”); Repertorium Academicum Germanicum (rag), q.v. Georg von Logau [link].

4. Logau contributed a four-distich “ad lectorem exhortatio” to a collection of poetry by Baptista Pallavicino, Filippo Beroaldo, Pico della Mirandola, and others (Leonhard & Lukas Alantsee, March 1516; VD16 ZV 7945); a phalaecium to Vadian’s Aegloga, cui titulus. Faustus (Johann I Singriener, 1517; VD16 ZV 20525); three distichs to Johannes Camerarius’s edition of Claudius Claudianus (Johann I Singriener, 1517; VD16 C 4041); four distichs to Johannes Gremper’s edition of Gregorius Nyssenus (Leonhard & Lukas Alantsee, December 1517; VD16 G 3120); and poetry of various kinds to Kaspar Ursinus Velius’s Epistolarum et Epigrammatum liber (Johann I Singriener, 1517; VD16 U 350); Vadian’s edition of Pomponius Mela (Johann I Singriener, 1517; VD16 M 2310, VD16 V 7, VD16 V 26); and Vadian’s De Poetica et Carminis ratione, Liber (Johann I Singriener, 1518; VD16 V 33).

5. E. Friedlaender & C. Malagola, Acta nationis Germanicae (Berlin 1887), p.291 [link]; Gustav Knod, Deutsche Studenten in Bologna (1289-1562): Biographischer Index zu den Acta nationis germanicae Universitatis Bononiensis (Berlin 1899), pp.311-312 no. 2144 [link].

6. For this gift, see Michael Denis, Wiens Buchdruckergeschichte bis MDLX (Vienna 1782), p.257 [link]; Joseph Aschbach, Geschichte der Wiener Universität (Vienna 1865), II, p.331 [link]; Knod, op. cit., p.311.

7. The only recorded example is in Brescia, described by Prospero Rizzini, Illustrazione dei civici musei di Brescia: serie italiana. Secoli XV a XVIII (Brescia 1892), pp.60-61 no. 26 [link], and illustrated by Georg Habich, “Zwei Medaillen auf den schlesischen Dichter Georg Logus” in Archiv für Medaillen- und Plakettenkunde 5 (1925-1926), pp.144-147 [link]. Max Bernhart, “Nachträge zu Armand” in Archiv für medaillen- und plaketten-kunde 5 (1925-1926), pp.69-90 (p.78) [link]. Habich attributed it to the Modenese die-maker Niccolo Cavallerino. G.F. Hill withdrew from Cavallerino’s oeuvre all the cast medals, attributing them instead to Antonio Vicentino; see his “Nicolo Cavallerino et Antonio da Vicenza” in Revue Numismatique 19 (1915), pp.243-248, and Medals of the Renaissance (London 1920), p.66 [link]. The earliest medal associated with Antonio Vicentino depicts Giovanni Battista Casali before his appointment 18 September 1527 as Bishop of Belluno. Giuseppe Toderi sustained the attribution to Antonio Vicentino in his Le medaglie italiane del XVI secolo (Florence 2000), no. 900 & Tav. 196, but with the improbable date of 1530-1540. Logau subsequently commissioned a smaller portrait medal (28mm) of which only uniface examples lettered g. logvs silesivs poeta et eqves germanvs are known. It is attributed to the South German medallist Ludwig Neufahrer by Habich, Die deutschen Medailleure des XVI. Jahrhunderts (Halle a.d. Saale 1916), p.109, and Günther Probszt-Ohstorff, Ludwig Neufahrer: ein Linzer Medailleur des 16. Jahrhunderts (Vienna 1960), p.91. Drawings headed “Nummus in honorem Georgii Logi cusus” in a printed book in Wrocław (see note 10 below) suggest that examples were circulated with this portrait and lettering and a reverse depicting the goddess Flora. An anonymous painted portrait is discussed by Ewa Houszka, “Bildnis des Georg von Logau” in Via Regia: 800 Jahre Bewegung und Begegnung: 3. Sächsische Landesausstellung (Dresden 2011), p.323.

8. Georgii Logi Silesii ad inclytum Ferdinandum Pannoniae et Bohemiae regem invictissimum hendecasyllabi, elegiae et epigrammata (Vienna: Hieronymus Vietor, 1529). Péter Kasza, “Pulchre convenit improbis cinaedis. Über die Gedichte des Schlesischen Humanisten Georg von Logau (Georgius Logus)” in Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 54 (2014), pp.157-165. The second of its three parts is dedicated to Bernhard von Cles and the third to Gabriel von Salamanca-Ortenburg. At the end of the collection Logau prints a number of testimonials, including a letter of Paolo Giovio (9 January 1526) and one of Pope Clement VII to King Lajos II of Hungary (24 November 1525; see Brevia Clementina: the Hungarian-related breves of Pope Clement VII, edited by Gabor Némes (Budapest 2015), no. 111).

9. Location unknown. The upper cover of this copy is lettered ferdinandi regi and the lower g logus dedicavit. It was sold by Puttick & Simpson, Bibliotheca Sunderlandiana, London, 17-27 July 1882, lot 7533 [link], passing thereafter through the catalogues of the London booksellers Bernard Quaritch, including A Catalogue of fifteen hundred books remarkable for the beauty or the age of their bindings (London 1889), item 1412 [link]; Catalogue 166: Examples of the art of book-binding (London 1897), item 260 [link].

10. Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej we Wrocławiu, E.XXI, 388 [link]. Gustav Bauch, Der humanistische Dichter George von Logau (Breslau 1896), p.18, speculates that this vellum copy belonged to the poet himself [link]. It was examined by Peter Schaeffer, “Humanism on Display: The Epistles Dedicatory of Georg von Logau” in The Sixteenth Century Journal 17 (1986), pp.215-223 (p.223), who reports another copy (on paper?) in the Houghton Library, Harvard University (Typ 522 29.530), likewise with the armorial woodcuts hand-coloured.

11. Letter to Ioannes Dantiscus, subscribed by Logau at Padua, 18 September (“1530” was inferred by the editors of the Corpus of Ioannes Dantiscus’ Texts & Correspondence, Letter #549 [link]).

12. Bauch, op. cit., p.21 [link]. Bauch’s authority seems to be the letter of Viglius Zuichemus to Amerbach written at Padua, 18 November 1531; see now Alfred Hartmann, Die Amerbachkorrespondenz, IV. 1531-1536 (Basel 1953), no. 1584 [link]. Eduard Flechsig, Gregor Haloander (Zwickau 1872), p.20, cites a letter of the Nuremberg publisher Johann Petreius to Stephan Roth, Stadtschreiber of Zwickau, written in 1534, in which Petreius reported that “Haloandri Bücher und Habseligkeiten in Italia wären laut Briefen von Julio Pflugk unter gottloser Leute Hände gerathen und distrahirt worden” (according to letters from Julius Pflug, Haloander's books and belongings in Italy had fallen into the hands of ungodly people and been diverted [link]). Compare Julius Pflug. Correspondance, recueillie et éditée avec introduction et notes par Jacques V. Pollet (Leiden 1969), I, p.232 (letter no. 53, Ziegler to Pflug) and p.323 (letter no. 95, Pflug to Roth).

13. No evidence in the volume of Haloander’s ownership is reported, and neither Bauch (op. cit.) nor Hofmann (op. cit.) suggested that Georg obtained books from Haloander’s library. That inference is made by Konrad von Rabenau, Deutsche Bucheinbände der Renaissance um Jakob Krause (Brussels 1994), no. 42, who writes “Den wertvollen frühhumanistischen Druck aus Florenz wird er 1531 aus dem Nachlaß des Juristen und Gräzisten Gregorius Haloander erworben haben, da er damals eigens nach Italien gereist ist, um dessen Bibliothek zu inventarisieren und zu erhalten. Der großen Erwerbung hat er mit einem neuen Einband eine angemessene Gestalt geben wollen.” A copy of Simplicius, Symplikiou Exegesis eis to tou Epiktetou Encheiridion (Venice: Giovanni Antonio Nicolini da Sabbio & brothers, 1528) with Haloander’s name in gilt on the lower cover is now Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct.K.4.16 [link], via Ferdinand Martins Mascarenhas, Bishop of Faro, whose library was looted in 1596 by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, then donated to Thomas Bodley; see Fine bindings 1500-1700 from Oxford libraries: catalogue of an exhibition (Oxford 1968), no. 20, and Anthony Hobson, “Bookbinding in Bologna” in Schede umanistiche, n.s. 1 (1998), pp.147-175 (p.157 & Fig. 7), attributing the binding to the German Students’ Binder.

14. Ilse Schunke, “Foreign bookbindings, II. Italian Renaissance bookbindings: 1. Bologna 1519” in The Book Collector 18 (1969), pp.200-201; Anthony Hobson, “Bookbinding in Bologna” in Schede umanistiche, n.s. 1 (1998), pp.147-175 (pp.157-159: “The ‘German Students’ Binder’, c.1520-c.1535”); Anthony Hobson & Leonardo Quaquarelli, Legature bolognesi del Rinascimento (Bologna 1998), pp.16-18 (“Il ‘legatore degli studenti tedeschi’”).

15. Anthony Hobson, Humanists and bookbinders: the origins and diffusion of the humanistic bookbinding 1459-1559 (Cambridge 1989), pp.152-153 Fig. 120; J.M. Rogers, “Ornament prints, patterns and designs East and West” in Islam and the Italian Renaissance, edited by Charles Burnett & Anna Contadini (London 1999), pp.133-165 (p.139 & Fig. 17).

16. The Bolognese binders were equipped with a number of bust-portrait stamps of poets; see Hobson, op. cit. 1989, pp.123-125, and p.164 Fig. 130 for a Bolognese binding of ca 1545 featuring a small stamp of Aeolus.

17. Hoc volumine continentur poetae tres egregij nunc primum in lucem editi, Gratij qui Augusto principe floruit, de uenatione lib.I. P. Ouidij Nasonis Halieuticon liber acephalus. M. Aurelij Olympij Nemesiani cynegeticon lib.I. Eiusdem carmen bucolicum. T. Calphurnij Siculi bucolica. Adriani cardinalis uenatio (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Heirs of Andrea Torresano, February 1534). Paul Lehmann, Eine Geschichte der alten Fuggerbibliotheken (Tübingen 1956-1960), I, pp.21-22; II, pp.10-14 (locating what he believes may be the dedicatee’s copy in Munich, Universitätsbibliothek der LMU, 8° Coll. 150. [link]).

18. Michael Erbe, “Georg von Logau” in Contemporaries of Erasmus: a biographical register of the Renaissance and Reformation (Toronto 1986), pp.338-339.

19. Lucii Petrei Zanchi Bergomatis, poemata varia. G. Logus S. (Vienna: Johann I Singriener, 1534; VD16 ZV 33630).

20. In laudem Catharinae Aquilae Augustanae Philippi filia, Georgii Loxani Silesii coniugis (Vienna: Johann I Singriener, ca 1534-1535; VD16 L 2349).

21. Epithalamivm de nvptiis magnifici et nobilissimi D. Georgij Loxani Regiae Maiestatis consiliarij (S.l., s.n., 1534; VD16 W 3535). In 1541, Logau dedicated to Loxau a collection of religious verse and epigrams (VD16 ZV 12238).

22. His examination was witnessed by Johannes Sinapius; see John Flood & David Shaw, Johannes Sinapius (1505-1560): Hellenist and physician in Germany and Italy (Geneva 1997), p.84.

23. Giuseppe Pardi, Titoli dottorali conferiti dallo studio di Ferrara nei sec. XV e XVI (Lucca 1900), p.128 [link]. Claudia A. Zonta, Schlesische Studenten an italienischen Universitäten: Eine prosopographische Studie zur frühneuzeitlichen Bildungsgeschichte (Cologne 2004), p.306.

24. Gerhard Zimmermann, Das Breslauer Domkapitel im Zeitalter der Reformation und Gegenreformation (1500-1600) (Weimar 1938), pp.375-377.

25. Hermann Kinne, Das Kollegiatstift St. Petri zu Bautzen von der Gründung bis 1569 (Germania Sacra, Dritte Folge 7, Das (Exemte) Bistum Meissen, 1) (Berlin 2014), pp.996-997.

26. Christian Schöttgen & G.C. Kreysig, Diplomataria et scriptores historiae Germanicae medii aevi, cum sigillis aeri incisis 2: De itineribus eruditorum virorum rei historicae fructuosis (Altenburg 1753-1760), II, p.38 no. LXI (“Ferdinandus etc. praesentat D. Georgium Logum ad praeposituram Ecclesiae Collegiatae S. Crucis Vratislauiae. Dattum Hagenoae 25. Maii 1540” [link]).

27. John Flood, Poets Laureate in the Holy Roman Empire (Berlin 2006-2019), pp.2419-2420.

28. Johannes Sinapius, Schlesischer Curiositäten … Vorstellung, Darinnen die ansehnlichen Geschlechter Des Schlesischen Adels (Leipzig 1720), p.609 [link].

29. The manuscript is now Vienna, Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Codex Historicus graecus 8; see Christian Gastgeber, Miscellanea Codicum Graecorum Vindobonensium II: Die griechischen Handschriften der Bibliotheca Corviniana in der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek: Provenienz und Rezeption im Wiener Griechischhumanismus des frühen 16. Jahrhundert (Vienna 2014), pp.291-306 (esp. pp.295-299). Suspicions about the story of its theft by the Ottomans and repurchase in Constantinople are raised by C. Gastgeber, “Die Kirchengeschichte des Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos. Ihre Entdeckung und Verwendung in der Zeit der Reformation” in Ostkirchliche Studien 58 (2009), pp.237-247 (pp.238-241).