Panel stamps used at Bologna, 1 - Rectangular plaques

The tools that binding finishers use to impress designs into the covering materials of books are of roughly three kinds, hand-held stamps and rolls (including fillets), and panels, which because they are larger require the assistance of a screw press. Bookbinders’ panel stamps are customarily made of metal, either engraved or cast from moulds, although as we shall see the earliest used at Bologna were probably cut in wood. Whenever possible, a pair of panels was employed, and both covers were decorated simultaneously, in a single operation. When they incorporate a complete design, and decorate most or all of one side of a binding, panels often are referred to as “plaques.”

This post is the first in a series of three providing details of panel-stamped bindings assumed to have been made at Bologna before about 1560. Presented here are bindings decorated by panels either rectangular in shape, or with the decoration contained within a rectangular frame. In a second post [link] bindings decorated by polylobed elliptical panels of arabesque ornament are described. A third post [link] lists some rectangular panels of arabesque ornament used by bookbinders at Rome.

fifteenth century

The earliest surviving panel used at Bologna is found on the binding (Fig. 1) of a commentary on the Decretales of Gregory IX by Francesco Zabarella, canonist and professor of law at Padua (1360-1417). The manuscript is dated 1408, and an inscription indicates that in 1411 it was taken to Padua by one “Dominus Johannes”.1 The covering material is a reddish-brown leather (calf or sheep), drawn over boards composed of sheets of paper pasted together. The large panel (400 x 280mm) is lettered with three pious inscriptions (in German), separated by bands of flowers.

Fig. 1. A panel used at Bologna ca 1410. The borders contain the words (repeated) “hilf got” - “wan got will” - “getreue kann dich selben”

The same panel is impressed on four volumes of commentaries on Justinian’s Digest of Roman civil law by Bartolo of Sassoferrato, in turn professor at Bologna, Pisa, and Perugia (1314-1357).2 Those manuscripts were written between about 1416 and 1419, by two scribes, Jodocus de Prucia and Johannes Erringer, both German students at Bologna. They were bought by a fellow student, Balthasar Ungerotin (Vngeroten) of Liegnitz (Silesia), who in 1420 was proclaimed doctor juris and returned with them to Wrocław (Breslau).3 The manuscripts are covered in either reddish brown or white leather, drawn again over pasteboards. This novel, technical feature attracted the attention of Anthony Hobson, who assigned all five bindings to Bologna, partly for the reason that manuscripts almost always were bound where they were written (unlike early printed books, ordinarily bound where they were sold). Hobson speculated that the binder was the beadle (bidellus) of the Natio Germanica Bononiae, who was often a stationer, and therefore also a binder.4

Fig. 2. A panel used at Bologna ca 1410-1430. The outer inscription reads “La lengua non [h]a osso ma la corpo et dosso” and in the centre is the single word “amore”

Fig. 3. Panels used at Bologna ca 1410-1430. The visible inscription on the upper cover is a version of the Latin proverb “Haurit aquam cribro, qui discere vult sine libro” (The person who wants to learn without a book is gathering water in a sieve)

Another binding, also in pasteboards, and covered with red leather, is impressed by a different panel (Fig. 2). It contains a theological miscellany (150 x 105mm), written and illuminated at Bologna about 1330.5 This panel follows a similar model, with two inscriptions (in Italian) separated by bands of foliage.6 A seventh binding (Fig. 3), its pasteboards covered by white leather (245 x 238mm), contains a manuscript of De universo spirituali by Guillaume d’Auvergne (1190-1249). Four vellum leaves from the discarded registry of a 13C Bolognese notary were used as endpapers (two at each end). Each cover is impressed with a different panel. On the upper cover are three scenes (a wild man, a wild woman, and Samson’s fight with the lion) enclosed by two inscriptions (in Latin), the outermost absent at top and bottom, as the panel was much too large for volume it decorates. On the lower cover are three roundels (identified by E.P. Goldschmidt as a dwarf, the Paschal Lamb, and a mermaid), again enclosed by two inscriptions (the outermost visible only at the sides).7 Hobson assigned these bindings also to Bologna, but was unsure whether they were bound in the shop of the German Nation, or elsewhere at the university.

sixteenth century

Pictorial panel stamps of the type commonly used in north-western Europe from the last quarter of the fifteenth century until about the middle of the sixteenth are almost non-existent in Italy. The few surviving Italian examples belonged to booksellers in Liguria and Piedmont, and their use was doubtless the result of French influence.8 Several panels of interlaced ornament, with openings to accommodate a plaquette (or a hand stamp), were used in Rome ca 1509-1525, either in gilt or blind.9 But by and large, Italian binders continued to decorate covers with hand tools, and rejected the northern labour-saving devices of the panel and the roll.

From the second quarter of the sixteenth century onwards, economic reasons caused binders in the three principal centres of fine binding in Italy - of which Bologna was one - to add panels to their kit of tools. While demand for books no doubt was the precipitating cause, a contributory factor may have been a new fashion for covers richly gilt with arabesque ornament. Such designs were very time-consuming and laborious to build-up using hand tools. The panel saved both time and labour and also gave a much better result.

Fig. 4. Details Left Vavassore, Opera noua uniuersal intitulata corona di racammi (Venice ca 1530) [link]

Centre Zoppino, Esemplario di lavori (Venice 1529) [link]

Right Master F (ca 1530) [link]

Arabesque (or more properly moresque) ornament had been introduced into Italy via Venice late in the fifteenth century and popularised in print series by the Master f (1520-1530) and anonymous printmakers, and in textile pattern books published there by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente (1527), Nicolò Zoppino (1529), Giovanni Andrea Vavassore (1530), Matteo Pagano (1532), among others. Characterised by interlaced vegetal tendrils with stylised leaves, often organised vertically around a central axis, and covering the entire surface, it was applied by craftsmen in the most diverse fields to objects of all kinds, but especially damascened metalwork, furnishing textiles, and bookbindings. Although the published patterns are mostly horizontal strips, ideal models for bookbinders, the Italian binders did not adopt them as templates (as occurred later in France),10 but drew on individual elements or structural principles.

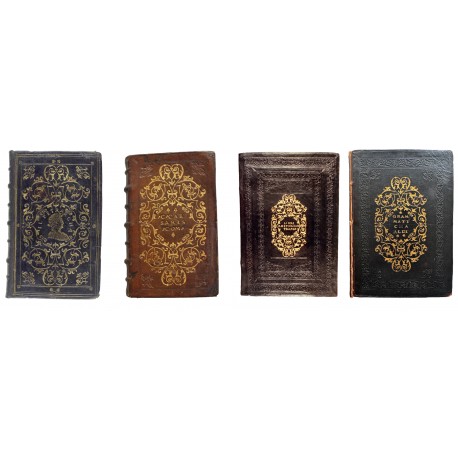

Arabesque ornament on Bolognese bookbindings: Type A (I-A/3, I-A/5, I-A/7, I-A/8 in List below)

Arabesque ornament on Bolognese bookbindings: Types B-C (I-B/2, I-B/6, I-B/7, I-C/1 in List below)

Arabesque ornament on Bolognese bookbindings: Type D (I-D/3, I-D/4, I-D/7, I-D/11 in List below)

Arabesque ornament on Bolognese bookbindings: Type E (I-E/1, I-E/3, I-E/4, I-E/5 in List below)

type a: the german students’ binder

It was customary for Germans attending the Italian universities at Padua and Bologna to commission bookbindings as mementos of their student years. Typically, the book’s title was displayed within a cartouche on one cover, and the owner’s name in an identical cartouche on the other. A Bolognese bindery active from about 1520 to 1535 which included German students among its clientele (hence designated “The ‘German Students’ Binder’” by Anthony Hobson) produced many such bindings. It employed a limited range of decorative patterns. Initially, its use of gilt arabesque ornament was modest, as for example on the shop’s bindings (Fig. 5a-b) for Jakob von Mosheim (matriculated 1522) and Dietrich (Theodor) von Spiegel (matriculated 1524), which are decorated mostly in blind with arabesque cornerpieces and borders formed by repeated arabesque hand tools, and in gilt by a triangular arabesque block placed at each end of a rectangular cartouche.11

Fig. 5. Bindings by the German Students’ Binder (a [link] b [link] c-d [link])

From about 1524, more elaborate gilt arabesque decoration is seen, as for example on bindings by the German Students’ Binder for V.C.A. (Pieter Van der Vorst?) dated 1524 and 1526 (Fig. 5c-d), and on bindings for the students Alessandro and Ranuccio Farnese (see Type I-A/5 and A/8 in List below). How the German Students’ Binder applied this decoration to the covers is an open question. Hobson declared that it was achieved from “a large plaque of arabesque ornament” and he listed four books printed between 1519 and 1527 in bindings by the German Students’ Binder on which it is featured (I-A/1-4).12 Two of those four bindings have been examined (I-A/3-4) and more examples found (I-A/5-9). Most covers bear traces of lines scored by the binder, in the form of a cross, to enable accurate positioning of a block. However, misaligned tools and an uneven distribution of pressure imply that the decoration on some bindings was executed using half-panel stamps or blocks, engraved or cast, repeated head to tail horizontally (tête-bêche), and applied on the covers by the use of a hammer or in a press. Available illustrations of other bindings, such as that made for V.C.A. in 1526 (I-A/7), suggest the application of a larger, full-panel stamp.

Fig. 6. Details from bindings by the German Students’ Binder (Top I-A/3 Middle I-A/5 Bottom I-A/8)

types b-c

The design evolved into a stock pattern, which endured until at least 1560 and is associated (by Hobson) with other Bolognese binderies and also with Roman shops. Hobson cites another four bindings on books printed 1515-1549 executed in anonymous Bolognese shops using what he calls a “two-part plaque” (see below, Type I-B/1-4),13 and a binding by “The ‘First S. Salvatore Binder’” covering a Venetian book of 1555 “stamped with a large plaque and lavishly, though roughly, gilt” (I-C/1).14

Judging from illustrations of the four bindings decorated by the “two-part plaque”, it appears that either a different stamp was used for each of the eight covers, or the decoration was built-up using blocks and individual hand tools. But without handling the four bindings, as Hobson presumably did, we hesitate to dispute his claim, and simply re-present his four bindings together with a few additional examples, as an aid for future investigations.

Details (top to bottom) from I-B/1, I-B/2, I-B/3, I-B/4 (upper cover, lower cover, upper cover)

type d: the pflug & ebeleben binder

The clientele of the German Students’ Binder and very probably also its equipment were taken over by a binder designated by Hobson the “Pflug & Ebeleben Binder” after its two important clients. Among the shop’s earliest work are three bindings for the student Georg Zollner von Brand, who was promoted doctor of civil and canon law at Bologna in 1535 and afterwards returned to Bamberg. Those bindings (images, [link]) are decorated in the traditional style with blind borders and cornerpieces enclosing a gilt cartouche formed of arabesque ornament.

From about 1540, the shop began producing bindings with gilt arabesque decoration of scrolls and stems and stylised leaves covering the entire surface. Hobson lists eleven bindings featuring “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” which he believed “was used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’” (see below, Type I-D/1-11).15 Hobson mentions an additional binding, “decorated with one of the ‘Students’ Binders’ favourite large plaques accompanied by ‘Pflug and Ebeleben’ tools” (Bologna, Archivio di Stato, Fondo Demaniale, Abbazia di SS. Naborre e Felice, 86/914), and he publishes without comment one covering a portolan atlas which also features the German Students’ Binders’ tools (Fig. 7).16

Fig. 7. Grazioso Benincasa, Atlante nautico (1473), bound ca 1550-1560 by the Pflug & Ebeleben Binder using materials of the German Students’ Binder

Hobson’s expressions “two-part plaque” and “one plaque in two parts” allude to Staffan Fogelmark’s revolutionary study, published in 1990, on the manufacture and use of panel stamps.17 Fogelmark demonstrates that binder’s panels were not engraved, but cast, and therefore were not unique objects, but multiples, identical except in the event of casting flaws. In order to press both covers in a single operation (by far the most economic procedure), binders required two stamps of a panel, hence Hobson’s “one plaque in two parts”. Binders with foresight would have commissioned extra stamps of the same design in anticipation of the damage (cracking) which occurred in daily work. A bindery operating several presses simultaneously might require multiple panels of the same design. If they could not be borrowed from colleagues, the process of “clichage” (re-casting) enabled the binder to create new generations of panels from those in his possession, potentially different from their sources. Thus, two stamps used to decorate the upper and lower boards of a single binding could easily have dissimilar origins. The covers would then exhibit subtle or even profound differences.

The eleven panel-stamped bindings which Hobson associates with the Pflug and Ebeleben Binder are of quite disparate design. His assertion that “one plaque in two parts” was used to decorate all of them is unconvincing, despite Fogelmark’s explanations of the variations produced by repeated clichage. The question once again arises: are some of these bindings decorated by blocks and hand tools, not by panels?

type e: the binder of ulrich fugger’s bible

Another Bolognese shop producing gilt bookbindings, known by its most celebrated production, the binding on a Latin Bible bound for Ulrich Fugger, also used arabesque plaques. Hobson supposed that it was situated near the Pflug and Ebeleben Binder, as the two binderies appear to have undertaken jointly the binding of a five-volume Aldine Aristotle, and frequently shared tools. Nevertheless, Hobson distinguished thirteen bindings as bound exclusively by “The Binder of Ulrich Fugger’s Bible” during the comparatively brief period of its activity, ca 1533 to ca 1550. Four bindings in that list are said to be decorated by plaques (E/1, E3-5).

types f-k: panels used by anonymous binders

Other types of arabesque panel stamps may be tentatively localised to Bologna by their use in combination with certain emblematic tools. Hobson linked to the Pflug and Ebeleben Binder tools of the Crucifixion (compare here I-D/3) and Madonna and Child (I-D/3, I-D/9, I-K/1), and associated with the Ulrich Fugger’s Bible Binder tools of a Cupid, usually blindfolded and shooting an arrow (I-D/13, I-D/14, I-F/1, I-I/1, I-I/2, I-I/3).18 Tools of a Roman Emperor (?) (I-B/4), the bust-portrait of a poet crowned with a laurel (I-A/3, I-A/4), Fortune on the back of a dolphin holding a billowing sail (I-D/4, I-F/1), the “clasped hands” symbol of faithfulness (I-D/5), a hand with finger pointing upwards to heaven (I-D/8), and the “vase of flames” symbol of love (I-H/1), are centred within the panel on other bindings. Variants of some tools are known, used without a panel stamp on bindings from different towns. For the moment, claims for a Bolognese origin of these bindings rest entirely on provenance.

1. Francesco Zabarella, Commentarium super IV et V libro Decretalium cum repetitione c. Perpendimus (Kraków, Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Rkp. 355 IV; opac, [link]). The first owner of the manuscript is unknown; it later was owned by the humanist Mikołaj Czepiel (ca 1453-1518).

2. Super prima parte Digesti novi (Kraków, Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Rkp. 335 III; opac, [link]); Lectura super prima parte Digesti Infortiati dictis Nicolai Spinelli de Neapoli aucta (Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Rkp. 336 IV; opac, [link]); Lectura super prima parte Digesti Veteris (Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Rkp. 338 IV; opac, [link]); Lectura super secunda parte Digesti Novi (Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Rkp. 340 IV; opac, [link]). Anna Lewicka-Kamińska, “Włoskie oprawy plakietowe z lat 20 XV wieku w Bibliotece Jagiellońskiej [Italian plaque bindings from the 1420s in the Jagiellonian Library; summary in French]” in Biuletyn Biblioteki Jagiellońskiej 24-25 (1975), pp.81-89.

3. Gustav Knod, Deutsche Studenten in Bologna (1289-1562) (Berlin 1899), p.589 no. 3930 ([link]; cf. nos. 2871, 836 for the two scribes); Repertorium Academicorum Germanicorum (rag), [link].

4. A. Hobson, Humanists and bookbinders: the origins and diffusion of the humanistic bookbinding 1459-1559 (Cambridge 1989), Appendix 1: The use of pasteboard in binding (p.253); A. Hobson, “Bookbinding in Bologna” in Schede umanistiche, n.s., 1 (1998), pp.147-175 (p.149); A. Hobson & Leonardo Quaquarelli, Legature bolognesi del Rinascimento (Bologna [1998]), p.10; A. Hobson, “Some early pasteboard bindings - Bologna, Silesia or Kraków” in Association international de Bibliophilie, Actes et communications, Pologne, XXVIIe congrès [2011] ([Czech Republic?] 2017), pp.77-91 (pp.83-84). Hobson suggests that this large panel was “possibly made of wood” (p.80).

5. Ps.-Augustinus, Bernardus Claraevallensis, Thomas de Aquino, etc (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 675; opac, [link], digitised, [link]). It belonged to Giovanni Gaspare da Sala (ca 1440-1511), who may have inherited it from his father, Bornio da Sala (d. 1469), a jurist at Bologna’s university. Ernst Kyriss, “Zwei unbekannte Plattenstempel aus gotischer Zeit” in Gutenberg Jahrbuch 1955, pp.249-253.

6. The outer inscription “La lengua non [h]a osso ma la corpo et dosso” incorporates a meaningless letter “n” between “la” and “corpo,” leading Hobson to suppose that the binder was an alien, perhaps the beadle of the German Nation in Bologna (op. cit. 2017, pp.81, 84).

7. Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, Ms Add. 6171. E.P. Goldschmidt, “An Italian panel-stamped binding of the fifteenth century” in Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 1 (1949), pp.37-40. Goldschmidt considered that the two panels “must have been metal plates engraved to some depth” (p.37).

8. Francesco Malaguzzi, “Legature del Cinquecento decorate con piastre e placchette nella Biblioteca comunale dell’Archiginnasio” in L’Archiginnasio 90 (1995), pp.23-31; F. Malaguzzi, “Rare legature con piastre e plaquette in biblioteche del Piemonte” in Bulletin du Bibliophile (2005), pp.351-362; Anthony Hobson, “Panel-Stamps used on Italian Bindings” in Comites latentes per gli ottanta anni di Francesco Malaguzzi (Vercelli 2010), pp.49-70.

9. Hobson, op. cit. 1989, p.218 (8c), p.221 (15k, 15l [image]); A. Hobson, “Plaquette and medallion bindings: A supplement” in Bulletin du bibliophile (1994) pp.24-37 (p.75, no. 15lx). A different panel covering a copy of Francesco Cei, Sonecti, capituli, canzone, sextine, stanze et strambocti (Florence: Filippo Giunta, 1503) is cited by Hobson, op. cit. 1989, p.221, no. 15m (Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: The Aldine Collection A-C, New York, 12 October 2023, lot 263 [link; image]. A panel with three circular openings on a copy of the 1505 Aldine Pontani Opera in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (opac, [link]) is described by Hobson, “Plaquette and medallion bindings: A supplement” in Bulletin du bibliophile (1994) pp.24-37 (p.25, no. 15mm).

10. Fabienne Le Bars, “Maurusias & Co.: the influence of Hieronymus Cock’s print series on bookbinding in sixteenth-century Paris” in Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 39 (2017), pp.197-214.

11. Compare De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, nos. 1273, 1279 & Pl. 221 (two bindings for Christoph Schlick, a student in Bologna 1523-1526).

12. Hobson, op. cit. 1998, pp.157-158; Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.17.

13. Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174; Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, pp.29-30.

14. Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.165; Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.22.

15. Hobson, op. cit. 1998, pp.173-174; Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29.

16. Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.166; Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.23 and no. 40.

17. Staffan Fogelmark, Flemish and related panel-stamped bindings: evidence and principles (New York 1990).

18. Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174; Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.30.

type a: german students’ binder

(I-A/1) Gaius Iulius Caesar, Hoc volumine continentur haec. Commentariorum de bello Gallico libri VIII (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, [January 1518] November 1519)

provenance

● Budapest, Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Ant. 445 (opac (translation:) Contemporary Italian Renaissance brown leather binding, boards decorated with gilded plates with arabesque patterns, gilded inscription in the middle: ‘C. Ivlii Caesaris Commentaria’, on the back board: ‘Non semper idem’ [link])

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.158 [as decorated by a large plaque of arabesque ornament used by “The ‘German Students’ Binder’”]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.17

(I-A/2) Marcus Tullius Cicero, In hoc volumine haec continentur. M. T. Cic. Officiorum lib. III. (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, February 1519)

provenance

● Chatsworth, Devonshire Collections Archives & Library

literature

J.P. Lacaita, Catalogue of the library at Chatsworth, Volume I A-C (London 1879), p.382 [link]

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.158 [as decorated by a large plaque of arabesque ornament used by “The ‘German Students’ Binder’”]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.17

(I-A/3) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarcha (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, July 1521)

provenance

● London, British Library, C.65.d.14

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.158 [as decorated by a large plaque of arabesque ornament used by “The ‘German Students’ Binder’”]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.17

(I-A/4) Priscianus Caesariensis, Prisciani grammatici Caesariensis Libri omnes. De octo partibus orationis XVI: deque earundem constructione II. De duodecim primis Aneidos librorum carminibus. De accentibus. De ponderibus, et mensuris. De praeexercitamentis rhetoricae ex Hermogene. De versibus comicis. Rufini item de metris comicis, et oratorijs numeris (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, May 1527)

provenance

● unidentified owner(s), inscription dated 1544 or 1548 on title-page (washed), contemporary marginalia

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982), exlibris

● Ader Picard Tajan & Claude Guérin with Dominique Courvoisier, Incunables et livres anciens provenant de la Fondation Furstenberg-Beaumesnil, Paris, 16 November 1983, lot 156 (“Reliure représentative des productions des ateliers de Venise à cette époque. Ce portrait, représentant un poète romain, la tête décorée d'une couronne de lauriers est reproduite par de Marinis (1779, pl. [339]”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 4500)

● possibly Martin Breslauer Inc., New York

● Christie Manson & Woods, Valuable printed books and manuscripts, London, 13 December 1984, lot 90

● Alan G. Thomas, London - bought in sale (£550)

● Purchased from Alan G. Thomas, London, 1985

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased from the above, 1985 [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0350]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection: N-Z, New York, 25 June 2025, lot 1364 ($3810) [RBH N11571-1364]

literature

Exposition de reliures de la Renaissance: collection Jean Furstenberg: 30 September 1961 (Paris 1961), no. 92

Musée d'art et d'histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 51

De Marinis, op. cit. 1966, pp.134-135

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.158 [as decorated by a large plaque of arabesque ornament used by “The ‘German Students’ Binder’”]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.17

(I-A/5) Julius Caesar, Hoc volvmine continentvr haec. Commentariorum de bello Gallico libri VIII. De bello ciuili Pompeiano. Libri IIII. De bello Alexandrino. Liber I. De bello Africano. Liber I. De bello Hispaniensi. Liber I (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, (January 1518) November 1519)

provenance

● Ranuccio Farnese (1530-1565; created cardinal deacon 16 December 1545), supralibros “Ranvtii Farnesii”

● unidentified owner(s), initials “AE” in ink on upper cover, annotations

● Edward Worth (1676-1733

● Dublin, Dr. Steevens’ Hospital, Edward Worth Library, 3257 (opac “Bound in early to 16th c Italian blind- and gold-tooled brown goat with blind-tooled triple fillet frame intersecting at the corners and with triple fillets leading to the edges from the corners; blind-tooled floral corner tool in angles; gold-tooled arabesque panel stamp with central lettering: ‘C. Caesaris Com’ on the front cover and ‘Ranvtii Farnesii’ on the back cover; spine gold-tooled with single fillets on either side of seven false bands (sewn on three), plus blind-tooled double fillets; gold ‘epigraphic ivy leaf’ tool at head and tail of spine; edges stained in blue; endbands in blue and plain; white paper pastedown attached to one white leaf; sewn on three alum-tawed thongs; ‘A E’ written at top of front cover in ink” [images, link])

(I-A/6) Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. Tullii Ciceronis Epistolae ad Atticum, ad M. Brutum, ad Quinctum fratrem, cum correctionibus Pauli Manutii (Venice: Paolo Manuzio, 1558 [1559])

provenance

● Guido Sforza, supralibros, lower cover lettered “Gvidi Sfortiae”

● Arthur Lauria, Paris

● Maurice Burrus (1882-1959), purchased from the above in 1937

● Christie’s, Maurice Burrus (1882-1959): la bibliothèque d'un homme de goût: Première partie, Paris, 15 December 2015, lot 42 (“Reliure bolognaise du milieu du XVIe siècle. Bologne est la seule ville en Italie qui ait utilisé très largement pendant la Renaissance des plaques pour le décor des reliures (Hobson-Quaquarelli, p.98, n.46)”)

(I-A/7) Georgius Trapezuntius, Continentur hoc volumine. Georgii Trapezuntii Rhetoricorum libri V. Consulti Chirii Fortunatiani libri III. Aquilae Romani de figuris sententiarum, & elocutionis liber. P. Rutilii Lupi earundem figurarum e Gorgia liber. Artistotelis rhetoricorum ad Theodecten Georgio Trapezuntio interprete libri III. Eiusdem rhetorices ad Alexandrum a Francisco Philelpho in Latinum uersae liber. Paraphrasis rhetoricae Hermogenis ex Hilarionis monachi Veronensis traductione. Priscianus de rhetoricae praeexercitamentis ex Hermogene. Aphthonii declamatoris rhetorica progymnasmata Io. Maria Catanaeo tralatore [Latin and Greek] (Venice: Heirs of Aldus Manutius & Andreas Torresanus, April 1523)

provenance

● possibly Pieter Van der Vorst, supralibros, lower cover lettered: ANNO | M.D. XXVI | .V.C.A.

● unidentified owner, contemporary marginalia

● Collegio dei Gesuiti, Viterbo, inscription “Coll. Viter(bo) Soc. Jesu. Cat. Inscr.” on title-page [founded 1622, suppressed 1868]

● Louis Eugène Jean Birkigt (b. 1903)

● Librarie André Cottet, Manuscrits, incunables, XVIe-XIXe siècle riches reliures, Geneva, 10 November 1967, lot 76

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (CHF 4200)

● Martin Breslauer, Inc., New York

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased from the above, 1977 [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0325]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection: D-M, New York, 18 October 2024, lot 748

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.157 [as bound by the German Students’ Binder]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.17

(I-A/8) Aldo Manuzio, Aldi Pii Manutii Institutionum grammaticarum libri quatuor. Erasmi Roterodami Opusculum de octo orationis partium constructione (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, July 1523)

provenance

● Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589; appointed Cardinal 18 December 1534), supralibros, lettered “Alex. Farnesii” on lower cover

● Archibald Acheson, 3rd Earl of Gosford (1806-1864)

● James Toovey, London

● New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, 001443 (opac, [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1347

Howard Nixon, Sixteenth-century gold-tooled bookbindings in the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York 1971), p.94 (“It has a gilt block used in the centre of the covers, which closely resembles the designs on some of the Ebeleben bindings, with a blind tooled border and corner tools. But the design of the block is not enough to make this a Bologna binding.”)

Paul Needham, Twelve centuries of bookbindings, 400-1600 (New York 1979), p.154 (“A rather primitive-looking Italian arabesque panel impressed in gilt”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.158 [as bound by the German Students’ Binder]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.18

(I-A/9) Theodorus Gaza, Introductivae grammatices libri quatuor (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, 1495)

provenance

● possibly Pieter Van der Vorst, supralibros, lower cover lettered: .V.C.A. | ANNO DNI | .M.D. XXIIII | XXXI AV | GV.

● Sebastianus Miegius (d. 1609), inscription “Ex bibliotheca Sebastianj Miegij ad Andream Norrelium, fatis ita ducentibus, anno Christiano MDCCIII die xxiii octobris tandem penetravit” (Collijn)

● Andreas Norrelius (d. 1749) [librarian at Upsala, 1735; Collijn p.44]

● Lars Benzelstjerna, Bishop of Västerås 1759-1800 (Collijn p.42)

● Västerås, Stads och Landsbiblioteket, Ink. 54 (libris (Swedish union catalogue) “V. C. A. ANNO DNI .M. D. XXIIII XXXI AVGV. (printed on lower cover). Ex bibliotheca Sebastianj Miegij ad Andream Norrelium, fatis ita ducentibus, anno Christiano [M] DCCIII die XXIII octobris tandem penetravit. Donation Benzelstjerna 1809. Gilt tooled black leather binding” [link])

literature

Isak Gustaf Alfred Collijn, Kataloge der inkunabeln der schwedischen öffentlichen bibliotheken. 1, Katalog öfver Västerås läroverksbiblioteks inkunabler (Upsala 1904), p.19 no. 54 (“Sv. sk.-bd m. guldtr. på bakre pärmen: V. C. A. ANNO DNI .M. D. XXIIII XXXI AVGV” [link])

Anthony Hobson, Humanists and bookbinders: the origins and diffusion of the humanistic bookbinding, 1459-1559 (Cambridge 1989), p.164 (“no doubt a northern student”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.157 [as bound by the German Students’ Binder]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.17

type b: anonymous bolognese shops

(I-B/1) Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. T. Ciceronis Orationum volumen tertium (Venice: Heirs of Aldus Manutius & Andreas Torresanus, August 1519)

provenance

● Gerhard Aich, supralibros, monogram vADRI (Aich Dr utriusque iuris)

● Effisio Paoletti (1784-1849), inscriptions “E. Effisio Paoletti di Recanatti” and “E. Effisio Paoletti Roma” on lower endleaf

● Renzo Salvadè (d. 2018)

● Libreria Docet, Bologna

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 2010) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0265; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection, A–C, New York, 12 October 2023, lot 311, unsold at estimate $6000-$8000, link, RBH N11294-311; sold January 2026 to]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174 [as bound in an anonymous shop using a “two-part plaque”]

Hobson & Leonardo Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, no. 46 (illustrated)

(I-B/2) Antonio Cornazzano, De re militari (Florence: Heirs of Filippo Giunta, 15 May 1520)

provenance

● Marcantonio Totila (fl. 1527-1550), supralibros

● Bologna, Biblioteca universitaria, Raro B. 59 (digitised catalogue, [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1351bis

Hobson op. cit. 1998, p.174 [as bound in an anonymous shop using a “two-part plaque”] & Fig. 15 (lower cover illustrated)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, no. 45 (lower cover illustrated)

Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Catalogo online delle legature storiche (“Cuoio di capra marrone su quadranti in cartone decorato a secco e in oro. Decoro del genere orientaleggiante realizzato tramite l’impressione a placca; al centro del piatto anteriore il cognome dell’autore e il titolo dell’opera, e il destinatario Marcantonio Totila a quello posteriore” [link])

(I-B/3) Antonio de Guevara, Auiso de fauoriti e dottrina de cortegiani, con la commendatione della uilla, opera non meno utile che diletteuole. Tradotta nuouamente di spagnolo in italiano per Vincenzo Bondi Mantuano (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1549)

provenance

● unidentified owner, armorial supralibros, insignia flanked by the initials B.M., probably a member of the Magnani family of Bologna

● unidentified owner(s), occasional marginalia, one compartment with shelfmark inked “433” in a 17th-century hand

● Giovanni Gancia, Brighton & Paris

● Delbergue-Cormont & Librairie Bachelin-Deflorenne, Catalogue de la bibliothèque de M. G. Gancia composée en partie de livres de la première bibliothèque du Cardinal Mazarin et d’ouvrages précieux, Paris, 27 April-2 May 1868, lot 245 (“mar. br., riches compart. en or, tr. dor. et ciselée. Exemplaire de Matteo Bandello, avec ses armoiries et initiales B.M. au milieu des plats. Riche reliure vénitienne de l’époque, d'un dessin parfait” [link])

● unidentified owner, exlibris, initials “G.E.” (19-20C)

● unidentified owner, red oval inkstamp “642”

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a collection of valuable & rare books and important ancient illuminated and other manuscripts, London, 12-14 April 1899, lot 315 (“contemporary Venetian brown morocco, floreate ornaments on back, rich and elegant scroll ornaments on sides, shield of arms in centres, with initials B.M. gilt and gauffered edges (well preserved)”)

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£6 5s) [Book Prices Current, 13, no. 4788]

● Maggs Bros, London; their Catalogue 830: Printing, illustration, binding & illumination: a classified catalogue of books and manuscripts XIVth to XIXth centuries (London 1956), item 64 & Pl. VIII (£40) [RBH 830-64]

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982), exlibris

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York; their Catalogue 104/II: Fine books in fine bindings from the fourteenth to the present century (New York 1981), item 169 ($4500; “two slightly varying panels, one used for the upper, the other for the lower cover, the latter also being employed on a well-known Cicero bound for a German student at Bologna, Gerhard Aich, in the Victoria and Albert Museum”); Catalogue 107: Italy, Part II: Books printed 1501 to c. 1840 (New York [1984]), item 63; Catalogue 110: Fine books and manuscripts in fine bindings from the fifteenth to the present century followed by literature on bookbindings (New York 1992), item 39 ($6800)

● Otto Schäfer (1912-2000), acquired in 1992 (OS 1532)

● Otto-Schäfer-Stiftung e.V., Schweinfurt

● Sotheby’s, The collection of Otto Schäfer. Part I: Italian books, sold by order of the Dr. Otto-Schafer-Stiftung e.V., New York, 8 December 1994, lot 87 [RBH 6649-87]

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased at the above sale via Martin Breslauer Inc. [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #2216]

● Sotheby's, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part VII, London, 11 July 2025, lot 1721 (£7620) [link]

literature

Exposition de reliures de la Renaissance: collection Jean Furstenberg: 30 September 1961 (Paris 1961), no. 56 (“Reliure vénetienne”)

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 40

De Marinis, op. cit. 1966, pp.112-113

Manfred von Arnim, Europaïsche Einbandkunst aus sechs Jahrhunderten: Beispiele aus der Bibliothek Otto Schäfer (Schweinfurt 1992), no. 34

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174 [as bound in an anonymous shop using a “two-part plaque”]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-B/4) Titus Lucretius Carus, Lucretius (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, January 1515)

provenance

● Christie’s Roma, Libri di pregio, manoscritti e autografi da collezioni private, Rome, 10 June 1997, lot 95 (“magnifica legatura bolognese coeva di marocchino marrone riccamente impressa a freddo, al centro del piatto superiore stampato in oro ‘Lucretius’ sul piatto inferiore un busto di un imperatore romano, qualche leggerissimo danno” [link])

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174 [as bound in an anonymous shop using a “two-part plaque”]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-B/5) Aeschylus, Aeschyli Tragoediae sex [title also in Greek] (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, February 1518), bound with Musaeus Grammaticus, Musaei opusculum de Herone & Leandro. Orphei argonautica. Eiusdem hymni. Orpheus de lapidibus [title also in Greek] (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, November 1517)

provenance

● Arthur Atherley (1772-1844), exlibris

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a choice selected portion of the famous library removed from Sudbury Hall, Derbyshire: including illuminated and other manuscripts, and rare printed books, London, 10-12 June 1918, lot 5 (“XVIth cent. Lyonese binding of brown morocco, sides covered with gilt scrolls and arabesques, g.e. (repaired)” [link])

● P.J. & A.E. Dobell, London - bought in sale (£7)

● Goodspeed's Book Shop, Boston

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased from the above, 1991 [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0258]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: a Renaissance Library. The Aldine Collection A-C, New York, 12 October 2023, lot 102 [link]

● unidentified owner- bought in sale ($10,160) [RBH N11294-102]

literature

presumably the copy listed in “A catalogue of the library at Sudbury Hall, Derbyshire” (ca 1836-1840?) [Vernon’s Ms catalogue, in Grolier Club Library; qv Aeschylus 1518, morocco binding, with a pencil tick indicating its sale to Holford]

(I-B/6) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Orationum volumen primum (Venice: Heirs of Aldus Manutius & Andreas Torresanus, January 1519)

provenance

● Gerhard Aich, supralibros, monogram vADRI (Aich Dr utriusque iuris)

● unidentified owner, inscription at top of title page “XXVII”

● unidentified owner, inscription “Antonij Pacij F” on folio *2 recto

● Baccio Bandinelli, gift inscription on title-page to the Florentine Accademia degli spensierati of which he was a member: “Baccio Bandinelli Riecercatto [academic name of Bandinelli?] Accademico Spensierato Don Questo Libro Alla Accademia delli Spensierati Questo Di 11 di Aprile 1603”

● Hieronimus Gratius Persusinus, two inscriptions (one dated 1696)

● Libreria antiquaria Arrigoni Luigi, Corso Venezia, Milan, printed label

● Victoria & Albert Museum, London, acquisition date stamp “22.3.82 | 285”

● London, National Art Library, Drawer 51

literature

William Henry Weale, Bookbindings and rubbings of bookbindings in the National Art Library, South Kensington. 2: Catalogue (London 1894), p.57 no. 239 (Art Libr., 285-1882)

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1315 & Pl. 224

(I-B/7) Christophe de Longueil, Christophori Longolii Lucubrationes. Orationes III. Epistolarum libri IIII (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1542)

provenance

● Biblioteca del convento di S. Teresa, Piacenza

● Piacenza, Biblioteca Comunale Passerini-Landi, (L) L/3.02.011 (opac Sulla coperta titolo in oro)

literature

Catalogo delle legature storiche di pregio della Biblioteca comunale Passerini-Landi, Parte seconda, no. 306 (“Legatura del secondo quarto del secolo XVI, verosimilmente eseguita a Roma, del genere “a placca” … Nella cartella centrale, campeggia la scritta orat | iones | lo | ngolii sul piatto anteriore, a | de | v su quello posteriore con una sottostante scritta parzialmente cancellata. … Legatura decorata a placca, realizzata con una medesima matrice, utilizzata su coperte rinascimentali realizzate a Bologna e a Roma; i gigli lungo il dorso tuttavia, orientano tuttavia maggiormente verso un’origine romana.” [link])

(I-B/8) Francesco Petrarca, Li sonetti, canzoni, et triomphi di m. Francesco Petrarcha historiati. Nuouamente reuisti, & alla sua integrità ridotti (Venice: Francesco Bindoni & Maffeo Pasini for Agostino Bindoni, 1542)

provenance

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Libreria antiquaria Ulrico Hoepli, Manoscritti, incunabuli, legature, libri figurati dei secoli XVI e XVIII. Terza parte della collezione De Marinis, Milan, 17-19 June 1926, lot 267 (“Bella legatura veneziana di marrocchino marrone; sul piatto anteriore, entro un graziosa decorazione d’arabeschi e fogliami, il motto Reliqvm habvisti; nel posteriore, entro la stessa decorazione, un braciere ardente e le lettere F. R. A., tagli dorati e cesellati”)

type c: first s. salvatore binder

(I-C/1) Roberto Caracciolo, Specchio della fede christiana volgare. Nouamente ristampato et con diligenza corretto et historiato (Venice: Bartolomeo Imperatore & Francesco Imperatore, for Pietro Nicolini da Sabbio, 1555)

provenance

● suor Maria Ludovica Fiorini

● Bologna, Biblioteca comunale di Bologna all’Archiginnasio, 16.f.IV.20

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1289H

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.165 [attributed to “The ‘First S. Salvatore Binder’. c. 1525-55”; “stamped with a large plaque and lavishly, though roughly, gilt”]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.22

Federico Macchi, Legature storiche dell’Archiginnasio (“Cuoio di bazzana marrone su cartone decorato a secco e in oro. Filetti concentrici. Cornice caratterizzata da urne alternate a fogliami. Tracce di quattro coppie di lacci in tessuto bruno. Specchio decorato a placca di foggia orientaleggiante. ... Il decoro della cornice e le note tipografiche inducono ad assegnare la legatura pubblicata al terzo quarto del XVI secolo, eseguita a Bologna dal primo legatore di S. Salvatore.” [link, link])

Federico Macchi, A fior di pelle: Legature bolognesi in Archiginnasio (second edition, Bologna 1999), p.27 no. 21

type d: pflug and ebeleben binder

(I-D/1) [Manuscript, Libro per farsi bella (Ricettario di bellezza)] Incominca il libro dei segreti galanti et prima il trattato per fare diverse acque perfette (mid-16C)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, motto “Di Buon Seme Mal Frutto” on both covers (Petrarca, Canzone in Morte de M. Laura, VII. 108)

● Giovanni Giacomo Amidei (d. 1768), inscription (in the hand of the librarian, Lodovico Montefani Caprara) “Ex bibliotheca Io. Iacobi Amadei Bononien. Canonici S. Mariae Majoris,” his bequest to Biblioteca dell’Istituto delle Scienze, Bologna

● Bologna, Biblioteca Universitaria, Ms 1352

literature

Ricettario galante del principio del secolo XVI, edited by Olindo Guerrini (Bologna 1883), p.iii (“Magnificamente legato in pelle, con dorature a ferri staccati nell’esterno dei cartoni, ha da ambe le parti una impresa che porta un mostro, un serpente colle gambe, un basilisco in atto di mordere una pianta che pare d’alloro. Intorno al fondo di stelle d’oro è impresso il motto di bon seme mal frvtto.” [link])

Mostra storica della legatura artistica in Palazzo Pitti (Florence 1922), no. 462 (“Mar. marrone coperto di fregi dorati a piccoli ferri a fondo pieno. Al centro, in un circolo, una salamandra in un paesaggio seminato di stelle, con l’iscrizione intorno: Di Bvon Seme Mal Frvtto, Dorso ornato e dorato: taglio dorato. (R. Bibl, Universitaria, Bologna)” [link])

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1320 & Pl. 227

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.173 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.96 no. 44 (“Marocchino verde oliva su cartone. Impressioni in oro … Legato dal Legatore di Pflug ed Ebeleben ca. 1550, per un possessore con il motto: ‘Di Buon Seme Mal Frutto’, con la stessa placca in due parti del n. 43” [Paolo Manuzio, Lettere volgari di diversi eccellentissimi huomini; see C/7 below])

Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Catalogo online delle legature storiche [link]

(I-D/2) Lodovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso dirigido al principe Don Philipe nuestro Señor, traduzido en romance castellano por don Ieronymo de Vrrea (Lyon: Guillaume Rouille, 1550)

provenance

● Thomas Grenville (1755-1846)

● London, British Library, G11108

literature

Mirjam Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: A collection of bookbindings, I: Studies in the history of bookbinding (London 1978), p.307 (“Bindings from the Pflug and Ebeleben bindery, not mentioned in the text,” no. 16)

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/3) Canonici Regulares Ordinis Sancti Augustini, Calendarium, regula, constitutiones, et ordinarium Canonicorum regularium Congregationis sancti Salvatoris Ordinis sancti Augustini (Rome: Antonio Blado, January 1549)

provenance

● Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Mscr.Dresd.g.125 (opac, [link]; Fotothek, [link])

literature

Ilse Schunke, “Die bibliophile Mission des Nikolaus Ebeleben” in Imprimatur 11 (1952-1953), pp.150-161 & Abb. 3

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1376

Foot, op. cit. 1978, p.307 no. 15

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/4) Luigi Cassola, Madrigali del magnifico signor cauallier Luigi Cassola piacentino (Venice: Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari, 1545)

provenance

● Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a further portion of the valuable library collected by the late Charles Fairfax Murray, London, 17-20 July 1922, lot 232 (“calf, the sides of a contemporary Italian binding very neatly laid on; dark olive morocco, arabesque tooling on sides, with central figure of Fortune, a naked woman holding a sail standing on a dolphin, at the four corners boys’ heads symbolical of the four winds, g. e.” [link])

● Joseph Baer & Co., Frankfurt am Main - bought in sale (£1 15s); their Catalogue 690: Bucheinbände: Bookbindings, historical and decorative: Livres dans de riches reliures (Frankfurt am Main [1927]), item 287 & Pl. 36

● New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, 22096 (opac “Contemporary Italian (Venetian) gold-tooled brown morocco. In the center panel is the standing figure of Fortune, holding a sail, with both hands” [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1394ter

Hobson, op. cit. 1989, p.164 Fig. 130

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.173 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/5) Baldassare Castiglione, Il cortegiano del conte Baldessar Castiglione (Venice: Gabriel Giolito de Ferrari, 1546)

provenance

● unidentified owner, using mottos “Qual sempre fvi tal esser voglio” (upper cover) and “Fede se[m]p[re] servai” (lower cover)

● unidentified owners, illegible inscriptions “[...] fuit P. Arcangelo Fen[...]anij fratris" e "Bernardo A[...]ndi 1591 Galentino [?]” [opac]

● Marcantonio V Borghese, principe di Sulmona (1814-1886), “Ex libris M.A. Principis Burghesii” [opac]

● Vincenzo Menozzi, Catalogue de la bibliothèque de S.E.D. Paolo Borghese, Prince de Sulmona, Première partie, Rome, 16 May-17 June 1892, lot 4508 (“in-8, maroq. rouge foncé, plats richement ornés, tr. dor. (rel. anc.) Très belle reliure vénitienne, style Grolier, que nous reproduisons presque à la moitié de la grandeur naturelle (p.525)” [link; image, link])

● Libreria Antiquaria Rappaport, Rome

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.123 (opac “Legatura in cuoio “alla Grolier”. Piatti decorati con fregi fitomorfi dorati. Nello specchio, due incisioni qual sempre fvi tal esser voglio e fede se[m]p[re] servai. Dorso a 3 nervi. Quattro fori per legacci. Taglio goffrato e dorato.” [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1330 & Pl. 228

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.173 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/6) Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, Lucanus (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, April 1502)

provenance

● Ulrich Fugger (1526-1584)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Membr.V.6 (opac “Legatura in pelle su piatti di cartone decorati con cornici ed elementi ornamentali impressi in oro. - Sul piatto anteriore, impresso in oro ‘lvcanvs bono m.d.xliiii’. - Sul piatto posteriore, impresso in oro ‘hvldrichvs fvggervs’. - Tagli goffrati in oro. - Tracce di quattro legacci. - Sul risguardo anteriore frammenti dell’antica legatura” [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1306

Ilse Schunke, Die Einbände der Palatina in der Vatikanischen Bibliothek (Città del Vaticano 1962), I, p.170 & Pl. 134; II, p.803

Ilse Schunke, “Die Renaissanceeinbandkunst in Bologna” in Beiträge zur Geschichte des Buches und seiner Funktion in der Gesellschaft. Festschrift für Hans Widmann zum 65. Geburtstag (Stuttgart 1974), pp.252-268 (pp.265-266)

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.173 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/7) Paolo Manuzio, Lettere volgari di diversi eccellentissimi huomini, in diverse materie. Libro secondo (Venice: Sons of Aldus Manutius, 1545), bound with Antonio de Guevara, Libro primo delle lettere (Venice: Bernardino Bindoni, 1545)

provenance

● Marcantonio Totila (fl. 1527-1550), supralibros, lettered: ma | rco | anto. | toti | la on lower cover

● Filippo Saverio Fanelli (fl. 1764-1771), inscription on first leaf of text “ex bibliotheca Philippi Xaverii Fanilli J.C. Florentini” (Filippo Saverio Fanelli Giureconsulto Fiorentino)

● Renzo Salvadè (d. 2018)

● Libreria Docet, Bologna

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 2010) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0462; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library. The Aldine Collection, D-M, London, 18 October 2024, lot 934, unsold against estimate $7000-$10,000, link; sold January 2026 to]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.173 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”) & Fig. 14 (lower cover illustrated)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, no. 43 (“La placca è in due parti, anteriore e posteriore, come appare dal confronto con il n. 44 [Ms Libro per farsi bella; see below] … Legato dal legatore di Pflug ed Ebeleben per Marcantonio Totila”)

(I-D/8) Officium Romanum, Officium ordinarium b. Mariae Virginis (Venice: Bernardino Stagnino, 15 December 1511)

provenance

● James Boswell, 2nd Baronet Boswell of Auchinleck (1806-1857)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the selected portion of the celebrated Auchinleck Library, formed by the late Lord Auchinleck, the property of Mrs. Mounsey, London, 23-26 June 1893, lot 531 (“printed in red and black, large woodcuts and borders to each page, on vellum, old calf, elaborately gilt on sides and back (restored)” [link])

● J. & J. Leighton - bought in sale for Sandars (£25 10s)

● Samuel Sandars (1837-1894), bequeathed 1894

● Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, SSS.18.4 (opac sixteenth-century gold-tooled boards (scrolling acanthus leaves and a finger pointing upwards to the centre of both boards). Rebacked and the original boards laid into the nineteenth-century binding. On vellum. [link]) CNCE 55756, no copy yet found in Italy]

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.173 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/9) Ordo fratrum praedicatorum, Processionarium secundum Ordinem fratrum predicatorum, quod secundo reuisum est literis & cantu quam diligentissime (Venice: Heirs of Lucantonio Giunta, 1560)

provenance

● Livia Zanon, supralibros, upper cover lettered “Svora Livia Zanona”

● unidentified bishop of Comacchio [“Antichi ex-libris del Vescovo di Comacchio” Philobiblon]

● Libreria antiquaria Hoepli, Manoscritti, miniature, incunabuli, legature, libri figurati dei secoli XVI e XVIII, Milan, 7-9 April 1927, lot 225 & Pl. 47 (“Legatura veneziana dell’epoca, assicelle di legno ricoperte di marrocchino marrone; piatti ornati con un ricco ed elegante intreccio d’arabeschi impressi in oro. Nel centro del piatto anteriore una graziosa effigie della Madonna col Bambino e circondata da sei stelline; nel centro del piatto posteriore il nome della proprietaria: Svora Livia Zanona. Dorso a nervi e piccoli ferri. Il piatto anteriore riparato agli angoli, dorso riparato.”)

● Carlo Alberto Chiesa, Milan [De Marinis]

● Fiammetta Soave, Rome

● Philobiblon, Rome; their Mille anni di bibliofilia dal X al XX secolo: Addenda (Rome [2008?]), item 15 (“Legatura parlante coeva in marocchino marrone, eseguita a Roma da Nicolò Franzese e riccamente decorata in oro. Il piatto anteriore presenta una riquadratura formata da una larga cornice di filetti e ferri di tipo aldino. Il campo centrale è quasi completamente coperto da ferri di tipo aldino a volute piene in cui si nota il fiore di arum con la classica spirale di Nicolò Franzese, al centro dello stesso, l’immagine della Madonna con il Bambino su di un crescente circondata da 6 stellette a piccoli ferri. Il piatto posteriore, identico nel decoro, reca al centro l’iscrizione su tre linee ‘Suora Livia Zanona’. Dorso a 5 cordoni e 4 cordoncini decorati alternativamente con filetti e segmenti obliqui, negli scomparti decoro a piccoli ferri. Tagli in oro zecchino inciso a bulino con il motivo dei cordami intrecciati; tracce di fermagli.”)

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1338

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/10) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarcha (Venice 1547) [probably, not certainly the Giolito edition with Vellutello commentary]

provenance

● Per Hierta (1864-1924)

literature

Johannes Rudbeck, Ex Bibliotheca fraemmestadiensi; festskrift tillägnad friherre Per Hierta på hans femtioårsdag den 25 oktober 1914 (Stockholm 1914), Fig. 18

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1326quat

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, pp.173-174 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/11) Innocenzio Ringhieri, Cento giuochi liberali, et d'ingegno, nouellamente da m. Innocentio Ringhieri gentilhuomo bolognese ritrouati, et in dieci libri descritti (Bologna: Anselmo Giaccarelli, 1551)

provenance

● Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572, created Cardinal 1538)

● George Spencer Churchill, Duke of Marlborough (1766-1840)

● R.H. Evans, White Knights library. Catalogue of that distinguished and celebrated library, Part II, London, 22 June-3 July 1819, lot 3582 (“ornamented binding in compartments” [link])

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (£1 5s)

● Richard Heber (1773-1833)

● Sotheby & Son, Bibliotheca Heberiana. Catalogue of the library of the late Richard Heber, Esq. Part the Ninth. Removed from Hodnet Hall, 11-26 April 1836, lot 2655 (“fine copy, in old richly ornamented binding in compartments. Liber olim Cardinalis Hippolyti Estensis” [link])

● Bohn - bought in sale (£1 8s)

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866)

● Sir George Lindsay Holford (1860-1926)

● Robert Stayner Holford (1808-1892)

● Sotheby & Co., The Holford Library: Catalogue of extremely choice & valuable books principally from continental presses, and in superb morocco bindings, forming part of the collections removed from Dorchester House, Park Lane, the property of Lt.-Col. Sir George Holford, K.C.V.O. (deceased), London, 5-9 December 1927, lot 707 (“contemporary North Italian binding, vellum, the sides decorated with an elaborate arabesque design stamped in black, lettered in the centre (1) of the upper cover r. hipolito; (2) of the lower cover estense (Cardinal Hippolyto of Este); back decorated with small tools in black, gauffred edges; from the White Knights-Heber-Vernon collections” [link])

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£80); their Catalogue 520 (London 1936), item 711 (£65; “in a contemporary vellum binding stamped in black to an elaborate arabesque design, with the name of Cardinal Hippolyto d’Este stamped on the sides, ‘R. Hipolito’ on the upper cover and ‘Estense’ on the lower, the back decorated with small tools, gauffered edges”)

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 584 (“A Bolognese binding by the Pflug and Ebeleben workshop … one of the very few Renaissance bindings tooled in black on vellum (another is reproduced by T. de Marinis, La legatura artistica, II, pl. 226)”)

● Librairie Jean Hugues, Paris - bought in sale (£480)

● Amsterdam, Universiteits Bibliotheek, OTM: Band 1 C 15 (images, [link])

literature

Burlington Fine Arts Club, Exhibition of bookbindings (London 1891), Case E-17 & Pl. 26 (“Italian binding of the 16th century; white vellum; elaborately tooled in black. The book formerly belonged to cardinal Hippolyto d’Este, whose name is stamped upon the covers. R.S. Holford, Esq.”)

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), no. 68

De Marinis, op. cit, 1960, no. 1331

Foot, op. cit. 1978, pp.303, 306

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.174 ([decorated by] “one plaque in two parts, upper and lower” “used mainly, and perhaps exclusively, by the ‘Pflug and Ebeleben Binder’”)

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.29

(I-D/12) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarcha con l’espositione d’Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Bartolomeo Zanetti, for Alessandro Vellutello & Giovanni Giolito De Ferrari, 1538)

provenance

● Marcantonio Totila (fl. 1527-1550), supralibros

● Anton Giulio Brignole Sale (1605-1662)

● Genoa, Biblioteca Berio, BCBS B.S.XVI.B.87

literature

Laura Malfatto, Da Tesori privati a bene pubblico: le collezioni antiche della Biblioteca Berio di Genova (Ospedaletto [Pisa] 1998), no. 11

(I-D/13) Francesco Petrarca, Sonetti, Canzoni, e Triomphi di messer Francesco Petrarcha con la spositione di Bernardino Daniello da Lvcca (Venice: Giovanni Antonio Nicolini da Sabbio, March 1541)

provenance

● unidentified owner(s), inscription “T.B” in ink on title-page, “Cipriani” in pencil on lower cover

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.55 (opac Legatura in pelle “alla Grolier”. Piatti decorati con fregi fitomorfi dorati. Nello specchio, motivo a mandorla con incisione petrarcha dil danielllo e piccolo cupido. Quattro fori pe legacci. Dorso a 7 nervi. Taglio dorato. [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1323

(I-D/14) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarcha con l'espositione d’Alessandro Vellutello di nouo ristampato con le figure a i Triomphi, et con piu cose vtili in varii luoghi aggiunte (Venice: Gabriel Giolito De Ferrari, 1544)

provenance

● Libreria antiquaria Hoepli, Incunables, manuscrits, livres rares et précieux, autographes musicaux, quelques romantiques, quelques livres modernes, reliures, Zurich, 29 October 1937, lot 119 & Pl. 74 (“Reliure éditoriale des Giolito …maroquin marron; dos à nerfs divisé en 8 compartiments décorés de petits fers entrelacés; large cadre sur les plats composé de rinceaux dorés et limité par deux filets dorés; à l'intérieur une riche ornementation de petits fers, d'aides pleins, de rinceaux et d'étoiles en or; au milieu du plat supérieur le titre frappé: IL PETRARCHA; au milieu du plat inférieur Cupidon tendant son arc, entouré de flèches volantes; tranches dorées")

type e: binder of ulrich fugger’s bible

(I-E/1) Dioscorides Pedanius, De medica materia (Basel: Michael Isengrin, 1542)

provenance

● Marcantonio Totila (fl. 1527-1550), supralibros

● unidentified owner, inscription “Fabian Beninij” [Hobson & Quaquarelli, as “A di 18 de Magio 1590 di me Fabian Beninij aromatarij Bologesse”]

● Lodovico Montefani Caprara (1709-1785), his inscriptions “Ulissis Aldrouandi et amicorum. C8” on title-page and “U.A.” on front endpaper

● Bologna, Biblioteca universitaria, Raro B. 62

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.171 no. 8 [as bound by the Binder of Ulrich Fugger’s Bible]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.27 no. 8 & no. 42 (upper cover illustrated)

(I-E/2) Antonio de Guevara, Institutione del prencipe christiano. Tradotto di spagnuolo in lingua toscana per Mambrino Roseo da Fabriano. Nuouamente stampato, & con somma diligenza riconosciuto (Venice: Luigi Torti, 1544)

provenance

● Maurice Burrus (1882-1959)

● Alde & Isabelle de Conihout with Pascal Ract-Madoux, Livres anciens du XVe au XIXe siècle : Voyages, sciences, médecine, Paris, 16 March 2022, lot 11 (“Très élégante reliure bolognaise, attribuable au Relieur de la bible d’Ulrich Fugger actif entre 1533 et 1550 … Prov. Un possesseur du XVIe (signature marge f. 90v, soulignements et note XVIe ‘Consegli del principe’ ff. 97 à 100) - Maurice Burrus (son ex-libris et marque d'acquisition en 1934) … Coiffes et coins très habilement restaurés, haut du plat inférieur refait et redoré, dos refait, gardes renouvelées” [link]) [RBH 31622-11]

● unidentified owner – bought in sale (€1750)

literature

Unrecorded

(I-E/3) Girolamo Malipiero, Il Petrarcha spirituale, ristampato nuouamente, et dall’ authore corretto (Venice: Francesco Marcolini, September 1538)

provenance

● Marcantonio Totila (fl. 1527-1550), supralibros (obliterated)

● unidentified owner (?), supralibros, “Constantia” lettered on spine

● unidentified owner, inscription “Franciscus Gianibellus” (Giambelli) in red ink on title-page (17C)

● William Bateman, FSA (1787-1835), armorial exlibris “W.m Bateman, F.A.S., of Middleton-by-Youlgrave, in the County of Derby”

● Giovanni Gancia, Brighton & Paris

● Delbergue-Cormont & Librairie Bachelin-Deflorenne, Catalogue de la Bibliothèque de M. G. Gancia composée en partie de livres de la première bibliothèque du Cardinal Mazarin et d’ouvrages précieux, Paris, 27 April-2 May 1868, lot 560

● Delbergue-Cormont & Adolphe Labitte, Catalogue des livres et manuscrits rares et précieux composant le cabinet de M. Gancia, Paris, 11-12 April 1872, lot 222

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 47)

● Capt. Charles Ludovic Lindsay (1862-1925), inkstamp

● John Henry Montagu Manners, 9th Duke of Rutland (1886-1940), acquisition inscription, dated 1925

● Manners, family library (Belvoir Castle), inkstamp

● Marlborough Rare Books, London; their Catalogue 146: Fine bindings and distinguished provenances (London [1992]), item 3 (£12,500); Catalogue 160: Fine bindings and distinguished provenances (London [1995]), item 6 (£7500)

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased from the above, 1996 [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #2097]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance library: magnificent books and bindings, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 60 [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($10,160) [RBH N11245-60]

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.171 no. 7 [as bound by the Binder of Ulrich Fugger’s Bible]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, p.27 no. 7

(I-E/4) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarca (Venice: Heirs of Aldus Manutius & Heirs of Andreas Torresanus, June 1533)

provenance

● unidentified owner(s), supralibros, initials C.B.P.F.I.S. on lower cover, verses of several sonnets underlined, those of sonnets 106 to 108 lined through in brown ink

● unidentified owner, inscription “Di Ferrante del Monte” (“e Borbone”, added later), perhaps Ferrante Bourbon del Monte (1540-1589), marchese di Santa Maria, Nobile Romano e Patrizio di Perugia

● unidentified owner, inscription “Di Luduvic Pravi” (17C)

● Lt Col. Bryan Palmes (1851-1932), exlibris [lots 90-113a identified in Sotheby’s catalogue as property of “Lt.-Col. Bryan Palmes, of Villa Mezzomonte, Capri, Italy”]

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable printed books, illuminated & other manuscripts, also of autograph letters & historical documents, London, 25-26 July 1923, lot 100 (“early inscription on title … contemporary Italian brown morocco, sides elaborately gilt tooled with floral scrolls, arabesques, etc. leaving a space in the centre occupied, on the upper cover by the title, and on the lower by the initials C.B.P.F.I.S. tooled back, gilt and gauffered edges”)

● “Villars” - bought in sale (£17 10s)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of printed books, comprising … a large and interesting collection of stamped and armorial bindings, etc., London, 24-25 November 1924, lot 121 (erroneously dated “1553”; “Italian brown morocco, sides elaborately gilt tooled with floral scrolls, arabesques, etc., leaving a space in the centre occupied on the upper cover by the title, and on the lower by the initials ‘C.B.P.F.I.S.’, tooled back, gilt and gauffred edges”) [offered among “Other Properties”]

● Spiers - bought in sale (£13 10s) [Book Prices Current, 39, p.691]

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable printed books and a few illuminated manuscripts, London, 15-16 February 1926, lot 274 [entered among “Other Properties”]

● Ellis, London - bought in sale (£9 10s) [Book Prices Current, 40, p.707]

● J.J. Holdsworth and George Smith, trading as Ellis; their Catalogue 241: A catalogue of fine old bookbindings (London [1926]), item 153 (“the upper cover with the words ‘Il Petrarcha’, the lower cover with the initials C.B.P.F.I.S.”) & Pl. 4

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982)

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York; their Catalogue 104/II: Fine books in fine bindings from the fourteenth to the present century (New York 1981), item 152 ($6500)

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased from the above, 1981 [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0371]

● Sotheby's, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection: N-Z, New York, 25 June 2025, lot 1300 ($22,860) [RBH N11571-1300]

literature

Rudolf Adolph, Hans Fürstenberg (Aschaffenburg 1960), p.40 (illustrated)

Exposition de reliures de la Renaissance: collection Jean Furstenberg: 30 September 1961 (Paris 1961), no. 89

Musée d’art et d'histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 52

De Marinis, op. cit. 1966, pp.108-109

Foot, op. cit. 1978, p.304 ([associating this binding with] “a second shop in Bologna, which produced lavishly tooled bindings, using the same type of tools as were employed in the shop that worked for Pflug and Ebeleben”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, p.171 no. 6 [as bound by the Binder of Ulrich Fugger’s Bible]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.27 no. 6

(I-E/5) Francesco Petrarca, [possibly Il Petrarcha con l'espositione d’Alessandro Vellutello di nouo ristampato con le figure a i Triomphi, et con piu cose vtili in varii luoghi aggiunte (Venice: Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari, 1545)]

provenance

● unknown

literature

Martin Gerlach, Das alte Buch und seine Ausstattung vom XV. bis zum XIX. Jahrhundert: Buchdruck, Buchschmuck und Einbände (Die Quelle, Mappe 13) (Vienna [1915]), Tafel 38 [link]

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1326ter ([claimed to be Venice: Giolito, 1545 edition]; “Marr. castano; ricca decorazione dorata poco dissimile dal n. 1320 [MS “Libro per farsi bella”]; sul piatto anteriore il titolo: Il / Petrar / cha / Del Vellv”)

Schunke, op. cit. 1974, p.266

Hobson, op. cit. 1998, pp.171-172 no. 10 [as bound by the Binder of Ulrich Fugger’s Bible]

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.28 no. 10

types f-k: panels used by anonymous binders

(I-F/1) Jacopo Sannazzaro, Arcadia di m. Giacomo Sanazaro con la gionta (Toscolano: Paganino Paganini & Alessandro Paganini, [ca 1527-1533])

provenance

● Bologna, Biblioteca comunale di Bologna all’Archiginnasio, 16.K.VII.29 (opac, [link])

literature

Federico Macchi, A fior di pelle: Legature bolognesi in Archiginnasio (second edition, Bologna 1999), p.22 no. 16

Legature storiche dell’Archiginnasio (“Cuoio di bazzana marrone su cartone decorato a secco e in oro. Cornice caratterizzata da foglie d’edera e da minute stelle. Specchio provvisto di decoro a placca (130x60 mm) raffigurante motivi muti di gusto orientaleggiante: il putto alato a piena figura con arco in equilibrio sul globo al piatto anteriore, la Fortuna su quello posteriore.” [link, link])

(I-G/1) Francesco Petrarca, Francisci Petrarchae De remediis vtriusque fortunae. Libri II (Venice: Alessandro Paganini, 1515)

provenance

● Bologna, Biblioteca Universitaria, Raro A.44 (opac, [link])

literature

Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Catalogo online delle legature storiche (“Cuoio di capra bruno su quadranti in cartone decorato a secco e in oro. Filetti concentrici. Diverse le placche ai piatti provviste di motivi di gusto orientaleggiante.” [link])

(I-H/1) Francesco Petrarca, Li sonetti, canzoni, et triomphi di m. Francesco Petrarcha historiati. Nuouamente reuisti, & alla sua integrita ridotti (Venice: Francesco Bindoni & Maffeo Pasini for Agostino Bindoni, 1542)

provenance

● Bologna, Biblioteca Universitaria, A.V.HH.XI.35 (opac, [link])

literature

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.101 no. 49 (upper cover illustrated)

Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Catalogo online delle legature storiche (“Cuoio bruno su quadranti in cartone decorato in oro. Placca (145x97 mm) di foggia orientaleggiante; braciere ardente al centro.” [link])

(I-I/1) Luigi Alamanni, Opere toscane di Luigi Alamanni al christianissimo re Francesco primo (Venice: Heirs of Lucantonio Giunta, 1542)

Image courtesy of Federico Macchi

provenance

● Plinio Fraccaro (1883-1959)

● Pavia, Universitaria, Fondo Fraccaro, 68 H 14

literature

Federico Macchi, Legature storiche nella biblioteca “A. Mai” (“La Biblioteche Trivulziana di Milano e Universitaria di Pavia, possiedono rispettivamente un inedito esemplare di questo genere (Milano, Trivulziana: Opere toscane di Luigi Alemanni, Venetiis, apud haeredes Lucae Antonii Juntae, MDXLII, segnatura Triv. L 1613; Pavia, Universitaria: Fondo Fraccaro, segnatura 68 H 14)” [link])

(I-I/2) Theodorus Gaza, Theodori Grammatices libri. IIII. De mensibus liber eiusdem. Georgii lecapeni de constructione uerborum. Emmanuellis Moscopuli de constructione nominum & uerborum. Eiusdem de accentibus. Hephaestionis Enchiridion (Florence: Heirs of Filippo Giunta, April 1526)

provenance

● Bologna, Biblioteca Universitaria, A.V.Z.XIV.18

literature

Hobson & Quaquarelli, op. cit. 1998, p.101 no. 50 (upper cover illustrated)

Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Catalogo online delle legature storiche (“Cuoio di bazzana bruno su quadranti in cartone decorato a secco e in lega d’oro. Decoro a placca (148x90 mm) di foggia orientaleggiante con putto alato arco e freccia al centro.” [link])

(I-I/3) Theodorus Gaza, Theodori Grammatices libri. 4. De mensibus liber eiusdem. Georgii lecapeni de constructione uerborum. Emmanuellis Moscopuli de constructione nominum & uerborum. Eiusdem de accentibus. Hephaestionis Enchiridion (Florence: Heirs of Filippo Giunta, April 1526)

provenance

● Brescia, Biblioteca Queriniana, Salone F XVI 41 (opac, [link]; digitised, [link])

literature

Fedderico Macchi, “Legature cinquecentesche bolognesi alla Queriniana di Brescia” in Misinta 33 (2009), pp.29-48 (p.38 no. 6: “Cuoio marrone, su cartone, decorato a secco. Sui piatti, un’ampia placca (170x100 mm) di foggia orientaleggiante, caratterizzata al centro, da un cupido alato munito di un arco con freccia nell’arco, entro motivi ad arabeschi.” [link])

(I-J/1) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarcha col commento di m. Sebastiano Fausto da Longiano, con rimario et epiteti in ordine d'alphabeto. Nuouamente stampato, 1532 (Venice: Francesco Bindoni & Maffeo Pasini, 1532)

provenance

● Biblioteca del Collegio Gesuita (opac)

● Piacenza, Biblioteca Passerini-Landi, (C) G.12.12 (opac pelle con impressioni a secco, cucitura su 3 enrvi)

literature

Catalogo delle legature storiche di pregio della Biblioteca comunale Passerini-Landi, Parte prima, no. 169A (“Legatura della prima metà del secolo XVI, eseguita in Italia, del genere ‘a placca’ … Piatti ornati con una placca (140x65 mm) di foggia orientaleggiante” [link])

(I-K/1) [Manuscript] Officium B. Mariae Virginis secundum ordinem Fratrum Praedicatorum, cum VII psalmis poenitentialibus, Officium Mortuorum et officio Sanctorum in comuni (15C)

provenance

● Antonio Magnani (1743-1811); bequeathed in 1811 the Biblioteca Magnani to

● Bologna, Biblioteca comunale di Bologna all’Archiginnasio, Manoscritti A 247

literature

Inventari dei manoscritti delle biblioteche d'Italia. Volume XXX Bologna (Florence 1924), A247

Federico Macchi, Legature storiche dell’Archiginnasio (“Cuoio bruno su cartone decorato a secco e in oro. Cornice costituita da coppia di filetti perlati. Specchio caratterizzato da decoro a piatto campito del genere orientaleggiante. Al centro del piatto anteriore la Madonna a mezza figura e il Bambino entro il crescente, in quello posteriore la scritta in caratteri capitali ‘S./Camila/ deside/ria’. Tracce di due fermagli costituiti da bindelle in cuoio marrone con puntale dal margine inciso nella porzione superiore (parzialmente scomparsa quella al piede) inserite sotto il materiale di copertura e da altrettanti tenoni in ottone a riccio vuoto.”[link, link])