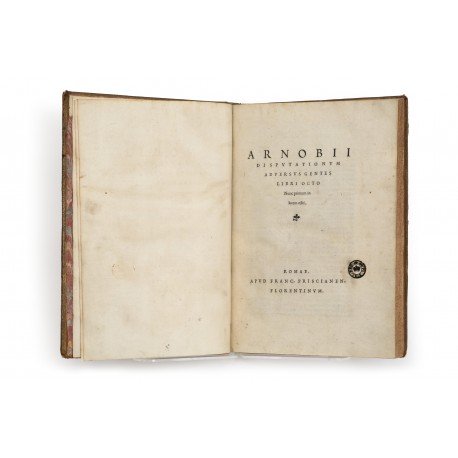

Disputationum adversus gentes libri octo. Nunc primum in lucem editi

- Subjects

- Apologetics, Christian - Early works to 1800

- Authors/Creators

- Arnobius Afer, died circa 330

- Printers/Publishers

- Priscianese, Francesco, active 1542-1547

- Owners

- Royal Library, Copenhagen

- Suhm, Peter Frederik, 1728–1798

- Other names

- Minucius Felix, Marcus, active 200-240

- Sabeo, Fausto, 1478-1558

Arnobius Afer

died circa 330

Disputationum adversus gentes libri octo. Nunc primum in lucem editi.

Rome, Francesco Priscianese, 1542

folio (308 mm), (108) ff. signed a2 &2 π1 (privilege) A–P6 R8 (–R8, cancelled, probably = π1) and foliated (5) 1–102 (1).

provenance Peter Frederik Suhm (1728–1798), his inscription ‘Sühm’ imperfectly erased from title-page1 — Royal Library, Copenhagen, stamp on title-page in black ink Dupl. Bibl. Reg. — label with printed inventory number 249 in upper corner of front pastedown — Reiss & Sohn, Auktion 118, Königstein im Taunus, 22 April 2008, lot 710

Abrasions to binding corners, otherwise in very good state of preservation.

binding seventeenth-century polished calf; back decorated in gilt.

First edition of Arnobius’ seven books attacking the pagans, his only surviving work, written at Sicca (modern El Kef) about 302–305, to refute the heathen charge that Christianity was the cause of many terrible afflictions which had fallen upon the Roman empire, including pestilence, droughts, wars, famine, locusts, mice, and hailstorms. It is a mine of information about the temples, idolatrous worship, and Greco-Roman mythology of his time, and was thoroughly exploited by Renaissance antiquarians.

The eighth book printed here (‘Liber de errore profanarum religionum’), a dialogue between two Christian converts and a cultivated Roman pagan while walking by the sea at Ostia, is a work of the Latin Christian apologist Marcus Minucius Felix (fl. 200–240 ad), as the humanists Adriaen de Jonghe and François Baudouin found out years later.

The editor, Fausto Sabeo of Bressanone (1478–1558), keeper of the Vatican library, states that he discovered the manuscript in Switzerland or Germany (‘iure belli meus est Arnobius, quem e media barbarie non sine dispendio, et discrimine eripuerem’, folio a2 verso) and acknowledges the help of Girolamo Ferrari (1501–1542) and the publisher, Francesco Priscianese, in correcting some passages. Sabeo dedicated the edition to François i of France ‘because of his love for literature and his firm attitude towards the new Lutheran heretics’,2 and later presented the manuscript to the King (now in Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Lat. 1661).3

The book was part of a vast, uncompleted project initiated by Cardinal Marcello Cervini, in 1542, of which the others were Greek editions of Homer and Theophylactus (both Rome: Blado & partners, 1542) and Nicholas i, Epistolae (Rome: Francesco Priscianese, 1542).4 Printing commenced on 22 January 1542, but was not completed until 18 October 1543. The dedicatory letter to François i is dated ‘cal. Septembris mdxliii’ in all copies; in some the colophon is dated 1542 (as here), in others 1543.

ink stamp Dupl. Bibl. Reg. of the Royal Library, Copenhagen.

P.F. Suhm’s ownership inscription in a copy of Johann Cramer, Predigt bey Gelegenheit des Geburtstages des Königes (Copenhagen 1757). Originally in the library of Princess Charlotte Amalie of Denmark (1706–1782), this volume was sold as a duplicate by the Royal Library in 1786, when purchased by Suhm. It was reacquired when Suhm sold his collection of c. 100,000 volumes to the Royal Library in 1796.

The huge library (some 100,000 volumes) of the Danish writer P.F. Suhm was purchased in 1796 by the Royal Library, Copenhagen, and duplicates were dispersed over many years.5

references British Museum, Short-title catalogue of Italian Books (London 1958), p.56; H.M. Adams, Catalogue of books printed on the continent of Europe, 1501–1600, in Cambridge libraries (Cambridge 1967), A–1994; Fernanda Ascarelli, Le Cinquecentine romane (Milan 1972), p.12; Le edizioni italiane del xvi Secolo: Censimento nazionale (Rome 1990), A–2827

1. Harald Ilsøe, ‘Nogle upåagtede kilder til P.F. Suhms bibliotek’ in Magasin fra Det kongelige Bibliotek 10 (no. 3, 1995), pp.47–56.

2. Marsilio Ficino e il ritorno di Ermete Trismegisto: Marsilio Ficino and the Return of Hermes Trismegistus, catalogue of an exhibition held in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, and Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, Amsterdam (Florence 1999), pp.158–160 no. 15 (quotation p.158).

3. Yves-Marie Duval, ‘Sur la biographie et les manuscrits d’Arnobe de Sicca’ in Latomus 45 (1986), pp.79, 87–91; Alessandro Cutolo, Un Bibliotecario della Vaticana nel xvi secolo (Milan 1949), pp.29–31. The binding proves that Henri ii (king from 1547) owned the manuscript.

4. For details of the project, see Léon Dorez, ‘Le cardinal Marcello Cervini et l’imprimerie à Rome (1539–1550)’ in Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire 12 (1892), pp.289–313 (esp. p.306); Angela Nuovo, The Book Trade in the Italian Renaissance (Leiden & Boston 2013), pp.61–65.

5. On the dispersal of duplicates by the Danish Royal Library, see Harald Ilsøe, ‘Bøger der gik den anden vej: Historien om hvad der blev af Det Kongelige Biblioteks dubletter’ in Fund og Forskning 37 (1998), pp.11–62 (website). Compare our title-page with the title-page in a book sold at auction by the Royal Library in 1786 (duplicate stamp), where purchased by Suhm (ownership inscription), subsequently returned to the Royal Library in 1796 with the acquisition of Suhm’s collection (image).