Opera [edited with a commentary by Christophorus Landinus]

- Subjects

- Literature, Classical

- Authors/Creators

- Horatius Flaccus, Quintus, 65 BC-8 BC

- Artists/Illustrators

- Elliott, Thomas, active 1703-c. 1723

- Printers/Publishers

- Gregori, Giovanni de', active 1480-1517

- Owners

- Child, Francis, MP, c. 1735-1763

- Fairfax, Bryan, 1676-1749

- Harley, Edward, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, 1689-1741

- Jersey, Victor Albert George Child Villiers, 7th Earl of, 1845-1915

- O’Brien, William, 1832-1899

- Peutinger, Konrad, 1465-1547

- Other names

- Bild, Veit, 1481-1529

- Landino, Cristoforo, 1424?-1498

Horatius Flaccus, Quintus

Venosa 65 bc – 8 bc Rome

Opera [edited with a commentary by Christophorus Landinus]

Venice: Johannes de Gregoriis, de Forlivio, et Socii, 17 May 1483

Chancery folio (293 × 195 mm), (206) ff., signed [A]6 a-z8 &8 [con]8, 54 lines and headline, roman type, 8-line initial spaces with printed guides.

contents A1 recto blank; A1 verso Angelus Politianus, Ode dicolos tetrastophus [addressed to] Q. Horatius Flaccus; A2 recto Christophorus Landinus, Proemium; A3 recto Tabula vocabulorum; A6 recto Haec sunt quae in codice Horatii errore librarii mendosa emendanda fuerant; Emendata in comentariis quae inuenies; A6 verso Registrum (colophon) a1 recto Christophorus Landinus, Vitae poetae; a2 verso Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Carmina; o3 recto Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Epodae; p6 recto Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Carmen saeculare; p7 verso Horatius Flaccus, Ars poetica; (commentary on Ars poetica addressed to Guidubaldus de Montefeltro); r3 verso Horatius Flaccus, Sermones; (commentary on Sermones addressed to Guidubaldus de Montefeltro); y1 verso Horatius Flaccus, Epistolae; (commentary on Epistolae addressed to Guidubaldus de Montefeltro).

provenance Konrad Peutinger (1465–1547), annotations — Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer (1689–1741) — bought by Thomas Osborne (1704–1767), bookseller, price (1–10–0) written in pencil on endpaper, excision of the top right-hand corner to remove his earlier price1 — Bryan Fairfax (1676–1749), Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge — Robert Fairfax, 7th Lord Fairfax of Cameron (1707–1793), by whom consigned to — John Prestgate, A catalogue of the entire and valuable library of the Honourable Bryan Fairfax, Esq, London, 26 April 1756, p.4 lot 1242 — Francis Child, mp (c. 1735–1763), Osterley Park, Middlesex, shelfmark viii. 2. 163 — by descent to Victor Albert George Child Villiers, 7th earl of Jersey (1845–1915), exlibris (Franks 30399) — Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, The Osterley Park Library, London, 6 May 1885, p.56 lot 841 (link) — William O’Brien (1832–1899), his bequest (commemorative label, dated 1899) — Schools of Philosophy and Theology, Milltown Park, Dublin, labels4 — Sotheby’s, The Library of William O’Brien: Property of the Milltown Park Charitable Trust, London, 7 June 2017, lot 191 (£8125; link)

Occasional worming, binding rubbed and worn along joints and edges.

binding gold-tooled crimson goatskin over pasteboards, attributable to Thomas Elliott, c. 1722, for Edward, Lord Harley (see below).

The complete works of Horace with the commentary of Cristoforo Landino, a copy owned and annotated by the Augsburg jurist, collector, and scholar Konrad Peutinger (1465–1547).5 In the early 1720s, when the first of Peutinger’s books and manuscripts entered the market, it was bought by the English bibliophile Edward Harley (1689–1741) for the Harleian Library. The book passed thereafter through the hands of the bookseller Thomas Osborne into the library of Bryan Fairfax (1766–1749), thence to Francis Child (c. 1735–1763), and by descent to Victor Albert George Child Villiers, 7th earl of Jersey (1845–1915), whose Osterley Park Library was sold in 1885. Since then, it has been in the William O’Brien (1832–1899) collection, its Peutinger provenance unrecognised.

Konrad Peutinger

The remarkable library of Konrad Peutinger has recently been the subject of much research. Two catalogues of its contents are preserved in Peutinger’s own hand, one written in 1515 and updated until about 1523, the other written in about 1523 and updated until two years before the collector’s death, on 28 December 1547 (the latest entries are in another hand). They reveal one of the largest private collections north of the Alps, approximately 6000 works bound in 2200 volumes. In addition to these autograph catalogues, the library is documented by inventories taken in 1597 and 1613–1635/1636, and by about 600 pages of detailed notes made by Andreas Felix von Oefele, who had access to the library in the eighteenth century. A project sponsored by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and led by Hans-Jörg Künast and Helmut Zäh aims to reconstruct Peutinger’s dispersed library, identifying the precise editions to which Peutinger’s entries refer, and locating the surviving copies. Their work is based on the 1523–1545 catalogue, which offers more details than its predecessor. Two volumes have appeared so far, one presenting Peutinger’s non-legal books, the other his professional library; a further volume publishing information culled from the later documentation together with comprehensive indices is envisaged. In the meantime, a collection of essays in celebration of Peutinger’s 550th birthday has just appeared.6

Peutinger expressed his ownership in multiple ways, sometimes inserting a woodcut exlibris,7 sometimes inscribing his name or motto on an endpaper or on the first leaf,8 sometimes annotating the upper cover, back, or page-edges with the author’s name, or the book title, or the shelfmark that he assigned to the volume.9 He occasionally wrote an index on the binding paste-downs or free-endpapers.10 Often, no explicit indication of his ownership has survived rebinding, and Peutinger’s possession of a book is established through comparison of the handwriting of marginalia and by reference to the catalogues of his library. Our 1483 Horace is one such volume.

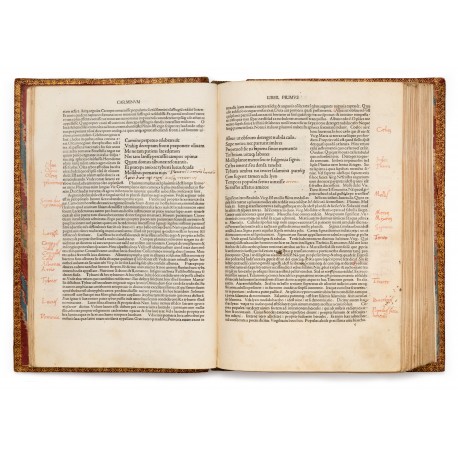

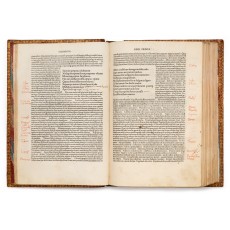

Fig. 1 (folios b8 verso–c1 recto) Emendations in brown ink in Odes, 1.7.8-9 (plurimus in Iunonis honorem / aptum dicet equis argos ditesque mycenas – these lines omitted by the compositor), 1.7.23 (corona – word omitted by compositor). The red marginalia are in Peutinger’s hand.

Fig. 2 (h3 verso–h4 recto) Emendations by erasure and brown ink in Odes 1.13.21 (furuae for futurae), 1.13.23 (et), 1.23.24 (querentem for canentem), 1.13.30 (umbrae dicere – word omitted by compositor), 1.13.30 (centiceps for centipes). The red marginalia are in Peutinger’s hand.

Peutinger’s library catalogues

The 1483 Horace is entered in Peutinger’s first library catalogue, written about 1515, when he reorganised his library – already more than 1000 volumes – following his purchase of a house near the Cathedral, and updated until 1522/1523.11 To impose order on the library, Peutinger catalogued his books by subject, shelfmark, and author, and arranged them on the shelves by size and type of binding (wooden boards, vellum, or leather). He classified this book under the rubric ‘Poetae’, identified it as a folio bound between wooden boards, and indicated that it had been mislaid: ‘deficiunt – Antiquus Horatius’.12 The catalogue records that Peutinger also possessed two copies of Horace printed in small format, evidently Aldine or Giunta editions (or Aldine counterfeits) of the early sixteenth century.13

Comparative illustrations Entries for our volume (‘5 Horatius Flaccus cum’) in Peutinger’s autograph library catalogue of 1515–1523. The second entry (‘deficiunt Antiquus Horatius’) records the book as ‘missing’. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, HSS Clm 4021b (folios 53v, 74v link)

When Peutinger rewrote his library catalogue, in 1523,14 he does not list the ‘Antiquus Horatius’ – presumably because it was still missing. A new folio edition of Horace is entered, described in Peutinger’s catalogue as containing commentaries written by Antonius Mancinellus and others.15 By 1597, when the library was inventoried by a notary to settle a family dispute, the ‘Antiquus Horatius’ had been recovered: both folios are recorded by the notary, along with the two octavo editions.16 All four volumes reappear in a corrected version of that inventory written between 1613 and 1635/1636.17

Comparative illustration Entry for our volume (‘Opera Horatii’) in a notarial inventory taken in 1597. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, HSS Clm 4021d (folio 51r, link)

The 1483 Horace apparently was in the library when it was bequeathed by Peutinger’s last male descendant, Desiderius Ignaz von Peutingen (1641–1718), to the Augsburg Collegium St Salvator. As soon as it became their property, the Jesuits began to sell valuable books and manuscripts. The volumes they chose to retain were inscribed Soc Jesu Augustae (or variation thereof) and assigned shelfmarks (letter/Roman numeral/Arabic numeral, like K/V/83). The school survived the suppression of the Jesuit order, but not the secularisation of ecclesiastical properties: it closed in 1807, when the library was divided between the local Stadtbibliothek and the Hofbibliothek in Munich.

Veit Bild

Peutinger in known to have lent a copy of Horace to Veit Bild (1481–1529), allegedly so that Bild could make corrections in his own copy. After brief study at Ingolstadt (1499–1500), where he was a pupil of Jakob Locher, the poet laureate, Bild was appointed parish secretary (scriptor parochiae) by the Benedictine Kloster Sankt Ulrich und Afra in Augsburg; in April 1503 he became a novice in that monastery, and on 2 February 1504 he made his monastic profession and was ordained to the priesthood. Teaching Latin to the novices became his main task.18

The exact date that Bild borrowed the Horace is not known, however it likely was c. 1502–1504, a period during which Bild is said to have been preoccupied with poetry.19 Bild expressed his gratitude to Peutinger in a poetic composition, preserving a copy in an anthology of his own writings which he compiled during the years 1506–1510: ‘Varia carmina ante religionis ingressum composita, inter quae quaedam ad… Conradum Peittinger’.20 Although Bild never became a member of the Sodalitas Peutingeriana, he corresponded regularly with Peutinger, and became father confessor of Peutinger’s son, Karl. In two letters dated 1513, he asked to borrow from Peutinger a Greek dictionary and a copy of Ovid’s Fasti.21

The commentary in our book is extensively annotated in Peutinger’s large, controlled hand.22 Peutinger read the book from cover to cover, sustaining a high level of attention throughout, methodically extracting from Landinus’s commentary key words, concepts, and authors’ names, and writing them in the margins. Occasionally, Peutinger identifies persons and things referenced but not named by Landinus. He evidently returned to the book several times, since his annotations are made using different pens and in red and brown inks. Key passages are signalled using a visual shorthand of marginal borders with ornate flourishes and manicules. Two annotations are in Greek (folios s7 verso; x8 verso).

Fig. 3 (detail of folio b1 recto) Emendations in brown ink in Odes, 1.2.39-40 (acer et Mauri peditis cruuentum / uultus in hostem – these lines omitted by the compositor, who has repeated lines 35-36). The marginalia in red ink are by Peutinger.

Fig. 4 (detail of folio c3 recto) Emendations in brown ink in Odes 1.9.9 (Permitte for Premitte), 1.9.12 (nec veteres agitantur orni – line omitted by the compositor).

Fig. 5 (detail of folio d6 recto) Emendations by erasure and brown ink in Odes 1.17.2 (et for ad), 1.17.8 (colubras for colubros). The marginalia in red are in Peutinger’s hand; the annotation in brown ink (velox) is by an unidentified hand.

Fig. 6 (detail of folio e2 recto) Emendations in brown ink in Odes 1.21.10 (mares for matres, Apollinis – omitted by compositor), 1.21.11 (insignemque for insignem), 1.21.15 (Vestra for Vesta).

Fig. 7 (detail of folio g1 recto) Marginalia adjacent to commentary for Odes 2.2.2-13, by Peutinger (in red) and by an unidentified hand (in brown); emendation by erasure (seruiret for seruieret).

Fig. 8 (detail of folio g4 verso) Emendations in brown ink in Odes 2.5.18 (nocturno for nocturo), 2.5.24 (Crinibus for Crinius); headline supplied for Odes 2.6 (Ad Septimium de tybure et tareto).

Fig. 9 (detail of folio k1 verso) Emendations by erasure and brown ink in Odes 3.4.53 (quid typhoeus for quod typheus) 3.4.55 (rhoetus for rethus), 3.4.56 (iaculator for ioculator), 3.4.66 (di), 3.4.67 (odere for mouere), 3.4.69 (giges for gigas).

Fig. 10 (detail of folio l8 verso) The annotator’s conjecture in Odes 3.24.4 (mare punicum) is not confirmed by modern critics (mare publicum).

Fig. 11 (detail of folio m1 recto). Annotation in brown ink to Odes 3.24.50 (vel scelerum et omnes codices habent). Modern critics confirm mittamus, scelerum si bene paenitet. The marginalia in red are by Peutinger.

Fig. 12 (detail of folio m3 recto) Emendations in brown ink to Odes 3.27.7 (quid for cur; the reading accepted by modern scholars is cui), 3.27.9. (repetat for reputant), 3.27.12 (Sis licet for Scilicet).

Fig. 13 (detail of folio n1 verso) Emendations by erasure and brown ink in Odes 4.3.8 (minas for mina), 4.3.9 (Ostendet for Ostendit), 4.3.11 (et spissae nemus comae – line omitted by compositor), 4.3.18 (quae), 4.3.24 (spiro for spero, placeo for taceo).

Fig. 14 (detail of folio o5 recto) A manicule beside Horace’s truism in Epodes 4.6: fortune does not change nature; emendation in brown ink in 4.7 (te viam).

Fig. 15 (detail of folio o8 recto) Marginalia beside Epodes 8.1-8 by Peutinger, in two shades of red ink.

Fig. 16 (detail of folio p3 verso) Emendations by erasure and brown ink in Epodes 15.16 (intrarit for intrauit), 15.17 (nunc for numae), 15.22 (nirea for nerea); Epodes 16.1 (teritur for atteritur), 16.5 (uirtus for uiribus).

Fig. 17 (detail of folio r7 verso) Emendations in brown ink in the commentary to Sermones, 1.2.63-66, on the crime of adultery (donas for mittis, moechae for mechae).

Fig. 18 (detail of folio s7 verso) Marginalia beside Sermones 1.5.40.

Fig. 19 (detail of folio x8 verso) Marginalia beside Sermones 2.8.16.

Fig. 20 (detail of folio z3 recto) A manicule beside Horace’s dictum: whom have flowing cups not made eloquent.

Peutinger seldom engages with the text of Horace. The copious annotation of the Horatian texts is by two or more other hands, writing in brown ink. One hand outlines errors in the text with dotted lines, and inserts an alternative word nearby or in the page margin; in one instance, reference is made to manuscript readings (see Fig. 11).23 Another hand, writing in a darker ink, makes interlinear emendations. Corrections are made both by pen and by erasure (scratching out the incorrect reading and writing an improved reading over the top). Overall, the corrections have significantly improved the text; almost all agree with modern critical editions.

If this should be the volume borrowed by Vitus Bild, then one of these hands painstakingly correcting the text may be his. Examination of a broad range of samples of Bild’s handwriting might decide the issue.24

Earlier provenance

The blank last page is covered with pen trials, informal personal names (‘Antonio Gioanne’, ‘Joane’, ‘C<deleted> amatissmus meus’), the names of luminaries (‘Picus Mirandola’, ‘Marius philosophicus’), and sententiae (‘Calumnia est mendax et malitiosa’, Nonius Marcellus), all suggestive of usage as a schoolbook. One of the inscriptions seems to give the dates of an astrological event in Scorpio.

Annotations on the blank last page.

Peutinger had studied in Italy (Padua, Bologna, Florence, Rome) from 1482–1488, and was in Florence shortly after the publication there of Landinus’ Horatian commentary. He is reputed to have met at this time Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), himself a student in Padua in 1482, who afterwards followed a similar itinerary (Florence in 1484, Rome in 1485). In 1491, Peutinger travelled again through Italy, to receive his doctorate in law.

On the last page is an excerpt from Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s letter to his nephew Giovanni Francesco (1469–1533), to console him against the tribulations of the world. Pico’s letter was written 15 May 1492 and first printed in 1496.25 The inscription and printed text differ:

Inscription: Picus Mirandula extrema e[st] stultitia euangelia non credere cuius ueritatem apostolicae resonant uoces, prodigia probant, mundus testatur, ratio confirmat, helementa loquuntur et demones ipsi confitentur

Printed text: Magna enim profecto insania euangelio non credere, cuius ueritatem sanguis martitum clamat, apostolice resonant uoces, prodigia probant, ratio confirmat, mundus testatur, elementa loquuntur: Demones confitentur.

Most probably, this book was purchased by Peutinger second-hand,26 and the inscriptions covering the final page have nothing to do with him. It is nonetheless worth pointing out that Giovanni Francesco Pico della Mirandola later became Peutinger’s regular correspondent, and that Peutinger came to possess many of Giovanni Francesco’s books, as well as several by his uncle.27 Since Peutinger’s juvenile handwriting differs markedly from his later hand, sufficient samples of it ought to be reviewed before excluding the possibility that some annotations on this last page are his.28

The Harleian Library

As noted above, the Jesuits soon commenced the first in a series of sales that scattered Peutinger’s library across Europe, rendering much of it untraceable. Some of the choicest material was bought by agents for the English bibliophiles Robert and Edward Harley. The Harleian Library contained two copies of the 1483 Horace: one is described in the first volume of Thomas Osborne’s sale catalogue, published 1743, as bound in Moroccan goatskin; the other is described in the fifth and last volume of the catalogue, published 1745, as containing ‘notis Mss.’ and bound in the more valuable ‘Turkey’ leather.

The dealer upon whom the Harleys relied most heavily was Nathaniel Noel (fl. 1681–1753), a London bookseller with premises in Paternoster Row.29 Noel’s agent on the Continent was George Suttie, who often journeyed through the Rhineland and South Germany in search of manuscripts and early printed books. On 19 January 1721/1722, Edward Harley purchased at Noel’s ‘a great parcel of Books’ which Noel alleged had come from Holland. Among them were three manuscripts from churches at Augsburg30 and a group of manuscripts of Peutinger provenance.31 Although no list of the printed books contained in this ‘great parcel’ survives, it is very likely that the copy of the 1483 Horace with ‘notis Mss.’ was one of them.

Another source was John Gibson, described by the Harleys’ librarian, Humphrey Wanley, as a ‘Scots Gent[leman] buyer of Books’ with premises near Scrope’s Inn, opposite St Andrew’s Church, Holborn. On 4 May 1722, Wanley visited Gibson, examined and bought ‘a small parcel of [11] Mss. and a parcel of [18] old Printed Books divers’ alleged to have come out of Florence. The printed books were all Italian incunabula; among them was a copy of the 1483 Horace.32 This most likely is the copy described by Osborne as bound in Moroccan leather.

The binding

Several binders were patronised by the Harleys, however it is possible to associate the present binding with the shop of Thomas Elliott. Elliot’s earliest known work for Edward Harley was executed in January 1719/1720; by June 1721, he was being entrusted with the most precious books and manuscripts in the library.33

Binding by Thomas Elliott, c. 1722, for Edward, Lord Harley (305 × 215 × 40 mm)

The present volume is decorated in Elliott’s normal style for goatskin bindings.34 On both covers, triple gold fillets form a frame, within which are three rolls: on the outside, a foliate and five-petalled flower roll,35 the second is the same roll repeated; then a broader ornamental roll with a fleur-de-lis alternating with a scallop shell.36 Each cover has a lozenge-shaped centrepiece composed of individual tools.37 The compartments of the spine are decorated by individual tools;38 the turn-ins and edges of the boards are decorated by another roll: ‘an alternation of flower heads within nearly complete circles and a fern’, a typical feature of Elliott’s bindings.39

Peutinger’s books in the market

About 30 per-cent of Peutinger’s non-legal library is located by Künast and Zäh, chiefly in the Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg and in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, where the books were deposited some 200 years ago. The remainder is scattered across Europe, in the Studienbibliothek Dillingen (fourteen volumes),40 Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart (four volumes),41 Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen (three volumes),42 Universitätsbibliothek München (one volume),43 Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen (one volume),44 Biblioteka Uniwersytecka Breslau (one volume),45 Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (one volume),46 and Russian National Library (one volume).47 Most of these volumes were eighteenth or early-nineteenth century acquisitions; likewise, the books and manuscripts from Peutinger’s library recorded in England, in the British Library48 and Bodleian Library,49 were obtained 200 or more years ago.

The few books recorded in North American libraries – in Cambridge,50 New Haven,51 New York,52 Princeton,53 and San Marino54 – entered comparatively recently, more by accident it would seem than by purposeful collecting. This sparse holding of Peutinger’s books outside German libraries is owing to their infrequent appearance in the auction market: we handled a volume in 2000,55 and observed another pass through the London auction salerooms in 2009.56 As just two books are located by Künast and Zäh in private collections,57 future opportunities to acquire a book from Peutinger’s library appear to be limited.

references ISTC ih00448000 (87 holding institutions; link); Goff H448; IGI 4881; BMC V 339; BSB–Ink H–363; GW 13459 (‘Nach ISTC und GW-Inventaren ca. 90 weitere Exemplare’); CIBN H–277; Bod-inc H–207

1. Catalogus bibliothecae Harleianae in locos communes distributus cum indice auctorum (London 1743), i, p.179 no. 3748 (binding described as ‘Tegm. Maurit. Deaurat.’; link); or – more likely – v (1745), p.46 no. 804 (‘notis Mss. Corio turcico deaur.’; link). Osborne states on the title-page of the fifth volume that ‘the price [is] marked in each book’. In our book, as in many others from this library, the top corner of the first front endpaper has been cut off, ‘evidently where the original price had been written, for the purpose of lowering the price of a book that had failed to sell… As the prices were always marked only in pencil, it is odd that Osborne should have troubled to cut the leaf.’ (J.B. Oldham, Shrewsbury School Library bindings. Catalogue raisonné, Oxford 1943, p.114).

2. Sale catalogue entry: ‘Horatius Landini, C[orio]. T[urcico]. – Ven. 1483’. Cf. John F. Bennett, ‘Brian Fairfax and the Fairfax library’ in Antiquarian Book Monthly Review 15 (1988), pp.340–347, 386–391. The entire library (3087 volumes offered in 2343 lots) was bought en bloc by Francis Child and the auction sale cancelled.

3. Thomas Morell, Catalogus librorum in Bibliotheca Osterleiensi ([London?] 1771), p.74, as shelved among ‘Classis Octava. Classici, aliique scriptores latini’, at viii. 2. 16 (link). Morell also indicates a previous shelfmark: ‘4. 13’ (the deleted pressmark ‘5. 19’ inscribed in the copy may thus refer to its position in the Harleian or Fairfax libraries).

4. Paul Grosjean, Daniel O’Connell and William O’Brien, A Catalogue of Incunabula in the Library at Milltown Park, Dublin (Dublin 1932), pp.24–25 no. 69.

5. The Opera of Horace was first printed at Venice, Printer of Basilius, ‘De vita solitaria’, c. 1471–1472. Landinus’s was the first humanist commentary on Horace, dedicated to Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, and first published at Florence in 1482 by Antonio di Bartolommeo Miscomini. It was reprinted the following year at Venice by Johannes de Gregoriis (17 May 1483) and by Reynaldus de Novimagio (6 September 1483), and again by Bernardinus Stagninus, de Tridino, in 1486, and by Georgius Arrivabenus, on 4 February 1490/1491. See on its influence Karsten Friis-Jensen, ‘Commentaries on Horace’s “Art of Poetry” in the incunable period’ in Renaissance Studies 9 (1995), pp.228–239; Christoph Pieper, ‘Horatius praeceptor eloquentiae. The Ars poetica in Cristoforo Landino’s commentary’ in Neo-Latin commentaries and the management of knowledge in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period (1400–1700), edited by K.A.E. Enenkel and H. Nellen (Louvain 2013), pp.221–240.

6. Hans-Jörg Künast and Helmut Zäh, Die Bibliothek Konrad Peutingers: Edition der historischen Kataloge und Rekonstruktion der Bestände. Band 1: Die autographen Kataloge Peutingers: Der nicht-juristische Bibliotheksteil (Tübingen 2003); Idem, Band 2: Der juristische Bibliotheksteil (Tübingen 2005); Gesammeltes Gedächtnis: Konrad Peutinger und die kulturelle Überlieferung im 16. Jahrhundert: Begleitpublikation zur Ausstellung der Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg anlässlich des 550. Geburtstags Konrad Peutingers, edited by Reinhard Laube and Helmut Zäh (Lucerne 2016).

7. Helmut Zäh, ‘Konrad Peutingers Exlibris und seine Varianten’ in Gesammeltes Gedächtnis: Konrad Peutinger und die kulturelle Überlieferung im 16. Jahrhundert: Begleitpublikation zur Ausstellung der Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg anlässlich des 550. Geburtstags Konrad Peutingers, edited by Reinhard Laube and Helmut Zäh (Lucerne 2016), pp.82–87. Compare the impressions in the British Museum 1988,0723.13 (link) and 1988,0723.11 (link).

8. Typical forms are ‘Liber Chuonradi Peutinger Augustani vtriusque Iuris Doct.’ (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Inc. fol. 8718; INKA 10002414, link; a book not traced by Künast and Zäh, op. cit.); ‘Liber Chuonradi Peutinger vtriusque iuris Doctoris Co[?]s Maximil a Consilio’ (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. N 1.4.; P–362, link; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 692). See Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, Abb. 3; ii, Abb. 3–4.

9. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, Abb. 7–12, 20–21, 23, 25a-b; ii, Abb. 5–6, 13–14, 16.

10. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, Abb. 26; ii, Abb. 20.

11. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, HSS Clm 4021 b: Index Librorum et Tractatuum Chuonradi Peutinger Augustani Iuris Utriusque Doctoris. Available online via the Munich DigitiZation Center (mdz, link); Stephan Kellner and Annemarie Spethmann, Historische Kataloge der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek München: Münchner Hofbibliothek und andere Provenienzen (Wiesbaden 1996), pp.552–553; Helmut Zäh, ‘Die historischen Kataloge der Bibliothek Konrad Peutingers’ in Gesammeltes Gedächtnis, op. cit., pp.76–81.

12. BSB, Clm 4021 b, f. 53 verso (‘5 Horatius Flaccus cum’, link); f. 75 recto (‘B 5 Horatius’, link); f. 74 verso (‘deficiunt Antiquus Horatius’, link). Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, p.687 no. 707; p.664.

13. BSB, Clm 4021 b: f. 53 verso (‘Horatius ABC–5–6’, link), 86 recto (‘5 Horatius et Euripides’ and ‘6 Horatius et Tibullus’, link). Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, p.704 nos. 750.1 and 751.1; pp.616, 678. The rubric ‘ABC’ is used to signify ‘libelli… in forma minima’.

14. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, HSS Clm 4021 c: Anno Salutis mdxxiii Index denuo emendatus atque restitutus Librorum Chuonradi Peutinger Augustani Juris utriusque Doctoris. Available via mdz (link); Kellner and Spethmann, op. cit., pp.553–554.

15. BSB, Clm 4021 c, f. 102 recto (‘Q Horacii Flacci opera cum commentariis / Antonii Mancinelli / Acronis / Porphirionis / et Christophori cum indice’, link); index entries: f. 2 recto (Acro, link), f. 5 verso (Antoninus Mancinellus, link); f. 40 recto (Porphirio, link). Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, p.395 no. 475. Mancinellus’ edition and commentary was first printed at Venice by Philippus Pincius, for Bernardinus Resina, 28 February 1492/1493; five more editions were printed in folio format at Venice before 1501.

16. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, HSS Clm 4021 d: Conradi Peutinger Senatoris Bibliotheca und was derselben von Kunststucken, Antiquiteten und anderen Sachen incorporiert, inventiert den 28. April 1597 durch David Schwarz Notarius. Available via mdz (link); Kellner and Spethmann, op. cit., pp.554–555; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, pp.39–40. The two folio editions are entered on f. 51 recto (‘34. Opera Horatii.’, link) and f. 39 verso (‘No. 63 Horatius cum Comentarijs’, link), and the two octavos on f. 55 verso (‘No. 60 Horatius et Euripides’ and ‘No. 68 Horatius. et alii’, link).

17. Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, 4° Cod Aug 226: Inventar der Bibliotheken von Konrad, Christoph und Konrad Pius Peutinger. Available via Gateway-Bayern (link); Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, pp.40–41. The two folio editions are entered on f. 52 recto (‘34. Opera Horatii.’, link) and f. 36 recto (‘63. Horatius cum Comentarijs’, link), and the octavo editions on f. 57 verso (‘60. Horatius et Euripides’) and f. 58 recto (‘68. Horatius et alij’, link).

18. Harald Müller and Anne-Katrin Ziesak, ‘Der Augsburger Benediktiner Veit Bild und der Humanismus. Eine Projektskizze’ in Zeitschrift des Historischen Vereins für Schwaben 95 (2002), pp.27–51 (p.41); A.-K. Ziesak, ‘Bild, Veit’ in Deutscher Humanismus 1480–1520: Verfasserlexikon: Band 1 A-K, edited by Franz Josef Worstbrock (Berlin 2005), pp.190–203 (p.198, ‘Gedichte’); Franz Posset, ‘Jack-of-all-trades: Vitus Bild Acropolitanus: monk of Saints Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg’ in Renaissance monks: Monastic humanism in six biographical sketches (Leiden 2005), pp.133–154 (p.137). In 1504, Bild presented his books and manuscripts to his Kloster; a dozen are identified through his donation inscription by Ilona Hubay, Incunabula der Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg (Wiesbaden 1974), p.503; cf. Posset, op. cit., p.138. None is an edition of Horace.

19. Müller and Ziesak, op. cit., p.47, state 1502 as the date of Bild’s initial contact with Peutinger; Posset, op. cit., p.137: ‘His free time he spent with poetry.’

20. Augsburg, Bischöfliches Ordinariatsarchiv, Cod. 81/a-c: ‘Conscriptionis meae pars prima anno 1505 incepta’ (entries in Bild’s own hand until 23 August 1510). See Placidus Ignatius Braun, Notitia historico-literaria de codicibus manuscriptis in Bibliotheca liberi ac imperialis monasterii Ordinis S. Benedicti ad SS. Vdalricum et Afram Augustae extantibus (Augsburg 1781–1796), iv, pp.81–83, no. xiv: ‘Viti Bildii Monachi San-Vlricani scriptorum pars i. in 4to. xvi.’, no. iii (link); Benedikt Kraft, Die Handschriften der Bischöfl. Ordinariatsbibliothek in Augsburg (Augsburg 1934), pp.47 (no. 18), 93; P.O. Kristeller, Iter italicum: accedunt alia itinera: a finding list of uncatalogued or incompletely catalogued humanistic manuscripts of the Renaissance in Italian and other libraries. Volume iii (Alia itinera i): Australia to Germany (London & Leiden 1983), p.459 (locating Bild’s poem to Peutinger on f. 38 verso).

21. Bild’s earliest surviving letter to Peutinger (written on behalf of a fellow monk, Erasmus Huber) is dated 28 August 1509; see Konrad Peutingers Briefwechsel, edited by Erich König (Munich 1923), pp.111–112 no. 65 (link). The correspondence between Bild and Peutinger is dated 1513–1529. Alfred Schröder, ‘Der Humanist Veit Bild, Mönch bei St. Ulrich. Sein Leben und sein Briefwechsel’ in Zeitschrift des Historischen Vereins für Schwaben und Neuburg 20 (1893), pp.173–227 (p.175: ‘Auch an Konrad Peutinger hat damals Bild ein dichterische Bitte gerichtet, nämlich die, Peutinger möge ihm sein Horazexemplar leihen zur Korrektur des einigen.’).

22. On Peutinger’s reading practices and forms of annotation, see Hans-Jörg Künast, ‘Two volumes of Konrad Peutinger in the Beinecke Library’ in The Yale University Library Gazette 77 (2003), pp.133–142; Anthony Grafton, ‘Reading History: Conrad Peutinger and the Chronicle of Nauclerus’ in Gesammeltes Gedächtnis, op. cit., pp.19–26. Useful comparisons can be drawn from Willibald Pirckheimer’s annotations in his copy of the 1490 edition of Landinus’s commentary (Manchester, John Rylands Library, R214338); see Paul White, ‘Reading Horace in 1490s Padua: Willibald Pirckheimer, Joannes Calphurnius and Raphael Regius’ in International Journal of the Classical Tradition 23 (2016), pp.85–107 (link).

23. Folio m1 recto (Liber iii, xxiv, 50): vel scelerum et omnes codices habent. The same hand conjectures on folio i7 recto (Liber iii, xxiv, 4): vel punicum (publicum is accepted by modern editors).

24. The writer has had access to a single sample of Bild’s hand, a page (21 recto) from Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, 2° Cod 207: Sammelhandschrift des Vitus Bild, reproduced by Herrad Spilling, ‘Handschriften des Augsburger Humanistenkreises’ in Renaissance- und Humanistenhandschriften, edited by Johanne Autenrieth (Munich 1988), pp.71–84 Abb. 37. Another possible annotator is Peutinger’s wife, Margarete Welser (1481–1552), whose hand also is insufficiently known by the writer. Cf. Anthony Grafton, ‘Reading History', op. cit., p.19, commenting ‘Collating texts was an everyday activity in the Peutinger household’.

25. Commentationes Ioannis Pici Mirandulae (Bologna: Benedictus Hectoris, 1496). The letter to Giovanni Francesco occupies folios RR3 verso-RR4 verso (excerpt on RR4 recto, link). It is reprinted in all later editions of Pico’s collected works or letters. David Maskell, ‘Robert Gaguin and Thomas More, translators of Pico della Mirandola’ in Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 37 (1975), pp.63–68, prints the letter from the Opera omnia Joannis Pici Mirandulae (Basel 1572–1573), pp.340–343. The excerpted passage occupies lines 81–85 in Maskell’s transcription.

26. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, pp.13–14.

27. Peutingers Briefwechsel, op. cit., letters 44 (dated 1506), 102 (dated 1512). Künast and Zäh, op. cit., record eight of Giovanni Francesco’s publications in Peutinger’s library and three works of Giovanni.

28. Compare the handwritten index by Peutinger (dated at Prozzolo, 1 September 1484) in his copy of Johannes Christophorus Porchus, Lectura super primo, secundo et tertio libro Institutionum cum additionibus Jasonis de Mayno, [Pavia]: Julianus de Zerbo, 11 October 1483 (Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg, 2° Ink 584, reproduced by Künast and Zäh, op. cit., Abb. 20; Hans-Jörg Künast, ‘Porcus statt Porchus: Wie das Schwein auf den Einband kam’ in Gesammeltes Gedächtnis, op. cit., pp.206–209); Peutinger’s manuscript ‘Libellus annotationum’, written at Padua in 1486 (Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg, 4° Cod. Aug. 213/III); and the electronic facsimile of Peutinger’s copy of Marcus Tullius Cicero, Epistulae ad familiares, Venice: [Printer of the 1480 Martialis], 1 July 1480 (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 2 Inc.c.a. 935 a; link).

29. C.E. Wright, ‘Manuscripts of Italian Provenance in the Harleian Collection in the British Museum: their sources, associations and channels of acquisition’ in Cultural Aspects of the Italian Renaissance: Essays in Honour of Paul Oskar Kristeller, edited by Cecil H. Clough (Manchester 1976), pp.462–484 (pp.473–475).

30. Harley Ms 2890: Psalterium, et cantini, ad usum Ecclesiae Augustanae, 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 12th century (link), Harley MS 2908: Augsburg Sacramentary (‘Seeon Sacramentary’), made for the Benedictine abbey of St Ulrich and St Afra, mid-11th century (link), Harley Ms 2941: Missal, region of St Gall, c. 1500 (link).

31. Humphrey Wanley, The Diary of Humfrey Wanley, 1715–1726, edited by Cyril Ernest Wright and Ruth C. Wright (London 1966), i, pp.xlix, 128, 138. Further details of the transaction are in Noel’s account book (British Library, Egerton 3777): transcription by Cyril E. Wright, ‘A “lost” account-book and the Harleian Library’ in The British Museum Quarterly 31 (Autumn 1966), pp.19–24 (p.22). C.E. Wright, Fontes Harleiani: a study of the sources of the Harleian Collection of manuscripts preserved in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum (London 1972), p.275: Mss 3668 (Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 457), 3676 (Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 557), 3685 (Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 558), 3736 (link), 3752 (link), 3753 (link), 4986 (link). Cf. Harleian Mss. 2703 (link) and 2953 (link).

32. Diary of Humfrey Wanley, op. cit., i, pp.141, 143–144: ‘11. Horatius cum Christoph. Landini Interpretationibus. Venet. per Joann. de Forliuio & socios, 1483. fol. min.’. For John Gibson’s supplies of printed books and manuscripts to the Harleys, see C.E. Wright, Fontes Harleiani, op. cit., pp.162-164; Wright, ‘Manuscripts of Italian Provenance’, op. cit., pp.463–468.

33. Howard M. Nixon, ‘A Harleian Binding by Thomas Elliot, 1721’ in The Book Collector 13 (1964), p.194; reprinted in H.M. Nixon, Five centuries of English bookbinding (London 1983), p.136 no. 60. Howard M. Nixon and Mirjam M. Foot, The history of decorated bookbinding in England (Oxford 1992), p.82.

34. Comparable bindings: Plato, Opera, Florence: Laurentius (Francisci) de Alopa, Venetus, [1484–1485] (University of Glasgow Library, Sp. Coll. Hunterian Bf.3.7; link); cf. Gaius Sallustius Crispus, Opera, Florence: Apud Sanctum Jacobum de Ripoli, 1478 (University of Glasgow Library, Sp. Coll. Hunterian, Bw.2.6; link). See also the binding on a copy of Alexander Pope, Works (London 1717), once with Maggs (catalogue 966, item 96; Catalogue 1075, item 135), consigned to Sotheby’s, London, 17 July 2008, lot 102 (link).

35. Howard Nixon, ‘Harleian bindings’ in Studies in the book trade in honour of Graham Pollard, edited by R.W. Hunt, I.G. Philip, R.J. Roberts (Oxford 1975), pl. 14, Elliott roll 3. The roll is used on British Library, Harleian Ms 2686 (Nixon, ‘Harleian bindings’, op. cit., pl. 11, as by Thomas Elliott, 1724); British Library, Harleian Ms 5670 (British Library bookbinding database, image), 3091 (image),

36. Nixon, ‘Harleian bindings’, op. cit., pl. 14, Elliott, no. 5. The roll appears on British Library, Harleian Mss 5559 (image).

37. Nixon, ‘Harleian bindings’, op. cit., pl. 15, Elliott nos. 1a & b, 2, 3a & b, 6, 9.

38. Nixon, ‘Harleian bindings’, op. cit., pl. 15, Elliott nos. 6, 9.

39. Nixon, ‘Harleian bindings’, op. cit., p.182; pl. 14, Elliott, no. 2.

40. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, nos. 371, 389, 422, 433, 491, 596, 770; ii, nos. 803, 827, 828, 860, 869, 939/940, 993.

41. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, nos. 460, 464/1, 725; ii, no. 976. For a book in WLB not recorded by Künast and Zäh, see footnote 8.

42. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, nos. 25, 405, 493.

43. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 102.

44. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 48.

45. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 480.

46. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 686.

47. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 339.

48. Scriptores historiae Augustae, Venice: [Johannes Rubeus Vercellensis and] Bernardinus Rizus, Novariensis, 1 October 1489 (British Library, IB.22631; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 716). For Peutinger manuscripts in the British Library, see footnotes 30–31.

49. Gaius Plinius Secundus, Historia naturalis, Parma: 1476 (Bodleian Library, shelfmark Auct. N. i. 4; Bod-Inc: P–362; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 692); Angelus de Clavasio, Summa angelica de casibus conscientiae, Venice: Georgius Arrivabenus, 9 October 1489 (Bodleian Library, Auct. 6Q 6.57; Bod-Inc: A–289; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., ii, no. 986); Claudius Ptolemaeus, Cosmographia, Rome: Petrus de Turre, 4 November 1490 (Bodleian Library, Gough Gen. Top. 225; Bod-Inc: P–530; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, 698). A manuscript of Paulus Diaconus, ‘Historia Langobardorum’ and Jordanes, ‘De origine Gestarum’, made for Peutinger with some corrections in his hand, is Ms D’Orville 97 (link); cf. ‘A Manuscript belonging to Konrad Peutinger’ in The Bodleian Library Record 6 (August 1960), pp.578–579.

50. Justinianus, Institutiones, Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 27 December 1486 (Houghton Library, Inc 2055 (B) (18.1), link; not traced in Künast and Zäh, op. cit.).

51. Hans-Jörg Künast, ‘Two volumes of Konrad Peutinger’, op. cit., pp.133–142; these books are Libri de re rustica, Venice: Aldus Manutius, May 1514 (Beinecke Library, Rosenthal Collection 138; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 154); Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, Epistolarum libri decem, Venice: Aldus Manutius and Andrea Torresano, November 1508 (Beinecke Library, Gnp54/b5o8; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 761). A third volume from Peutinger’s library is Homerus, Ilias per Laurentium Vallen. in Latinum sermonem traducta foeliciter incipit, Brescia: Baptista Farfengus, for Franciscus Laurinus, 6 September 1497 (Beinecke Library, Zi +7020.4, link; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 400, unlocated).

52. Gregor Reisch, Margarita philosophica, Strassburg: Johann Schott, 1504 (New York Public Library, KB 1504, link; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 17). The volume was collected by James Lenox (1800–1880) and became part of the founding collection of the New York Public Library in 1895. For a volume in the New York Society Library, acquired before 1850 (link), see Grafton, op. cit., pp.19-26.

53. Janus Cornarius, Uniuersae rei medicae, Basel: In Officina Frobeniana, 1534 (Princeton University Library, 2004–1170N, link; not traced in Künast and Zäh, op. cit.). Cf. Princeton University Library Chronicle 66 (2004–2005), pp.241–242. Recent provenance: Antiquariat Helmuth Domizlaff, Munich, 1962 – Reiss & Sohn, Auktion 89, Königstein im Taunus, 6–10 May 2003, lot 1706 – Jonathan A. Hill, New York, 2003.

54. Antonius Gazius, Corona florida medicinae, sive De conservatione sanitatis, Venice: Johannes and Gregorius de Gregoriis, de Forlivio, 20 June 1491 (Huntington Library, 86912, link; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, 424/1, not located). Recent provenance: George D. Smith, Monuments of early printing in Germany, the Low Countries, Italy, France and England, 1460–1500 (New York 1916), p.50 item 75 (link). The 136 incunabula in Smith’s sale catalogue were purchased en bloc in 1916 by Henry E. Huntington (George Sherburn, ‘Huntington Library collections’ in The Huntington Library Bulletin, volume 1, May 1931, pp.45–46).

55. Jean Pélerin, dit Viator, De artificiali perspectiva, Toul: Pierre Jacobi, 1505 (Robin Halwas Limited, List XVII, 2000, link; Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 584)

56. Ammianus Marcellinus, Historiae, libri xiv–xxvi, Rome: Georgius Sachsel and Bartholomaeus Golsch, 7 June 1474 (Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, no. 723, not located). The book was sold by Bonhams, A Selection of Books from the Collection of Richard Hatchwell, London, 6 October 2009, lot 19 (£6240; link); it is now Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München, 2 Inc.c.a. 296 (link).

57. Künast and Zäh, op. cit., i, nos. 355 (‘Jochen Brüning, Berlin’) and 584 (‘Privatbesitz [Paris]’).