Andreas Conerus: an alias of Andreas Konhofer?

Two Germans living in Rome in the years leading up to its Sack in May 1527 by troops of the Emperor Charles V have for many years intrigued historians of art and of science, who have endeavoured vainly to piece together their biographies. Both men are documented in Venice in the years 1506-1508 and both went afterwards to live in Rome. Both were acute mathematicians, possessing profound knowledge of the Greek textual traditions of mathematics and mathematical astronomy. Both had a particular interest in sundials. Both were friends of the Nuremberg humanist Willibald Pirckheimer.

In this post, we adduce evidence to support a credible hypothesis, that “Conerus” is an onomastic Latinisation of “Konhofer,” and that Andreas Conerus and Andreas Konhofer are one man. Appended is an updated list of the known manuscripts and printed books belonging to Andreas Konhofer, alias Andreas Conerus.

Andreas Konhofer

Nothing whatsoever is known about Andreas Konhofer’s parentage. There has been speculation that he stemmed from the burgher family of Nuremberg (Konhofer, Kunhofer, Künhofer, Conhover), whose most prominent member was Konrad Konhofer (1374-1452), a canon lawyer, chaplain and advisor successively to the bishops of Bamberg and Eichstätt, ambassador for the council of the city of Nuremberg at the papal curia in Rome, and afterwards Pfarrherr in the prominent Nuremberg church of Sankt Lorenz. But proof is yet to be forthcoming.

It is presumed that Andreas was a pupil in Nuremberg in 1496 of the humanist schoolmaster Heinrich Grieninger,1 one of five gifted students that Grieninger is known to have funnelled in that year to the university at Ingolstadt, since the Ingolstadt matriculation register records the entry, on 4 November 1496, of “Andreas Künhofer pauper”.2 In February or March 1502, his professor, the mathematician Johannes Stabius (Stöberer; before 1468-1522), moved to the university at Vienna, and Andreas followed him, matriculating on 13 October 1502.3 In 1502, Andreas made calculations of the phases of the moon for an illustrated broadsheet almanac published at Nuremberg,4 and in 1504 he contributed verses for an illustrated pamphlet published by Stabius, the newly-crowned poet laureate.5 About this time he also composed a treatise on sundials (Formularia horologiorum secundum Kunhoffer) for the Nuremberg humanist and astronomer, Bernhard Walther (1430-1504), the intellectual heir of Regiomontanus.6 Andreas Schöner subsequently placed Konhofer next to Regiomontanus among learned scholars on this aspect of mathematics (aliorum doctiorum artiscum de hac Mathematum parte commentationes extare).7 In Georg Tannstetter’s biographical survey of the mathematicians and astronomers who were active in Vienna from 1348 to 1514, Konhofer is identified as a pupil of both Stabius and the eminent Viennese professor of mathematics, Andreas Stiborius (Stöberl; ca 1464-1515), and declared to be “highly respected throughout Italy and especially in the city [Rome] itself, where there are a large number of highly learned men. He will undoubtedly be useful to posterity due to his outstanding abilities.”8

Andreas Konhofer is first documented in Italy in February 1506. He had been awarded a five-year scholarship to enable study at a German or Italian university, on the condition that he enter the church or administrative service of Nuremberg after successfully completing his studies.9 Konhofer chose to enrol in medicine (his alternatives were theology, or law) at the university of Padua.10 He is mentioned in four letters written at Venice by Albrecht Dürer to Willibald Pirckheimer, the humanist and Nuremberg Ratsherr, who was financing Dürer’s trip: 28 February 1506 (My dear friend, Andreas Künhofer asked me to send you his greetings. He plans to write to you by the next courier),11 8 March 1506 (My dear Herr Pirckheimer, Andreas Künhofer sends his good wishes. He will soon write to you to ask you if you could talk to the Council on his behalf and explain why he does not stay at Padua. He says there is nothing there for him to learn anymore), 25 April 1506 (The news has reached me that Andreas Künhofer is gravely ill), 18 August 1506 (PS. Endres [Andreas] is here and sends his regards. He isn’t back to full strength and is short of money, for his long illness and debt have eaten up his reserves. I have lent him 8 ducats myself, but don’t tell anyone, in case he finds out, for he would think I betrayed his confidence. I assure you he behaves so honourably and discreetly, and everyone wishes him well.). This loan of 8 ducats to Kunhofer might be referenced in Durer’s last surviving letter to Pirckheimer from Venice, dated 13 October 1506 (And I am cursed with bad luck. In the last three weeks someone who owed me 8 ducats made a run for it.).12

If Tannstetter’s notice is reliable, Konhofer had arrived in Rome by 1514. He was living on Monte Quirinale in September-October 1517, when he was visited by Johann Cochlaeus (Dobneck; 1479-1552), then touring Italy as tutor to three nephews of Willibald Pirckheimer. It seems that Konhofer was assisting Pirckheimer to complete some text, and in a letter to Pirckheimer, dated 3 October, Cochlaeus reported his receipt from “dominum Andraeam [!] Kunhofer” of some of its missing quires.13 One of Cochlaeus’ charges, Georg Geuder, needed help with his Greek, and the young man informed Pirckheimer on 16 November that “domini Andreae Cunhofer” had recommended a tutor who was giving him daily lessons at home.14

In January 1521, Pirckheimer was denounced as a Lutheran, and named in the bull of excommunication against Luther (Decet Romanum Pontificum, 3 January 1521). Absolution from a charge of heresy was reserved to the Holy See, and it required pressure both in Rome and at the imperial court before Pirckheimer’s name was formally struck from the bull (August 1521). During this process, another of Pirckheimer’s correspondents, Michael von Kaden, wrote to Pirckheimer from Rome (3 March 1521), stating that “domino Andreae Kunhofer” was advising a direct appeal to the Pope.15 A letter to Pirckheimer from an unidentified correspondent in Rome (Johann ?), dated 5 April 1525, refers to “hern Andreas Kunhoffer,” and is the last mention of him in the surviving Pirckheimer correspondence.16 Since the letter preceding is lost, the context is uncertain, however it seems that Konhofer was then involved in diplomatic affairs, and was helping Pirckheimer prepare his new translation of Ptolemy’s Geographike Hyphegesis (Strassburg 1525). How Konhofer was supporting himself is unclear.17 In October 1521, Cochlaeus wrote to the papal nuncio, Girolamo Aleandro, to inform him that (for reasons of security) he was posting his letters either via the Fugger Bank or via “Andream Nurembergensem in cancellariam.”18 If Kunhofer was indeed employed in the papal chancery, his office is not recorded.19

No subsequent references to Andreas Konhofer have been recovered.

Andreas Conerus

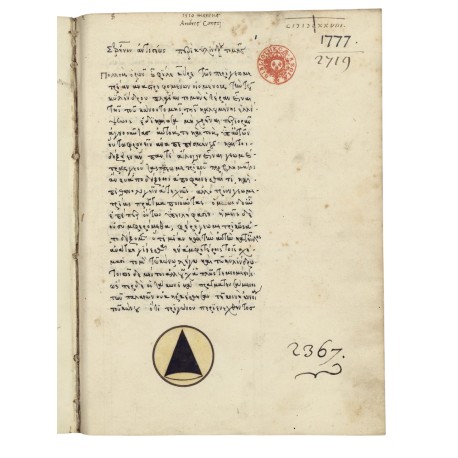

Andreas Conerus is unknown and unheard of before 1507, when he acquired at Venice a 15C manuscript of Euclid’s works on mathematical optics.20 The following year, Conerus acquired five manuscripts containing texts of ancient Greek mathematicians and astronomers. Each manuscript received his purchase inscription, one in the form “1507 Venetijs And. Conerj” (no. 1 in List below), four as “1508 Venetiis Andreae Coneri” (nos. 2-4, 6), and one “Andreae Coneri 1508 Venetiis” (no. 5). In a margin of each manuscript, Conerus drew his personal device, a black cone inscribed on a circular field. A Latin manuscript (no. 6), William of Moerbeke’s autograph of his translation of Archimedean texts, may have been acquired by Conerus from the estate of Bishop Pietro Barozzi (d. 1506/1507). Conerus corrected it against another manuscript, probably the Greek manuscript then in Bessarion’s library.21

Personal device of Andreas Konhofer, alias Andreas Conerus (detail from no. 7 in List below)

How long Conerus remained in Venice is unknown. On 11 August 1508, Luca Pacioli delivered a lecture on Euclid before an audience of 500 in San Bartolomeo, the German church in Venice. Although Conerus is unidentifiable in the roll of listeners,22 a life-long interest in Euclid is manifest. Apart from the manuscript of the Optics and Catoptrics bought in 1507, he acquired (at uncertain dates) two copies of “Euclides Latinus”, and he also possessed Pacioli’s Summa de arithmetica (Venice 1494). If Conerus was in Venice, he surely attended Pacioli’s lecture.

Andrea Conerus in next documented in Mantua, where he inscribed a manuscript “1510 Mantuae. Andreae Coneri” and again drew his device in a lower margin (no. 7). By 1513, he had settled in Rome. On 1 September 1513, Conerus wrote a letter in Italian to the Florentine patrician Bernardo Rucellai, subscribing it “Romae primo Septembris 1513. Tutto di V[ostra] M[agnificencia]. Andreas Conerus”. It concerned a fourth-century stone agricultural calendar in the form of an altar, with a concave sundial for tracking the hours of the day, which was then in the possession of the Della Valle family (the Menologium rusticum Vallense, CIL 6.2306).23 Rucellai apparently wished to make a replica (for the Orti Oricellari?), and Conerus reminds him that it should be of white marble (to show best the shadow of the gnomon) and provides four measured drawings and construction details. In 1515, Conerus acquired a manuscript containing Latin tracts on gauging together with the Sphaera of Menelaus Alexandrinus, which he inscribed twice “1515 Romae. Andreae Coneri” (no. 8). On 2 February 1516, “Andreas Conerus” borrowed from the Vatican Library a manuscript “Euclidis Geometria cum Musica Ptolemei” and returned it on 1 April 1516.24

On 14 May 1527, a week after the troops of Charles V entered Rome, “Andrea Conero” served as a witness to a deed involving the Welser bank,25 and on 9 August 1527, when Johann Fugger deposited precious stones and silverware at the Welser bank before fleeing Rome, “Andrea Conero” witnessed the inventory.26 In two documents of this period, Conerus is linked to Bamberg. In March 1526, he went on a mission to the Bavarian dukes, to deliver a papal brief expressing Pope Clement VII’s pleasure at having received certain assurances from the Bavarian ambassador in Rome, Bonaccorso Grino.27 He used the occasion to present a private request, “Pro Andrea Conero Bambergensi,” an appeal to the Archduke of Austria to intervene in his dispute with the Augustinians of Krems an der Donau over payment of a pension.28 On 20 October 1527, at Ostia, “Andrea Conero c. Bambergen. dioc.” witnessed a document prepared by the notary Jacobus Apocellus (Apozeller, Appenzeller; 1484-1550).29 The abbreviations in Conerus’ attestation were elaborated by Thomas Ashby in 1904 as “clericus Bambergensis diocesis,” and Ashby subsequently referred to Conerus as “a priest”.30 Others have repeated Ashby’s interpretation, referring to Conerus as a cleric,31 or ecclesiastic,32 or priest.33 It is unlikely however that Conerus was ever ordained, more probable that he became canonicus Bambergensis, a secular office, which bestowed an income on its holder. The appeal to the Archduke of Austria in 1526 concerning unpaid stipends in the diocese of Salzburg suggests that Conerus relied heavily on income received from benefices.

Conerus and Apocellus both suffered grievously during the Sack of Rome.34 From mid-July until mid-October 1527, Conerus was wholly dependent on Apocellus, living at his expense at his house in the Strada dei Banchi, near S. Celso, in the Ponte district,35 then at Ostia, except for a brief period of ten days, when Conerus was allowed to board at the Apostolic Palace. Toward the end of October, Conerus moved into the household of Engelhard Sauer, a native of Nuremberg, a relative of Cochlaeus and a correspondent of Pirkheimer, who was Factor in the Roman office of the Fuggers and director of the papal mint.36 There Conerus fell mortally ill and died, probably on 3 November 1527.

It is unclear what testamentary instructions were made by Conerus, if any. A document drawn and notarized by Apocellus on 8 November 152737 identifies Blasius Sweicker (“D. Blasium Schuryker”) as executor of his estate,38 specifies amounts to be reimbursed to those who had cared for Conerus in recent months, and inventories his possessions (almost entirely books). It offers a glimpse of Conerus’ social network and possible clues to his employments. Claimants for compensation (and their witnesses) included Apocellus (notarius auditoris camera, 1520-1534), Johannes de Euskirchen (clericus Treverenis et Coloniensis diocesium; procurator in audientia litterarum contradictarum, 1512-1534) and “Jo. de Ritiis alias Bulgaro” (Clerico Firmanae diocesis), for board and for provisions; and Euskirchen, Quirinus Galler (clericus Pataviensis diocesis; notarius rote 1532-1541), and Hermannus Crol (scriptor archivii Romane curie, 1517-1531), for burial expenses.

The inventory begins with a list of items of clothing left in Sauer’s residence, then of manuscripts and printed books stored in the home of Johannes Sander of Nordhausen (1455-1544), a notary of the Rota (1497-1537), member since 1505 and sometime rector of the Confraternitas D. Mariae de Anima. Sander resided in a house beside S. Maria dell’Anima and both he and his palazzetto had survived the Sack of Rome relatively unscathed.39 Conerus’ books were kept there in two chests. One, locked and iron banded, contained about 40 volumes, all except one (Petrarcha vulgare) in Greek or Latin, including: Aldine editions of Aesop, Dioscorides, and Suetonius; Greek manuscripts of Pappus Alexandrinus, Heronis Alexandrinus, Menelaus Alexandrinus, Claudius Ptolemaeus, Janus Lascaris, and unidentified authors; Latin manuscripts of Archimedes and Bartholomaeus Anglicus; and books on mathematics and astronomy by modern authors, including Regiomontanus and Johann Werner. One manuscript (Hippiatrica of Apsyrtus) was withdrawn after the inventory and given to the Executor. The other trunk (locked only) contained about 60 volumes, of which one (a manuscript of the Almagest of Ptolemaeus) is described in the inventory as having been “trampled under the feet of the mercenaries” (non ligatus, conculcatus pedibus Barbarorum). All the texts in this trunk were in Greek or Latin, with Latin predominating. A vellum manuscript of the treatise on surgery of Albucasis was taken by the Executor.

The Executor then inventoried possessions which Conerus had left behind in the Apostolic Palace.40 The books here were presumably Conerus’ reading matter during the ten days he boarded within its walls: two volumes of Homerus, two of Horatius Flaccus (one “in littera Aldi”), two of Publius Ovidius Naso (a vellum manuscript of the Metamorphoses and the Epistulae Heroidum), and Tibullus. Also present was a collection of the Epigrammata greca, which the notary Apocellus took for himself (Et ego notarius habui collectanea ipsius in Epig. greca).41 Apart from “Acta Concilii Constantiensis” and a book by Cochlaeus (“Quaedam Io. Coclaei scripta”), no theological works were present at either location, which casts further doubt on the suggestion that Conerus had taken holy orders.

list of manuscripts and printed books

Ten manuscripts and two printed books bearing Andreas Conerus’ ownership marks are known. Eight manuscripts have his inscription dated at Venice 1507 and 1508, Mantua 1510, and Rome 1515, accompanied by his conventional device of a cone within a circle. Two manuscripts retain the device only. The two printed books, copies of the 1501 Aldine edition of Juvenal and Persius and the 1501 Aldine edition of Martialis, have the same, undated presentation inscription to Willibald Pirckheimer: “Bilibaldo Pirkamer Andreas Coneriis D[ono]. D[edit].”42 Unfortunately, both volumes were rebound by Francis Bedford in the 19C, and any clues to where and when the books were first bound or gifted are long lost.

Our supposition is that Andreas Konhofer latinised his surname soon after his arrival at Venice, in 1506 or 1507. He and Pirckheimer were in intermittent contact from then until at least 1525. Opportune moments for making these two gifts occurred ca 1506-1508 and ca 1517. In the earlier period, Konhofer was doubtless anxious to appease Pirckheimer, for abandoning his course of study at Padua, and reneging on his obligation to the Nürnberger Rat. Around 1517, his contact with Pirckheimer seems to have been renewed through the visit of Cochlaeus and Pirckheimer’s nephews, Hans, Sebastian and Georg Geuder. One of the latter, Georg Geuder, sent to Pirckheimer from Rome in 1517 a large parcel of books. It may be that the Juvenal and Martialis were added by Conerus to that shipment.

Absent from the List below is an album of drawings of ancient and Renaissance buildings known as the Codex Coner. It was assembled in 1630s by the Roman antiquarian Cassiano Dal Pozzo, who placed within it a copy of Conerus’ letter of 1513 (see above) about the Della Valle sundial and calendar (the original letter was in Dal Pozzo’s archive). The drawings passed afterwards into the Albani Library, when they were remounted in a vellum binding inscribed along its spine “Architect / Civilis / Andrea / Coneri / Antiqua / Monume / Rome”. In 1762, the architect James Adam acquired on behalf of King George III the greater part of the Dal Pozzo-Albani collection. Adam retained this album however for his own collection, and it appeared on the market in 1818, when it was acquired by Sir John Soane for his Museum. About 1901, the Soane Museum curator, George Birch, communicated details of it to Thomas Ashby, director of the British School at Rome. Ashby quickly published the aforementioned study, in which he attributes the earlier drawings in the album to Conerus, and gathers together everything he could learn about Andreas Conerus himself.43 By 1913, Ashby and others had rejected Conerus as the draughtsman, and downgraded him to owner of the album. Although subsequent scholarship has now completely disassociated Conerus from the album - it is almost certain that Conerus never owned it, and probably did not even know of it - it nonetheless is invariably referred to as the Codex Coner.44

manuscripts

(1) Euclides, catoptrica; optica; Euclidis isagoge harmonica; copyist Michaēl Damaskēnos (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, inscription “1507 Venetijs And. Conerj” and conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 1r)

● Lattanzio Tolomei (1487-1543)

● Maurice Bressieu (1546-ca 1617)

● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Supplément grec 195 (opac, [link]; digitised, [link])

selective literature

Paul Canart, “Démétrius Damilas, alias le ‘Librarius Florentinus’” in Rivista di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici 14-16 (1977-1979), pp.282-347 (p.312 [link])

(2) Texts by Theodosius Tripolita, Autolycus Pitanaeus, Aristarchus Samius astronomus, Hypsicles; copyists Michaēl Damaskēnos, Janus Lascaris (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, inscription “1508 Venetiis Andreae Coneri” and conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 1r)

● Cardinal Niccolò Ridolfi (1501-1550)

● Catherine de Médicis (1519-1589), integrated into the Bibliotheque royale in 1594

● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Grec 2364 (digitised, [link])

selective literature

Anthony Hobson, “Two Roman bindings” in The Bodleian Library Record 15 (1996), pp.372-376 no. 8 (pp.374, 376, as a Roman binding)

Davide Muratore, La biblioteca del cardinale Niccolò Ridolfi (Alessandria 2009), I, pp.208-209

(3) Texts by Heron Alexandrinus, Iohannes Pothus Pediasimus, Didymus mathematicus, Iulianus Laodicensis, and unknown authors; ca 1494-1503 (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, inscription “1508 Venetijs Andreae Conerj” and conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 1r)

● probably 1527 post-mortem inventory entry “Polygonorum mensuration” [see Mercati, op. cit. 1926, p.142; Claggett, op. cit., III, p.528]

● Lattanzio Tolomei (1487-1543), monogram (f. 95v)

● Marzio Milesio Sarazani (ca 1570-1633/1637), inscription “Martii Milesii Sarazanii” (f. 1)

● Convento di San Silvestro al Quirinale, inkstamp (f. 2 r)

● Giovan Francesco de Rossi (1796-1854), his bequest in 1855 to

● Jesuit College, Vienna-Lainz, transferred to Rome in 1922

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ross. gr. 897 (digitised, [link])

selective literature

Eduard Gollob, Die griechische Literatur in den Handschriften der Rossiana in Wien (Vienna 1910), pp.93-101

Mercati, op. cit. 1926, pp.141-142

Olivier Defaux, La Table des rois: Contribution à l’histoire textuelle des ‘Tables faciles’ de Ptolémée (Berlin 2023), pp.61-62 no. 9 [link]

(4) Texts by Nicomachus Gerasenus mathematicus, Iohannes Philoponus, Nicephorus Gregoras, Isaac Argyrus; anonymous copyist(s), ca 1451-1575 (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, inscription “1508 Venetijs Andreae Conerj” and conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 1r)

● Guido Ascanio Sforza (1518-1564), Biblioteca Sforziana, Rome; his catalogue by Leone Allacci (Vat. Ott. lat. 2355), 142 CXII

● Cardinal Domenico Passionei (1682-1761); Inventario dei libri della biblioteca Passionei (Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, Parm. 878), p.464 (“Philoponus in arithmeticam et Argyrus monachus in eodem graece 4°”)

● Rome, Biblioteca Angelica, gr. 001 (formerly C. 3. 18) (digitised, [link])

selective literature

Thomas William Allen, Notes on Greek Manuscripts in Italian Libraries (London 1890), p.43 no. 44 [link]

(5) Texts by Iohannes Philoponus, Proclus Diadochus, Theon Alexandrinus, Claudius Ptolemaeus (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, inscription “Andreae Conerj 1508 Venetijs” and conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 1r)

● Lattanzio Tolomei (1487-1543)

● Cardinal Ridolfi (1501-1550), inscription of his librarian Matteo Devaris

● Pietro Strozzi (1510-1558)

● Catherine de Médicis (1519-1589), integrated into the Bibliothèque royale in 1594

● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Grec 2497 (digitised, [link])

selective literature

Anthony Hobson, “Two early sixteenth-century binder’s shops in Rome” in De libris compactis miscellanea (Studia Bibliothecae Wittockianae, 1) (Aubel 1984), pp.79-98 (p.90 no. 3 as Cardinals’ Shop binding)

Muratore, op. cit., I, p.183; II, p.209

Defaux, op. cit., pp.52-55 no. 5 [link]

(6) Composite manuscript made of three parts: (a) ff. 1r-7v: Anthologia Graeca Planudea, edited by Janus Lascaris (Florence: Laurentius Francisci de Alopa, 11 August 1494); (b) ff. 8r-64v: texts written by a single hand, that of William of Moerbeke, dated February to 31 December 1269: Alhazen, De speculis comburentibus; De ponderibus Archimenidis; Archimedes’s scientific works in William of Moerbeke’s translation; Heron of Alexandria, Catoptrica; Claudii Ptolemei de speculis… Explicit liber Ptolomei de speculis; Ptolemaica; (c) ff. 65r-75r: Johannes Peckham, Perspectiva communis, incomplete, in a 14C hand

selective provenance

● possibly Pietro Barozzi, bishop of Padua (1441-1506/1507) (?) [see Clagett, op. cit., III, pp.479, 527]

● Andreas Conerus, inscription “1508 Venetijs, Andreae Coneri” (f. 7 bis recto), table of contents (f. 7 bis verso), conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 8 r)

● probably 1527 post-mortem inventory entry “Archimedes grecus scriptus … cum fragmentis” [Clagett, op. cit., III, p.535]

● Marcello Cervini (future pope Marcellus II; 1501-1555)

● Giovanni Angelo d’Altemps, II duca di Gallese (1587-1620), inscription (f. I recto) “Ex codicibus Ioannis Angeli ducis ab Altaemps”

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ott. lat. 1850 (digitised, [link])

selective literature

Codici latini datati della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, I: Nei fondi archivio S. Pietro, Barberini, Boncompagni, Borghese, Borgia, Capponi, Chigi, Ferrajoli, Ottoboni (Vatican City 1997), pp.175-176 no. 398

(7) Texts by Serenus Antinoensis; copyist Michaēl Damaskēnos (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, inscription “1510 Mantuae. Andreae Coneri” and conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 1 r)

● Franciscus Attaris Cyprius [“Note de don en latin à Janus Lascaris” (Pinakes)]

● Janus Lascaris (1445-1534)

● Cardinal Niccolò Ridolfi (1501-1550)

● Catherine de Médicis (1519-1589), integrated into the Bibliothèque royale in 1594

● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Grec 2367 (digitised, [link])

selective literature

Mercati, op. cit. 1926, p.141

Tura, op. cit., p.707

Muratore, op. cit., I, p.208

(8) Texts by Georg von Peuerbach, Gregorii [!] Purbachii … ad Joh. ep. Voragnomonis [!]Canones de compositione et usu gnomonis geometrici (ff. 2r-14v); collection of Latin tracts on gauging (ars visoria) (ff. 17r-57r), and Spherics of Menelao (ff. 64r-129v)

selective provenance

● Andreas Conernus, inscriptions “1515 Romae. Andreae Coneri” (ff. 1r, 17r)

● probably 1527 post-mortem inventory entries “Menelaus grecus scriptus” and “Canones Astrolabii latini scripti” [see Mercati, op. cit. 1952, pp.144-145; Tura, op. cit., p.706]

● Perugia, Biblioteca dell’Archivio storico del Monastero di San Pietro, CM 18

selective literature

Regesto in transunto dell’Archivio di S. Pietro in Perugia (Perugia 1902), p.81

(9) Texts by Euclides, Nicomachus Gerasenus mathematicus, Gregorius Nazianzenus; copyists Grēgorios hieromonachos, Michaēl Rōsaitos (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 124r)

● Marcello Cervini (future pope Marcellus II; 1501-1555)

● Gugliemo Sirleto (1514-1585)

● Giovanni Angelo d’Altemps, II duca di Gallese (1587-1620)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ott. gr. 310 (digitised, [link])

(10) Texts by Theodosius Tripolita, Autolycus Pitanaeus, Eutocius Ascalonita; copyist Zacharias Kalliergēs (Pinakes, [link])

selective provenance

● Andreas Conerus, conventional device of a cone within a circle (f. 1r)

● Lattanzio Tolomei (1487-1543)

● Filippo Tolomei, inscription “Mauritij Bressij / Ex dono illustris viri Philippi Ptolomaei equitis S. Stephani / Senensis / Senis 1 Deceb. 1589” on endleaf

● Maurice Bressieu (1546-ca 1617)

● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Supplément grec 451 (digitised, [link])

selective literature

Canart, op. cit., p.312

Maria Luisa Agati & Paul Canart, “Copie et reliure dans la Rome des premières décennies du XVIe siècle, Autour du Cardinal’s shop” in Scripta 2 (2009), pp.9-38 (p.38)

printed books

(1) Decimus Junius Iuvenalis & and Aulus Persius Flaccus, Iuuenalis. Persius (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, August 1501)

provenance

● Andreas Conerus, presentation inscription, “Bilibaldo Pirkamer Andreas Coneriis D.D.”

● Willibald Pirckheimer (1470-1530)

● Willibald Imhoff (1518-1580)

● Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel (1585-1646)

● Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk (1628-1684)

● Royal Society of London, inkstamp

● Bernard Quaritch, London

● Henry Huth (1815-1878)

● Alfred Henry Huth (1850-1910), exlibris “Ex Mvsaeo Hvthii”

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the famous library of printed books, illuminated manuscripts, autograph letters and engravings collected by Henry Huth, and since maintained and augmented by his son Alfred H. Huth, Fosbury Manor, Wiltshire; the printed books and illuminated manuscripts. Fourth portion, London, 7-10 July 1914, lot 4126 (“From the library of Bilibald Pirckheimer. On the title is written: ‘Bilibaldo Pirkamer Andreas Conetus [sic]; D.D.’ Stamp of the Royal Society (Howard Gift) on back of title”) [link]

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£17) [link]

● Georges Heilbrun, Paris; their Catalogue 36 (1971), item 20 (“Exemplaire de Wilibald Pirkheimer offert par Andrea Coner qui parait s’identifier avec un dessinateur et architecte.”)

literature

Bibliotheca Norfolciana: sive catalogus libb. manuscriptorum & impressorum in omni arte & lingua (London 1681), p.68 (Juvenalis … ibid. 1501” [link])

W.C. Hazlitt & F.S. Ellis, The Huth Library. A catalogue of the printed books (London 1880), III, p.793 (“From the library of Bilibald Pirckheimer. On the title is written ‘Bilibaldo Pirkamer Andreas Conetus. D.D.’” [link])

Tura, op. cit., pp.707-708 (“nota autografa ‘Bilibaldo Pirkamer Andreas Conerus D.D.’: si ha così documento di un rapporto, non testimoniato altrimenti, tra Coner e Pirckheimer”; il Giovenale poi (oggi in una raccolta privata) conserva … la prima traccia pervenutaci della bellissima scrittura del Coner, e la prima notizia che lo concerne.”)

Muratore, op. cit., I, p.184

(2) Marcus Valerius Martialis, Martialis (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, December 1501)

provenance

● Andreas Conerus, presentation inscription, “Bilibaldo Pirkamer Andreas Coneriis D.D.”

● Willibald Pirckheimer (1470-1530), portrait-exlibris by Albrecht Dürer, lettered “Bilibaldi Pirkeymheri effigies aetatis suae anno LIII, vivitur ingenio caetera mortis erunt. MDXXIV” with the artist’s monogram; second exlibris lettered “Spes Tribvlatio Invidia Tolerantia 15.I.B.29” by the Monogrammist J.B. (possibly Georg Pencz) [Ilse O’Dell, Deutsche und Österreichische Exlibris 1500-1599 im Department of Prints and Drawings im Britischen Museum (London 2003), no. 301, no. 300]

● Willibald Imhoff (1518-1580)

● Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel (1585-1646)

● Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk (1628-1684)

● Royal Society of London, inkstamp

● Bernard Quaritch, London; their A General catalogue of books, offered to the public at fixed prices (London 1874), p.1425 item 17907 (“with presentation inscription to Pirckheimer by Andreas Conerus, a very fine copy in red morocco, edges gilt and goffered, with the portrait and bookplate of Pirckheimer, £10 10s”) [the General Catalogue was issued in sections, with this section first circulated as Catalogue 291: Bibliotheca xylographica, typographica et palaeographica: Catalogue of block books and of early productions of the printing press in all countries, and a supplement of manuscripts (London October 1873), item 17907 [link])

● Henry Huth (1815-1878)

● Alfred Henry Huth (1850-1910), exlibris “Ex Mvsaeo Hvthii”

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the famous library of printed books, illuminated manuscripts, autograph letters and engravings collected by Henry Huth, and since maintained and augmented by his son, Alfred H. Huth, Fosbury Manor, Wiltshire; the printed books and illuminated manuscripts. Fifth portion, London, 4-7 July 1916, lot 4752

● George D. Smith, New York - bought in sale (£12) [Book Auction Records, 13, p.492]

● The Rosenbach Company, Five hundred rare books, manuscripts and autograph letters (Philadelphia 1936), item 312 ($360; “The fifth book printed in italic letter. An extremely interesting copy presented by Pirckheimer to a friend, with his autograph inscription on the title, ‘Bilibaldo Pirkamer; Andreas Corneriis D[ono] D[edit].’ Inserted as a frontispiece is his portrait engraved by Durer, and at the end his famous woodcut book plate by the Master of the Monogram J.B. The Howard copy, with the duplicate stamp of the Royal Society” [link])

● Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco, Catalogue 93 (Turin 2006), item 336 [link]

● Libreria Philobiblon, Mille anni di bibliofilia dal X al XX secolo (Rome & Milan 2008), item 59 [link]

● PrPh Rare Books, New York

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased from the above, 2012 [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0054]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection, D-M, New York, 18 October 2024, lot 969 ($19,050; catalogue online, [link]) [RBH N11499-969]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Bibliotheca Norfolciana: Sive catalogus libb. manuscriptorum & impressorum in omni arte & lingua (London 1681), p.78 (“Martialis … octavo. Venet. 1501” [link])

Catalogue of the library of the Royal Society (London 1825), p.367 [link]

Catalogue of miscellaneous literature in the library of the Royal Society (London 1841), p.163 [link]

W.C. Hazlitt & F.S. Ellis, The Huth Library. A catalogue of the printed books (London 1880), III, p.914 (“On the title is inscribed ‘Bilibaldo Pirkamer Andreas Coneriis. D.D.’“ [link]

Emil Offenbacher, “La bibliothèque de Wilibald Pirckheimer’ in La Bibliofilía 40 (1938), pp.241-263 (“Liste de livres provenant de la Bibliothèque de Wilibald Pirckheimer”, p.254: “Avec dédicace autographe d’Andr. Conerus à Pirckheimer” [link])

Tura, op. cit., pp.707-708

Muratore, op. cit., I, p.184

1. Gustav Bauch, “Die Nürnberger Poetenschule 1496-1509” in Mitteilungen des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Nürnberg 14 (1901), pp.1-64 (p.13 [link]), referring to a letter from Grieninger to Konrad Celtes, 4 October 1496 (Der Briefwechsel des Konrad Celtis, edited by Hans Rupprich, Munich 1934, pp.212-213 no. 130), which mentions other students, but not Konhofer.

2. Götz von Pölnitz, Die Matrikel der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Ingolstadt-Landshut-München. Teil I: Ingolstadt, Band 1: 1472-1600 (Munich 1937) p.255. A registrant categorized as “pauper” was not necessarily destitute; rather, the label indicated that his family came from the lower layers of the bourgeoisie, were artisans, or unskilled laborers.

3. Die Matrikel der Universität Wien, Band 2: 1451-1518, edited by Franz Gall & Willy Szaivert (Graz 1967), p.305 (“Nacio Reuensium, Andreas Künhofer ex Nurnberga”).

4. The only recorded copy is defective, with a few words of the publication line torn away: Geprackticirt In der loblichen vniuersitet ingo [defective; Ingolstadt per Andre] am kunhofer von Nurmberg. See Josef H. Biller, Calendaria Bambergensia: Bamberger Einblattkalender des 15. bis 19. Jahrhunderts von der Inkunabelzeit bis zur Säkularisation (Weissenhorn 2018), PK1 (Staatsbibliothek, 22/VI F 78); Digitale Sammlungen der Staatsbibliothek Bamberg, [image]). Ernst Zinner, Geschichte und Bibliographie der astronomischen Literatur in Deutschland zur Zeit der Renaissance (Leipzig 1941), p.136 no. 812 (“Alle Zeitangaben sind um 15 Min. größer als in Regiomontans Kalender.”).

5. Johannes Stabius, Figura Labyrinthi ([Nuremberg: Wolfgang Huber, ca 1504], woodcuts and verses by Sebastianus Calcidius des Basilisco, Joannes Stabius Austriacus, and Andreas Kunhofer Nurmbergensis (Qui vacuus monstris / labyrinthi tutus in omnes …). See Edmund Braun, “Eine Nürnberger Labyrinthdarstellung aus dem Anfange des 16. Jahrhunderts” in Mitteilungen aus dem Germanischen Nationalmuseum (1896) pp.91-96 [link].

6. The text was contained in a collection “Ad faciendum horologia” which is now lost; see Ernst Zinner, Leben und Wirken des Johannes Müller von Königsberg genannt Regiomontanus (Munich 1938), p.266 no. 292.

7. Andreas Schöner, Gnomonice Andreae Schoneri Noribergensis, hoc est, De descriptionibvs horologiorvm sciotericorvm omnis generis, proiectionibus circulorum sphaericorum ad superficies, cum planas, tum conuexas concauasq[ue], sphaericas, cylindricas, ac conicas, item delineationibus quadrantum, annulorum, &c. libri tres (Nuremberg: Johann Vom Berg & Ulrich Neuber, 1562), f. A3 verso [link].

8. G. Tannstetter, “Viri mathematici quos inclytum Viennense gymnasium ordine celebres habuit,” published with the Tabulae eclypsium magistri Georgij Peurbachii (Vienna 1514), f. aa6 recto: “Andreas Kvenhofer Ex Nuernnberga sub preceptoribus nostris D. Stabio & Stiborio Viennae in Cosmographia et tota Mathematica adeo profecit: ut per totam Italiam: et precipue in urbe ipsa ubi doctissimorum uirorum copia est, praeclarus habeatur. Nec dubium posteritati excellenti suo ingenio profuturus sit,” followed by verses: “Joannes Mihaelis Budorensis Ad excellentem Mathematicum Andream Kuenhoffer Neurbergensem Amicum suum.” [link].

9. This commitment, known as a “Revers,” is dated 30 March 1505; see Nuremberg, Stadtsarchiv, A1 Nr 1505 (“Andreas Kunhofer reversiert sich gegen den Rat zu Nürnberg, welcher ihm das Kunhoferische Stipendium … verliehen hat.” [link]). The annual stipend of 50 fl. was paid by the Konhofer’sche Stiftung, a foundation established in 1445 by Konrad Konhofer; see Bernhard Ebneth, Stipendienstiftungen in Nürnberg. Eine historische Studie zum Funktionszusammenhang der Ausbildungsförderung für Studenten am Beispiel einer Großstadt (15.-20. Jahrhundert), Nürnberger Werkstücke zur Stadt- und Landesgeschichte, Bd. 52 (Nuremberg 1994), pp.103-106, 232-242, 486 (p.241, describing Andreas as “ein entfernter Verwandter des Stifters [Konrad Konhofer]”).

10. Ebneth, op. cit., p.241. Andreas cannot be traced in the Acta graduum academicorum Gymnasii Patavini: ab anno 1501 ad annum 1525, edited by Elda Martellozzo Forin (Padua 1969).

11. Translations by Cristina Neagu, from Early Modern Letters Online (EMLO) [link]. Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, I, edited by Emil Reicke (Munich 1940), nos. 101, 104, 111, 118.

12. Compare Reicke, op. cit., I, no. 129, who rejects speculation that the debtor might be Konhofer; Paul Kalkoff, “Zur Lebensgeschichte Albrecht Dürers, Dürer’s Flucht vor der Niederländischen Inquisition und Anderes” in Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft 20 (1897), pp.443-462 (pp.444-445 [link]).

13. Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, III, edited by Helga Scheible (Munich 1989), p.190 no. 475 (“quaterniones aliquot accepi iussus, ut posteriores simul cum primo folio tibi transmittam, tuque rescribas, quantum tibi desit, ut reliquum quoque recipias”).

14. Scheible, op. cit., III, p.219 no. 488.

15. Scheible, op. cit., IV (Munich 1997), pp.469-470 no. 749.

16. Scheible, op. cit., V (Munich 2001), pp.366-368 no. 923 (“Namhafter, weyser her, vergangen tag ist mir eur weyshaitt schreyben, datum den ersten tag Februari, worden mit samptt euer eingeschlossener zettel, betreffen des cardinals legaten handlungen, er daraus treybt. Hab die als baldt hern Andreas Kunhoffer laut eurs schreibens behendiget, auch den abtruck Ptolomey der gleichen uberantwurt oder die spera. Dorauff schreybt er hiemit hern Iorgen Harttman sein gut geduncken.Versich mich, werdt auch dornebn seinen gutten will vernemen, er gegen euch und seinen frainden hatt etc.”)

17. He cannot be identified in transcriptions of the 1517 and 1527 Roman censuses; cf. Egmont Lee, Habitatores in Urbe: the population of Renaissance Rome (Rome 2006), Claudio De Dominicis, Indice del censimento di Roma del 1518 (online [link]).

18. Walter Friedensburg, “Beiträge zum Briefwechsel der katholischen Gelehrten Deutschlands im Reformationszeitalter. Aus italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken” in Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 18 (1898), pp.106-131 (p.121 [link]).

19. Kalkoff, op. cit., p.445 [link]. Konhofer is not traced in the Repertorium Officiorum Romane Curie (RORC) database [link].

20. Johan L. Heiberg, Euclidis opera omnia, VII: Euclidis Optica, opticorum recensio Theonis, Catoptrica, cum scholiis antiquis (Leipzig 1895), p.xvii no. 13 [link].

21. Marshall Clagett, Archimedes in the Middle Ages, III: The fate of the Medieval Archimedes, 1300-1565 (Philadelphia 1978), p.535 (“It is clear that Coner was no mere passive owner of MS O, for there are many evidences of his correction of the text, and he often erased and redrew William’s crude figures, particularly those which included conic sections. … We cannot be certain when Coner made his corrections. I am inclined to believe that he made them sometime between 1508, when he acquired the codex in Venice, and 1513, when he appears in Rome. At least, as we shall see, there is evidence that he consulted Greek manuscript E (Bessarion’s copy). That manuscript was then at the San Marco library in Venice and would thus have been handy for him if he were working on Manuscript O at Venice.” On p.537 Clagett adduces “indisputable evidence that [Coner] had consulted Greek manuscript E at Venice”).

22. Ninety-four attendees are listed in the preface to the fifth book of Pacioli’s “restoration” of Euclid’s Elements (Venice: Paganino Paganini & Alessandro Paganini, 11 June 1509; colophon 22 May 1509), f. 31 [link]; see Gino Benzoni, “Venezia 11 agosto 1508: mille orecchie per Luca Pacioli” in Studi veneziani 69 (2014), pp.59-324.

23. The original letter came into the possession of the Roman antiquarian Cassiano Dal Pozzo (1588-1657), who caused a copy of it to be written opposite a measured drawing of the sundial (Horilogium solis anticum) in an album that he was assembling of drawings of ancient and Renaissance buildings (known as the Codex Coner, now London, Sir John Soane’s Museum, vol. 115; see below). Other copies of the letter are located by Giovanni Mercati, Scritti d’Isidoro, il cardinale ruteno, e codici a lui appartenuti che si conservano nella Biblioteca apostolica vaticana (Rome 1926), p.141; the original, in the Dal Pozzo archive in Naples, is illustrated by Arnold Nesselrath, “Codex Coner - 85 years on” in Cassiano dal Pozzo’s Paper Museum 2 (1992), pp.145-167 (pp.162-163). The Soane Museum copy (only) is listed by Rita Maria Comanducci, Il carteggio di Bernardo Rucellai: inventario (Florence 1996), p.62 no. 1024.

24. Mercati, op. cit. 1926, p.141 (“Ego Andreas Conerus accepi mutuo a domino Phedro bibliotecario et custodibus domino Laurentio Parmenione et domino Romulo Mammacino Euclidis Geometriam cum Musica Ptolemei, librum ligatum in nigro scriptum in carta bombacina pro quo reliqui vas argenteum, die secunda februarii anno Domini 1516. Idem Andreas Conerus manu propria. - Restituit die prima aprilis 1516.”); Maria Bertòla, I Due primi registri di prestito della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Codici vaticani latini 3964, 3966 (Rome 1942), pp.43-44. Mercati identifies the manuscript borrowed by Conerus as Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. gr. 192; Bertòla believes it to be Vat. gr. 196. Compare Clagett, op. cit., III, p.529, averring that the entry is in Conerus’ hand.

25. G. Cavaletti-Rondini, “Nuovi documenti sul sacco di Roma del MDXXVII” in Studi e documenti di storia e diritto: pubblicazione periodica dell’Accademia di Conferenze Storico-Giuridiche 5 (1884), pp.221-246 (p.237: “Magister Antonius Schedel Phisicus confessus fuit habuisse mutuo a Guillermo ducatos decem auri camere ad Julios x solvendos ad omne beneplacitum. et promisit pro rata comunicare in expensis Custodis. presentibus Andrea Conero et Theodorico [Vafro] [link]). On this and other transactions of the Welser Bank while the imperial army remained in Rome, see Aloys Schulte, Die Fugger in Rom, 1495-1523: mit Studien zur Geschichte des kirchlichen Finanzwesens jener Zeit (Leipzig 1904), p.238.

26. Cavaletti-Rondini, op. cit., pp.242-246 (“Inuentarum bonarum ex domo D. Bartholomei Welseri et sociorum exportatorum ad Fuggaros factum per me Iacobum Apocellum Curiae causarum Camere apostolice Notarium per Petrum Klehletter civem Argentinensem familiarem eorumdem in domo fuggarorum presentibus d. Baldasare Olgiate et Andrea Conero testibus” [link]); Schulte, op. cit., p.238.

27. Monumenta saeculi XVI. Historiam illustrantia, Volumen I: Clementis VII. Epistolae per Sadoletum scriptae: quibus accedunt variorum ad Papam et alios epistolae, edited by Pietro Balau (Innsbruck 1885), pp.222-223 no. 172 (“Datum Romae die viii. Martii. mdxxvi. Anno tertio” [link]).

28. Balau, op. cit., p.223 (“Praeposito et capitulo Chremensi. Pro Andrea Conero Bambergensi. Die ix. Martii mdxxvi. … Pro Andrea Conero controversiam habente cum praeposito et capitulo ecclesiae Chremensis ord.is S. Augustini, super quadam pensione pro concordia parrochialis ecclesiae in Brating Saltzeburgensis diocesis. Die et anno ut supra [9 March 1526]”). Compare the review of Balau in Historische Zeitschrift 56 (1886), pp.526-527, the reviewer commenting “Ich habe die Breven, welche sich im Münchner Hausarchiv finden, nachgeprüft. Unter dem 9. März 1526 ist eine Beglaubigung ausgestellt für den Bamberger Kleriker Andreas Coner, der zu den Bairischen Herzogen in wichtigem Auftrage abgeht; daneben wird derselbe auch eine private Bitte vortragen. Bei B. S. 223 stehen nur einige Breven verzeichnet, welche sich auf Coner’s private Pfunden Angelegenheit beziehen; niemand kann vermuthen, daß Coner auch andere Aufträge hatte. Das Breve vom vorhergehenden Tage, S. 222, an die Baierischen Herzoge nahm Coner mit, es enthält Phrasen über das Entzückten des Papstes wegen der Eröffnungen, die ihm der Baierische Gesandte Bonacorsi Grin gemacht hatte. Uber dessen Verrichtung erfahren wir nichts, nicht einmal das Breve, welches er bei der Ruckreise von Rome erhielt, wird erwähnt.” [link]).

29. “Actum Hostie in palacio episcopali presentibus d. Hermanno Crol scriptore Archivii et Andrea Conero c. Bambergen. dioc. testibus” (Archivio di Stato di Roma, Notari del Tribunale dell’Auditor Camerae, off. 2°, vol. 414, c.145).

30. Thomas Ashby, “Sixteenth-century drawings of Roman buildings attributed to Andreas Coner” in Papers of the British School at Rome 2 (1904), pp.1-88 (p.4); T. Ashby, “Addenda and Corrigenda to Sixteenth Century Drawings of Roman Buildings attributed to Andreas Coner” in Papers of the British School at Rome 6 (1913), pp.184-210 (p.189). See also Giovanni Mercati, “A proposito di Andrea Coner e degli schizzi di edifici di Roma contenuti nel codice Soane” in Note per la storia di alcune biblioteche Romane nei secoli XVI-XIX (Vatican 1952), pp.131-146 (pp.136-137); Clagett, op. cit., III, p.529.

31. Mercati, op. cit. 1926, p.141 (“chierico di Bamberga”); Clagett, op. cit., III, p.527 (“a cleric of the diocese of Bamberg”).

32. Adolfo Tura, “Codici di matematica di Fra Giocondo” in Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 61 (1999), pp.701-711 (p.706 “questo ecclesiastico di Bamberga”).

33. Anthony Hobson, “Jacobus Apocellus” in Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 7 (1979), pp.279-283 (p.279 “a priest from Bamberg”); William J. Sheehan, Bibliothecae apostolicae vaticanae incunabula (Vatican 1997), I, p.xxv (“Coner was a German priest and architect of considerable learning from the diocese of Bamberg”).

34. The residence of Apocellus was ransacked by mercenaries, several of his servants were killed, and Apocellus himself twice robbed; see Johann Mayerhofer, “Zwei Briefe aus Rom aus dem Jahre 1527. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des ‘Sacco di Roma’” in Historisches Jahrbuch 12 (1891), pp.747-756 (pp.753-756 [link]).

35. Before the Sack, there were 10 in his household, including servants; see Domenico Gnoli, “Descriptio Urbis o censimento della popolazione di Roma avanti il sacco borbonico” in Archivio della Società Romana di Storia Patria 17 (1894), pp.375-520 (p.431 [link]).

36. Sauer was a relative of Cochaleus (for whom he tried to negotiate benefices in Rome) and also a correspondent of Pirckheimer. Schulte, op. cit., p.111 [link].

37. Inventarium bonorum quondam Andreae Conerii repertorum in ejus hereditate per D. Blasium Schuryker exequutorem testamenti (Archivio di Stato di Roma, Notari del Tribunale dell’Auditor Camerae, off. 2°, vol. 414, c.148 recto-149 recto). It was discovered by Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani, Storia degli scavi di Roma e notizie intorno le collezioni romane di antichità (Rome 1902), I, p.240 [link]. Transcriptions are provided by Ashby, op. cit. 1904, pp.75-79; Mercati, op. cit. 1952, pp.142-146; Clagett, op. cit., III, pp.530-533.

38. Probably the “Blasius Sweickher ex Nurnberga” who matriculated in law at Vienna on 13 October 1519. See Die Matrikel der Universität Wien, Band 3: 1518-1579, edited by Franz Gall & Willy Szaivert (Graz 1959), p.12; Die Matrikel der Wiener Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät, II. Band: 1442-1557 (Böhlau 2016), p.91 [link]. Ashby, op. cit. 1904, p.75 (“He appears as witness to another document [prepared by the notary Apocellus] as ‘artium et medicinae doctor’”).

39. Alexis Culotta, “Hec domus expectet: The Palazzetto Sander façade and constructing sixteenth-century German identity in Rome” in Opus Incertum 8 (2022), pp.70-79 (p.79 [link]).

40. (Heading) Inventarium bonorum dicti quondam D. Andree repertorum in ca[mera] ipsius in palatio apostolico factum per eundem Blasium exequutorem.

41. A list of the erudite notary’s Greek manuscripts is given by Hobson, op. cit., passim. For details of his career, see Achille François, Elenco di notari che rogarono atti in Roma dal secolo XIV all’anno 1886 (Rome 1886), p.8 (“Notari del Tribunale del A.C., Officio 2: Apocellus Jo. Jacobus 1518-1543” [link]); Claudio De Dominicis, Elenco dei notai romani i cui atti sono conservati nell’Archivio di Stato di Roma (2021), q.v. Apocelli (online, [link]).

42. No contemporary catalogue of Pirckheimer’s library is known (the post-mortem inventory of his possessions excluded books and manuscripts); see Linda Levy Peck, “Uncovering the Arundel Library at the Royal Society: Changing meanings of science and the fate of the Norfolk donation” in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 52 (1998), pp.3-24; David Paisey, “Searching for Pirckheimer’s books in the remains of the Arundel Library at the Royal Society” in Pirckheimer Jahrbuch für Renaissance und Humanismusforschung 22 (2007), pp.159-218.

43. Lanciani, op. cit., I, p.162 [link]; Ashby, op. cit. 1904, passim.

44. Nesselrath, op. cit., pp.160, 164.