Bindings for the Massimi family

The Massimi were one of the oldest aristocratic families in Rome. Domenico Massimi (d. ca 1528), who had amassed a fortune from trade and banking, renovated a palace on the ancient via Papale, where he gathered inscriptions and antique sculpture.1 After its destruction in the Sack of Rome, Pietro (d. 1544), the eldest of his three surviving sons, rebuilt on the same site (1532-1536, design by Baldassare Peruzzi) the so-called Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne; his brother Angelo (1481-1550) built next door (1533-1537, design by Giovanni Mangone) the so-called Palazzo Massimo di Pirro; and his brother Luca (d. 1550) built on the opposite side of the via Papale (design by Antonio da Sangallo). Antiquities from their father’s collection and newly acquired items were installed in the new palazzi, each sumptuously decorated and furnished.

In the late 1460s, Domenico Massimi’s father, Pietro, had invited the German clerics Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz to transfer their press from Subiaco to the family palace in Rome, and on 13 December 1468 the second of their two-volume edition of Cicero’s Epistolae ad familiares, was issued “in domo magnifici uiri Petri de Maximo”. The printers dissolved their partnership in 1473, however Pannartz continued to work in the Massimi palace until 1476. Since no books belonging to either Pietro or Domenico have come to light, it is unknown whether they were consumers of books, or hosted the printing press for solely commercial reasons. Not until the 1530s is there evidence of bibliophilism in the Massimi family, and that collector’s identity remains uncertain.

The three sons of Domenico Massimi established separate households in their respective palaces. Pietro married Faustina Rusticelli, with whom he had five children. The first to reach adulthood was Antonio, and Anthony Hobson supposed Antonio di Pietro Massimi (d. 1561) to be the probable owner of at least five volumes bearing on their covers the Massimi arms, three apparently bound during the 1530s and two during the 1540s.2 Like his father, Antonio was elected to prestigious offices in the municipal administration, becoming a councillor (caporione) of Rione Parione in 1541 and 1545, magistrato di strada in 1546, caporione of Rione Campitelli in 1559, and a magistrato di guerra.3 In 1540-1542, together with Curzio Frangipane, Antonio oversaw the construction of the Campidoglio, and from 1545 until his death, he was one of three deputies of the Fabbrica of St Peter’s, and for some periods the only supervisor of that building project.

Pietro’s brothers Angelo and Luca also held civic offices. Angelo was in addition an abbreviatore delle lettere in the papal chancery, in 1540 guardiano of the Arciconfraternita del Santissimo Salvatore, and at various times in 1543-1548 deputato of the Popolo Romano. He married twice and fathered 12 children. One of Angelo’s sons, Alessandro (d. 1621), had a son named Prospero, born in 1582, and died 3 January 1608.4 This grandson of Angelo Massimi - the only “Prospero” found on the Massimi family tree - may be the individual who wrote “Ex libris Prosper Massimi” on the front endleaf of Lorenzo Valla’s Elegantiarum libri sex (Venice 1536), a volume bound probably in the 1530s with Massimi family arms in gilt on covers, now in the John Rylands University Library (see Census below). Although Luca Massimi was caporione of Rione Parione in 1535, priore dei caporioni in 1539, and conservatore of Rione Parione in 1542, he concentrated his attention on his estates outside Rome, at Pratica di Mare, Prossedi, and Pisterzo. Luca married Virginia Colonna, with whom he had eight children.

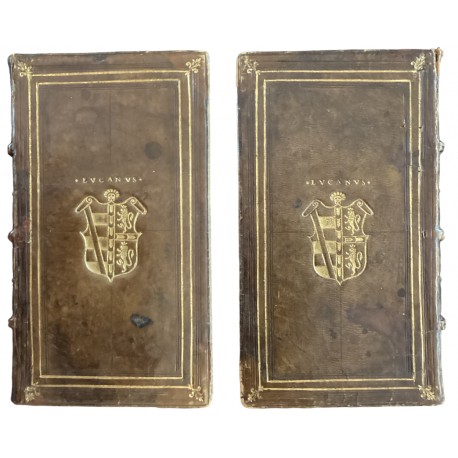

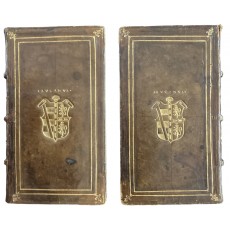

Armorial stamps. Left 1. detail from Lucanus. Right 2. from Sallustius

Altogether, thirteen sixteenth-century bindings adorned with Massimi arms are known; not all can now be traced.5 From the available illustrations, these volumes divide into two groups. The bindings of the first group cover books printed between 1502 and 1544 and are comparatively simple, the covers decorated with frames formed from multiple gilt and blind fillets, or by a blind roll, in the centres a gilt armorial stamp, with the author’s name or title sometimes lettered above in gold. The second group comprises six bindings, on books printed in 1521 and in 1544-1546. A different arms block is utilised, the covers are tooled in gold to a panel design, and decorated with solid tools. Hobson dated these bindings to the 1540s and assigned them to Niccolò Franzese, a binder for the Vatican Library.

1. Valeria Cafà, Palazzo Massimo alle colonne di Baldassarre Peruzzi: Storia di una famiglia romana e del suo palazzo in Rione Parione ([Vicenza] 2007), pp.50-54.

2. Anthony Hobson, “Sanvito’s bindings” in Bartolomeo Sanvito: the life & work of a Renaissance scribe ([Paris] 2009), pp.87-99 & pp.397-398 (p.398). Hobson’s reasoning is obscure: none of these volumes contains any relevant evidence, and Hobson appears to have been swayed by Antonio di Pietro’s involvement in the education of his children.

3. For Antonio di Pietro’s offices in the municipal administration, see Claudio De Dominicis, Membri del Senato della Roma Pontificia: Senatori, Conservatori, Caporioni e loro Priori e Lista d’oro delle famiglie dirigenti (secc. X-XIX) (Rome 2009), p.121 (caporione 1541, Rione Parione), p.123 (caporione 1545, Parione), p.128 (caporione 1559, Campitelli).

4. Alessandro di Angelo held offices in the magistracy in 1576, 1593, 1598, and 1615 (see De Dominicis, op. cit.). He married in 1572 Olimpia de Cuppis (d. 1591), with whom he had eight children. Prospero was the fourth of his six sons.

5. Hobson, op. cit.: Castiglione, Lucretius, Valla, Cicero, Sallustius. The Sallustius is more fully described by Hobson in Craig Kallendorf & Maria Wells, Aldine press books at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center The University of Texas at Austin: a descriptive catalogue (Austin 1998), p.37 (illustration) & p.196. Tammaro de Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), nos. 621-624, 2991. Piccarda Quilici, Legature antiche e di pregio: sec. XIV-XVIII: catalogo (Rome 1995), I, p.147 no. 171 & II, p.48 Fig. 70 (Estienne).

armorial stamp 1

(1) Baldassarre Castiglione, Il libro del cortegiano del conte Baldesar Castiglione (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Heirs of Andrea Torresano, May 1533)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● Bernard Quaritch, London; their Catalogue 166: Examples of the art of book-binding (London 1897), item 361 (“Smooth olive morocco, gilt on the sides with two single parallel fillets, having a leaved flower at each angle. The back has seven alternately thin and thick bands, the thick ones gilt with a horizontal line, the narrow ones with diagonal strokes running downwards from left to right. The edges are simply gilt. - There is, on the sides, an escutcheon in gold with a lettering: Cortegiano. These seem to have been added about 1550. The escutcheon is divided by a pale vair; the first half is fessy of six with a bendlet; the other half is traversed by a fess vair, with a crowned lion rampant above and below.” [link]); Rough list 202: A Catalogue of Spanish & Portuguese and also of Italian Literature (London 1900), item 840 [link]

● David Alexander Robert Lindsay, 28th Earl of Crawford and 11th Earl of Balcarres (1900-1975)

literature

Tammaro de Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 2991 (“Balcarres, The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres. Vitellino marrone; cornici di filetti dorati ed a secco, agli angoli esterni un fiorellino. Nel mezzo l’arme della famiglia Massimo impressa in oro, sormontata dal titolo: Cortegiano. Taglio dorato. Volumi con la medesima arme sono descritti ai nn. 621-623.”)

Anthony Hobson, “Sanvito’s bindings” in Bartolomeo Sanvito: the life & work of a Renaissance scribe ([Paris] 2009), pp.87-99 & pp.397-398 (p.398: “Castiglione: private collection”)

(2) Gaius Valerius Catullus, Catullus. Tibullus. Propertius (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, January 1502)

Image courtesy of Federico Macchi

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● Modena, Biblioteca Estense, ALPHA D 007 025 (opac Pelle rigida, sui piatti impresse cornici dorate con stemma al centro; cucitura su quattro nervi, capitelli cuciti in filo. Tagli dorati. Collocazione precedente Ms. XVIII A H E 39; E V 17)

literature

Giuseppe Fumagalli, L’arte della legatura alla corte degli Estensi (Florence 1913), no. 172 (“Pelle oliva. Inquadratura di riletti dorati e a secco. Nel centro lo stemma dei principi Massimo, cioè, partito: al primo, fasciato d’azzurro e d’argento di sei pezzi alla banda d’oro attraversante sul tutto, al secondo d’argento, alla mezza croce d’azzurro, attraversante sulla partizione, caricata di undici scudetti del campo (nove visibili ma nella lega tura soltanto otto) e accantonata da quattro leoni di rosso (due visibili), armati, linguati e coronati d’oro.”)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 621 (“Legato intorno al 1540 in marr. oliva, dec. dorata come sopra con l’arme della famiglia Massimo”)

(3) Robert Estienne, Dictionariolum puerorum. In hoc nudae tantum, puraeque sunt dictiones, nullo loquendi genere adjecto … [extract from Estienne’s Dictionarium Latinogallicum] (Paris: Robert Estienne, 1544)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, h. I. 28 (opac, [link])

literature

Piccarda Quilici, Legature antiche e di pregio: sec. XIV-XVIII: catalogo (Rome 1995), I, p.147 no. 171 & II, p.48 Fig. 70

(4) Andrea Fulvio, Illustrium imagines (Rome: Giacomo Mazzocchi, 15 November 1517)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● Tammaro de Marinis (1878-1969)

● Gonnelli, Asta 50: Libri autografi e manoscritti, Florence, 6-7 March 2024, lot 395 [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale [RBH 50-395]

● Meda Riquier Rare Books Ltd, London; their Catalogue [for 65th New York International Antiquarian Book Fair, April 3-6, 2025] (London 2025), pp.37-41 [item 9] (€8000; illustrated)

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 622 (“Firenze, raccolta T. De Marinis. Legato come sopra, col medesimo stemma”)

(5) Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, Lucanus (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, July 1515)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● unidentified owner, inscription “Jacobi Becari” on title-page, perhaps Jacopo Bartolomeo Beccari (1682-1766), professor of medicine and chemistry at the University of Bologna

● Luigi Lubrano, Naples; their Bollettino del Bibliofilo: Notizie, illustrazioni di libri a stampa e manoscritti 1 (1919), pp.165-184 (“Legature pregiate del XVI-XVIII secolo”, item 17: Legatura contemporanea in marrocchino scuro con doppia riquadratura filettata in oro ai piatti e quattro fiorellini agli angoli. Al centro stemma in oro interzato: al primo 3 fasce d’oro attraversate da una sbarra, al secondo ed al terzo leone rampante volto a destra, alla parte superiore il tit.: LVCANVS. Ottima conservazione di una legatura preziosa, malgrado l’angolo del dorso sia rotto e leggermente tarlato il piatto posteriore. Taglio dorato.” [link]); Bollettino del Bibliofilo: Notizie, illustrazioni di libri a stampa e manoscritti 2 (1920), pp.329-364 (“Libri rari descritti ed offerti in vendita,” item 5 [link])

● Henri, Comte Chandon de Briailles (1898-1937)

● François, Comte Chandon de Briailles (1892-1953)

● Maurice Rheims & Jacqueline Vidal-Mégret, Bibliothèque de M. le Comte C. de X… Précieuses reliures armoriées ou ornées XVIe et XVIIe siècles; Manuscrits, Paris, 2-3 December 1954, lot 186 (“Aux armes de Massimo … Sur chaque plat, au-dessus des armes, est frappé le titre: Lucanus”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 15,500) [Le Guide du Bibliophile, 6, p.671]

● Pierre Berès, Paris; their Catalogue 57: Livres et manuscrits XIIIe-XVIe siècles (Paris 1957), item 234 (FF 90,000; “Reliure de l’époque maroquin fauve, encadrement de filets dorés et à froid avec fleurons d’angles sur les plats; au centre de chaque plat, armes contemporaines dorées; en noir, au-dessus, le titre; dos à nerfs, tranches dorées … Elle porte les armoiries de la famille Massimo qui peuvent être attribuées a Carlo Massimo … ou à son neveu Lelio”)

● Librairie Paul Jammes, Paris

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 2002) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0190]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection D-M, New York, 18 October 2024, lot 867 [RBH N11499-867]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 623 (“Paris, Libr. Berès (dicembre 1954) … Marr. castano; dec. dorata di filetti, stemma come sopra. Sui piatti il titolo LVCANVS.”)

(6) Titus Lucretius Carus, Lucretius (Venice Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, January 1515)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.148 (opac Sui piatti, impresso in oro stemma della famiglia Massimo … Legatura in pelle su piatti di cartone. - Sui piatti cornici filettate con elementi fitomorfi agli angoli e stemma citato impressi in oro e cornici impresse a secco. - Dorso diviso in compartimenti da tre nervi. - Tagli in oro [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 624 (“Biblioteca Vaticana [De Marinis gift] … Legato come sopra in marocchino giallo”)

Hobson, op. cit., p.398

(7) Lorenzo Valla, Laurentij Vallae Elegantiarum libri sex. Eiusdem de reciprocatione sui, et suus libellus plurimum utilis (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Heirs of Andrea Torresano, 1536)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● Prospero Massimi (1582-1608), inscription “Ex libris Prosper Massimi” on front endpaper (opac)

● Horatio William Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (1813-1894), armorial exlibris with motto, “Fari quae sentiat” (opac)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a selection of valuable books from the library of the late Rt. Hon.ble the Earl of Orford, containing many rare and fine Aldine editions, London, 10-11 June 1895, lot 311 (“contemporary brown Venetian calf, with a coat of arms in centre (rebacked), gilt edges” [link])

● Richard Copley Christie (1830-1901) - bought in sale (18s); armorial exlibris

● Manchester, John Rylands University Library, R213377 (opac Sixteenth-century full calf; multiple blind and gilt fillets to form a border; small gilt flower tools at corners; Massimo [Massimi/Massime] arms stamped in gilt on upper and lower boards; rebacked[?]; spine: four raised gilt-rolled bands; smaller horizontal leather bands with diagonal gilt lines; blind fillets in compartments; all edges gilt and gauffered near boards [link])

literature

Charles W.E. Leigh, Catalogue of the Christie Collection (Manchester 1915), p.441 (“Massimo and H.W. Walpole’s copy” [link])

Hobson, op. cit., p.398 (cites previous shelfmark, 34.h.36)

armorial stamp 2

(8-12) Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. Tullii Ciceronis Epistolae ad Atticum, ad M. Brutum, ad Quintum fratrem (Venice: Paolo Manuzio, November 1544), together with: Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. Tullii Ciceronis orationum pars I. [-III] (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, June 1546), together with: Marcus Tullius Cicero, Rhetoricorum ad C. Herennium libri IIII. Incerto auctore (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, September 1546)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● Bertram Ashburnham, 4th Earl of Ashburnam (1797-1878), pencil inscription at head of front paste-downs “Ashburnham sale July 1 97 / no. 1109” (opac)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the magnificent collection of printed books the property of the Rt. Hon. the Earl of Ashburnham, First portion, London, 25 June-3 July 1897, lot 1109 (“5 vol. contemporary Venetian citron morocco, the sides covered with elegant geometrical scroll tooling in compartments, with titles and arms in centres g. and gauffred edges, a tasteful specimen of Grolieresque binding (repaired)” [link])

● Richard Copley Christie (1830-1901) - bought in sale (£10 10s) (Book Prices Current, [link])

● Richard Copley Christie (1830-1901), armorial exlibris

● Manchester, John Rylands University Library, R213206 (Epistolae), R213155 (Orationes), R213653 (Rhetoricorum) (opac, repeated in each entry: Sixteenth-century Roman full brown goatskin; gilt geometrical and scroll tooling on upper and lower boards, with Massimo [Massimi/Massime] arms by Niccolo Franzese [i.e. Frenchman Nicolas Fery d. 1570]; evidence of ties on upper and lower boards; rebacked spine; five raised bands to spine; gilt stamped Christie armorial saltire to spine; all edges gilt and gauffered)

literature

Leigh, op. cit., p.104 (Rhetoricorum, 1546, as: 4 parts in 1 volume, “Contemporary citron morocco, with geometrical and scroll tooling on the sides. Massimo and Ashburnham copy”), p.108 (Epistolae, 1544, as 1 volume: “Contemporary citron morocco, with geometrical and scroll tooling on the sides. Massimo and Ashburnham copy”), p.110 (Orationes, 1546, as 3 volumes: “Contemporary citron morocco, with geometrical and scroll tooling on the sides. Massimo and Ashburnham copy” [link])

Hobson, op. cit. p.99 (“different stamp of the same arms”; cites previous shelfmarks, 33.c.1-5)

(13) Gaius Sallustius Crispus, C. Crispi Sallustii De coniuratione Catilinae. Eiusdem De bello Iugurthino (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, January 1521)

provenance

● unidentified member of the Massimi family, armorial supralibros

● bookseller’s notation dated: 5 Dec. [18]76, signed: T.A. Jackson

● Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a further portion of the valuable library collected by the late Charles Fairfax Murray, Esq., of London and Florence, London, 17-20 July 1922, lot 934 (“title slightly stained, hole in one leaf (sig. A 8), contemporary Italian, brown morocco, gilt line tooling on sides to a geometrical design forming a border, leafy arabesques solidly gilt, in the centre a coat-of arms, gauffred edges” [link]) [RBH Jul171922-934]

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£9 5s) (Book Auction Records, [link])

● Sir Arthur John Dorman, 1st Bt (1848-1931), exlibris [heir: Sir Bedford Lockwood Dorman, 2nd Bt (1879-1956)]

● Georges Heilbrun, Paris, sold in February 1963 to Uzielli (Kallendorf & Wells)

● Giorgio Uzielli (1915-1984), exlibris

● Austin, TX, University of Texas, Humanities Research Center, Uzielli 164 (opac, [link])

literature

Charles Fairfax Murray, Catalogo dei libri posseduti da Charles Fairfax Murray. Parte prima (London [i.e. Rome] 1899), no. 1990 (“legat. orig. mar. bruno con stemmi sui piatti e dorature” [link])

Charles Fairfax Murray, A list of printed books in the library of Charles Fairfax Murray ([London?] 1907), p.203 (“Sm. 8vo, conty. brown morocco, richly gilt tooled, with arms on sides” [link])

Craig Kallendorf & Maria Wells, Aldine press books at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center The University of Texas at Austin: a descriptive catalogue (Austin 1998), p.37 (illustration) & p.196 no. 186 (“Roman 16th-cent. brown goatskin gilt, with Massimo arms, by Niccolò Franzese” [link])

Hobson, op. cit., p.99