View larger

View larger

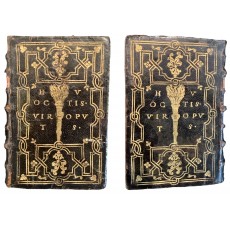

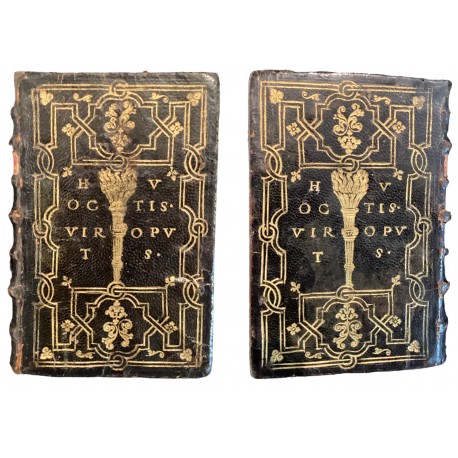

Bindings for an unknown collector using the motto “Hoc virtutis opus”

The motto is derived from Vergil’s Aeneid, Book X, lines 468-469 (roughly, “this is virtue’s task” [link]). It was adopted by two Italian academies,1 however neither devised an impresa which couples the sentiment with an image of a torch, a symbol of widely different meanings, among them the pursuit of knowledge or truth, perseverance, “generosity of spirit and persecuted virtue”.2 Jacopo Gelli claimed that the first individual to use this motto was the celebrated theorist of images, Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti (1522-1597).3

Born in Bologna, Gabriele was educated locally, at the Collegio Ancarano and the university, where he received a classical humanist education, and obtained in 1546 a doctorate in utroque iure. He became professor of civil law at Bologna and in 1552 advocate of the Bolognese senate. Gabriele’s life took a decisive turn in 1556, when he was appointed Auditor of the Sacra Romana Rota. In 1562, he became counsellor to the cardinal legates in the works of the Council of Trent; in 1565, he was created cardinal by Pope Pius IV; and in 1566, he was ordained and elected bishop of Bologna (promoted to archbishop in 1582). By 1543, Gabriele was associated with Prospero Fontana in Bologna’s Accademia degli Affumati, and by 1550, he was acquainted with Achille Bocchi, author of the Symbolicae Quaestiones (1555). At later dates he became friends with Carlo Sigonio and Ulisse Aldrovandi, and consulted both while preparing his Discorso intorno alle immagini sacre e profane (published in 1582).

Gelli’s grounds for associating Gabrielle Paleotti with the Virgilian motto “Hoc virtutis opus” are left unstated.4 In 1953, Anthony Hobson relied on Gelli when tentatively assigning ownership of one of these five bindings (no. 2 in List below) to Gabriele Paleotti.5 By 1965, Hobson’s doubts about Paleotti’s ownership appear to have dissipated: the book was reintroduced as “bound for” Gabriele Paleotti, with the flaming torch described as Gabriele’s personal, symbolic device, and “Hoc virtutis opus” as Gabriele’s motto.6 Paleotti’s residency in Bologna led Hobson to suppose that the binding was Bolognese work. Both of his attributions (to Paleotti and to a Bolognese bindery) were sustained by Tammaro De Marinis.7 While the general features of these bindings remind of earlier works of the local Pflug and Ebeleben bindery,8 the tools employed have yet to be observed on any Bolognese bindings, and the bindings just as likely were made in a provincial shop elsewhere in Italy. The device of a flaming torch has yet to be associated with Gabriele Paleotti.

Details of tools (from upper cover of no. 2 in List below)

Further investigation of Gabriele Paleotti’s library might help to resolve the question of ownership. In 1953, Hobson consulted a catalogue of the Cardinal’s books compiled in 1586, and found no corresponding entries for two of the “Hoc virtutis opus” volumes (nos. 1-2 in List below).9 But this catalogue listed the books in the Cardinal’s clerical library, which in 1595 became the Biblioteca Arcivescovile.10 Other inventories of Gabriele Paleotti’s books are known; for example, one taken by his secretary, Ludovico Nucci, dated 1561;11 and another, possibly made when Paleotti was sent to Rome, in 1590 (he remained there almost continuously until his death in 1597).12

1. Jennifer Montagu, An Index of emblems of the Italian academies (London 1988), p.11.

2. Guelfo Guelfi-Camajani, Vocabolario araldico ad uso degli italiani (Milan 1897), p.264 no. 737 (“Simbolo di generosità d’animo e di virtù perseguitata” [link]).

3. Jacopo Gelli, Divise-motti imprese di famiglie e personaggi italiani (Milan 1916), no. 850 (“Questa è opera di virtù. Il motto è tolto da Virgilio (Aen., X, 469) e fu usato come divisa da’ Paleotti e dai Callison [sic]. Primo a portarla fu Gabriele Paleotti… Con questa divisa il prelato folle attribuire la gloria della propria famiglia non solo alle sue virtù, ma anche a quelle degli antenati, tra i quali re ne furono molli veramente illustri e benemeriti.” [link]). Cf. Julius Dielitz, Die Wahl- und Denksprüche, Feldgeschreie, Losungen, Schlacht- und Völksrufe besonders des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit (Frankfurt am Main 1884), p.134 (citing Collison and Paleotti, only; [link]). “Hoc virtutis opus” does not appear in the index of mottos compiled by Arthur Henkel and Albrecht Schöne, Emblemata: Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart 1976), nor in an index of 1866 mottos found in anthologies of impresa, compiled by Mason Tung, Impresa index: to the collections of Paradin, Giovio, Simeoni, Pittoni, Ruscelli, Contile, Camilli, Capaccio, Bargagli, and Typotius (New York 2006). It appears on a bronze medal (without the torch) cast in 1598 for Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini (1571-1621); see Xavier F. Salomon, “Hoc virtutis opus: Antonio Felice Casoni’s medal of Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini” in The Medal 43 (2003), pp.3-19.

4. In 1670, the Bolognese genealogist Pompeo Dolfi recorded “Hoc virtutis opus” lettered across the blue fess of the Paleotti family’s heraldic shield: D’oro, una fascia azzurra sostenente un monte di sei colli rosso; capo: d’Angiò. P. Dolfi, Cronologia delle famiglie nobili di Bologna con le loro insegne, e nel fine i cimieri (Bologna 1670), p.569 (“Paleotti, col moto [sic] nella fascia Hoc Virtutis opus” [link]). The present writer has identified no surfaces decorated by “Hoc Virtutis opus” and related to the Paleotti; compare, for example, a terracotta wall relief at Savigno, Bologna [link]; and painted fresco decorations in the Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio, Bologna [link].

5. A. Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), no. 65 (“the motto is attributed to Paleotti by Gelli and the attribution seems plausible”).

6. Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 199 (“contemporary Bolognese black morocco gilt, decorated with interlaced fillets, fleurons and rosettes, bound for Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti (1522-97, Archbishop of Bologna) with his device, a flaming torch, and motto Hoc Virtutis Opus in the centre of the side”).

7. T. De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XVI e XVI (Florence 1960), nos. 1402, 1404-1405, placed among the Bolognese bindings (nos. 1, 2, 5 in the List below).

8. In 1953, Hobson dismissed the Pflug and Ebeleben shop as a possible binder, believing that it had ceased about 1551. By 1998, Hobson knew that it remained active throughout the 1560s, binding a copy of the canons and decretals of the Council of Trent (Rome 1564) for Cardinal Paleotti; see A. Hobson & Leonardo Quaquarelli, Legature bolognesi del Rinascimento (Bologna [1998]), p.26.

9. “Catalogus bibliothecae illustrissmi et reverendissimi Domini Gabrielis Paleotti … Anno salutis. MDLXXXVI”; see Inventari dei manoscritti delle biblioteche d’Italia, 79: Bologna: Biblioteca comunale dell’Archiginnasio (Florence 1954), p.16. Gabriele is said to have decanted into this library his family’s books; see Paolo Prodi, Il Cardinale Gabriele Paleotti (Rome 1959-1967), I, pp.52-53; II, p.264-267. Gabriele’s cousin and successor as Archbishop of Bologna, Alfonso Paleotti, absorbed Gabriele’s collection, and made his own catalogue. See Maria Xenia Zevelechi Wells, The Ranuzzi Manuscripts (Austin, TX 1980), no. 24; Madeline McMahon, Primary Source: An Archbishop’s Lost Library Catalog [link].

10. Giorgio Montecchi, “La biblioteca arcivescovile di Bologna: dal card. Paleotti a papa Lambertini” in Produzione e circolazione libraria a Bologna nel Settecento (Bologna 1987), pp.369-382.

11. Bologna, Archivio Isolani, F.30.99.27 (Cartoni Nuovi 54), described by Prodi, op. cit., I, p.109; and by P.O. Kristeller, Iter italicum, Vol. 5 (Alia itinera III and Italy III) (London 1990), p.505 (“Lists of books owned by Card. Paleotti and others. One list was compiled by Lud. Nucci in 1561 and includes Homer in Greek, Boethius, Averroes, Bembo and Castiglione”).

12. Bologna, Archivio Isolani, F.30.99.27 (Cartoni Nuovi 59), described by Kristeller, op. cit, p.506 (“Elenchi di libri e manoscritti del Card. Paleotti spediti a Roma ecc.”).

list of bindings

(1) Giovanni Candido, Commentarii di Giouan Candido giureconsulto de i fatti d’Aquileia (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1544)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa and motto “Hoc Virtvtis Opvs”

● Jacques Techener, Paris; their “Catalogue de livres rares et curieux de littérature, d’histoire, etc., qui se trouvent en vente a la librairie de J. Techener, place du Louvre. No. 1er - Janvier 1847” in Bulletin du bibliophile, huitième serie (1847), p.37 item 20 (FF 36; “mar. noir (Ancienne reliure.) Curieuse reliure, filets à compartiments, dans le genre des reliures de Grolier, et torches allumées, avec cette devise: hoc virtvtis opvs” [link]

● William Henry Corfield (1843-1903), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the collection of books in valuable bindings of the late Professor W.H. Corfield, M.D., 19, Savile, Row, W., comprising early stamped, embroidered, inlays, and other bindings, by binders of various countries and periods, London, 21-23 November 1904, lot 378 (“gilt geometrical design on sides, a flaming torch and the legend ‘Hoc virtutis opus’ in centre; exhibited at the Burlington Fine Arts Club” [link])

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£12)

● possibly Thomas Stainton [notice of forthcoming sales, in The Burlington Magazine 93 (February 1951), p.66: "This library [i.e., books offered in sales in 1920 and 1951] which has escaped the notice of bibliographers, was formed by Thomas Stainton in the last forty years of the nineteenth century. The first books appear to have been purchased about 1864 and the last additions were made at the W.H. Corfield sale in 1904. The collection is remarkable for its fine bindings…”]

● Nathaniel Evelyn William Stainton (1863-1940), Barham Court, Canterbury

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable printed books, illuminated & other manuscripts, and books in fine bindings, London, 26-27 July 1920, lot 519 (“contemporary Italian black morocco tooled and gilt to a geometrical design, in the centre of each cover a flaming torch and the legend ‘Hoc virtutis opus,’ with the bookplate of W.H. Corfield”) [lots 509-552 offered as “The Property of E. Stainton, Esq., Barham Court, Canterbury”]

● Ford - bought in sale (£7-10s) [Book Auction Records, 17, p.547; link]

● Harriet Wilhelmina (née Grimshaw) Stainton (1887-1976)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of a library of printed books, manuscripts and fine bindings; the property of Mrs. Evelyn Stainton, Barham House, Canterbury, London, 26 February 1951, lot 57 & Pl. 14 (“contemporary Italian black morocco gilt, border of interlacing fillets, solid tools at the corners, etc., in the centre the original owner’s device, a flaming torch and motto, hoc virtutis opus, a stylised tool in the compartments of the back … Only one other binding of the unknown collector who used this device and motto is known to us.”) [RBH TREE-57]

● McLeish, London - bought in sale (£62)

● Albert Ehrman (1890-1969), exlibris

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, Broxb. 24.8 (opac, With ALS from Tammaro de Marinis to Albert Ehrman on the binding [link]; Italian binding, mid 16th century, probably bound in Bologna. Black morocco over pasteboard. On both covers, a framework of interlacing gilt double fillets and a variety of floral tools gold-tooled; central flaming torch flanked by ‘hoc virtvtis opvs’ (Virgil, ‘Aeneid’, X 469; motto of Cardinal G. Paleotti of Bologna). Spine in five compartments outlined by blind fillets, with repeating gilt foliate tool. Board edges gilt with an arabesque roll. See de Marinis, ‘La Legatura Artistica’ number 1402 for attribution to Bologna. 160 x 103 x 17 mm [image source])

literature

Burlington Fine Arts Club, Exhibition of bookbindings (London 1891), Case E, no. 54, p. 30 (“Italian binding; black morocco; gold tooling. In the centre, a flaming torch and the legend: Hoc Virtvtis opvs. W. H. Corfield, Esq., M.D.”) & Pl. 34 [link]

New Gallery, Exhibition of Venetian art, The New Gallery Regent St 1894-5 (London [1894]), p.104 no. 768 (“Italian binding; black morocco; gold tooling. In the centre a flaming torch and the legend, Hoc Virtutis Opus. Lent by W. H. Corfield, Esq., MD”) [link]

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 1402 & Pl. 238 (“Marr. scuro; dec. dorata di doppi filetti, nel mezzo una face col motto H | OC | VIR | T | V | TIS | OPV | S. Tolto da Virgilio (Eneide, x 469) il motto fu usato dal cardinale Gabriele Paleotti (1522-1597) che fu arcivescovo di Bologna: J. Gelli, Divise, n. 926”)

(2) Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. Tullii Ciceronis De philosophia volumen secundum (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1552)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa and motto “Hoc Virtvtis Opvs”

● F.J. Welch

● Puttick & Simpson, Catalogue of miscellaneous books including the library of the late F.J. Welch, Esq., London 1-2 November 1909, lot 836

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£3 15s) [Book Prices Current, 24, p.46, “The Library of the late Mr F.J. Welch, of Denmark Hill,” part lot: “Cicero de Philosophia, old black mor. (XVIth century) binding, tooled sides, lettered ‘Hoc Virtutis Opus’, Venetiis 1552”- link]

● Henry “Bogey” Harris (ca 1870-1950)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the valuable collection of early Italian printed books and manuscripts, the property of Henry Harris, Esq., 9 Bedford Square, W.C.1, London, 22-23 June 1936, lot 50 (“contemporary black morocco, sides decorated with a 2-line fillet interlacing to a geometrical design, in the centre of each side a flaming torch and the legend Hoc Virtutis Opus, g. e., back repaired and lower corner rubbed”) [lots 1-150 are “The Property of Henry Harris, Esq.”; RBH 22Jun1936-50]

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£4)

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 199 (“contemporary Bolognese black morocco gilt, decorated with interlaced fillets, fleurons and rosettes, bound for Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti (1522-97, Archbishop of Bologna) with his device, a flaming torch, and motto Hoc Virtutis Opus in the centre of the sides … two other volumes with this device are known”)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£200)

● Giorgio Angiolo Eduardo Uzielli (1915-1984)

● Austin, TX, University of Texas, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Uzielli 273 (opac bound in black morocco; gilt and blind tooled with interlace pattern; center gilt tooled with motto ascribed to Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti: hoc virtutis opus; all edges red under gilt; bookplate of Giorgio Uzielli; bookplate of John Roland Abbey. [link])

literature

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), no. 65 (“Bolognese Binding for Gabriele Paleotti (?), c. 1560”)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 1404 (“Greyfriars, coll. J.R. Abbey”)

Craig Kallendorf & Maria Wells, Aldine press books at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin: A descriptive catalogue (Austin 1998), pp.303-304 no.355a (“gilt design on binding includes torch and motto “hoc virtutis opus,” previously attributed to Cardinal Paleotti (1522-97), Archbishop of Bologna”)

(3) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Rhetoricorum ad C. Herennium libri IIII incerto auctore. Ciceronis De inuentione libri II. De oratore, ad Q. fratrem libri III. Brutus, siue De claris oratoribus, liber I. Orator ad Brutum, Topica ad Trebatium, Oratoriae partitiones, initium libri De optimo genere oratorum (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1550)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa and motto “Hoc Virtvtis Opvs”

● Eugène Piot (1812-1890)

● Charles Pillet & Antoine-Laurent Potier, Livres rares et curieux, manuscrits et imprimés, la plupart ornés de belles reliures françaises et italiennes des XVIe et XVIIe siècles, provenant du cabinet de M. Eug. P…, Paris, 23-30 April 1862, lot 316 (“Reliure italienne du XVIe siècle. Sur les plats, une torche allumée et la devise: Hoc virtutis opus” [link])

● L. Potier, Catalogue de livres choisis en divers genres à vendre à la librairie de L. Potier. Deuxième partie, Belles-lettres (Paris 1863), item 1301 (FF 60; “Mar. n. compart. tr. dor. Belle reliure italienne du XVIe siècle. Sur les plats, une torche allumée et la devise: Hoc virtutis opus.” [link])

● Delbergue-Cormont & Adolphe Labitte, Catalogue des livres rares et précieux, manuscrits et imprimés faisant partie de la librairie de L. Potier, Paris, 29 March-9 April 1870, lot 613 (“mar. n. compart. tr. dor. Belle reliure italienne du seizième siècle. Sur les plats, une torche allumée et la devise: Hoc virtutis opus” [link])

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 48)

● Adolphe Labitte, Catalogue de livres rares et curieux en vente aux prix marques a la Librairie de M. Adolphe Labitte (Paris 1870), item 78 (“Belle reliure italienne du seizième siecle. Sur les plats, une torche allumée et la devise: Hoc virtutis opus” [link])

● Charles Cousin (1822-1894), exlibris, “free endpaper verso inscribed: 2 Oct 81 Cousin.” (opac)

● Maurice Delestre & Adolphe-Jules Durel, Catalogue de livres & manuscrits, la plupart rares et précieux provenant du grenier de Charles Cousin, Paris, 7-11 April 1891, lot 194 (“mar. noir, dorure à la Grolier, tr. dorée. Au centre des plats, un grand flambeau en forme de torche allumée avec cette devise: Hoc Virtutis opus. Belle reliure du XVIme siècle, d’une conservation parfaite” [link])

● Giorgio Angiolo Eduardo Uzielli (1915-1984)

● Austin, TX, University of Texas, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Uzielli 268 (opac bound in black calf skin; gilt and blind tooled with interlace pattern; center gilt tooled with motto ascribed to Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti: Hoc virtutis opus; all edges red under gilt; bookplate of Giorgio Uzielli; bookplate of Charles Cousin; front free endpaper verso inscribed: 2 Oct 81 Cousin. [link])

literature

Kallendorf & Wells, op. cit., pp.292-292 no. 334 & p.45 (“gilt design on binding includes motto ‘hoc virtutis opus,’ once attributed to Cardinal Paleotti (1524-97), Archbishop of Bologna” [onine edition 2008, link])

(4) Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. Tullii Ciceronis Orationum pars III. Corrigente Paulo Manutio (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1550)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa and motto “Hoc Virtvtis Opvs”

● Ludwig Rosenthal, Munich; their Catalogue 111: Seltene und kostbare Bücher (Munich 1906), item 365 (“Veau noir à compartiments dorés, au milieu des plats un flambeau et l’inscription: ‘Hoc virtutis opus’ tr. d. (Genre Grolier)” [link])

● Librairie Théophile Belin, Paris; their Livres à figures sur bois des XVe et XVIe siècles (Paris 1911), item 118 & p.40 (“mar. noir, compart. d’entrelacs, arabesques et fleurs sur les plats, dent. int., tr. dor. … Très curieuse reliure d’Alde. Les plats du vol., portent une torche enflammée avec ces mots en lettres d’or: Hoc virtutis opus” [link])

(5) Paolo Manuzio, In epistolas Ciceronis ad Atticum, Pauli Manutii commentarius (Venice: Paolo Manuzio, 1553)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa and motto “Hoc Virtvtis Opvs”

● Giovanni Sicoré (1775-1834), typographical exlibris lettered “OTIIS IOHANNIS SICORÉ”

● Camillo Meli Lupi, prince of Soragna (1873-1954)

● Carlo Alberto Chiesa, Milan

● Christie Manson & Woods, A fine collection of books printed by Aldus Manutius and his successors at Venice including many in contemporary bindings and with important provenances, London, 3 May 1995, lot 84 (“contemporary Italian gold-tooled black morocco, the sides decorated to an interlace design with gouges and fillets, small tools including acorns, scrolls, rosettes and fleurons, in the centre an impresa of a flaming torch and the motto Hoc virtutis opus, gilt lettering-piece added to spine at a later date, gilt edges, original endpapers, (ties removed)… the device was attributed by Gelli to Gabriele Paleotti (1522-97), Archbishop of Bologna, and A.R.A. Hobson therefore tentatively localised the binding shop in Bologna (French and Italian Collectors and their Bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey, Oxford 1953, no. 65; see also De Marinis II, 1402); however, nothing definite links this small group - a total of four bindings with the device is known - to the Archbishop’s library or even to Bologna, and the question remains open. The design is archaic for the 1550s and the quality of the gold-tooling suggests a provincial shop” [link])

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased at the above sale via Martin Breslauer Inc. [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #0551]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection, D-M, New York, 18 October 2024, lot 937 [link] [RBH N11499-937]

● New York, Morgan Library & Museum, PML 199269 (opac, [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 1405 (“Rocca di Soragna (Parma), raccolta del Principe Bonifacio di Soragna”)