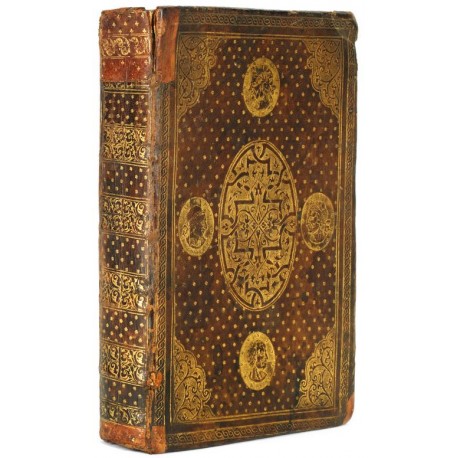

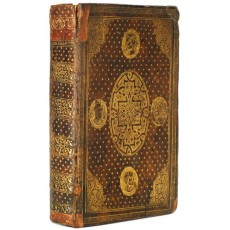

Two English bindings decorated with plaquettes designed by René Boyvin

All four plaquettes appear to be based on engravings by René Boyvin, published at Paris in 1566, as Illvstrivm philosophorvm et poetarvm vetervm effigies XII. Ex antiquis tum marmoreis tum aeneis signis ad viuum expresse & nunc primum in lucem aeditae,2 and soon diffused by other printmakers.3 In the 1566 issue of Boyvin’s suite, the prints are numbered in the matrices: 7 (Xenocrates), 8 (Plato), 10 (Cato), 11 (Cicero). René Boyvin was born at Angers about 1520, and settled in Paris about 1545, joining the workshop of the printmaker Pierre Milan. He was closely involved in Protestant circles, became the portrait engraver for leading reformers, and in 1569 was imprisoned in Paris for his religious beliefs. Boyvin’s print series provided models for craftsmen in several media,4 and also for medallists.5

Engravings by René Boyvin (Paris 1566). Left to right Cato - Cicero - Plato - Xenocrates

Four plaquettes used by the “Morocco Binder” on Jewel, Defence of the Apologie (London 1567). Left to right Cato - Cicero - Plato - Xenocrates

Two plaquettes used by the “Morocco Binder” on Petrarca, Opera (Basel 1554). Cato - Cicero (line drawings from Davenport, Cameo book stamps, nos. XXII, LI)

The “Morocco Binder” was named by Howard Nixon for the reason that about half of the shop’s recorded output employed leather prepared from goatskin, then a material uncommon in English binding workshops.6 Its tools are close copies of those used in a London shop that created bindings for the Royal Court and for Robert Dudley, themselves copied from tools used in the Parisian shop of “Grolier’s Last Binder”. There is speculation that the “Dudley Binder” and the “Morocco Binder” may be the same shop, and also that its proprietor was Thomas Vautrollier (d. 1587), a French Protestant refugee bookbinder and printer, granted letters of denization in England on 9 March 1562, and admitted to the Stationers’ Company on 2 October 1564.7 Among customers of the Morocco Binder were Queen Elizabeth I, two members of the Royal Household, Archbishops Matthew Parker and John Whitgift, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and Sir Rowland Hayward (Lord Mayor of London 1570-1571). The shop bound another copy of Bishop Jewel’s A defence of the Apologie of the Churche of Englande in calfskin for Robert Dudley.8

The spread of the Italian fashion for multiple-medallion ornament on bookbindings, first to Lyon in the mid-1550s, thence to Paris, Geneva, and London, is briefly sketched by Hobson. The Morocco Binder’s two volumes are the earliest of the few English bindings cited. The same centrepiece and pair of cornerpieces are used on both bindings.9 The egg and dart roll border on the Petrarca also appears on the aforementioned copy of Jewel’s Defence of the Apologie bound for the Earl of Leicester; the twisted-rope border on the Jewel has not been noted on other bindings from the Morocco Binder’s shop. The two bindings recall Genevan bindings of the mid 1560s, in the composition of four plaquettes around a large centre ornament, and application of a semis of starry flowers or three-dot tools (compare Hobson, op. cit. 1989, Fig. 110). They strengthen the likelihood that their binder was an émigré, familiar with the plaquette ornament found on French bindings, who was inspired by the plates of Boyvin’s series to obtain new binding tools and to introduce the fashion for multiple plaquette ornament into England.

1. Anthony Hobson, Humanists and bookbinders: the origins and diffusion of the humanistic bookbinding 1459-1559, with a census of historiated plaquette and medallion bindings of the Renaissance (Cambridge 1989), pp.145-146 & p.249 nos. 139 (Cicero) and 140 (Cato) only. The two supplements to the Census published by Hobson in 1994 and 2000 do not add examples of these plaquettes.

2. The opac of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France records a copy (RP-13913) with the title also in French: Les effigies de XII Illustres Philosophes et Poetes anciens, Tirées des Marbres et Medalles antiques au plus pres du naturel. Nouvellement taillées et mises en lumiere, with imprint: Paris, Philippe [Gaultier] de Rouillé, 1566 [link; digitised for Gallica, link]. The matrice for Cicero was used in the Rouillé edition of M. Tullij Ciceronis Opera omnia quae exstant, a Dionysio Lambino (Paris 1566) [link]. A.P.F. Robert-Dumesnil, Le peintre-graveur français (Paris 1850), VIII, pp.54-57 nos. 91-102 (“Nous ne craignons pas d’avancer que tous ces portraits sont de pure fantaisie” [link]). Jacques Levron, René Boyvin, graveur angevin du XVIe siècle: avec le catalogue de son oeuvre et la reproduction de 114 estampes (Paris 1941), pp.68-69 nos. 58-69.

3. A copy with different Latin title (only) and imprint “Lutetiae Parisiorum 1566” is digitised (Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute, ID: 1387-634; [link]). André Linzeler, Inventaire du fonds français. Graveurs du seizième siècle (Paris 1932-1938), I, pp.183-187, recording also engraved and woodcut copies (direction of some portraits is reversed) [link]. Boyvin’s prints were copied (twelve plates) also in Italy: Girolamo Olgiati, Illustrium philosophorum et sapientium effigies ab eorum numismatibus extractae (Venice: Girolamo Olgiati, editions ca 1567/1568-1583). Compare, Cato: original (Boyvin’s monogram, numbered upper left 10; edition Paris: P. de Roville, 1566 [link; link]; edition Paris: s.n., 1566 [link]), engraved copy in same direction (no monogram, unnumbered; no publication line [link]), copy in opposite direction (no monogram, unnumbered; [Venice: Girolamo Olgiati, ca 1567-1583] [link; link]). Cicero: original (Boyvin’s monogram, numbered upper left 11; edition Paris: P. de Roville, 1566 [link; link]; edition Paris: s.n., 1566 [link]), engraved copy in same direction (no monogram, unnumbered; no publication line [link]), copy in opposite direction (no monogram; [Venice: Girolamo Olgiati, ca 1567-1583] [unnumbered, link; numbered 11 link]). Plato: original (Boyvin’s monogram, numbered upper left 8; edition Paris: P. de Roville, 1566 [link; link]; edition Paris: s.n., 1566 [link]), engraved copy in same direction (no monogram, unnumbered; no publication line [link]), copy in opposite direction (no monogram, numbered 8; [Venice: Girolamo Olgiati, ca 1567-1583] [link; link]). Xenocrates: original (Boyvin’s monogram, numbered upper left 7; edition Paris: P. de Roville, 1566 [link; link]; edition Paris: s.n., 1566 [link]), engraved copy in same direction (no monogram, unnumbered; no publication line [link]), copy in opposite direction (no monogram, unnumbered; [Venice: Girolamo Olgiati, ca 1567-1583] [link; link]).

4. An oval medallion in glazed terracotta portraying the bust of a man after the antique was discovered recently among “Les fouilles du Grand Louvre - Cour Napoléon et Carrousel” (Musée national de la Renaissance - Château d’Écouen; 1983-1986, EP 996) and given an attribution to Bernard Palissy: “Palissy s’inspire ici de la suite de portraits d’auteurs Antiques gravée par René Boyvin dans les Illustrium Philosophorum et poetarum veterum effigies (Paris, 1566).” Bruno Dufay, Yves Kisch, Pierre-Jean Trombetta, Dominique Poulain, Yves Roumégoux, “L’atelier parisien de Bernard Palissy” in Revue de l’Art, no. 78 (1987), pp.33-60 (Fig. 63) [link].

5. Boyvin’s engraved portrait of Clement Marot (dated 1576) was copied closely by an anonymous medallist (London, British Museum, M.8722/M.2152; Mark Jones, A catalogue of French medals in the British Museum, I: 1402-1610 (London 1982), p.264 nos. 270-271).

6. Howard M. Nixon, “English Bookbindings XXII: A binding by the Morocco Binder, c. 1563” in The Book Collector 6 (1957), p.278; H.M. Nixon, “English bookbinding” in Transactions: fourth International Congress of Bibliophiles, London, 27 September-2 October 1965 (London 1967), pp.81-94 (“… trained in one of the best Paris ateliers of the day; and was therefore almost certainly a Frenchman”); H.M. Nixon, “Elizabethan gold-tooled bindings” in Essays in honour of Victor Scholderer (Mainz 1970), pp.219-270 (pp.237-243, listing 24 bindings); H.M. Nixon, Sixteenth-century gold-tooled bookbindings in the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York 1971), pp.184, 186; H.M. Nixon, “Some Huguenot bookbinders” in Proceeding of the Huguenot Society of London 23 (1981), pp.319-329; Mirjam Foot, in Lambeth Palace Library: Treasures from the collection of the Archbishops of Canterbury (London 2010), p.106 (“As the Dudley binder probably worked until c. 1562 and the Morocco binder started around 1563-64, it is likely that these two groups were the work of one atelier. Possibly the Dudley binder left or sold tools to the Morocco binder, the latter being his successor.”)

7. Hobson, op. cit. 1989, p.145.

8. Washington, DC, Folger Shakespeare Library, STC 14600 Copy 3; Nixon, “Elizabethan gold-tooled bindings,” op. cit., p.238 no. 17; Fine and historic bookbindings from the Folger Shakespeare Library (Washington, DC 1992), no. 3:4.

9. They appear also on Plutarchus, Le vite de gli huomini illustri greci et romani (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1564), in the British Library, Henry Davis Gift. For that binding, see H.M. Nixon, “Elizabethan gold-tooled bindings” op. cit., p.237 no. 10 (“decorated with three tools and a pair of corner blocks which can be identified with certainty on other members of the group”); Mirjam M. Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: A collection of bookbindings, Volume 2, A catalogue of North-European bindings (London 1983), no. 46.

bindings

(1) John Jewel, A defence of the Apologie of the Churche of Englande, conteininge an answeare to a certaine booke lately set foorthe by M. Hardinge, and entituled, A confutation of &c. By Iohn Iewel Bishop of Sarisburie (London: Henry Wykes, 27 October 1567)

provenance

● unidentified owner, occasional contemporary marginalia

● unidentified owner, inscription “J. Walrond”, perhaps John Walronde, rector of Combe Raleigh (Diocese Exeter) in 1555-1558 [Clergy of the Church of England database (cced), link]

● unidentified owner, inscription “Robert Cossins book bought of Mr. John Waldronde”, with a 4-line note mentioning “a booke of matters” and “the epistoll of philemon” also included in the transaction, perhaps Robert Cosines (d. 1596), vicar of Frampton (Diocese Bristol) [cced, link; alternatively, Robert Cosyn, rector of Crick (Diocese Peterborough) in 1560; Robert Cossins (1787-1815), Kepwick, North Yorkshire]

● George Moberly (1803-1885), inscription, and “Balliol College, Oxford, 1832”, posthumous label on front pastedown [matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford, 1822; BA 1825, MA 1828; Fellow of Balliol, 1826-1834; afterwards headmaster of Winchester (1835-1866), and Bishop of Salisbury (1869)]

● James Patrick Ronaldson Lyell (1871-1948)

● Hodgson & Co., A catalogue of the remaining portion of the library of James P.R. Lyell, J.P. (dec’d.), sold by order of the executors, London, 20-21 July 1950, lot 270

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£7 10s)

● William George Arthur Ormsby-Gore, 4th Baron Harlech (1885-1964)

● Jasset David Cody Ormsby-Gore, 7th Baron Harlech (b. 1986)

● Bonhams, The Contents of Glyn Cywarch - The Property of Lord Harlech, London, 29 March 2017, lot 321 [link] [RBH 24150-321]

● T. Kimball Brooker, acquired in the above sale [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #2343]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part V, London, 10 December 2024, lot 1129 (£69,850) [link] [RBH L24405-1129]

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1989, p.146 (cited, but not seen; “present ownership unknown”)

(2) Petrarca, Opera quae extant omnia (Basel: Heinrich Petri, [1554])

provenance

● English royal collection (Fletcher)

● London, British Library, C24c14

literature

Henry Wheatley, Remarkable bindings in the British Museum selected for their beauty or historic interest (London 1889), Pl. 38 [link]

William Fletcher, Foreign bookbindings in the British Museum: illustrations of sixty-three examples selected on account of their beauty or historical interest (London 1896), Pl. 27 (“French binding of the middle of the 16th century … From the Old Royal Collection”) [link]

Cyril Davenport, Cameo book-stamps (London 1911), nos. 23 (Cato) and 51 (Cicero)

E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author's collection (London 1928), p.73 (as a French binding)

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), III, p.76 (reproduces Davenport’s drawings)

Nixon, “Elizabethan gold-tooled bindings” op. cit, p.237 no. 2, p.239 (“heavily restored and with the gold repainted”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1989, pp.145-146 & p.249 nos. 139 (Cicero) & 140 (Cato)

British Library, Database of bookbindings [link]