View larger

View larger

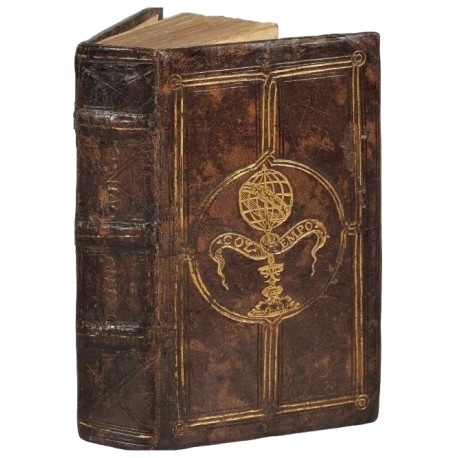

Bindings for an owner with the motto “Col Tempo”

The two bindings known to Goldschmidt were on vernacular works published in Venice in 1531 and 1533, and Goldschmidt presumed they were bound near those dates, somewhere in “Northern Italy”. By 1953, the two bindings had migrated into the collections of Albert Ehrman and J.R. Abbey respectively. Anthony Hobson, describing the Abbey volume in that year, refined Goldschmidt’s suggestion, locating the bindings to a shop in Venice, or in one of the Venetian provinces.3 In 1985, Hobson relocated the bindings to Rome, to a shop patronised by another, unidentified Roman collector, whose impresa was a dog pursuing a bird, and he listed a third “Col Tempo” binding, also in brown goatskin with spine title, which he had discovered in an English private collection.4 The same three bindings were afterwards studied by T. Kimball Brooker, who placed their owner in the context of other Roman collectors of the 1520s and 1530s who were commissioning bindings with longitudinal spine titles.5

A fourth binding, likewise in brown goatskin with a spine title (covers only, the text inside is missing), was identified in the National Library of Malta, and published by Joseph Schirò in 1999.6 A fifth binding, also in brown goatskin, identically decorated, with a spine title, and covering a vernacular work printed at Toscolano in 1527, appeared on the market in 2015. It strengthens Hobson’s supposition, that the owner of the “Col Tempo” bindings was frequenting a shop whose speciality was Venetian editions of vernacular works.

The armillary sphere, its stand, and the lettered banner are impressed from a single stamp. Its designer has depicted on the broad ecliptic band five signs of the zodiac, without concern for their usual order: we read (from left to right) the two fish of Pisces – the lion of Leo – the Virgin of Virgo – the scorpion of Scorpio – the centaur of Sagittarius. This choice of signs could be arbitrary; if deliberate, it may be a clue to the identity of the owner, or else to the model on which the designer based his stamp.7

The motto “Col tempo” is associated in variant forms with the D’Este family and the Copisano family of Chieri (“Con il tempo”), neither of which offers a possible owner for these bindings.8 If the owner was in fact Venetian, only travelling through, or temporarily resident in Rome, then his use of “Col Tempo” was topical. In the early years of the 16th century the passage of time was a popular theme in the lyric verse of several poets, notably Panfilo Sassi, Filenio Gallo, Marcello Filosseno and Niccolò Liburnio. In one work of Sassi (first published 1511), 20 of its 38 triplets commence with the expression “Col tempo”; the phrase is repeated 13 times in a single sonnet by Gallo.9 Combined with the device of a siren, “Col tempo” had appeared as an emblem in Vittore Carpaccio’s “Miracolo della reliquia della Croce al ponte di Rialto”, painted in 1494, and, famously, on the cartellino in Giorgione’s portrait “La Vecchia” of about 1506. The device of an armillary sphere is most uncommon. It was used by the Starrabba, a noble family originally from Burgundy in France, settled in Sicily in the 14th century, displayed alone on the shield (D’azzurro alla sfera armillare d’oro); the motto “Col Tempo,” however, is nowhere associated with the Starrabba family.10

1. E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author’s collection (London 1928), no. 157 & Pl. 57.

2. Mostra storica della legatura artistica in Palazzo Pitti (Florence 1922), no. 487, lent by Don Diego Cristiano Antonio Francesco Pignatelli (1855-1938).

3. Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), p.135 & Fig. 64. Graham Pollard sustained the “Venice or northern Italy” domicile of the binder, and declared that these two bindings with titles tooled directly on to the spine leather are the earliest known examples of the practice; see “Changes in the style of bookbinding, 1550-1830” in The Library, fifth series, 11 (1956), pp.71-94 (p.83).

4. Anthony Hobson, “Some sixteenth-century buyers of books in Rome and elsewhere” in Humanistica Lovaniensia 34A (1985), pp.65-75 (pp.68-69) [link]. Hobson locates three bindings with an oval impresa of a dog chasing a bird and motto “Non curo l’ fin purch’ alt’ impresa segua”.

5. T. Kimball Brooker, Upright works: the emergence of the vertical library in the sixteenth century, Thesis (Ph.D.), University of Chicago, 1996, p.827: “Exhibit 10: Roman bindings with impresa (mid-1530s): ‘Col Tempo’ on an astrolabe on both covers”.

6. Valetta, National Library of Malta, Cab-9. Joseph Schirò, in Fine bookbindings from the National Library of Malta (Malta 1999), p.34 (illustrated).

7. Compare the woodcut title-compartment by the Monogrammist LA (Lucantonio degli Uberti) for Girolamo Tagliente's Libro d’abaco printed at Venice ca 1520, where Ptolemy and Pythagorus are depicted beside an armillary sphere [link] .

8. Jacopo Gelli, Divise-motti imprese di famiglie e personaggi italiani (Milan 1916), nos. 461 (Con il Tempo), 504 (Cum tempore). A copy of the 1478 Jenson Plutarchus with painted border decoration incorporating unspecified “arms in lower margin and motto ‘Col Tempo’ on a scroll” was offered by Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable printed books, illuminated & other manuscripts, London, 25-26 July 1923, lot 353 [link] (the volume has not been traced). The motto (in German, as “Mit Zeit”), with an artichoke, was the emblem of Francesco Sforza (1401-1466).

9. Peter Lüdemann, “‘Col tempo impara scientia e virtude’. Spunti per una rilettura iconologica della ‘Vecchia’ di Giorgione” in Studi tizianeschi 9 (2016), pp.11-35 (pp.28-29, 32).

10. Antonio Mango di Casalgerardo, Nobiliario di Sicilia (Palermo 1915), II, p.189; Vittorio Spreti, Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana (Milan 1932), VI, p.471 [link].

list of bindings

(1) Gaius Iulius Caesar, Commentarii di Caio Giulio Cesare, tradotti di latino in volgar lingua (Venice: Francesco Bindoni & Maffeo Pasini, October 1531)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa of an astrolabe lettered “Col Tempo” (back lettered: Comentari. D. C.)

● Collegio dei Gesuiti in San Vigilio, Siena, inscription “Biblioth. Coll. Sem. S. Vigilii Soc. Jesu”

● Alfred Piat (1826-1896)

● Paul Chevalier with Édouard Bartaumieux & Charles Porquet with Ém. Paul et Fils et Guillemin, Catalogue de la bibliothèque de feu m. Alfred Piat, Troisième partie, Paris, 28 March-3 May 1898, lot 5799 (“Reliure du XVIe siècle portant au centre des plats, dans un encadrement d’entrelacs une sphère, autour du pied de laquelle s’enroule une banderole avec ces mots: col tempo”[link])

● J. & J. Leighton, London; their Catalogue of early-printed, and other interesting books and manuscripts. Second part: C (London [1905?], item 891 (£4 4s; “original Venetian binding of calf, with gilt and blind line borders on sides enclosing circle with device of globe on pedestal with motto ‘Col Tempo’, gilt edges” [link])

● E.P. Goldschmidt, London (taken into stock 1 October 1923 from E.P.G.’s private collection; E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., Stock Books 1921-1981, #1311, in Grolier Club Library [link]; sold to Ehrman 23 March 1950, £20)

● Albert Ehrman (1890-1969)

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, Broxb. 24.9 (opac “Italian binding, early 16th century, probably bound in Venice. Brown morocco over pasteboard. On both covers, interlacing double fillets in gilt and blind forming a frame, within which a central compartment containing an astrolabe with motto ‘Col tempo’. Spine in four compartments, with transverse gilt lettered title. Gilt textblock edges.” [image, source])

literature

E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author’s collection (London 1928), no. 157 (“I have not been able to discover so far for whom these bindings with the astrolabe and the ‘Col Tempo’ device have been made. I know of only one other specimen of this binding, in a private collection.”) & Pl. 57

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei Secoli XV e XVI. Notizie ed elenchi (Florence 1960), no. 2175 (as Venetian)

Anthony Hobson, “Some sixteenth-century buyers of books in Rome and elsewhere” in Humanistica Lovaniensia: Roma humanistica: Studia in honorem Revi adm. Dni Dni Iosaei Ruysschaert 34A (1985), pp.65-75, no. 1 (as Roman)

Mirjam Foot, The Henry Davis Gift A Collection of bookbindings, Volume 3: A Catalogue of South-European bindings (London 2010), p.361 (as Roman)

(2) Herodotus, Delle guerre de’ greci et de’ persi, tradotto di greco in lingua italiana (Venice: Melchiorre Sessa, 1533)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa of an astrolabe lettered “Col Tempo” (back lettered: Herod Oto)

● Don Diego Cristiano Antonio Francesco Pignatelli (1855-1938)

● Nicolas Rauch, Catalogue 1: Catalogue de très beaux livres (Mies 1948), item 53 (CHF 3500; “[citing Goldschmidt] … Ces rarissimes reliures doivent être situées entre 1530 et 1535, parmi les toutes premières faites spécialement pour un bibliophile, dont le nom est resté inconnu”)

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the celebrated library, the property of Major J.R. Abbey, Part III, London, 19-21 June 1967, lot 1894 (“contemporary North Italian brown goatskin”)

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£170)

● Henry Davis (1897-1977)

● London, British Library, Henry Davis Gift 758

literature

Mostra storica della legatura artistica in Palazzo Pitti (Florence 1922), no. 487 (“S.E. il Principe Diego Pignatelli d’Angiò, Roma”)

Goldschmidt, op. cit., p.244

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), p.135 & Fig. 64

Hobson, op. cit., 1985, no. 3 (pp.68-69: “the endleaves of the ‘Col Tempo’ Herodotus have a watermark of the type of Briquet 6088, found in Rome in 1535”)

Foot, op. cit., no. 300

British Library, Database of Bookbindings [link]

(3) Lettere volgari (?) (empty binding, 170 x 100 mm)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa of an astrolabe lettered “Col Tempo” (back lettered: Lettere V.)

● Valetta, National Library of Malta, Cab-9

literature

Fine bookbindings from the National Library of Malta and the Magistral Palace Library and Archives, Sovereign Military Order of Malta, Rome (Malta 1999), p.34 (illustrated)

(4) Lodovico Martelli, Le rime volgari di Lodouico di Lorenzo Martelli (Rome: Antonio Blado, 1533), bound with Jacopo Sannazzaro, Le rime di m. Giacobo Sannazaro nobile napolitano (Venice: Melchiorre Sessa, 1532), bound with Jacopo Sannazzaro, Arcadia di messer Giacomo Sanazaro napolitano (Venice: Melchiorre Sessa, 1532)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa of an astrolabe lettered “Col Tempo” (back lettered: Rime d. Lo[dovico] M[artelli] Rime S. [Arcadia?])

● unidentified owner, inscription “Chi nella gratia sua brama di stare | e no vi essendo | Per non morire ei non vol[er] piu tornare” on front pastedown

● Hon. George Matthew Fortescue (1791-1877) (?)

● Fortescue, family library (Boconnoc and Dropmore)

● John Desmond Grenville Fortescue (1919-2017), Boconnoc, Cornwall

● Bonhams, Fine books and manuscripts, London, 21 March 2018, lot 117 (“3-line verse in an early Italian hand on front paste-down, contemporary brown panelled morocco gilt, the sides with double gilt ruled outer border and a central circular compartment, formed by the intersection of gilt and blind-stamped fillets, containing an astrolabe with representations of Zodiacal signs, supported by a sculptured pedestal, with a banner bearing the motto “Col tempo”, spine lettered in gilt “Rime D.Lo.M./Rime S. [-]rca.” (scuffed affecting one or two letters, some loss to extremities), g.e., traces of ties” [link]) [RBH 24633-117]

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased in the above sale [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #2436]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part VII, London, 11 July 2025, lot 1762 (£4445) [link]

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1985, no. 2

(5) Xenophon, Della vita di Cyro re de Persi tradotto in lingua toscana (Toscolano: Alessandro Paganini, 9 August 1527), bound with Quintus Curtius Rufus, Quinto Curtio da P. Candido di latino in volgare tradotto (Venice: Vittore Ravani & Compagni, August 1531)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, impresa of an astrolabe lettered “Col Tempo” (back lettered: Xeno Quinto)

● unidentified owner, inscription < Romub…? > dated 1593 on lower endleaf

● unidentified owner, coat of arms with paschal lamb drawn in ink on upper endleaf

● Arthur Lauria, Paris

● Maurice Burrus (1882-1959), his acquisition label dated 1936

● Christie’s Paris, Maurice Burrus (1882-1959): la bibliothèque d’un homme de goût. Première partie, Paris, 15 December 2015, lot 229 (realised €10,625 [link]) [RBH 4035-229]

● T. Kimball Brooker, purchased in the above sale [Bibliotheca Brookeriana #2052]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part VII, London, 11 July 2025, lot 1865 (£5080) [link]

● New York, The Morgan Library & Museum