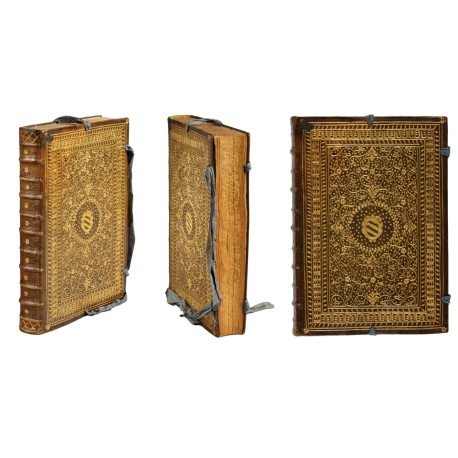

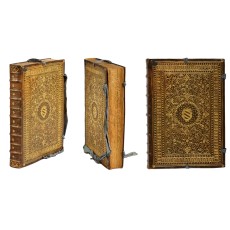

Bindings made for members of the Ferreri family of Savona and Sciacca, Sicily

The origin of a group of eight, elaborately gold-tooled brown goatskin bindings has long perplexed bookbinding historians. Four of the group bear the arms of the Ferreri family within a cartouche in the centres of the covers; another has the initials B.F. (Bernardo Ferreri) at the top of its upper cover. The remaining three bindings have a centre ornament composed of four fleurons surrounded by stars, and no external sign of Ferreri ownership.

Arms of the Ferreri family, D’oro a tre bande d’azzurro, drawn by Giovanni De Marchis, ca 1750

(Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma, Ms 215, p.263) [link]

The eight volumes preserve the Ferreri family’s copies of numerous agreements made with each other and with the Ventimiglia family, marquises of Geraci, from about 1557 until 1571. Long-standing financial instability had impelled the Ventimiglia to mortgage and eventually surrender their Sicilian feudal estates and even entire baronies to the brothers Bernardo (d. 1575), Nicolò (d. 1568) and Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), Ligurian noblemen and entrepreneurs, involved in the wholesale grain trade, tax collecting, and moneylending, from a base at Sciacca in western Sicily. Each brother managed a different part of the business, with Paolo devoting himself with ever greater success to banking and shipowning. In a long series of transactions, he and his elder brother Nicolò had acquired loans secured by Ventimiglia properties, and by 1572 Giovanni III Ventimiglia was forced to sell his feudal estates of Pollina and San Mauro to Paolo, and a year later, to accept the return of those fiefs in exchange for the baronies of Pettineo and Migaido.1

The eldest of the three brothers, Bernardo, returned to Savona about 1547, where he built a palace in the Via Quarda Superiore (afterwards Grassi Lamba Doria),2 leaving Nicolò and Paolo in Sicily to manage the business. Bernardo came back to Sicily in 1567 during a credit crisis, however he was unable to save Nicolò, who was bankrupted, and executed under torture in 1568 by order of the Viceroy, Francesco Ferdinando d’Ávalos, Marquis de Pescara. Paolo continued to prosper and in 1571 he commenced building a palace in Palermo.3 Upon Paolo’s death (28 December 1575), his estates and the barony of Pettineo passed to the elder of his two daughters, Geromima, who (by papal dispensation) married in 1580 her cousin (Bernardo’s son, Marcantonio), securing thereby the family wealth. The Sicilian nobility often repaid loans with marriage contracts, and so, in 1599, Paolo’s other daughter, Violante, married Simone Ventimiglia.

The bindings on these eight volumes fall into three groups, with no links between them. Bindings in the largest group (see List below, nos. 2, 4, 5, 6) have two tools in common: a palmette leaf (used to fill a border); and a fleuron (used to compose a centre ornament on 2, 5, 6; placed at corners of the border on 2, 5, 6; placed elsewhere amongst swirling stems on 2, 4, 5). Only no. 4 of this group displays the Ferreri arms (D’oro a tre bande d’azzurro). The bindings in the second group (nos. 1, 3, 7) have in common a centre block containing painted arms of the Ferreri family (1, 3); a border filled with leafy branches (3, 7); a fleuron (repeated at inner corners of the frame on 3, 7); a triple-dot tool in the background (1, 3, 7). No image is available for the binding in the third group (no. 8), which De Marinis described as “Marr. castano; sui piatti, in alto, le iniziali B.F. Bindelle di seta verde; taglio inciso”.

Judging by available descriptions, no document in these eight volumes postdates the death of Bernardo Ferreri (1575). One binding (8) probably was commissioned by Bernardo, as it bears his initials on the cover. Another (2), containing contracts for purchases Bernardo made of grain and land from Paolo in 1571-1572, also copies of Paolo’s testament (3 December 1571) and his own (28 August 1572), may also have belonged to Bernardo. The remaining six volumes house mostly documents relating either to Nicolò and Paulo’s transactions, or to Paolo’s transactions alone, with Giovanni III Ventimiglia and his widowed mother, Maria Antonia (1539-1585), who held the right (ius luendi) of repurchase of the mortgaged estates. A post-mortem inventory of Paolo’s chattels, conducted by the Palermitan notary Giacomo Vacante, 21 March 1576, is said to list 59 volumes of documents relating to his and Nicolò’s business activities, each composed of about 200 folios, of which some were “libri” and the rest “giornale” (presumably day-ledgers).4 It may be that these eight volumes were once part of the same business archive.

When they began to leak onto the market in the mid-1950s, Anthony Hobson considered these bindings to be products of a Sicilian workshop (1956), despite the lack of comparable examples. Frederick Adams soon opined that the tools were Venetian (1958), and De Marinis, in his entry for volume (4) (1966), embroidered that argument. Howard Nixon was undecided (1971), wondering whether one group might be Venetian and the other perhaps Sicilian, decorated with tools transported there from Venice. Mirjam Foot favoured Venice (1978, 2010). Hobson’s final comment (1989) was that all the bindings must be Venetian, or all Sicilian.

Although some volumes contain numerous blank leaves (44 in no. 1, 22 in no. 2, about 30 in 3, 149 in no. 4, etc.), the conjecture that these might have been “blank books”, obtained in Venice, or elsewhere, with the documents copied in later, is untenable. Small losses caused by the binder’s knife (in no. 1), the folding and docketing of the quires (in no. 2), together with other evidence, prove that the documents were already written when bound in the volume. Since is difficult to imagine that the documents were transcribed anywhere but in Palermo - indeed, several in no. 6 are attested “facta Collatione cum originale” by the Palermitan notary, Giovanni Domenico Licciardi - it follows that they were either bound locally, or transported from Sicily to the Italian peninsula for binding. The Ferreri were shipowners, however their routes were directed towards Spain and towards Genoa and Lyon, not Venice.

The cataloguers of these volumes have given little information about the watermarks in the paper. From the evidence reported so far, the paper appears to have been manufactured in Liguria. The endleaves of (1) are reported to be a paper with watermark of “a crescent with lunar penumbra surmounted by a trefoil cross, accompanied by the letters AI, very similar to Briquet no. 5249,” a paper of “indisputably Genoese origin”.5 The watermark in the endpapers of (6) is a circle, charged with three birds, surmounted by a cross and accompanied by the letters “A I”, not recorded by Briquet, but probably from the same maker as Briquet 5249.6 Several documents in (4) and in (6) are written on a paper with a large glove or gantelet mark with cinquefoil and initials “M J”, another Genoese paper.7 Similar marks with (and without) the letter “A” also occur in volume (4).

Watermarks observed in no. 4

1. Orazio Cancila, I Ventimiglia di Geraci (1258-1619) (Palermo 2016).

2. Guido Malandra, Bernardo Ferrero e il suo palazzo (Savona 1990).

3. Camillo Filangeri, “Il palazzo di Paolo Ferreri a Palermo” in Atti della Accademia di Scienze Lettere e Arti di Palermo, Parte seconda: Lettere, fifth series, 15 (1994-1995), pp.121-170.

4. Filangeri, op. cit., pp.135, 149, with a partial transcription (by Natale Finocchio) of the document (Archivio di Stato di Palermo, Fondo Notarile, I Stanza, Notaio Giacomo Vacante, 6976).

5. Adams, op. cit., p.37. Briquet observed no. 5249 in a document in Genoa, Archivio di Stato, dated 1589); see Briquet online [link, image] Another drawing of this mark, dated “1589 à 93”, is Pl. 28 no. 222 in Briquet’s “Papier et Filigranes des Archives de Gênes, 1154 à 1700” in Briquet’s Opuscula (Hilversum 1955), p.195.

6. Cf. Briquet, Les Filigranes, no. 3251, a Genoese paper of 1570, with a single bird within a circle; see Briquet online [link].

7. Briquet, op. cit., 1955, Pl. 42 no. 343 (1564).

list of bindings

(1) Notarial documents, 1567-1569

provenance

● Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), or another member of his family

● “acquired from a London dealer in the summer of 1956” (Eighth Report)

● New York, Morgan Library & Museum, MA. 1757 (opac Contemporary Sicilian binding of brown morocco, gilt with the armorial stamp of the Ferreri family impressed and painted in the center on both covers [link])

literature

Pierpont Morgan Library, Eighth Annual Report to the Fellows (New York 1958), pp.36-38 (illustrated)

Howard Nixon, Sixteenth century gold-tooled bookbindings in the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York 1971), no. 48 [considers this and no. 3 below as possibly Sicilian: “we may well be dealing with tools acquired from Venice tool-cutters for use in Sicily”]

(2) Notarial documents, 1571-1572

provenance

● Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), or another member of his family

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of printed books, illuminated manuscripts, autograph letters and historical documents, London, 25-27 June 1956, lot 630 (illustrated; “olive morocco richly gilt, triple borders, central compartment decorated with various floral tools and also small tools of a lion and an eagle, four ties intact of yellow silk, edges gilt and gauffered … The manuscript contains copies of various notarial documents relating to the Ferreri, and dated Palermo, 1571-72. There is no reason to doubt that the binding is of the same place and date. We believe that this is the first elaborately decorated Sicilian binding of the 16th century to be reproduced (though another, decorated with a view of Messina and covering a manuscript Sallust, was exhibited at the Pitti Palace in 1922, no. 223 of the catalogue) and its mixture of Venetian and Spanish ornaments is particularly interesting.”) [lots 611-639 offered as “Other Properties”]

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£115) [RBH SEAL-630]

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby’s, Catalogue of the celebrated library of the late Major J.R. Abbey. The eleventh and final portion, London, 19 June 1989, lot 3039 (“This is one of at least five extant volumes of documents concerning the families of Ferreri and Ventimiglia, of Palermo, Sicily, which seem to have remained undisturbed until their dispersal in 1956-1958”; in 1956, to Maggs, for Major Abbey)

● “Brown” - bought in sale (£15,400) [RBH Julius-3039]

(3) Notarial documents, 1567-1569

provenance

● Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), or another member of his family

● Sotheby & Co., Printed books, illuminated manuscripts, fine bindings, autograph letters and historical documents, London, 22-23 October 1956, lot 167 (“From the same bindery as a companion volume, sold in these rooms June 27, 1956, lot 630, with reproduction in the catalogue. A third volume in the series has also been reported.”) [lots 158-216 offered as “Other Properties”]

● “Rivers” - bought in sale (£115) [RBH Tungsten-167]

● Charles van der Elst (1904-1982)

● Ader Picard Tajan & Claude Guérin with Dominique Courvoisier, Précieux livres anciens, Monte Carlo, 13 May 1985, lot 87 (upper cover illustrated)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 120,000)

literature

Nixon, op. cit., p.188 (“The Morgan manuscript and the example sold in October 1956 … are not only identical in size and date; they share a number of tools in common including the use of the triple-dot tool on the background; and they have smaller spines with raised bands and no half-bands”)

(4) Notarial documents, 1557-1571

provenance

● Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), or another member of his family

● Martin Breslauer, London; their Catalogue 90: Manuscripts and printed books from the eighth to the present century (London 1958), item 36 & Pl. 19 (£350; “In an outstanding Venetian binding of c. 1560, olive morocco profusely gilt; in centre of both covers the Gerace arms in a circular field dotted with stars and surrounded by a wreath, in the central panel leafy arabesques interspersed with stars, etc., broad outer border formed by various leaf-shaped tools, back with 12 bands, 5 being raised higher than the others, a floral tool in centre of each compartment, gilt and blind-tooled lines; beautifully gilt and gauffred edges; with the 6 original ties. (300 by 210 mm.).”); Catalogue 92: Manuscripts and printed books from the thirteenth to the present century on many subjects. Including further sections of the library of the late Wilfred Merton, F.S.A. (London 1960), item 103 and Pl. 27 (£350; “Our binding belongs to a group of four executed in very similar if not identical style for the same family; one of them, recently acquired by the Morgan Library, has been discussed by Mrs. [sic!] F.B. Adams, in conjunction with the three others … He postulates a Sicilian origin for at least his and one other of the bindings (both of which are smaller and appear to be less skilfully tooled) and describes our theory [i.e. “no double of Venetian origin”] concerning our volume as ‘not impossible’“)

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982)

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York; their Catalogue 104/II: Fine books in fine bindings from the fourteenth to the present century (New York 1981), item 172 ($16,000)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1991) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #4014; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Magnificent Books and Bindings, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 35 - catalogue online, link]

literature

Exposition de reliures de la Renaissance: collection Jean Furstenberg: 30 September 1961 (Paris 1961), no. 51

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 71

Tammaro De Marinis, Die italienischen Renaissance-Einbände der Bibliothek Fürstenberg (Hamburg 1966), pp.174-175

(5) Notarial documents, [dates unknown]

provenance

● Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), or another member of his family

● Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, 74 B 413 RE

literature

Franz Anselm Schmitt, Kostbare Einbände, seltene Drucke: aus der Schatzkammer der Badischen Landesbibliothek: Neuerwerbungen 1955 bis 1974 (Karlsruhe 1974), pp.42-43 (“Ferrero-Gerace Familie. Kalligraphische Papierhandschrift, 238 Bl., etwa 1560. Kopialbuch mit Abschriften von Dokumenten, die sich auf den sizilianischen Grundbesitz der Familie Ferrero und Gerace, Grafen von Ventimiglia, beziehen”)

(6) Notarial documents, 1572-1573

provenance

● Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), or another member of his family

● Il Polifilo, Milan

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, autograph letters and historical documents, London, 13-14 March 1961, lot 441 (illustrated; the cataloguer refers to nos. 2 and 4 above, also to 1 and 3, stating latter two “have no tool in common with the first group, but the similarities are so close that all are probably from the same workshop”; “It has been suggested that these bindings are not Palermo work but were purchased in Venice as blank books. The present volume however does not seem to have been bound as a blank book, as the watermark of the endpapers is different from the watermark of the text pages. The former is a shield, charged with three birds, surmounted by a cross and accompanied by the letters A.L., not recorded by Briquet but probably from the same source as Briquet 5249, a mark found in the Morgan Library volume.”)

● Henry Davis (1897-1977)

● British Library, Henry Davis Gift 870

literature

Mirjam Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: A Collection of bookbindings, 1: Studies in the history of bookbinding (London 1978), p.318 (“we shall have to reject Mr Nixon’s suggestion that [it] could have been made in Sicily”)

M. Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: A Collection of bookbindings, 3: A Catalogue of South-European bindings (London 2010), no. 345 (“a binding probably made in Venice, c. 1573”)

British Library, Database of bookbindings [link]

(7) Notarial documents, 1559-1573

provenance

● Paolo Ferreri (d. 1575), or another member of his family

● Pierre Berès, Paris

● Pierre Bergé et associés & Jean-Baptiste de Proyart, Pierre Berès, 80 ans de passion: 6eme vente, fonds de la librairie Pierre Berès, des incunables à nos jours, 4eme partie, Paris, 17-18 December 2007, lot 384

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (€24,500)

● Librairie Amélie Sourget; their “Firsts Italia” [Prima Mostra Mercato Virtuale del Libro Antico e Raro, 18-22 March 2021] (€49,000)

(8) Notarial documents, [dates unknown]

provenance

● Bernardo Ferreri (d. 1575), supralibros, initials B.F. on upper cover

● Andrea Bocca (De Marinis)

● possibly Martin Breslauer, London [a pencil note by Henry Davis in his volume, now British Library (no. 6 above), reports “Febr[uary] 1964. A further binding offered by Breslauer with the Ferreri Arms and initials B.F. Documents on vellum dated 1567-1569”)

● unlocated

literature

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 2498 (“Torino, conte Andrea Bocca”)