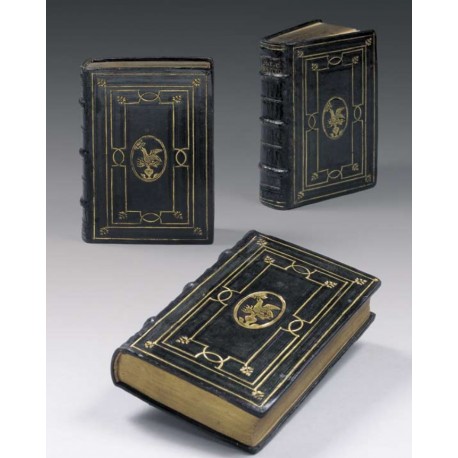

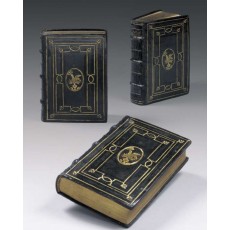

Bindings with a Phoenix device & the Genoese “Grimaldi Binder”

In 1975, Anthony Hobson drew attention to a group of ten or eleven bindings of the 1560s, each having on its covers an oval gilt stamp of a phoenix, not in relief (like a plaquette binding), but impressed by an engraved tool. They imitate the bindings decorated with a plaquette of Apollo and Pegasus (although there is no accompanying motto), which Hobson had linked to the Genoese patrician Giovanni Battista Grimaldi (ca 1524-1612). Their antiquated design – multiple gilt and blind straight borders with acute angle or semi-circular interlace – and a pair of leaf tools reminded Hobson of the Roman binder Niccolò Franzese’s work of the early 1540s, which he took as sure signs of a provincial binder. From various evidence, including watermarks in the endpapers characteristic of Lombardy and Genoa, he located the bindings to Genoa, and designated the shop “The Grimaldi Binder”.

Binding stamps (from left to right)

1. The Genoese “Grimaldi Binder” (no. 11) [link]

2. The Bolognese “Binder of Ulrich Fugger's Bible” (Appendix, no. a)

3. Anonymous Ferrarese (?) binder (Appendix, no. b)

4. Anonymous Venetian binder (Appendix, no. c)

Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari’s devices (from left to right)

1. 1543 Dolce, Thyeste [link]

2. 1546 Osiander [link]

3. 1542 Orlando furioso [link]

The stamp of a phoenix featured on these bindings resembles the devices employed by the printer, Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari, whose shop in Venice was located “all’insegna della Fenice”.1 Hobson could find however no evidence of a branch of the Giolito firm in Genoa, so he discarded the twin hypotheses that these were either Giolito’s personal copies, or “publisher’s bindings”, bindings a publisher might place on books displayed in a shop (see Appendix below). Hobson surmised that the stamp was the impresa of the Milanese Accademia dei Fenici, known to have several Genoese members, and guessed that the books belonged to Giovanni Battista Oliva Grimaldi, Duca di Terranova (d. 1582). Hobson thought that Battista Grimaldi could have been inspired, or even guided, by his namesake, the owner of the “Apollo and Pegasus” bindings, when in 1560 he began to furnish the studiolo of his newly-built Palazzo della Meridiana.2 In 1999, Hobson withdrew his suggestion that the phoenix device might indicate a member of the Academici dei Fenici, while sustaining the Genoese origin of the bindings. He revived the possibility that they were made by or for a presumed Giolito branch in the city, and cited three more bindings having the same phoenix stamp on their covers (nos. 1, 2, 15 in List below). Hobson’s list is recapitulated below, augmented by two bindings (nos. 3-4).3

Eight-volume set of the 1550-1552 Aldine Cicero, broken by Bernard Breslauer in 1950

Eight phoenix device bindings cover volumes of the 1550-1552 Aldine Cicero, four cover books printed at Basel between 1541-1555, and the remaining three are on Venetian imprints of 1548-1555, including one printed by Gabriele Giolito himself, his Orlando furioso of 1555. The Cicero is first recorded in the 1921 sale catalogue of Lord Vernon’s library at Sudbury Hill, where described as bearing “the family arms of Giolito of Ferrara”, the eight volumes offered in a single lot, and bought by Maggs (£25 15s). By 1930, the set was in Munich, illustrated in Catalogue 93 of Jacques Rosenthal, having lost that attribution;4 it was immediately purchased by the Florentine marchand-amateur Tammaro De Marinis. In 1949, the Cicero returned to London, presented in Catalogue 67 of the booksellers Martin Breslauer, with folding frontispiece illustration, as “Bound for Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari” (priced £780).5 When re-offered in Catalogue 71 in 1950, and again unsold, Bernard Breslauer broke the set into five parts, selling that same year De philosophia (2 volumes, 1552) to J.R. Abbey and Epistolae ad Atticum (1552) to Albert Ehrman. By 1952, Breslauer had sold Orationum pars I [-III] (3 volumes, 1550) to the bookseller Nicolas Rauch in Geneva, and Epistolae familiares (1552) to Pierre Berès in Paris. The circumstances of his sale of Rhetoricorum ad C. Herennium libri IIII, and its present whereabouts, are unknown.

When he came to describe Ehrman’s volume of the Cicero, in 1956, Howard Nixon concluded “it seems safe to assume that the binding is in some way related to Giolito … If this is so, it would seem likely that the book was from Giolito’s private library…”.6 De Marinis, who in 1960 had proposed Vittoria Colonna as owner of the phoenix device bindings,7 recanted in 1966, recognising the device on the Epistolae familiares as “das Emblem der Druckerei des Gabriel Giolito”, without venturing that it belonged to Gabriele Giolito himself.8 Anthony Hobson, describing Abbey’s volume of the set, in the June 1965 sale catalogue of his library, considered them Roman bindings, and “likely that they belonged to Gabriel Giolito, the Venetian printer”.9 As we have seen, by 1975 Hobson had changed his mind, and by 1999, once again. In his last (published) reference to the phoenix device bindings, Hobson re-positions them beside three bindings he assumes were made by or for the managers of the Giolito branches in Bologna10 and Ferrara,11 and for the main bookshop in Venice (see Appendix, below).12 Each of those bindings displays a different version of a phoenix device; none is identical with the device appearing on the Genoese phoenix device bindings. In his earlier work, Hobson accepted at face value Giolito’s deposition in 1565 before a tribunal of the Inquisition, when he named the cities where his firm had outlets, and did not mention Genoa.13 In 1999, Hobson took that statement with a grain of salt,14 suggesting that the phoenix device bindings might after all relate to the firm’s activities in Genoa. Ongoing research into commercial networks in the Renaissance may eventually resolve the matter.15

In addition to the volumes featuring the phoenix device, Hobson identified six bindings decorated by tools belonging to the same kit. Their covers are tooled to a panel design in blind and gold, the latter interlaced, with gilt leaf tools set in the angles, like the phoenix device bindings; three have a vertical spine title (the titles are lettered horizontally on the phoenix device bindings). The panelling and tools remind strongly of Roman bindings, and indeed De Marinis had mistaken them as such. One is the Grimaldorum Codex, a cartulary containing copies of documents relating to the Ansaldo Branch of the Grimaldi House, bound about 1561 in black goatskin, tooled in gold and blind with interlacing panels and leaf tools.16 Another manuscript, the Carmelite friar Constanzo Fusco’s “In acta apostolorum vigiliae,” bound in green goatskin, is lettered on its covers with the names of the dedicatee, marchese Giuseppe Malaspina di Fosdinovo (1533-1565), and of the author.17 The remaining four bindings are on printed books: a volume containing three, separately printed works of Pico della Mirandola, bound up in brown morocco, with an oval stamp of Phaeton falling from his chariot and the motto “Nosce te ipsum” of an unidentified owner in centres;18 and three works printed at Rome in 1562 by Paolo Manuzio,19 each with the name of the owner, Annibale Minali (d. 1617), Commendatore di San Giovanni di Prè in Genoa, lettered on the covers.20

1. The Giolito press employed about 30 different devices featuring a phoenix, most depicting the mythical bird turned toward the sun, rising from either a winged globe or amphora emanating flames, with one or more mottos (Vivo morte refecta mea, De la mia morte eterna vita i vivo, Semper eadem), and invariably the initials IGF (Giovanni Giolito De Ferrari, in use 1539) or GGF (Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari, in use 1540-1578).

2. Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: an enquiry into the formation and dispersal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), pp.97-100.

3. Anthony Hobson, Renaissance book collecting (Cambridge 1999), p.127.

4. Jacques Rosenthal, Katalog 93: Frühe Holzschnittbücher, Druckwerke des XVI. Jahrhunderts, spanische Bücher vor 1650, schöne Einbände (Munich 1930), item 604 (price RM 1800). The firm’s archive copy, deposited in the Stadtarchiv München (Nachlass Rosenthal), and now digitised, is annotated “Nach Hobson (Sotheby) ein Giolito-Einband vgl. Karte vom 12.7.32” and records the date of sale to De Marinis [link].

5. Martin Breslauer, Catalogue 67: One hundred fine books on many subjects (London 1949), item 28: “…That these volumes did indeed come from his library is shown by the fact that his device does not occur on a book emanating from his own press (in which case one might assume that the bindings were ‘publishers’ bindings’), but on a beautiful and accurate edition of Cicero produced by Giolito’s rival Aldus.”.

6. Howard Nixon, Broxbourne Library: styles and designs of bookbindings, from the 12th to the 20th century (London 1956), no. 32.

7. Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), nos. 910-913 (as Roman bindings).

8. Tammaro De Marinis, Die italienischen Renaissance-Einbände der Bibliothek Fürstenberg (Hamburg 1966), pp.162-163.

9. Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection: the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 198.

10. Modena, Biblioteca Estense, α 2. 9: Petrarca, Il Petrarcha con l’espositione d’Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1545) [see List below, no. a]. Bound with a cupid on the upper cover, and a version of the Giolito device on lower cover. Giuseppe Fumagalli, L’arte della legatura alla corte degli Estensi, a Ferrara e a Modena, dal sec. XV al XIX. Col catalogo delle legature pregevoli della Biblioteca Estense di Modena (Florence 1913), no. 255 and Pl. IX; Bibliothèque nationale de France, Trésors des bibliothèques d’Italie, IVe-XVIe siècles (Paris 1950), no. 366; Tammaro De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1327 & Pl. 228 (as a Bolognese binding); Anthony Hobson & Leonardo Quaquarelli, Legature bolognesi del Rinascimento (Bologna 1998), p.28 no. 10; Hobson, op. cit. 1999, p.127 (as a Bolognese binding, by the “Binder of Ulrich Fugger’s Bible”).

11. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Library, Kane MS. 44. Suetonius, “De vita Caesarum” (manuscript written in 1433 in Milan by the scribe Milanus Burrus) [see List below, no. b]. Bound in dark brown goatskin, a version of Giolito’s phoenix device (wings elevated, initials GGF) on covers.

12. Cambridge, Harvard College, Houghton Library, *IC5 Ar434 516o 1556c. Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1556) [see List below, no. c].

13. Giolito declared branches in Padua, Ferrara, Bologna, and Naples; see Salvatore Bongi, Annali di Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari da Trino di Monferrato (Rome 1890), I, pp.ciii-cvi: “Constitutum Domini Gabrielis Joliti Mercatoris Librorum” (15 May 1565, transcribed from the document in Venice, Archivio di Stato, Processi, Busta 20) [link]. Pasquale Pironti, Un processo dell’inquisizione a Napoli (Gabriele Giolito e Giovan Battista Cappello) (Naples 1982), esp. p.50.

14. Hobson, op. cit. 1999, p.127: “he [Giolito] may have been economical with the truth.”

15. Angela Nuovo & Chris Coppens, Giolito e la stampa nell’Italia del XVI secolo (Geneva 2005), pp.151-169, and for these bindings p.464; Angela Nuovo, The Italian book trade in the Renaissance (Leiden & Boston 2013), pp.173-181.

16. Genoa, Biblioteca Civico Berio, m.r.Cf.Arm.21. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 6, pp.187-188 no. 143 & Pl. 24. Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 833bis (as Roman).

17. Rome, Biblioteca Angelica, Ms. 1442. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 5. De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 666 (as Roman). Margherita Cavalli & Fiammetta Terlizzi, Legature di pregio in Angelica, Secoli XV-XVIII (Rome 1991), pp.18-19 no. 8 (“Legatura romana della metà del secolo XVI in marocchino verde…”, illustrated).

18. London, British Library, G.11761. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 1 & Pl. 23. De Marinis, op. cit., no. 833 & Pl. 138 (as Roman). Anthony Hobson has suggested that this volume and another (Marsilio Ficino, Platonica theologica de immortalitate animorum, Florence: Antonio Miscomini, 1482; Ravenna, Biblioteca Classense, Inc 24), according to De Marinis (op. cit., no. 3001) similarly decorated, belonged to Battista Grimaldi; see his “A Genoese book collector” in Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 2012, pp.208-212 (p.208).

19. A copy of Cardinal Reginald Pole’s De Concilio (now untraced); De virginitate opuscula Sanctorum doctorum, Ambrosii, Hieronymi et Augustini and Sancti Ioannis Chrysostomi De virginitate liber a Iulio Pogiano conuersus, both offered by Chariot & De Bure frères, Catalogue des livres de M. *** consistant principalement en livres anciens éditions des Alde, Paris, 5-10 December 1827, lots 32 and 50 (reputedly the stock of the bookseller Jean-Pierre Giegler of Milan, mixed with books from T.-B. Emeric-David’s library), later in the Vernon and Holford collections (Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, The Holford Library, Part II. Catalogue of extremely choice and valuable books principally from Continental presses, and in superb morocco bindings, forming part of the collections removed from Dorchester House, Park Lane, the property of Lt.-Col. Sir George Holford, London, 5-9 December 1927, lots 24 and 186), bought by the booksellers Bernard Quaritch, by whom sold in 1951 to Henry Davis, now British Library, Henry Davis Gift 846-847. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 7 and p. 222 no. 8. Mirjam Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: A Collection of bookbindings, volume 3: A Catalogue of South-European bindings (London 2010), nos. 328-329.

20. See the notice of his father by M.C. Giannini, “Minali, Donato Matteo” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 74 (2010).

genoese bindings with a phoenix stamp on covers

(1) Appianus, De bellis punicis liber de bellis syriacis liber de bellis parthicis liber de bellis mithridaticis liber de bellis civilibus libri V de bellis Gallicis liber ([Basel: Hieronymus Froben & Nikolaus Episcopius], 1554)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● Genoa, Biblioteca Universitaria, 2.G.VI.38

literature

Mostra di legature dei secoli XV-XIX, Genova, Palazzo dell’Accademia, 9 gennaio-3 febbraio 1976 (Genoa [1975]), no. 64 (“Pelle marrone; sui piatti, impressi in oro e a secco, riquadrature filettate, cornice a linee rette e curve del tipo ‘Grolier’, agli angoli piccoli ferri aldini pieni, placchetta centrale con la figura della fenice; dorso decorato in oro e a secco, recante il nome dell’autore, con nove nervi di differente spessore disposti alternativamente, mutilo nella parte inferiore; taglio dorato e inciso a motivi puntiformi e cordami.” [link])

Anthony Hobson, Renaissance book collecting (Cambridge 1999), p.127

(2) Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso, con la giunta di cinque canti d’un nuouo libro del medesimo (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari et fratelli, 1555)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● William Horatio Crawford (1815-1888)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, The Lakelands Library. Catalogue of the rare & valuable books, manuscripts & engravings, of the late W.H. Crawford, Esq. Lakelands, Co. Cork, London, 12-23 March 1891, lot 164 (“fine copy in old Venetian brown morocco, covered in gold tooling in the Grolier style, gilt édges, with device of Gabriel Giolito as centre ornament in gold on sides” [link])

● Ellis - bought in sale (£7 15s)

● Oxford, Taylor Institution, ARCH.8o.IT.1555(1)

literature

Fine bindings 1500-1700 from Oxford libraries: catalogue of an exhibition (Oxford 1968), no. 18

Hobson, op. cit. 1999, p.127

(3-4) Ambrogio Calepino, Dictionarium. In quo restituendo atque exornando cum multa praesititimus (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1552)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● Finarte, Libri, autografi e stampe, Rome, 20 June 2019, lot 27 (“in ciascun volume piccole riparazioni marginali su 4-5 carte, piccolo foro di tarlo all’angolo inferiore esterno dal fascicolo 2m del vol. I, bella legatura coeva in pelle impressa a secco e in oro con cornice di filetti intersecati, piccoli motivi angolari fitomorfi e medaglione centrale con fenice, dorso a 4 nervi intervallati da piccoli cordoni, tagli dorati, abrasioni, piccola mancanza alla cuffia superiore del vol. I.”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (realised €17,500)

● Meda Riquier Rare Books, London; their Catalogue ([London] 2020), pp.34-37

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 2020) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0814]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library. The Aldine collection A-C. Publications of the Aldine and Giunta Presses and related books, New York, 12 October 2024, lot 234 [link]

● New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, 199047-48 (opac [link])

literature

Unrecorded

(5-7) Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. Tullii Ciceronis Orationum pars I [-III]. Corrigente Paulo Manutio (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1550)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● unidentified owner, initials “P.J.C.” (“P.J.O”?) [see nos. 11-12 below]

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of printed books and a few manuscripts comprising the property of A.R. Goldie, Esq. … also a further selection from the library of the Right Hon. Lord Vernon, Sudbury Hall, Derby, London, 19-21 October 1921, lot 304 (“together 8 vol. 16th century Italian binding of dark blue morocco, bands, a gilt and blind lines round sides, a centre panel of blind and gilt lines, the latter interlaced at sides, the whole enclosing the family arms of Giolito of Ferrara (some joints a little weak), g.e.”)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£25 15s; in set of 8 volumes); their Catalogue 489: Book bindings : Historical & decorative (London 1927), item 247 (set of eight volumes, £42 10s) [link]

● Jacques Rosenthal, Munich, collation note “HD” (Helmut Domizlaff, then an employee of the firm); their Katalog 93: Frühe Holzschnittbücher, Druckwerke des XVI. Jahrhunderts, spanische Bücher vor 1650, schöne Einbände (Munich 1930), item 604 (illustrated; price RM 1800; in set of 8 volumes; “in ovalem Mittelfeld ein Vogel auf einer Vase, nach der Sonne pickend”) [link]

● Libreria antiquaria T. De Marinis & C., Florence (in set of eight volumes) [acquired from Rosenthal in September-October 1930, see Rosenthal shop copy of Katalog 93, now Stadtarchiv München [link] “604. T. de Marinis, Florenz 19.9.1930 | 6.X.1930”; ms. note: “Nach Hobson (Sotheby) ein Giolito-Einband vgl. Karte vom 12.7.32”]

● Martin Breslauer, London; their Catalogue 67: One hundred fine books on many subjects (London 1949), item 28 (£780; in set of 8 volumes); Catalogue 71: A selection of fine books & manuscripts (London 1950) item 22 (£780; in set of 8 volumes) [Breslauer subsequently broke up the set into five parts: (1) Epistolae ad Atticum 1551; (2) De Philosophia 1552, in two volumes; (3) Epistolae familiares 1552; (4) Orationes 1550, in three volumes; (5) Rhetoricorum libri IV (and three other works) 1550]

● Nicolas Rauch, Geneva; their Catalogue 4: Très beaux livres; almanachs (Geneva 1952), item 120 (CHF 3200; “Très belle reliure vénitienne de l’époque, faite pour Gabriel Giolito…”)

● Gianfranco Alessandrini (1926-2001)

● Pierre Berès, Paris

● Pierre Bergé & Jean-Baptiste de Proyart, Vente Alde Manuce (1450-1515), une collection, Geneva, 19 November 2004, lot 126 (illustrated; chf 61,184)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased at the above sale) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0519]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library. The Aldine collection A-C. Publications of the Aldine and Giunta Presses and related books, New York, 12 October 2024, lot 349 [link]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: an enquiry into the formation and dispersal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), p.97 no. 4 (part set)

(8) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Rhetoricorum ad C. Herennium libri IIII incerto auctore. Ciceronis De inuentione libri II. De oratore, ad Q. fratrem libri III. Brutus, siue De claris oratoribus, liber I. Orator ad Brutum, Topica ad Trebatium, Oratoriae partitiones, initium libri De optimo genere oratorum. Corrigente Paulo Manutio [four parts in 1 volume] (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1550)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of printed books and a few manuscripts comprising the property of A.R. Goldie, Esq. … also a further selection from the library of the Right Hon. Lord Vernon, Sudbury Hall, Derby, London, 19-21 October 1921, lot 304 (in set of 8 volumes)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£25 15s; in set of 8 volumes); their Catalogue 489: Book bindings : Historical & decorative (London 1927), item 247 (set of eight volumes, £42 10s) [link]

● Jacques Rosenthal, Munich; their Katalog 93: Frühe Holzschnittbücher, Druckwerke des XVI. Jahrhunderts, spanische Bücher vor 1650, schöne Einbände (Munich 1930), item 604 (illustrated; price RM 1800; in set of 8 volumes) [link]

● Libreria antiquaria T. De Marinis & C., Florence (in set of eight volumes) [see above]

● Martin Breslauer, London; their Catalogue 67: One hundred fine books on many subjects (London 1949), item 28 (£780; in set of 8 volumes); Catalogue 71: A selection of fine books & manuscripts (London 1950) item 22 (£780; in set of 8 volumes) [Breslauer subsequently broke up the set into five parts: (1) Epistolae ad Atticum 1551; (2) De Philosophia 1552, in two volumes; (3) Epistolae familiares 1552; (4) Orationes 1550, in three volumes; (5) Rhetoricorum libri IV (and three other works) 1550]

● present location unknown

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 4 (part set)

(9) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Epistolae ad Atticum, ad M. Brutum, ad Quintum fratrem, multorum locorum correctione illustratae (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, October 1551)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of printed books and a few manuscripts comprising the property of A.R. Goldie, Esq. … also a further selection from the library of the Right Hon. Lord Vernon, Sudbury Hall, Derby, London, 19-21 October 1921, lot 304 (in set of 8 volumes)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£25 15s; in set of 8 volumes); their Catalogue 489: Book bindings : Historical & decorative (London 1927), item 247 (set of eight volumes, £42 10s) [link]

● Jacques Rosenthal, Munich; their Katalog 93: Frühe Holzschnittbücher, Druckwerke des XVI. Jahrhunderts, spanische Bücher vor 1650, schöne Einbände (Munich 1930), item 604 (illustrated; price RM 1800; in set of 8 volumes) [link]

● Libreria antiquaria T. De Marinis & C., Florence (in set of eight volumes) [see above]

● Martin Breslauer, London; their Catalogue 67: One hundred fine books on many subjects (London 1949), item 28 (£780; in set of 8 volumes); Catalogue 71: A selection of fine books & manuscripts (London 1950) item 22 (£780; in set of 8 volumes) [Breslauer subsequently broke up the set into five parts: (1) Epistolae ad Atticum 1551; (2) De Philosophia 1552, in two volumes; (3) Epistolae familiares 1552; (4) Orationes 1550, in three volumes; (5) Rhetoricorum libri IV (and three other works) 1550]

● Albert Ehrman (1890-1969), “acquired in 1950 from Martin Breslauer” (Nixon)

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, Broxb. 10.21 [image, link; image, link]

literature

Howard Nixon, Broxbourne Library: styles and designs of bookbindings, from the 12th to the 20th century (London 1956), no. 32

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 912bis

Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 4 (part set)

(10) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Epistolae familiares. Pauli Manutij Scholia (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1552)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of printed books and a few manuscripts comprising the property of A.R. Goldie, Esq. … also a further selection from the library of the Right Hon. Lord Vernon, Sudbury Hall, Derby, London, 19-21 October 1921, lot 304 (in set of 8 volumes)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£25 15s; in set of 8 volumes); their Catalogue 489: Book bindings : Historical & decorative (London 1927), item 247 (set of eight volumes, £42 10s) [link]

● Jacques Rosenthal, Munich; their Katalog 93: Frühe Holzschnittbücher, Druckwerke des XVI. Jahrhunderts, spanische Bücher vor 1650, schöne Einbände (Munich 1930), item 604 (illustrated; price RM 1800; in set of 8 volumes) [link]

● Libreria antiquaria T. De Marinis & C., Florence [see above]

● Martin Breslauer, London; their Catalogue 67: One hundred fine books on many subjects (London 1949), item 28 (£780; in set of 8 volumes); Catalogue 71: A selection of fine books & manuscripts (London 1950) item 22 (£780; in set of 8 volumes) [Breslauer subsequently broke up the set into five parts: (1) Epistolae ad Atticum 1551; (2) De Philosophia 1552, in two volumes; (3) Epistolae familiares 1552; (4) Orationes 1550, in three volumes; (5) Rhetoricorum libri IV (and three other works) 1550]

● Pierre Berès, Paris; their Catalogue 51: Livres italiens des quinzième et seizième siècles, xylographies (Paris 1952), item 58 (FF 90,000; “Remarquable reliure Vénitienne originale portant, doré au centre de chaque plat, l’emblème du phénix de l’imprimeur vénitien Gabriel Giolito di Ferrari … De la bibliothèque de Lord Vernon”)

● Nicolas Rauch, Auction 7: Précieux incunables, éditions Aldines, livres rares du XVIe au XIXe s., livres modernes illustrés par des peintres de la bibliothèque de M. B*** et d’autres provenances, Geneva, 29-30 March 1954, lot 79 & Pl. 7 (“… faite pour Gabriel Giolito”)

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982), exlibris

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1980) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0541]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library. The Aldine collection A-C. Publications of the Aldine and Giunta Presses and related books, New York, 12 October 2024, lot 352 [link]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Exposition de reliures de la Renaissance: collection Jean Furstenberg, 30 September 1961 (Paris 1961), no. 31

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 65

Tammaro De Marinis, Die italienischen Renaissance-Einbände der Bibliothek Fürstenberg (Hamburg 1966), pp.162-163

Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 4 (part set)

(11-12) Marcus Tullius Cicero, De philosophia, prima pars [-De philosophia volumen secundum] (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1552)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● unidentified owner, initials “P.J.O” (“P.J.C.” ) (Foot; see nos. 5-7 above)

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of printed books and a few manuscripts comprising the property of A.R. Goldie, Esq. … also a further selection from the library of the Right Hon. Lord Vernon, Sudbury Hall, Derby, London, 19-21 October 1921, lot 304 (in set of 8 volumes)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£25 15s; in set of 8 volumes); their Catalogue 489: Book bindings : Historical & decorative (London 1927), item 247 (set of eight volumes, £42 10s) [link]

● Jacques Rosenthal, Munich; their Katalog 93: Frühe Holzschnittbücher, Druckwerke des XVI. Jahrhunderts, spanische Bücher vor 1650, schöne Einbände (Munich 1930), item 604 (illustrated; price RM 1800; in set of 8 volumes) [link]

● Libreria antiquaria T. De Marinis & C., Florence [see above]

● Martin Breslauer, London; their Catalogue 67: One hundred fine books on many subjects (London 1949), item 28 (£780; in set of 8 volumes); Catalogue 71: A selection of fine books & manuscripts (London 1950) item 22 (£780; in set of 8 volumes) [Breslauer subsequently broke up the set into five parts: (1) Epistolae ad Atticum 1551; (2) De Philosophia 1552, in two volumes; (3) Epistolae familiares 1552; (4) Orationes 1550, in three volumes; (5) Rhetoricorum libri IV (and three other works) 1550]

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969), inscription in book, “23.viii.1950” (Foot)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 198 (“in the centre of the sides the device of a phoenix of Gabriele Giolito … Copies of Homer, Plutarch and Vittoria Colonna’s Rime are known bound with the same device. This was once attributed to Vittoria Colonna, who used a phoenix emblem, but as she died in 1547 before any of the books were printed it seems more likely that they once belonged to Gabriele Giolito, the Venetian printer, who first used this device in a book printed in 1542.”)

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£340)

● Henry Davis (1897-1977)

● British Library, Henry Davis Gift 809-810

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 4 (part set)

Mirjam Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: A Collection of bookbindings, volume 3: A Catalogue of South-European bindings (London 2010), no. 327

British Library, Database of Bookbindings, image [link]; image of Davis 809, [link]

(13) Vittoria Colonna, Rime (Venice: Bartolomeo & Francesco Imperatore, 1544), bound with: Vittoria Colonna, Le rime spirituali (Venice: Comin da Trino, 1548)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● Franco Moroli, of Rome

● Libreria antiquaria T. De Marinis & C., Florence

● Libreria Antiquaria Ulrico Hoepli, Manoscritti, incunabuli, legature, libri figurati dei secoli XVI e XVIII: Terza parte della collezione De Marinis, Milan, 17-19 June 1926, lot 286 & Pl. 39

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.208(int.1) (opac Legatura in pelle. Piatti decorati con figure geometriche concentriche e motivi fitomorfi a secco. Al centro dei piatti, emblema non identificato: ovale abitato da aquila con ali spiegate volta al sole su anfora. Dorso a 3 nervi.; image [link])

literature

Mostra storica della legatura artistica in Palazzo Pitti (Florence 1922), no. 241 (“Pelle rossa, compartimenti di filetti dorati e a freddo, nel mezzo la fenice adoperata nelle edizioni dei Giolito. (Signor Franco Moroli, Roma)”) [link]

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 910 & Tav. 153

Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 2

(14) Homerus, Batrachomyomachia odysseae homeri libri XXIIII (Basel: Johann Oporinus, 1549)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● Arthur Lauria, Paris; their Catalogue 31: Livres rares (Paris 1932), item 236 (“Jolie reliure avec les armes de l’Éditeur Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari”) & Pl. 8 (upper cover illustrated)

● Martin Breslauer, New York; their Catalogue 102 (London 1972), item 55 (“one of the rare bindings executed for the celebrated Venetian printer Gabriel Giolito de’Ferrari who used the phoenix device as his printer’s mark”; illustrated)

● Alberto Falck (1938-2003)

● Venice, Biblioteca Giustinian Recanati Falck

literature

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 911 (“Libreria A. Lauria 1932”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 (footnote 86, “not seen”)

Giulia Bologna, Legature: dal codice al libro a stampa; l’arte della legatura attraverso i secoli (Milan 1998), p.93

(15) Homerus, De nympharum antro in odyssea homericae quaestiones homericarum quaestionum liber homerika zetemata poieseis omeru ampho ete ilias kai e odysseia, hypo te iakobu tu mikyllu kai ioacheimu kamerariou paraskeuastheisai. Opus utrumque homeri iliados et odysseae, diligenti opera Jacobi mycilli & Joachimi camerarii recognitum (Basel: Johannes Herwagen, 1541)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● Genoa, Biblioteca Universitaria, 3.CC.VIII.14 (opac Legatura del sec. 16. in pelle marrone; decorazione in oro: filettature sia in oro sia a secco, cornice del tipo ‘Grolier’; dorso decorato sia in oro sia a secco con nome dell’autore; taglio dorato e inciso a motivi puntiformi e cordami) [link]

literature

Mostra di legature dei secoli XV-XIX, Genova, Palazzo dell’Accademia, 9 gennaio-3 febbraio 1976 (Genoa [1975]), no. 65 (“Pelle marrone rossiccio; sui piatti riquadrature filettate in oro e a secco, cornice a linee rette e curve del tipo ‘Grolier’, agli angoli piccoli ferri aldini pieni, al centro placchetta recante la figura della fenice; sul piatto anteriore, a secco, le lettere ‘SB, A’, appena visibili, forse impresse casualmente; dorso a nove nervi di differente spessore disposti alternativamente, decorato in oro e a secco e recante il nome dell’autore; dentelle filettate a secco; taglio dorato e inciso.”) [link]

Hobson, op. cit. 1999, p.127

(16) Plutarchus, Ethica sive moralia opera, quae in hunc usque diem de Graecis in Latinum conversa (Basel: Michael Isengrin, 1555)

provenance

● unidentified owner using a stamp of a phoenix

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.10 (opac Sulla risguardia anteriore, a matita ‘Cipriani’. Sul recto della carta di guardia anteriore, a matita, ‘Importante legatura con marca dell’editore Giolito de Ferrari. Legatura in stile Panevari [sic]’. Sul frontespizio, nel titolo, cancellato ad inchiostro ‘Iano Cornario’. Alcune voci nell’Indice sono cancellate”; “Legatura in pelle. Piatti decorati da cornici a filetto dorate. Nello specchio, ovale abitato da Fenice, rivolta al sole, su fiamme che si sprigionano da un’anfora. Taglio goffrato e dorato”)

literature

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 913

Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.97 no. 3

appendix – bindings with versions of device of the gioliti

(a) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarcha con l’espositione d’Alessandro Vellutello di nouo ristampato (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de Ferrari, 1545)

provenance

● unidentified owner using the publishers’ device of the Gioliti

● Modena, Biblioteca Estense, α 2. 9

literature

Giuseppe Fumagalli, L’arte della legatura alla corte degli Estensi, a Ferrara e a Modena, dal sec. XV al XIX. Col catalogo delle legature pregevoli della Biblioteca Estense di Modena (Florence 1913), no. 255 and Tav. IX (“Legatura officinale dei Gioliti, a piccoli ferri con l’impresa Giolitiana della Fenice. In marr. rosso. piatto posteriore”)

Domenico Fava, Catalogo della mostra permanente della R. Biblioteca Estense (Modena 1925), no. 377 (“Legatura dei Giolito, come dimostra la Fenice rinascente dalle fiamme, che ne era la marca tipografica, impressa nel centro del piatto posteriore.”)

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Trésors des bibliothèques d’Italie, IVe-XVIe siècles (Paris 1950), no. 366 (“Reliure vénitienne en maroquin rouge avec décor de petits fers dorés. Encadrement à motifs floraux et étoiles. Au centre du plat supérieur, Cupidon tirant de l’ac; au centre du plat inférieur, Phoenix renaissant des flammes, marque typographique de Giolito. Tranche dorée. Il s’agit probablement d’une reliure d’editeur.”)

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 1327 & Pl. 228

Anthony Hobson & Leonardo Quaquarelli, Legature bolognesi del Rinascimento (Bologna 1998), p.28 no. 10 (“Con un Cupido in atto di scagliare una freccia su un piatto (come sul n. 3) [the 1522 Aldine Plautus, ex-Abbey sale, 21-23 June 1965, lot 551; now Texas, Uzielli 178]”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1999, p.127 (as a Bolognese binding by the “Binder of Ulrich Fugger’s Bible”, “presumably produced for the [Giolito] branch in that city”)

(b) Suetonius, De vita Caesarum (manuscript written in 1433 in Milan by the scribe Milanus Burrus)

provenance

● unidentified owner using the publishers’ device of the Gioliti

● unidentified owner, armorial insignia flanked by initials “I” and “O” (Shipman, “At the foot of folio 4 are the arms of the person for whom the manuscript was made, a red cross on a dark brown ground, and on each side the initials ‘I’ and ‘O’ in gold”)

● Clarence S. Bement (1843-1923)

● Robert Hoe (1839-1909)

● Anderson Auction Company, Catalogue of the library of Robert Hoe of New York. Part II, New York, 15-19 January 1912, lot 2511 (“in a 16th century Italian binding of dark brown morocco, the sides tooled and gilt in compartments, in the centre of both covers the device (the phoenix) of Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari, the well-known printer”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($325)

● Phoebe A.D. Boyle

● Anderson Galleries, The magnificent library of the late Mrs. Phoebe A.D. Boyle of Brooklyn, N.Y., New York, 19-20 November 1923, lot 323 (“with the arms of Gabriel Giolito, the printer of Ferrara, on both covers; gilt gauffered edges”)

● Grenville Kane (1854-1943)

● Princeton, NJ, Princeton University, Kane MS. 44

literature

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Loan collection of decorative bindings, rare books, manuscripts, and other bibliographical specimens from the libraries of Philadelphia (Philadelphia 1893), no. 165 (“Clarence S. Bement … This classical manuscript is on vellum, executed in 1433, by Milanus Burrus. It is in the original morocco binding of the sixteenth century.”) [link]

Carolyn Shipman, A catalogue of manuscripts forming a portion of the library of Robert Hoe (New York 1909), pp.168-171 (“old dark brown Italian binding with side panels and ornaments in gilt, the arms of Gabriel Giolito (fl. about 1540-1560), the printer of Ferrara, on both covers”)

Exposition du livre italien Mai-Juin 1926 (Paris 1926), no. 201 (“Reliure de Gabriele Gioliti avec son emblème … A M. Grenville Kane, New York”)

B.L. Ullman, “Latin Manuscripts in American Libraries” in Philological Quarterly 5 (1926), pp.152-156 (p.156: “Tuxedo Park, N.Y. Grenville Kane collection … written by Milano Burro, probably in Florence. Binding shows device of Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari (1530-1560). This is the manuscript included by de Ricci as being in the Robert Hoe sale. From the library of Guiniforti de la Croce. A duplicate of the volume written by the same scribe in 1443 is in the Fitzwilliam Museum…”)

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 2155 & Pl. C43

Georges Colin, “Les marques de libraires et d’éditeurs dorées sur des reliures” in Bookbindings & other bibliophily: Essays in honour of Anthony Hobson (Verona 1994), pp.76-115 (p.100)

Hobson, op. cit. 1999, pp.127-128 & Fig. 77 (“may be from Ferrara”)

Don C. Skemer, Medieval & Renaissance manuscripts in the Princeton University Library (Princeton 2013), II, pp.99-102 (“the manuscript was owned by the Venetian printer Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari, whose initials and crest are on the binding”)

(c) Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1556)

provenance

● unidentified owner using the publishers’ device of the Gioliti

● unidentified owner, initials gauffered on fore-edge, “IC : MP” (“IMP”?)

● J. & J. Leighton, London; their Early printed books arranged by presses, [Part I] (London [1916?], item 1378 (£28; “contemporary Italian red mor., richly gold tooled sides with interlacing lines and arabesques; in centre a black oval inlay with device of a phoenix in silver (black) and gold; rebacked and corners slightly repaired, gilt gauffred edges, with initials of original owner Ic M P interlaced (slight wormhole in some leaves, but large and sound): enclosed in case”)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the third portion of the famous stock of the late Mr. W. J. Leighton (who traded as Messrs. J. & J. Leighton), of 40 Brewer Street, Golden Square, W. (sold by order of the Executor), London, 27-30 October 1919, lot 1962 (“contemporary Italian red morocco, richly gilt, side tooled with interlacing lines and arabesques, in centre a black oval inlay with device of phoenix in silver (black) and gold, gilt and gauffered edges, with initials of original owner IC : MP interlaced, rebacked and corners repaired, enclosed in a padded case”)

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale; their Catalogue 4 (new series): A Selection of notable books of interest for their subject, typography, decoration, binding, or illustration (London [1920?]), item 9 (illustrated; “beautiful example of contemporary Italian red moro., richly gold tooled sides with interlacing lines and arabesques; in centre a black oval inlay with device of a phoenix in silver …”)

● Manuel Alves Guerra, 2nd Visconde de Santana (1834-1910)

● D. De Winter & Librairie A. Louis de Meuleneere, Catalogue de la Bibliothèque de Monsieur le Baron de Sant’ Anna, Brussels, 16 May 1925, lot 106 (“Reliure à la Marque de l’Editeur Ferrari”) & p.82 (illustration) [link]

● Federico Gentili Di Giuseppe (1868-1940) [married Emma de Castro, with whom he had Marcello (b. 1901) and Adriana (b.1903).

● Adriana Raphaël (née Gentili di Giuseppe) Salem (1903-1976) [deposited the Gentili di Giuseppe collection in the Houghton Library; books subsequently purchased from her by Ward M. Canaday, Harvard College class of 1907, who gifted some to Harvard and sold others]

● Cambridge, Harvard College, Houghton Library, *IC5 Ar434 516o 1556c (opac Venetian binding of full red morocco, gilt, with center medallions inlaid in black on covers; edges gauffered & gilt)

literature

Dorothy E. Miner, The history of bookbinding 525-1950 AD, catalogue of an exhibition in cooperation with the Baltimore Museum of Art, 12 November 1957-12 January 1958 (Baltimore 1957), no. 233 (“edges gilt and gauffered, tooled with initials IMP, or a similar monogram”)

De Marinis, op. cit. 1960, no. 2270 (“mar. rosso; ricca dec. dorata; la pera vi è ripetuta quattro volte; al centro della targa si vede la Fenice. Alcune parti della legatura sono mosaicate di verde”; located “Paris, madame G. Salem”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1999, pp.127-128 & Fig. 78 (“by an otherwise unknown [Venetian] shop … in imitation of the Fugger binder”)

(d) Question de amor de dos enamorados: al vno era muerta su amiga, el otro sirue sin sperança de galardón (Venice: Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari & Fratelli, 1553 [1554])

provenance

● Domenico Tordi, Florence (1857-1933) [cf Alan Bullock, Il Fondo Tordi della Biblioteca nazionale di Firenze: catalogo delle appendici (Florence 1991): “Alla sua morte, nel 1933, la suddivise tra la Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, la Biblioteca Comunale “Luigi Fumi” di Orvieto e altri istituti.”; no copy of this book at Florence or Orvieto is reported to Edit16]

literature

Salvatore Bongi, Annali di Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari (Rome 1890-1895), II, p.471 (“Correzioni ed aggiunte … Vol. I. pag. L. … Di che ne dà quasi certezza il trovarsene alcuna dove è espresso sui piatti, stampato in oro, il segno caratteristico della fenice. Tale e la copia della Question d’Amor edita il 1551, posseduta dal sig. Domenico Tordi di Firenze, che cortesemente ce ne mandava la fotografia.”)

Hobson, op. cit. 1999, p.129