Bindings with the impresa “Scilicet is superis labor est”

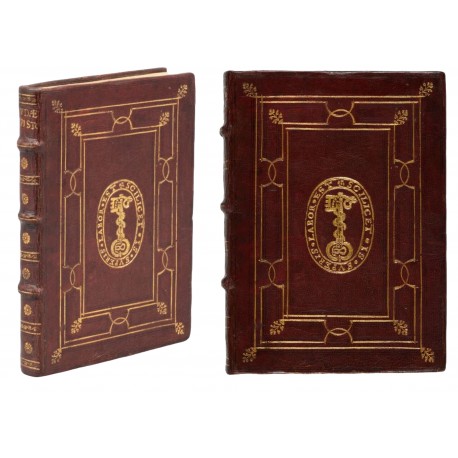

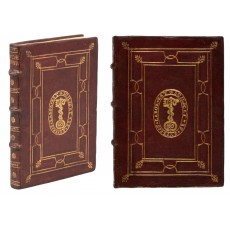

Nineteen bindings are now recorded with the impresa of a serpent entwined around a key, with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est” (For sure, this is work for gods - Vergil, Aeneid, 4.379), stamped in gold in the centres of both covers. Inside are books in Latin printed between 1517 and 1566, at Basel, Cologne, Florence, Lyon, Mondovì, Paris, and Venice, with Lyonese and Venetian imprints predominating. Two stamps were made, one (66 x 48 mm) for duodecimos and octavos, the other (91 x 68 mm) for books in quarto and folio format. The decoration is restrained: on the larger books, a frame composed of multiple gilt lines, with either a fleuron or fleur-de-lys at the corners; on the smaller ones, a frame containing foliage, with the same fleur-de-lys in corners. Red goatskin is employed for modern authors, olive or brown goatskin for ancient authors and ancient subjects. Each volume has a title lettered in the upper compartment, or vertically down the spine, suggesting how the books were displayed in their owner’s library.

Left Small stamp (66 x 48 mm) [no. 12] – Right Large stamp (91 x 68 mm) [no. 9]

The bindings attracted the eye of Guglielmo Libri, who collected three, recognising them as Italian bindings, albeit with a device appearing in Claude Paradin’s collection, Devises heroïques (Lyon 1557). E.P. Goldschmidt, who recorded two, thought the bindings might be Lyonese.1 By 1934, seven bindings were known to G.D. Hobson, who ventured that they were “probably Roman”.2 Anthony Hobson listed ten bindings in 1953, declaring them to be “unquestionably Roman” and, in view of the high proportion of books printed north of the Alps, speculating that they belonged to a foreigner, perhaps a Frenchman residing in Rome.3 By 1980, Hobson had reconsidered. His investigation of the libraries of the patrician families of Genoa, that of Giovanni Battista Grimaldi in particular, led him to believe that the owner was a Genoese nobleman.4 In 2012, Hobson delivered the name of a likely owner, Tommaso Franzone, and provided an updated list of 17 books (in 18 volumes) decorated with the coiled-snake device.5 (A 19th volume is added in the list below.)

Tommaso di Gaspare Franzone (d. 1627) belonged to the entrepreneurial “new” nobility of Genoa. He revived the family’s fortunes through astute participation in the silk trade and laid the foundations for their subsequent social ascent, serving twice as senator, and ensuring that his sons Agostino (1573-1658) and Anfrano (d. 1621) married into old families and held public offices. In 1602 he commenced building a villa in Albaro and in 1606 bought the Palazzo di Nicolò Spinola in via Luccoli.6

Hobson assumes that the coiled-snake bindings were made for Tommaso in the mid-1560s, some ten years after the Genoese banker and financier, Giovanni Battista Grimaldi (1524?-1612), had installed his library of about 200 volumes in a newly built villa near Genoa. Comparing Grimaldi’s bindings, adorned with the famous plaquette of “Apollo & Pegasus”, with the coiled-snake bindings, Hobson notes striking similarities: the Franzone and Grimaldi bindings both utilise impresa blocks of two sizes, both have spine titling in the same positions, both follow an eccentric colour scheme (red goatskin for modern authors, olive for ancient), and although bound twenty years apart in different shops, both have certain technical and decorative features in common. Hobson believes that Grimaldi’s library inspired Tommaso, and that in bibliophilic matters Tommaso was Grimaldi’s protégé. He adduces as evidence of that relation a book from Grimaldi’s library which contains Tommaso’s signature.7 Moreover, three of the recorded coiled-snake bindings were once in the possession of Anfrano Mattia di Gaspare Franzone (1646-1679), Tommaso’s great-grandson.8

The small number of tools on the coiled-snake bindings have not allowed identification of the binder. Hobson found no tools in common with those in the kit of the local Grimaldi Binder, and could not exclude the possibility that the shop was located elsewhere.9

1. S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson, Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri, London, 1-15 August 1859, lots 2036 (Pigna), 2558 (Suetonius), 2748 (Vico). E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author’s collection (London 1928), no. 247 (Macrobius).

2. Geoffrey Hobson, in Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, autograph letters & literary manuscripts, London, 1-3 August 1934, lot 291.

3. Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J. R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), p.136 no. 66, p.182 (Appendix D: Bindings with the same impresa as no. 66, Scilicet is superis labor est).

4. Anthony Hobson, “La biblioteca di Giovanni Battista Grimaldi” in Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria 20 (1980), pp.108-119 (p.118: “Il possessore è ancora da identificare. Bisognerebbe cercarlo fra i nobili genovesi che facevano costruire delle ville suntuose intorno agli anni 1560-1565.”).

5. Anthony Hobson, “A Genoese book collector” in Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 2012, pp.208-212.

6. Giuseppe Odoardo Corazzini, Memorie storiche della famiglia Fransoni (Florence 1873), pp.42-44.

7. Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: an enquiry into the formation and dispersal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), no. 69.

8. Nos. 10 (Macrobius), 12 (Thomas More), 15 (Ptolomaeus). Anfrano Mattia, the son of Gaspare di Anfrano di Tommaso (d. 1657) and Maria Maddalena Sauli, donated 50 books to the Augustinian friar Lodovico Aprosio’s Bibliotheca Aprosiana, the first public library of Liguria (ed. Hamburg 1734, pp.71-80).

9. For the Grimaldi Binder, see Hobson, op. cit. 1975, pp.97-100.

list of bindings

(1) Rodolphus Agricola, Rodolphi Agricolae lucubrationes aliquot lectu dignißimae (Cologne: Johann I Gymnich, 1539)

“Olive goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Sotheby’s, Catalogue of fine bindings and valuable printed books, London, 28 February 1966, lot 86 (“This hitherto unrecorded binding is the eleventh known with this impresa, which is taken from Claude Paradin’s Devises heroïques, Lyons, 1551. The motto is from the Aeneid, IV, 379. The owner of these bindings has not been identified, but the high proportion of northern imprints, together with the origin of the impresa, suggest that he may have been a Frenchman in Rome.”) [RBH TUNIS-86; this is the Stephen Mendl sale, but the lot is offered among “Other Properties”]

● Georges Heilbrun, Paris - bought in sale (£160)

literature

Anthony Hobson, “A Genoese book collector” in Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 2012, pp.208-212 (no. 2)

(2) Guillaume Budé, Epistolae Gullielmi Budaei, secretarii regii, posteriors (Paris: Josse Bade, March 1522), bound with Giovanni Battista Giraldi, Cinthii Ioan. Baptistae Gyraldi nobilis Ferrariensis Orationes (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de Ferrari & fratelli, 1554), bound with Lorenzo Conti, Orationes duae, ad illustrem virum Baptistam Grimaldum Hieronymi F. (Mondovì: Leonardo Torrentino, 1566), bound with Signorino Cuttica, Oratio de optimis studiis habita in Academia Montis Regii MDLXIII (Mondovì: Leonardo Torrentino, March 1564)

“Red goatskin (faded)” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● unidentified owner, inscription “pecia” on title of second text (cropped) (16C)

● unidentified owner, deleted inscription “Car… Julii Mul… R…” on upper endleaf (17C)

● Librairie Thomas-Scheler, Paris; their Livres précieux du XVe au XIXe siècle: XXIIe Biennale des Antiquaires: Paris, Carrousel du Louvre (Paris 2004), item 5 (€18,000) [RBH 04-005]

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 2004) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2035; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Magnificent Books and Bindings, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 22]

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 17

(3) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Officiorum libri tres. Cato maior, vel De senectute. Laelius, vel De amicitia. Paradoxa stoicorum sex. Somnium Scipionis, ex libro sexto De republica (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1552)

Colour of binding not reported by Hobson

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Libreria Antiquaria Bourlot, Turin, 1969

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 8

(4) possibly Marcus Tullius Cicero, Epistolae ad Atticum (Venice: Paolo Manuzio, 1563)

Colour of binding not reported by Hobson

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● unidentified owner, upper cover illustrated in Wieland: Deutsche Monatsschrift, V. Jahrgang (1920), Heft 3, p.21 [link]

literature

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J. R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), Appendix D, no. 9

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 15 (“binding reproduced in Wieland …with the place and date of printing, but no indication of the text. It probably then belonged to the German book trade”)

(5) Giovanni Della Casa, Latina monimenta. Quorum partim versibus, partim soluta oratione scripta sunt (Florence: Heirs of Bernardo I Giunta, 1564), bound with Jacopo Sadoleto, De laudibus philosophiae libri duo (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1538), bound with Étienne Dolet, Carminum libri quatuor (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1538)

“Olive-brown goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● inscription, “Mr Annesley” on pastedown (Foot)

● Sydney Richardson Christie-Miller (1874-1931)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a collection of rare and valuable books and tracts chiefly Latin, French and Italian of the XVth and early XVIth centuries, London, 31 July-3 August 1917, lot 287 (“contemporary Italian brown morocco, line tooled, with corner fleurons, device of a key entwined by a serpent with motto ‘Scilicet is superis labor est,’ plain edges”) [RBH Jul311917-287]

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£5 10s)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the first portion of the famous stock of the Late Mr. W.J. Leighton (who traded as Messrs. J. & J. Leighton), London, 14-19 November 1918, lot 193 (“contemporary Italian brown morocco, line-tooled with corner fleurons, device in gold of a Key entwined by a Serpent with motto ‘Scilicet is superis labor est,’ in centre, plain edges, enclosed in a new cloth box” [link])

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£4 15s); their Catalogue 380: Manuscripts and early printed books (London 1919), item 1914 (“contemporary Italian brown morocco, line-tooled with corner fleurons, device in gold of a Key entwined by a Serpent with motto ‘Silicet is superis labor est,’ in centre”) [RBH 380-1914]; Catalogue 395: Manuscripts, incunables, woodcut books and books from early presses (London 1920), item 318 [link]; Catalogue 437: Books on art and allied subjects (1923), item 408 (£10 10s) [link]; Catalogue 489: Book bindings: historical & decorative (London 1927), item 243

● Jacques Rosenthal, Munich; their Katalog 93: Frühe Holzschnittbücher, Druckwerke des XVI. Jahrhunderts, spanische Bücher vor 1650, schöne Einbände (Munich 1930), item 609 (M 500) [link]

● Martin Breslauer, London

● Henry Davis (1897-1977), purchased 1956

● London, British Library, Henry Davis Gift 840

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 10

Mirjam Foot, The Henry Davis gift: a collection of bookbindings, 3: A catalogue of South-European bindings (London 2010) no. 335

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 16

British Library, Database of Bookbindings, link

(6) Eusebius Pamphilius, Eusebii pamphili caesariensis, viri ut sanctissimi, ita multiuaria rerum & divinarum, & humanarum cognitione clarissimi opera (Basel: Heinrich Petri, [1549])

“Olive goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, autograph letters & literary manuscripts, London, 1-3 August 1934, lot 291 (“in the centre of each cover an oval emblematic stamp in gold, a serpent entwined round a key with legend ‘Scilicet is superis labor est’; back and corners repaired”) [RBH 01Aug1934-291]

● “East” - bought in sale (£4 10s)

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 4

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 6

(7-8) Marsilio Ficino, Opera et quae hactenus [in 2 volumes] (Basel: Heinrich Petri, 1561)

“Olive-green goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Genoa, Biblioteca Civica Berio, m.r.A.III.6.13 (1-2)

literature

Mostra di legature dei secoli XV-XIX, Genova, Palazzo dell’Academia (Genoa 1975), nos. 62-63 (“Legatura restaurata nel sec. XIX riportando il cuoio originale dei piatti; decorazione di filetti dorati diritti e ricurvi formanti cornice con al centro un medaglione ovale con impresa raffigurante una serpe che si attorciglia su di una chiave e intorno il motto: ‘scilicet is superis labor est’; dorso” [link])

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 13

(9) Paolo Giovio, Pauli Iouii Nouocomensis episcopi Nucerini Elogia virorum bellica virtute illustrium veris imaginibus supposita, quae apud Musaeum spectantur (Florence: Lorenzo Torrentino, 1551)

“Red goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Henry Benjamin Hanbury Beaufoy (1786-1851)

● Christie Manson & Woods, Catalogue of a portion of the valuable library of books & manuscripts formed during the early part of the last century by Henry B.H. Beaufoy, Esq. and now sold by order of the Beaufoy Trustees, London, 7-17 June 1909, lot 1138 (“red morocco extra, with device on sides”)

● Bull - bought in sale (5s)

● Nathaniel Evelyn William Stainton (1863-1940), Barham Court, Canterbury

● Mrs. Evelyn Stainton (Harriet Wilhelmina (née Grimshaw) (1887-1976)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of a library of printed books, manuscripts and fine bindings; the property of Mrs. Evelyn Stainton, Barham House, Canterbury, London, 26-27 February 1951, lot 145 (“in a Roman red morocco binding of about 1565, border of lines in gilt and blind, fleurons at comers, in the centre of each cover a large device of a serpent coiled round a key, surrounded by the motto, scilicet is superis labor est, r. e. … Only nine other bindings are known with this device, the latest covering a book printed in 1564. The collector for whom they were executed has not been identified; he may have been a Frenchman living in Italy.”) [RBH Tree 145]

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£20)

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the celebrated library, the property of Major J.R. Abbey, Part III, London, 19-21 June 1967, lot 1948

● Braithwaite - bought in sale (£120)

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, no. 66 and Appendix D, no. 6

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 7 (“Private collection”)

(10) Ambrosius Aurelius Theodosius Macrobius, In somnium Scipionis, libri II. Saturnaliorum, libri VII. Ex variis, ac vetustissimis codicibus recogniti et aucti (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1556)

“Olive-green morocco” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Martino Protis, inscription “Ex copietis (?) Martini Protis” on endpaper (Foot; Hobson 2012 p.212, “ex codicibus”) [compare nos. 12, 15 below]

● inscription “Harry Trelawny 1715” (Foot; probably Harry Trelawny, 1687-1762, of Whitleigh, Devon, A.d.c. to Duke of Marlborough in 1706, M.P. 1708-1710)

● Augustus Frederick, Royal Duke of Sussex (1773-1843), armorial exlibris

● Charles Isaac Elton (1839-1900)

● Mary Augusta (née Strachey) Elton (1838-1914)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the valuable library of books & manuscripts of the late Mrs. Charles Elton, London, 1-2 May 1916, lot 335 [link]

● Librairie Théophile Belin, Paris - bought in sale (£3)

● Gilhofer & Ranschburg, Vienna

● E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., London [E.P. Goldschmidt stockbook, entry #1545, as purchased 1 October 1923]; their Catalogue 75: A Selection of books of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (London 1944), item 96 [RBH 75-96]

● Henry Davis (1897-1977)

● London, British Library, Henry Davis Gift 814

literature

E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author’s collection (London 1928), no. 247

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 7

Foot, op. cit., III, no. 334

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 10

British Library, Database of Bookbindings, link

(11) Paolo Manuzio, Pauli Manutii Epistolae, et praefationes quae dicuntur (Venice: Accademia Veneziana, 1558)

“Red goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● “MS letters on title-page recto: illegible” (opac)

● George John, 2nd Earl Spencer (1758-1834)

● Manchester, John Rylands Library, 5980 (opac Sixteenth-century Italian[?] full red goatskin; gilt and blind-tooled fillets to form a panel with corner fleurons; on upper and lower boards: large oval in gilt of a key entwined by a serpent with motto ‘Scilicet is superis labor est’; five raised bands to spine; direct-lettered in gilt vertically: Pav. Man. Epist. [link])

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 12

John Rylands Library, Digital collections (luna), link

(12) Thomas More, Ad lectorem. Habes Candide Lector opusculum … Thomae Mori … de Optimo reipublice statu deque nova insula Utopia (Paris: Gilles de Gourmont, [ca 1517])

“Red goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● inscription “Anfranus matthias fransonus” on title-page, inscription (monogram) AMF on title-page (Foot)

● Martino Protis (Hobson 2012 p.212) [compare nos. 10, 15]

● Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery (1847-1929), exlibris

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the well-known and very valuable library formed at Durdans, Epsom, by the late Rt. Honble. the Earl of Rosebery, K.G., K.T., sold by order of his daughter Lady Sybil Grant, London, 26-30 June, 1933, lot 922 (“old red morocco (? c. 1565), panelled sides with oval emblematic stamp in gold in centre, a serpent entwined round a key with legend “scilicet is superis labor est,” joints repaired … Only five other books with this device are known” [link]) [RBH 26Jun1933-922]

● E.P. Goldschmidt, London - bought in sale (£34)

● Lucius Wilmerding (1880-1949), exlibris

● Parke Bernet Galleries, Rare XV-XIX Continental literature … Part II of the important library belonging to the estate of the Late Lucius Wilmerding, New York, 5-6 March 1951, lot 469 (“monogram AMF written on the title-page … Two manuscript exlibris on fly leaf”) [RBH 1230-469]

● Henry Davis (1897-1977)

● London, British Library, Henry Davis Gift 813

literature

The Italian book, 1465-1900: Catalogue of an exhibition held at the National Book League (London 1953), p.90 no. 269

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 1

Foot, op. cit., III, no. 333

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 1 & Fig. 1

British Library, Database of Bookbindings, link

(13) Giovanni Battista Pigna, Io. Baptistae Pignae Carminum lib. quatuor (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1553)

“Red goatskin” (Hobson) [covers laid into new structure, rebacked; 19C endpapers]

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Tirnoleone, Count Libri (Libri-Carrucci| (1803-1869)

● S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson, Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri, London, 1-15 August 1859, lot 2036 (“in old red morocco, ornamented sides, having for the centre, stamped in gold, a Serpent twined round a key, surrounded by the motto Scilicet is superis Labor Est” [link])

● Bumstead, London - bought in sale (£1 10s), his (?) pencil inscription on lower pastedown: “No 2036 Libri’s sale Aug 1859 | £ [code in pounds and shillings, no pence] + commission | C & P | CDG”

● unidentified owner [catalogue entry pasted to front free endpaper, heading “Binding - Io. Baptistae Pignae Carminum lib. quatuor … bound in morocco, with curious device on title (see note), £3 3s [same price in pencil, opposite] The collector whose device – a serpent twined round a key surrounded by the mottos ‘Scilicet is superis, labor est’ – is impressed on the sides of the above volume cannot be identified, and it is not known to what family the arms belong. There were one or two books bearing the same device in the Libri collection which sold for good prices. The idea must have been taken from Claude Paraden’s [sic] Book of Emblems, published in 1551, from which a facsimile of this device is given in Dibdin’s Decameron, Vol. I, p.269.”]

● British Museum, date acquisition stamp 18 July 1900 on last page

● London, British Library, C.67.b.13

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 2

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 9

British Library, Database of Bookbindings, link

(14) Platina (Bartolomeo Sacchi), Opus de vitis ac gestis summorum pontificum, ad sua usque tempora deductum, et auctum deinde accessione rerum gestarum eorum pontificum, qui Paulo II (Cologne: Maternus Cholinus, 1562)

“Red goatskin (faded)” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● unidentified owner, inscription “Rdus D. Barth. Axentus Curatus Cassani” on title-page

● Congregazione della Missione (San Vincenzo De Paoli), Casale Monferrato, circular inkstamp “Missionis domus Cong. Casalensis”

● unidentified owner, inscription “Fantinetti ex Eppido Riguilorum” on upper pastedown

● unidentified owner(s), shelfmarks “B11” (deleted) and “Scania A.12” (18C?)

● unidentified owner, armorial exlibris “Ex libris Dominici De Advocatis, comitis Odelli, equitis benensis” (20C)

● Guido Bortolani, Modena; their catalogue: Mostra del libro antico [Milan] 16-18 marzo 2001 ([Modena 2001]), p.42 item 54

● Librairie Thomas-Scheler, Paris

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 2005) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2325; to be offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part VII, London, 11 July 2025, lot 1805]

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 14

(15) Claudius Ptolomaeus, Geographicae enarrationis, libri octo. Ex Bilibaldi Pirckeymheri tralatione, sed ad Graeca et prisca exemplaria a Michaële Villanovano secundo recogniti (Lyon: Gaspard Trechsel for Hugues de La Porte, 1541)

“Olive-brown goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● inscription, “Anfranus Matthias Fransonus” [compare nos. 10, 12 above]

● Martinus Protus (Hobson 2012, p.212) [compare nos. 10, 12 above]

● Milan, Biblioteca nazionale Braidense, L.P.1 (opac, [link])

literature

Federico Macchi, Arte della legatura a Brera: Storie di libri e biblioteche, secoli XV e XVI (Cremona 2002), no. 29 (illustrated)

Federico & Livio Macchi, Atlante della legatura italiana: Il Rinascimento (XV-XVI secolo) (Milan 2007), pp.239-240 Tav. 98 (“Non si esclude possa trattarsi di un riutilizzo considerata l’abbondante unghiatura (7 mm ca.) del taglio di gola”)

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 4 & Fig. 2

(16) Jacopo Sannazaro, Opera omnia quorum indicem sequens pagella continet (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1540)

“Red goatskin” (Hobson)

Image courtesy of Federico Macchi

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Marchese Francesco Casati, inscription “ex libris Francisci Casati”

● Bartolomeo Casati, inscription “Ex libris Bartholomei Casati Placentini” [acquired by the Biblioteca Palatina between 1761 and 1785; Bartolomeo, the son of marchese Francesco Casati, lost the Castello della Boffalora and other assets in (bankruptcy) 1704]

● Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, BB IX.25956 (Inventario PAL 39488) (opac pelle; sui piatti filetti impressi a secco, filetti, decorazioni e stemma con motto (Scilicet is superis labor est) impressi in oro; sul dorso nervature, decorazioni, nome dell’A. e tit. impressi in oro [link])

literature

Mostra storica della legatura artistica in Palazzo Pitti (Florence 1922), no. 197 [link]

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 2

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 3

(17) Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, Duodecim Caesares, cum commentariis, et annotationibus (Lyon: Jean Frellon, 1548)

“Olive-brown goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone, Count Libri (Libri-Carrucci) (1803-1869)

● S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson, Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri, London, 1-15 August 1859, lot 2558 (“in the original Italian olive morocco binding of the XVIth century, with gold line-borders, having the fleur-de-lys at the corners, and in the centre the device of a serpent twining round and through a key surrounded by the motto ‘scilicet. is, superis. labor. est.” [link])

● Thomas & William Boone, London - bought in sale (£1 10s)

● London, British Library, C.47.k.14

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 3

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 5

British Library, Database of Bookbindings, link

(18) Enea Vico, Augustarum imagines aereis formis expressae: vitae quoque earundem breuiter enarratae, signorum etiam, quae in posteriori parte numismatum efficta sunt, ratio explicata: ab Aenea Vico Parmense (Venice: [Paolo Manuzio], 1558)

“Olive goatskin” (Hobson)

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone, Count Libri (Libri-Carrucci) (1803-1869)

● S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson, Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri, London, 1-15 August 1859, lot 2748 (“large paper, very rare, 4to. Venetiis, Aldus, 1558 A fine specimen of contemporary Italian binding in olive morocco, gilt edges, the sides richly ornamented, having as a centre the device of a serpent entwining a key, with the motto ‘silicet. is. superis. labor. est.’” [link])

● Techener, Paris - bought in sale (£3)

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1953, Appendix D, no. 8

Hobson, op. cit. 2012, no. 11

addition to hobson’s 2012 list

(19) Marcus Junianus Justinus, Ex Trogi Pompeii historiis externis libri XXXXIIII. His accessit ex Sexto Aurelio Victore de vita et moribus Romanorum imperatorum epitome (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1555)

Red goatskin

provenance

● Tommaso Franzone (d. 1627), supralibros, purported user of impresa with motto “Scilicet is superis labor est”

● circular inkstamp “Bibl. Patr. Dom. SJ - Milltown Park” on title-page

● Milltown Park College, Dublin

● James Fenning, Dublin [bookseller; firm established by his grandfather in the 1890s]

● Whyte’s, The James Fenning sale of antiquarian books, Dublin, 19-20 October 2012, lot 984 (“contemporary red morocco, the sides with both plain and gilt borders enclosing a large oval in gilt of a key with an entwined snake within the motto ‘Scilicet is superis labor est’ … gilt spine, lettered directly and vertically; with a small circular stamp on the title-page” [link])