Georg Römer’s Bindings

The books were published at Antwerp, Basel, Florence, Lyon, Nuremberg, Rome, Strasbourg, and Venice, in Latin, German, Italian, and Spanish. Those retaining the Römer exlibris were printed between 1517 and 1555, all but two in the narrower range 1548-1555; those books without an exlibris were printed in the years 1538-1557. The volumes appear to have been bound within a short period of time, but probably not as a single order. The preponderance of texts on Italian art and architecture, antiquities, ancient and modern history, suggested to Hobson that the collector was a refined Italophile (“a German Grolier”), who had undertaken a tour of Italy in the 1550s and on his return home commissioned bindings in an Italianate style.

Hobson’s candidate, Philipp Römer, was the third of four sons of Georg Römer (1505-1557) and Magdalena Welser (d. 1582). Born about 1543,2 he became in 1567 agent (Faktor) for the Fugger family in Antwerp, then in 1575 their agent in Nuremberg. In 1579, Philipp married the Augsburg heiress Eleonora Hörmann von und zu Guttenberg, and the following year was named to the larger city council (Genannter des Größeren Rats); he died on 15 January 1593. Although Philipp had regularly sourced works of art and luxury goods for Fugger family members, he is not known to have formed any personal collections.3

A more likely owner of these volumes is Philipp’s father, Georg (Jörg) Römer. Georg was born in 1505 at the Saxon town of Mansfeld (300km north of Nuremberg), studied at Leipzig (possibly with Petrus Mosellanus), and matriculated in 1519 at Wittenberg, where he was friendly with Luther, Melanchthon, and Joachim Camerarius.4 In 1525, Georg married in Nuremberg Magdalena Welser, sister of the wealthy merchant Jacob Welser, with whom he had ten children. He was appointed a court assessor and lay judge (Schöffe) in Nuremberg’s Landgericht and Stadtgericht, and became involved in public projects, including a renewal of the city’s fortifications in 1538-ca 1544, and the design of ephemeral architecture for the ceremonial entry of Ferdinand I as king of the Romans in 1540. In the former project, Georg participated as a translator between the Italian-Maltese architect Antonio Fazuni and local craftsmen, including his friend, Georg Pencz;5 in the latter, as designer of street decorations executed by Sebald Beck and Georg Pencz.6 The community of artists in Nuremberg was of great interest to Georg and in 1547 he commissioned from Johann Neudörffer a compendium of 79 local artists’ and artisans’ lives, the first such work written in German, which was circulated in multiple manuscript copies.7

Georg Römer was a passionate collector, particularly of coins and medals. While still a student, he commissioned three portrait medals,8 and by the mid-1540s he possessed a numismatic collection so noteworthy that Jacopo Strada,9 Hubert Goltzius,10 and Samuel Quiccheberg journeyed separately to see it.11 Among Georg’s most prized possessions were two genuine paintings by Albrecht Dürer, a bust-length Man of Sorrows and a self-portrait, and paintings by Cranach, Titian, Hieronymus Bosch, and Georg Pencz. Besides the numismatic collection, Georg apparently kept in his study an ancient Roman marble sculpture, maps, charts, and scientific instruments.12

The books in these twenty-odd bindings mirror Georg Römer’s known interests. His passion for coins and medals is represented by compilations of images of the Roman emperors retrieved from ancient coins, assembled by Andrea Fulvio, Johann Huttich, Guillaume Rouillé, and Jacopo Strada, and here bound-up in three volumes (nos. 5, 6, 12 in the List below), each containing the Römer exlibris. A copy of Onofrio Panvinio’s similar repertoire is in a matching binding, but has no exlibris; it was published in the year of Georg’s death (dedication dated Venice, May [1557]; Georg died 4 April 1557). A complementary book, Ammianus Marcellinus’s Roman history, retains the exlibris. Georg’s fluency in Italian, utilised during Fazuni’s rebuilding of the city walls of Nuremberg, and his interest in artist biographies, are manifested by the copy of Vasari’s compendium of artists’ biographies (with Römer exlibris), also by a copy of Cosimo Bartoli’s 1550 Italian translation of Leon Battista Alberti’s architectural treatise (without exlibris).

Above left Siebmacher [link] – Right Staehelin [link]

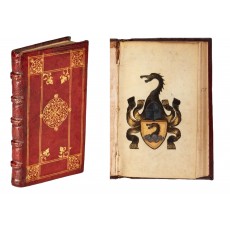

On 9 February 1554, Georg was granted a coat of arms.13 The shield is charged with a black ostrich (neck only), shown rising from a blue mountain (Dreiberg) and feeding on an iron horseshoe, with above a helmet, mantle, and crest of the same.14 Several versions of an exlibris displaying this insignia were made. The base of each is a printed woodcut outline, painted, and heightened with gold. Judging by available descriptions, it invariably appears on a leaf inserted by the binder at the front of the volume; in three volumes (nos. 1, 5, 7), that flyleaf is vellum. After Georg’s death, a new coat of arms was granted in the name of the abdicated Emperor Charles V; henceforth, the shield is quartered.15

Above left Rosenthal, Lobris sale catalogue, p.229 [link]

Centre Exlibris in No. 1 : Alciati

Right Exlibris in No. 12 : Rouillé

Georg Römer died on 4 April 1557.16 In his testament, he bequeathed his library including his maps and charts to his four sons (“alle Libereÿ sampt Mappen v. Charten den söhnen”), mandating them to keep it intact (“so sie vnzerstreut behalten sollen”).17 Philipp was the last of his sons to die, in 1593, after which the collections passed eventually to Georg’s daughter, Catherina. Following her death, in 1622, the contents of Georg’s study was dispersed.

Three volumes (nos. 1, 5, 12) soon entered the library assembled at Schloß Lobris in Silesia by Otto von Nostitz (1608-1665) and his son, Christoph Wenzel von Nostitz (1643-1712), where they received the latter’s distinctive armorial exlibris. After the death of Joseph Graf von Nostitz-Rieneck (1821-1890), Schloß Lobris passed through the marriage of his daughter Ernestine to the Wolkenstein-Trostburg family, and the library was removed.18 The Belon, Fulvio, Huttich and Rouillé (nos. 3, 5, 6, 12) were included in an auction sale conducted in 1895 by the bookseller Ludwig Rosenthal.19 Rosenthal took other books from Schloß Lobris into his stock, and the Alciati, Ammianus Marcellinus, Brandt, and Tarapha (nos. 1, 2, 4, 13) probably passed through his hands. A four-volume set of Livy (nos. 8-11), already in the trade in December 1892, could be evidence of an earlier disposal. Investigation of a manuscript catalogue of the Schloß Lobris library (8824 volumes) compiled in 1769 might help to decide the matter.20

Other volumes in the Römer library were more widely distributed. The Vasari (no. 14) contains in addition to the Römer exlibris the exlibris of Amadeo Svajer (1727-1791), a German merchant in Venice, whose library was sold there in 1794. Two volumes unaccompanied by the Römer exlibris, the Alberti and Petrarca (nos. 15, 25), were respectively in the libraries of Sir Andrew Fountaine (1676-1753), at Narford Hall, Norfolk, and Gian Giacomo Trivulzio (1774-1831) in Milan. These and five similar volumes without the Römer exlibris are linked to the Römer library only by their gilt decoration. Unless an inventory of the Römer books (or a similar document) should be discovered, the issue of whether they were bound for Römer family, or for another customer, will remain unresolved.

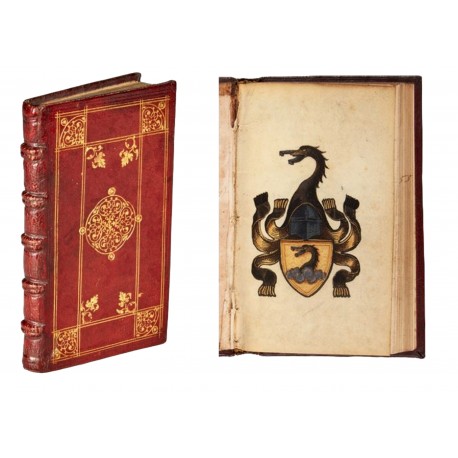

All the bindings in the group are tooled in gilt to a panel design, with an outer border formed by two sets of gilt double fillets, an openwork tool in the square formed at the angles, and leaves at the inner corners. The quartos have an inner border filled by one or the other of two rolls. A centrepiece is composed of four repetitions of the tool used at the outer corners. The similarity of the tool used for the cornerpieces and centrepiece to one deployed on Roman bindings of the mid-16th century is striking.21

Above left Nuremberg binding: Detail from No. 13 Tarapha

Centre Roman binding: Detail from BAV, Vat Lat 3537 [link]

Right Nuremberg binding: Detail from No. 22 : Neudörffer

Above left Roman binding: Detail from BAV, Vat Lat 3537 [link]

Centre Detail from No. 13 Tarapha

Right Roman binding: Detail from Paris, BnF, Italien 2324 [link]

Ilse Schunke credited the binding on the Panvinio (no. 19, without Römer exlibris) to the Nuremberg binder Christoph Heußler (Heusler, Häussler), without stating her grounds.22 Heußler had married in Nuremberg in 1541 and worked there as a printer from about 1556 until 17 February 1574, when he declared before the city council that he wished to cease printing, and continue exclusively as a binder; at the time of his death, 2 October 1578, he was chairman (Vorsitzender) of the bookbinders’ guild.23 A binding decorated by the same tools was hesitantly credited to Heußler by the Einbanddatenbank, citing Schunke. It covers a copy of Johann Neudörffer, Ein gute Ordnung und kurtze Unterricht (1538-ca 1543) (no. 23).24 Another copy of the same book, in the British Library, is decorated by the same tools (no. 22),25 as is one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (no. 24).26 Given Georg Römer’s strong friendship with the author, it could be that he arranged around 1549 to have several copies of the Gute Ordung specially bound.

In demonstrating the Nuremberg origin of the Römer bindings, Hobson illustrated a book bound about the same date in a similar style, for another Nuremberg family.27 A copy of the Syriac New Testament, edited by Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter (1555), it is decorated by the same roll and large corner ornaments; however, it has an oval mauresque plaque (49 x 38 mm) in the centres of its covers (no. 20). The Einbanddatenbank has credited this binding to an anonymous Nuremberg workshop (ebdb w007963).28 A manuscript written by the Nuremberg instrument maker Georg Hartmann (1489-1564) around 1527 (no. 21) is in a binding with a centrepiece composed of four repetitions in blind of an openwork tool.29 Judging from reproductions, this is the tool employed on the bindings made for Römer. A roll and a flower tool used for the inner corners are not used on the Römer bindings, and these tools cannot be traced in the Einbanddatenbank.

A problematic binding covers two books in Italian printed at Venice in 1561 and 1564, one a treatise on gambling, the other on viticulture (no. 26). Pasted to an endpaper of this binding is the painted exlibris Römer exlibris (version with angled shield). The material is red goatskin and the cover decoration consists of double frames of a single gilt between quadruple blind fillets, gilt leaf ornaments at the outer corners of each frame, with a centrepiece composed of four impressions foliate tool. The binding is demonstrably North Italian (perhaps Milanese), with characteristic division of the spine (3 full and 4 half-bands), the compartments filled with an arabesque tool in blind, the half-bands with gilt cross-hatching. None of the other recorded books from the Römer library is in an Italian binding, and it is notable also that the later of the two works inside was published seven years after the death of Georg Römer. It is possible that the Römer exlibris was removed from a different book and placed into this volume.

1. Anthony Hobson, “Some sixteenth-century buyers of books in Rome and elsewhere” in Humanistica Lovaniensia 34A (1985), pp.65-75 (pp.74-75) [link]. In 1965, when cataloguing Abbey’s copy of Vasari (see no. 14 in List), Hobson believed these bindings to be Roman.

2. A medal dated 1565 depicts him aged 22 (philippvs · roemer · nor ætatis svæ xxii), however the accompanying motto (femineo · imperio · mitescvnt · effera · corda: fierce hearts become gentle under feminine rule) suggests an older man; see Christoph Andreas Imhof, Sammlung eines Nürnbergischen Münz-Cabinets, Ersten Theils, zwote Abtheilung (Nuremberg 1782), pp.882-883 no. 17.

3. Sylvia Wölfle, Die Kunstpatronage der Fugger, 1560-1618 (Augsburg 2009), pp.21, 205, 284, citing Christl Karnehm & Maria Preysing, Die Korrespondenz Hans Fuggers von 1566 bis 1594 (Munich 2003), passim [link].

4. Georg Andreas Will, Commercium epistolicum Norimbergense, sive virorum celeberrimorum Norimbergensium ad diversos (Altdorf 1756), p.1 [link]. For Georg’s friendship with Melanchthon, see Heinz Scheible, Melanchthons Briefwechsel. Band 14 Personen O-R (Stuttgart 2020), pp.498-499. In 1538, Georg received the dedication of Camerarius’s anthology of Greek epigrams; see Jochen Schultheiss, “Profilbildung eines Dichterphilologen: Joachim Camerarius d.Ä als Verfasser, Übersetzer und Herausgeber griechischer Epigramme” in Meilicha Dôra: Poems and Prose in Greek from Renaissance and Early Modern Europe, edited by Mika Kajava, Tua Korhonen & Jamie Vesterinen (Helsinki 2020), pp.149-184 (pp.153-154) [link].

5. Thomas Freller, “The ‘unequalled artist and architect Senior Anthonio, il maltese’, pioneer of Renaissance architecture and military engineering in Europe” in Symposia Melitensia 11 (2015), pp.93-109 (p.100) [pdf online, link].

6. Heidi Eberhardt Bate, “Portrait and pageantry: New idioms in the interaction between city and empire in sixteenth-century Nuremberg” in Politics and Reformations: Communities, polities, nations, and empires (Leiden 2007), pp.121-141 (p.136).

7. Johann Neudörfer, Des Johann Neudörfer Nachrichten von Künstlern und Werkleuten daselbst aus dem Jahre 1547, edited by G.W.K. Lochner (Vienna 1875), pp.1-2 [link]; Hannah Saunders Murphy, “Artisanal ‘Histories’ in early modern Nuremberg” in Knowledge and the early modern city: a history of entanglements, edited by Bert De Munck & Antonella Romano (London 2019), pp.58-78 [online, link]. Lochner believed the autograph manuscript to be lost; an early copy, dated 1547, in the Germanisches National Museum in Nuremberg, Merkel HS 4° 533, is bound in paper boards [link]. If Georg placed the presentation manuscript in a fine binding, that copy has been lost.

8. Max Bernhart, “Medaillengeschichtlicher Beitrag zur Welserhistorie des XVI. Jahrhunderts” in Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft 30 (1912), pp.87-112 (pp.104, 110-111 nos. 24-26) [link]; Georg Habich, Die deutschen Schaumünzen des XVI. Jahrhunderts (Munich 1929), I/1, no. 8 (anonymous portrait medal, dated 1521); nos. 322-323 (portrait medals dated 1524).

9. Strada visited Georg sometime before November 1546; see Dirk Jansen, Jacopo Strada and cultural patronage at the imperial court (Leiden 2019), I, pp.81, 126.

10. Goltzius inspected the collection around 1563, by which date it was in the possession of Georg’s heirs; see Hubert Goltzius, C. Iulius Caesar sive historiae Imperatorum Caesarumque Romanorum ex antiquis numismatibus restitutae, Liber primus (Bruges: [Hubert Goltzius], 1563), sig. aa4v (“Haeredes Georgij Rhoemer, Patricicij; Norimbergensis”).

11. Quiccheberg also visited after Georg’s death; see The First Treatise on Museums: Samuel Quiccheberg’s Inscriptiones, 1565, translation by Mark Meadow & Bruce Robertson (Los Angeles 2013), p.101 (translation of original folio H1 recto: “I saw with great pleasure what was the Roemerian treasury at the home of Georg Roemer’s sons”).

12. Susanne Meurer, “A little-known collector and the early reception of Dürer’s self-portraits” in Burlington Magazine 162 (2020), pp.108-114.

13. Karl Friedrich von Frank, Standeserhebungen und Gnadenakte für das Deutsche Reich und die Österreichischen Erblande bis 1806 (Senftenegg 1973), IV, p.181 (“Römer, Georg, und Sohn Albrecht, Adelstand, Wappenbestätigung, Wappenbesserung, privil. fori, exemptio, Rottwachsfreiheit, Lehenberechtigung, privil. denominandi, Freisitzrecht, kaiserlich Schutz und Schirm, Salva Guardia, privil. de non usu, ad personam: Palatinat, Brüssel, 9, II. 1554 (Reichsakt)”). Cf. Julia Kahleyß, “Der wirtschaftliche Aufstieg des Martin Römer. Soziale Mobilität im westerzgebirgischen Bergbau des 15. Jahrhunderts” in VSWG: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 100 (2013), pp. 154-177 (p.163, citing Nuremberg, Stadtarchiv, E1/1452, Nr. 1).

14. W.R. Staehelin, “Der Vogel Strauss in der Heraldik” in Schweizerisches Archiv für Heraldik 39 (1925), pp.49-57 (p.55, with reproduction of the Römer insignia in the Baldung Armorial, Staatsarchiv Basel) [link].

15. The quartered shield appears on portrait medals of Georg’s widow and children, see Habich, op. cit., II/1, no. 2508 (Valentin Maler’s medal of Georg’s son Philipp, dated 1576); nos. 2506, 2528 (Maler’s medals of Georg II, dated 1576 and 1580); no. 2532 (Maler’s posthumous medal for Georg’s wife Magdalena, dated 1582). The same blason is shown in a woodcut by Jost Amman, in Stam und Wapenbuch hochs und niders Standt (Frankfurt am Main 1579), f.** verso [link]; cf. Johann Siebmacher, Grosses und allgemeines Wappenbuch, Sechsten Band, Erste Abtheilung: Abgestorbene Bayrischer Adel (Nuremberg 1884), p.88 & Tafel 88 [link].

16. Peter Zahn, Die Inschriften der Friedhöfe St. Johannis, St. Rochus und Wöhrd zu Nürnberg (Munich 1972), p.210 no. 846.

17. The original will is lost, however a summary record made by Jacob Wilhelm Imhoff survives (Nuremberg, Stadtbibliothek, Amb. 173.2°, fol. 225 r-v); see T. Renkl, “Albrecht Dürers Selbstbildnis von 1500. Der verzweigte Weg von Original, Kopie und Fälschung” in Mitteilungen des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Nürnberg 103 (2016), pp.39-89 (p.43, reproduced as Abb. 1); Meurer, op. cit., p.114 (transcription and English translation).

18. Heinrich Meisner, “Die Nostizische Bibliothek in Lobris” in Neuer Anzeiger für Bibliographie und Bibliothekswissenschaft (November 1875), pp.339-342 [link]; Colmar Grünhagen, “Ein archivalischer Ausflug nach Boltenhain, Jauer und Lobris” in Zeitschrift des Vereins für Geschichte und Alterthum Schlesiens 11 (1872), pp.344-358 (pp.354-358) [link]; Reinhard Wittmann, “Barocke Funde aus der Sammlung Nostitz” in Beiträge zu Komparatistik und Sozialgeschichte der Literatur: Festschrift für Alberto Martino (Amsterdam 1997), pp.591-614 [link].

19. Ludwig Rosenthal’s Antiquariaat, Bibliothek Lobris, Katalog der reichhaltigen Bibliothek des gräflichen Schlosses Lobris bei Jauer i/Schlesien und anderer Sammlungen, Munich, 22 April 1895 [link].

20. Prague, Nostitzbibliothek, Ms f 16: Catalogus librorum qui in bibliotheka illustrissimae familiae comitum de Nostitz et Rinek reperiuntur. Adcurante excellentissimo domino domino Francisco Antonio S. R. I. Comite de Nostitz et Rinek in numerum ac ordinem constituti A. A. E. V. 1769.

21. See Hobson’s entry for the Vasari in the Abbey sale catalogue, citing Tammaro de Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 918 & Pl. 110 (covers lettered Her[cules] Gon[zaga] Car[dinalis] Man[tuanus], i.e. for Ercole Gonzaga, 1505-1563, Cardinal from 1527; Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. lat. 3537); no. 638 & Pl. 114 (register of Tesoreria segreta of Pope Paul III, 2 November 1535-2 November 1538, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Italien 2324). [Paris Ms misdated by De Marinis, see link]; no. 456 & Pl. 86 (used in combination with gilt stamp of a lion with a ball beneath his paw).

22. Ilse Schunke, Die Einbände der Palatina in der Vatikanischen Bibliothek (Città del Vaticano 1962), I, pp.132-133 (line drawing of upper cover).

23. Josef Benzing, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet (Wiesbaden 1963), p.347; Christoph Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet (Wiesbaden 2015), pp.750-751.

24. The book is in Nuremberg, Bibliothek des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, Postinc. 8° W.954 (formerly Nr. 7594; opac, link). The upper cover is lettered “s w g d m d | v i n i n e | 1549” and the lower cover “h i b | 1590”. See Katalog der im germanischen Museum vorhanden interessanten Bucheinbände (Nuremberg 1889), p.70 no. 280 (“Pappband mit braunem, goldgepreßtem Lederbezuge. In der Mitte der Deckel ein mit vier Schleifen versehener Vierpaß, in dem vier aus verschlungenem Rankenornamente herzförmig gebildete Figuren im Geschmacke Flötners liegen. In einigem Abstande vom Rande ein mit Flötnerschem, arabeskenartig verschlungenem Rankenwerke verzierter Rahmen, in dessen Ecken je ein kleines Blatt liegt, während außen an dieselben je ein Viertel des mittleren Vierpasses mit der inneren Spitze tritt. … Zu Seiten des Vierpasses die Jahreszahl 1542 [sic], unten die Bezeichnung a dmxxxviii, auf der Rückseite oben .h.i.b., unten die Jahreszahl .1590. Auf den Feldern der Rücken zweimal übereinander ein Teil des Rankenornamentes aus dem Rahmen der Deckel. An den Zeiten je zwei, oben und unten je rotbraunes Verschschluβband.”); Zierlich schreiben: der Schreibmeister Johann Neudörffer d.Ä. und seine Nachfolger in Nürnberg (Munich 2007), pp.77, 116. ebdb w003205 (“Werkstattzuschreibung unsicher (Zuschreibung nach I. Schunke)”; ebdb k009830 (mistakenly gives “1588” as the date of the edition). The ebdb credits one other book to the Heußler shop (ebdb w003205), a manuscript “Nürnberger Chronik” of 1563 (Erfurt, Gotha Forschungsbibliothek, Mscr 302; ebdb k009828). It shares with the “Römer bindings” only the tool used in the outer corners.

25. London, British Library, C.69.aa.18. The copy is inscribed by the Leipzig merchant Hanns Lebzelter (1535-1588), dated 1549.

26. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Felix M. Warburg, 1928 (28.106.28). Susanne Meurer, “Translating the hand into print: Johann Neudörffer’s etched writing manual” in Renaissance Quarterly 75 (2022), pp.403-458 (p.439).

27. Zurich, Zentralbibliothek, Gall. VII bis. 74. Illustrated by Hobson, op. cit., Pl. 7. ebdb k009827.

28. A second binding attributed by the ebdb to this shop is Nuremberg, Stadtarchiv, E5/10 no.5, a manuscript “Meisterbuch des Glaserhandwerks” (ebdb k009826). It shares no tools with the “Romer bindings”.

29. Weimar, Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Fol max 29: Georg Hartmann, Compositiones horologiorum et aliorum instrumentorum. Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Die lateinischen Handschriften bis 1600 (Wiesbaden 2004), pp.35-44 (“zeitgenössischer Kalbsledereinband mit Rollenstempel, Einzelstempeln (Distel) und einer aus Filigranplattenstempeln zusammengesetzten Rosette in Golddruck (wahrscheinlich von Christoph Heusler, 1578 Vorsitzender der Buchbinderinnung in Nürnberg, vgl. die Stempel auf R.I. II. 960 [Vatikanstadt], abgebildet in Schunke …”).

the “römer binder” – bindings with römer exlibris

(1) Andrea Alciati, Clarissimi viri d. Alciati Emblematum libri duo (Lyon: Jean de Tournes & Guillaume Gazeau, 1549)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris (mid-16C), across centre fore-edge “55” in brown ink

● Christoph Wenzel Graf Von Nostitz-Rokitnitz (1643-1712), armorial exlibris, lettered “C.W.G.V.N.”

● Ader Picard Tajan & Claude Guérin, Manuscrits et livres, Paris, 21 June 1985, lot 14 (“in-16, maroquin rouge, plats ornés d’un double compartiment de deux fillets croisés aux angles, fleurons d’angles et fleuron central, tranches dorées … Relié en tête, curieux ex-libris peint sur un feuillet de vélin.)

● Lucien Scheler - bought in sale (FF 46,000) [Lardanchet]

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York [Von Arnim]

● Otto Schäfer (1912-2000), acquired in 1986 (OS 1360), circular inkstamp on lower pastedown

● Otto-Schäfer-Stiftung e.V., Schweinfurt

● Sotheby’s, The collection of Otto Schäfer. Part III: Illustrated books and historical bindings, New York, 1 November 1995, lot 5 (realised $9200) [RBH 6762-5]

● Marlborough Rare Books, London; their Catalogue 169: Varia (London 1997), item 4 (£9000; illustrated on upper cover; “It is one of a small group of books bound for the ‘German Grolier’, a member of the Römer family, patricians of Nuremberg, with their hand-painted arms, heightened with gold, on a vellum leaf inserted at the beginning of the volume. [erroneously as] The Römer-Von Nostiz-Hoe-Coolidge copy.” [confusing Von Arnim nos. 47a and 47b])

● Librairie Lardanchet, Paris

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1999) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #3085]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana, III: Art, architecture and illustrated books, London, 9 July 2024, lot 441 [link; RBH L24402-441]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($12,700)

● Librairie Lardanchet, Paris; their Livres, manuscrits, dessins & reliures (Paris [2024]), item 3 (€25,000)

literature

Manfred von Arnim, Europäische Einbandkunst aus sechs Jahrhunderten: Beispiele aus der Bibliothek Otto Schäfer (Schweinfurt 1992), no. 47a

(2) Ammianus Marcellinus, Rerum gestarum libri decem et octo (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1552)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), exlibris

● Charles-Henri-Auguste Schefer (1820-1898)

● Léon Tual & Charles Porquet, Catalogue de bons livres anciens et modernes, provenant de la bibliothèque de feu Ch. Shefer, Première partie, Paris, 8-16 May 1899, lot 468 (“Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum libri decem et octo. Lugduni apud Seb. Gryphium, 1552. In-12, mar. rouge, fil., coins et mil. dorés, tr. dor. (Rel. anc.) Armoiries peintes sur le feuillet de garde.”) [link]

● Joseph Baer & Co., Frankfurter Bücherfreund. Mitteilungen aus dem Antiquariate von Joseph Baer & Co. Hervorragende Bucheinbände des XIV. bis XX. Jahrhunderts (13 Jahrgang, 1919-1920; Neue folge Nr. II, Heft 2/3), item 972 & Pl. CV (M 2000; “Maroquin rouge, fil. dor. à compartiments, jolis fleurons au centre et aux angles; tr. dor. Jolie reliure lyonnaise d’une conservation irréprochable”) [link]; Joseph Baer & Co., Lagerkatalog 690: Bucheinbände (Frankfurt am Main 1923), item 192 & Pl. 15

literature

Anthony Hobson, “Some sixteenth-century buyers of books in Rome and elsewhere” in Humanistica Lovaniensia 34A (1985), pp.65-75 (p.74 no. 7 [erroneously as 1562])

(3) Pierre Belon, Les observations de plusieurs singularitez et choses memorables, trouvées en Grece, Asie, Judée, Egypte, Arabie et autres pays estranges (Antwerp: Christophe Plantin, 1555)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris (mid-16C)

● Ludwig Rosenthal’s Antiquariat, Bibliothek Lobris: Katalog der reichhaltigen Bibliothek des gräflichen Schlosses Lobris bei Jauer in Schlesien und anderer Sammlungen, Munich, 22 April 1895, lot 313 (illustrated; “Maroquin rouge, très-belles dorures à compart. sur les plats … Sur le feuillet de garde un curieux Exlibris du temps, le blason de la famille Römer de Nürnberg imprimé au frotton et colorié (d’or, à la tête de cygne tenant un fer à cheval.)”) [link]

(4) Bernhard Brandt, Volkumner Begriff aller lobwürdigen Geschichten und Thaten (Basel: Jacob Kündig, 1553)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris (mid-16C)

● Henry Huth (1815-1878)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the famous library of printed books, illuminated manuscripts, autograph letters and engravings collected by Henry Huth, and since maintained and augmented by his son Alfred H. Huth, Fosbury Manor, Wiltshire. The printed books and illuminated manuscripts. First portion, London, 15-24 November 1911, lot 896 (“emblazoned coat-of-arms on fly-leaf, contemporary brown morocco, with blind stamped ornaments, plain edges, well-preserved”)

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£10 5s); their Catalogue of German, Dutch & Flemish illustrated books, XV-XVI Cent., Part I: A-H (London 1914), item 146 (illustrated; £24; “contemporary brown morocco, with blind tooled arabesque ornaments … on fly-leaf are the original owner’s arms illuminated, occupying most of the page: or, an ostrich’s head sa. With horseshoe, crest the same. This is evidently painted over a woodcut base, having the shield blank. A beautiful and wonderfully preserved specimen of German binding in Italian style”); Early printed books arranged by presses, Part II (London [1918?]), item 2124 (£24) [link]

(5) Andrea Fulvio, lllustrium imagines (Rome: Giacomo Mazzocchi, 1517)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris on vellum, across centre fore-edge “15” in brown ink

● Christoph Wenzel Graf Von Nostitz-Rokitnitz (1643-1712), armorial exlibris, lettered “C.W.G.V.N.”

● Nostitz, family library (Schloss Lobris, Niederschlesien)

● Ludwig Rosenthal’s Antiquariaat, Bibliothek Lobris, Katalog der reichhaltigen Bibliothek des gräflichen Schlosses Lobris bei Jauer i/Schlesien und anderer Sammlungen, Munich, 22 April 1895, lot 1151 (“Ex-libris de Römer gravé en bois et colorié, tiré sur vélin”)

● Arthur Kay, exlibris

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of a selected portion of the extensive and valuable library the property of Arthur Kay, Esq., H.R.S.A., 11, Regent Terrace, Edinburgh, London, 26-29 May 1930, lot 397 ([offered with no. 6 in this list, Huttich] “uniformly bound in 16th century red morocco, gilt panel and centre ornament on sides … Each book has an inserted woodcut coat of arms before the title, that in the second book [Fulvio] differing from the first [Huttich] and printed on vellum. Both cuts are coloured”)

● E.P. Goldschmidt, London - bought in sale (£9; E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., Stock Books 1921-1981, #11760, £4, in Grolier Club Library [link]); their Catalogue 147: A Collection of books on a variety of subjects including early medicine and science (London 1971), item 85 (“A vellum leaf, with the fine woodcut bookplate of the Römer family of Nuremberg, finely illuminated in gold and colours, bound in before title. Bound c. 1550 (at Nuremberg?) in red morocco over thin wooden boards; both sides divided into panels by double gilt fillets, the four corner compartments filled with a fine arabesque tool which is repeated in the central compartment four times to form a large arabesque roundel … The very fine woodcut bookplate shows the arms of the Römer family of Nuremberg: the arms or, an ostrich’s head sa., holding in its beak a horseshoe arg., rising from clouds arg. This family must have had a considerable library of volumes bound in the same style as several of them - all in astonishingly fresh condition - have passed through our hands (see Cat. 143, No. 144, Messisbugo). However very few of them appear to contain the bookplate as the only record of another volume with the ex-libris we were able to trace is in Leighton’s “Catalogue of German Woodcut Books” (1914), No. 146, where a volume in an almost identical binding (reproduced) with the same bookplate is described, the only difference being that the shield of the Leighton copy was blank whereas in ours the charge of the shield is also in woodcut.”) [RBH 147-85] [Goldschmidt Stock Books, op. cit., sold 30 May 1930 to Eisemann £6 16s 6d]

● Heinrich Eisemann, London

● Wynne R.H. Jeudwine (1920-1984)

● Bloomsbury Book Auctions, Valuable collection of illustrated books and books illustrating the art of printing formed by the late W.R. Jeudwine (sold by order of the executors), London, 18 September 1984, lot 66 (illustrated; “a woodcut coat of arms of the family (Siebmacher 22, 88) on vellum and coloured by hand is bound at the beginning”)

● Pierre Berès, Paris - bought in sale (£13,200); his Catalogue 77: Livres à figures des XV and XVI siècles (Paris 1987), item 39 (FF 250,000)

● Jaime Ortiz-Patiño (1930-2013)

● Sotheby’s, The Jaime Ortiz-Patiño collection of important books and manuscripts, New York, 21 April 1998, lot 113 [RBH NY7119-113]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($22,000)

● Librairie Thomas-Scheler, Paris

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1999) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #3012]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana, III: Art, architecture and illustrated books, London, 9 July 2024, lot 527, unsold against estimate, £20,000-£30,000, link [RBH L24402-527]; reoffered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana VIII, Paris, 3-17 December 2025, lot 133, link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (€40,640) [RBH pf2525-133]

literature

Hobson, op. cit., p.74 no. 1

(6) Johann Huttich, Roemische Keyser ab contravegt vom ersten caio Julio an untz uff den jetzigen H.K. Carolum. (Strassburg: Wolfgang Köpfel, 1526)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris

● Ludwig Rosenthal’s Antiquariat, Bibliothek Lobris: Katalog der reichhaltigen Bibliothek des gräflichen Schlosses Lobris bei Jauer in Schlesien und anderer Sammlungen, Munich, 22 April 1895, lot 1099 (“Roth Lederbd. mit reicher Vergold. auf den Decken … Ex-libris der Nürnberger Familie Römer in Holzschnitt, alt colorirt”)

● Arthur Kay, exlibris

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of a selected portion of the extensive and valuable library the property of Arthur Kay, Esq., H.R.S.A., 11, Regent Terrace, Edinburgh, London, 26-29 May 1930, lot 397 [offered with no. 5 in this list, Fulvio]

● E.P. Goldschmidt, London - bought in sale (£9; E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., Stock Books 1921-1981, #11759, £5, in Grolier Club Library [link]) [Goldschmidt Stock Books, op. cit., sold 30 May 1930 to Eisemann £8 9s 6d]

● Heinrich Eisemann, London

(7) Iamblichus, Iamblichvs De Mysteriis Aegyptiorvm, Chaldæorum, Assyriorum; Proclvs in Platonicum Alcibiadem de Anima, atque Dæmone; Idem de Sacrificio & Magia; Porphyrivs de Diuinis atq[ue] Dæmonib.; Psellvs de Dæmonibus; Mercvrii Trismegisti Pimander; Eiusdem Asclepius (Lyon: Jean de Tournes, 1549)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris, across centre fore-edge “49” in brown ink

● perhaps by descent Konrad Feuerlein (1629-1704), Johann Konrad Feuerlein (1656–1718), to Jakob Wilhelm Feuerlein (1689-1766), his gift to Ernst Salomon Cyprian (1673-1745), director of the ducal library at Friedenstein Castle in Gotha (Schrader)

● Herzogliche Bibliothek, Gotha, oval black inkstamp lettered BIBLIOTHECA DVCALIS GOTHANA. 1799 (comparable image, [link])

● Erfurt, Universität, Forschungsbibliothek Gotha, Ant 8° 00020a/01 (opac vor dem Titelblatt ist Pergamentblatt mit kol. Wappen von Georg Römer eingefügt, roter Ganzledereinband mit Goldprägung, aufgeklebter Pergamentrücken [link])

citations

Benjamin Schrader, Ein Strauß in der Forschungsbibliothek: Die Buchsammlung Georg Römers, in Blog der Forschungsbibliothek Gotha (posted 5 May 2025 [link])

Deutschen Bibliotheksverbandes e.V., ProvenienzWiki - Plattform für Provenienzforschung und Provenienzerschließung (image sources: exlibris [link], upper cover [link], lower cover [link])

(8-9-10-11) Titus Livius, [Opera] (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1548) [part set of 5 volumes in sextodecimo format: Decas prima 1548; Decas tertia 1548; Decas quarta 1548; Decadis quintae libri quinque 1548; Decadum XIIII Titi Livii Patavini epitome 1548 – four volumes are recorded with Oskar Roesger by Hildebrandt, op. cit.; two were offered in the Weiser sale (1924), the other two volumes are unlocated]

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), exlibris

● Oskar Roesger, Bautzen [bookseller, b. 1843]

literature

Adolf M. Hildebrandt, “13. Sitzung des Ex-Libris-Vereins. Berlin, den 13. December 1892” in Zeitschrift für Bücherzeichen- Bibliothekskunde und Gelehrtengeschichte 3 (1893), pp.46-48 (p.46: “Die Weller’sche Buchhandlung (Oskar Roesger) in Bautzen übersendet vier in Holzschnitt gedruckte, sehr sauber kolorirte, fein mit Gold aufgelichtete Darstellungen ein und desselben Wappens in verschiedenartiger Stilisirung. Die Blättchen waren vier Bänden einer Ausgabe des Livius vom Jahre 1548 vorgebunden. Das Wappen (Römer in Nürnberg) zeigt in Gold einen aus einer schwebenden blauen Wolke wachsenden schwarzen Straussenrumpf mit einem eisenfarbenen Hufeisen im Schnabel; derselbe wächst auch aus dem Helm, dessen Decken golden und schwarz sind.”) [link]

(-) Titus Livius, Titi Livii Patavini Latinae Historiae Principis Decas prima (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1548)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), exlibris

● Oskar Roesger, Bautzen [bookseller, b. 1843]

● Ernst Weiser

● Antiquariat Emil Hirsch, Sammlung Ernst Weiser: schöne und kostbare Bucheinbände, französische Kupferwerke des XVIII. Jahrhunderts, Munich, 1 December 1924, lot 156 & Pl. 8 (“Roter Maroquinband mit hübscher Vergoldung: von 3 blindgepreßten Linien eingefaßt, ist das Feld durch 8 feine, durchgezogene Goldlinien in Rechtecke u. Quadrate eingeteilt mit sehr schönen Eck- u. Mittelornamenten, Weinlaubstempel in den Ecken des Mittelfeldes. Goldschnitt, Schließbänder. Vgl. Baer Kat. 690, Nr. 192 u. 326. Reizender französ. Einband des 16. Jahrh. Die fein gezeichneten Ornamentstempel erinnern an Holzschnittvignetten Bernard Salomons in Lyoner Drucken. - Ecken, Gelenke, Kopf u. Schwanz des Rückens geschickt ausgebessert, die Deckelverzierung selbst unberührt. Neuer Vorsatz.”) [link]

(-) Titus Livius, Titi Livii Patavini Latinae Historiae Principis Decas tertia (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1548)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), exlibris

● Oskar Roesger, Bautzen [bookseller, b. 1843]

● Ernst Weiser

● Antiquariat Emil Hirsch, Sammlung Ernst Weiser: schöne und kostbare Bucheinbände, französische Kupferwerke des XVIII. Jahrhunderts, Munich, 1 December 1924, lot 157 (“Derselbe Einband. Ebendso.”)

(12) Guillaume Rouillé, Prima [-secunda] pars promptuarii iconum insigniorum a seculo hominum, subjectis eorum vitis, per compendium ex probatissimis autoribus desumptis (Lyon: Guillaume Rouillé, 1553), bound with: Jacopo Strada, Epitome thesauri antiquitatum, hoc est, imperatorum Romanorum orientalium et occidentalium iconum (Lyon: Jean de Tournes and Thomas Guérin, 1553)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris

● Christoph Wenzel Graf Von Nostitz-Rokitnitz (1643-1712), armorial exlibris, lettered “C.W.G.V.N.”

● Ludwig Rosenthal’s Antiquariat, Bibliothek Lobris, Katalog der reichhaltigen Bibliothek des gräflichen Schlosses Lobris bei Jauer i/Schlesien und anderer Sammlungen, Munich, 22 April 1895, lot 1164 (binding illustrated; “Sur le feuillet de garde se trouve un superbe et très-grand ex-libris du temps, les armes de la famille Römer de Nüremberg, impr. au frotton et color. à la main, richement rehausse d’or. Ex-libris échappé à Warnecke”)

● Robert Hoe (1839-1909)

● Anderson Galleries, Catalogue of the library of Robert Hoe, Part I: L to Z, New York, 1-5 May 1911, lot 2666

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($60)

● Thomas Jefferson Coolidge, Jr. (1863-1912)

● Marlborough Rare Books, London (Von Arnim)

● Otto Schäfer (1912-2000), acquired in 1986 (OS 1328)

● Otto-Schäfer-Stiftung e.V., Schweinfurt

● Sotheby’s, The collection of Otto Schäfer. Part III: Illustrated books and historical bindings, New York, 1 November 1995, lot 186

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased in the above sale via Martin Breslauer, Inc.) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #3115]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 78 [link; RBH 11245-78]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($19,050)

literature

Carolyn Shipman, A catalogue of books printed in foreign languages before the year 1600, forming a portion of the library of Robert Hoe (New York 1907), II, p.134 (q.v. Promptuarium; “on a fly leaf are painted arms in colours”)

Hobson, op. cit., p.74 no. 5 & Pl. 6

Von Arnim, op. cit., no. 47b

(13) Franciscus Tarapha, De origine, ac rebus gestis regum Hispaniae liber, multarum rerum cognitione refertus (Antwerp: Joannes Steelsius, 1553)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris

● New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, 075769 (opac 16th-century Nuremberg gilt morocco, with arms of Römer family on fly leaf [link])

literature

Hobson, op. cit., p.74 no. 4

Pierpont Morgan Library, Nineteenth Report to the Fellows (New York, 1981), p.106 & Pl. 18 (“light brown morocco gilt, with an arabesque tool disposed in centre- and cornerpiece style; bound for a member of the Römer family)

(14) Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’più eccellenti architetti, pittori et scultori italiani (Florence: Lorenzo Torrentino, 1550)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris

● Amadeus Svajer (1727-1791), armorial exlibris

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 670 (“3 parts in 2 vol., bound in 1 … thick paper … fine contemporary Roman binding … The same tool used for the cornerpieces and centrepiece is found on a binding which belonged to Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga (De Marinis, I, pl. 110, no. 918) and on a Papal register of 1535 (De Marinis, I, pl. 114, no. 638)”)

● “Dr Fergusson” - bought in sale (£550)

● Sotheby’s, Catalogue of Italian printed books with sections on political economy and science. The second and final portion, London 12-13 May 1975, lot 922 (illustrated; “coat-of-arms of the original (German) owner painted on flyleaf and heightened with gold, in a fine contemporary Roman binding of red morocco gilt, gilt border, leaves at inner corners, an openwork tool at each outer corner repeated four times to make a centrepiece, four ties lacking, in a cloth case, with armorial bookplate of Amadeus Svajer from the J. R. Abbey collection”)

● “Evans” - bought in sale (£4800) [RBH PERPETUA-922]

literature

Hobson, op. cit., p.74 no. 3

the “römer binder” – bindings without römer exlibris

(15) Leon Battista Alberti, L’architettura di Leonbatista Alberti tradotta in lingua fiorentina da Cosimo Bartoli (Florence: Lorenzo Torrentino, 1550)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg) (?)

● Sir Andrew Fountaine (1676-1753), added crest on spine

● “Manuscript inventory of the collection of Sir Andrew Fountaine at Narford, Norfolk”, post-mortem inventory taken by Captain William Price, 1753 [London, National Art Library, transcription by Candace Briggs & Laurie Lindey, “A Catalogue of the Library together with the Manuscripts &c at Narford”, p.36: “Class Tenth … Folio … L’Architectura di Leon. Batt: Alberti Ferenz 1550”, listing books by bookcase and shelf number]

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a selection of valuable books & manuscripts from the library of Sir Andrew Fountaine, of Narford Hall, Norfolk, collected by him in the reigns of Queen Anne and Kings George I and II, London, 11-14 June 1902, lot 8 (“contemporary Italian red morocco, ornamented gilt back, arabesque frame sides with centre ornaments, g.e. fine copy”)

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£2 12s)

● Joseph Baer & Co., Lagerkatalog 690: Bucheinbände (Frankfurt am Main 1923), item 326 & Pl.48 (“richement doré à 6 compartiments, dont cinq renferment un éléphant entouré de petits fers … Notre reliure provient probablement de l’atelier de reliure de Pierre Regnault … mais on peut aussi penser à Madeleine Boursette, veuve et successeur de François Regnault; car on trouve également l’éléphant sur les reliures qui sortaient de ces mains (Voir Gruel, Manuel II p.39).”)

● Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Rosenwald Collection, NA2517 .A34 1550 [link]

literature

A Catalog of the Gifts of Lessing J. Rosenwald to the Library of Congress (Washington, DC 1977), no. 847 (“Provenance: Sir Andrew Fountaine with his emblem, an elephant, on the back of the red morocco binding.” [link])

Hobson, op. cit., p.74 no. 2

(16) Paolo Giovio, Libro de la vida y chronica de Gonçalo Hernandes de Cordoba, llamado por sobrenombre el gran capitan (Antwerp: Gerard Speelmans, 1555)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg) (?)

● Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale Albert I, LP 5.657 A [opac, link]

literature

Hobson, op. cit., p.74 no. 6

(17) Francisco Lopez de Gómara, Historia de Mexico con el descubrimiento dela nuena España (Antwerp: Joannes Steelsius, 1554)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg) (?)

● Libreria Ulrico Hoepli & E. Aeschlimann, Autographes, miniatures, manuscrits, incunables, livres illustrés du XVIe au XIXe siècle, éditions de luxe, livres d’art, reliures, Zurich, 11-12 June 1929, lot 67 & Pl. 35 (“reliure italienne de l’époque, en maroquin rouge, avec d’élégantes impressions en or sur les plats; réglage de doubles filets, au centre une belle rosace et de jolis motifs dans les angles; dos entièrement couvert d’impressions à froid”)

(18) Cristoforo Messi Sbughi, Libro novo nel qual s’insegna a far d’ogni sorte di vivanda secondo la diversità de’ tempi (Venice: Giovanni Dalla Chiesa, 1552)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg) (?)

● Maggs Bros, London; their Catalogue 913: Music: a catalogue of manuscripts & printed books, Part one: Late medieval to second half eighteenth century (London 1968), item 137 (£140; “Contemporary Venetian brown morocco panelled sides, with gilt arabesque centre- and corner-pieces. (Slight wormholes on front cover.)”) [RBH 913-137]

● E.P. Goldschmidt, London [acquired from Maggs, 5 November 1968, £31 10s; E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., Stock Books 1921-1981, #39825, in Grolier Club Library [link]); their Catalogue 143: Books for Scholars and Collectors (London 1970), item 144 (“Contemporary brown morocco; panelled sides and arabesque centre and corner pieces in gilt”) [RBH 143-144] [Goldschmidt Stock Books, op. cit., transferred to stockbook of E.P. Goldschmidt, Inc., and eventual sale unrecorded]

(19) Onofrio Panvinio, Fasti et triumphi Rom. a Romulo rege vsque ad Carolum V Cæs. Aug. siue epitome regum, consulum, dictatorum, magistror. equitum, tribunorum militum consulari potestate, censorum, impp. & aliorum magistratuum Roman. cum Orientalium tum Occidentalium (Venice: Jacopo Strada, 1557)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg) (?)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, R.I.II.960 [opac, link]

literature

Ilse Schunke, Die Einbände der Palatina in der Vatikanischen Bibliothek (Città del Vaticano 1962), I, pp.132-133 (line drawing of upper cover)

bindings by the römer binder for other collectors

(20) Bible. NT. Syriac, Liber Sacrosancti Evangelii de Iesv Christo Domino & Deo nostro, edited by Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter and Moses Mardenus (Vienna: Michael Zimmermann, 1555)

provenance

● Johann Conrad Feuerlein, engraved exlibris

● Zurich, Zentralbibliothek, Gall. VII bis. 74

literature

Hobson, op. cit., p.75 & Pl. 7

(21) Georg Hartmann, Manuscript: Compositiones horologiorum et aliorum instrumentorum, ca 1527

No. 20 : Hartmann Ms [link]

provenance

● Weimar, Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Fol max 29

literature

Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Die lateinischen Handschriften bis 1600 (Wiesbaden 2004), pp.35-44 (“wahrscheinlich von Christoph Heusler, 1578 Vorsitzender der Buchbinderinnung in Nürnberg, vgl. die Stempel auf R.I. II. 960 [Vatikanstadt], abgebildet in Schunke …”)

(22) Johannes Neudörffer, Ein gute ordnung, und kurtze unterricht, der fuernemsten grunde aus denen die jungen, zierlichs schreybens begirlich, mit besonderer kunst und behendigkeyt unterricht und geuebt moegen werden ([Nuremberg] 1538-ca 1543)

provenance

● Hanns Lebzelter, inscription (in red ink) “Hannsen Lebzelters Kunstbuch Anno. 1549.“ (Reed, image)

● Louise Wolf, typographical exlibris

● British Museum, oval British Museum stamp “2 Ju [18]70”

● London, British Library, C.69.aa.18

literature

British Library, Database of Bookbindings [image, link]

Susan Reed, “‘The Father of German Calligraphy’: Johann Neudörffer”, British Library, European Studies blog, 13 June 2019 [link]

(23) Johannes Neudörffer, Ein gute ordnung, und kurtze unterricht, der fuernemsten grunde aus denen die jungen, zierlichs schreybens begirlich, mit besonderer kunst und behendigkeyt unterricht und geuebt moegen werden ([Nuremberg] 1538-ca 1543)

provenance

● unidentified owner, supralibros, upper cover is lettered “S W G D M D | V I N I N E | 1549” and the lower cover “H I B | 1590”

● Nuremberg, Bibliothek des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, Postinc. 8° W.954 (formerly Nr. 7594) [opac, link]

literature

Katalog der im germanischen Museum vorhanden interessanten Bucheinbände (Nuremberg 1889), p.70 no. 280 (“Pappband mit braunem, goldgepreßtem Lederbezuge. In der Mitte der Deckel ein mit vier Schleifen versehener Vierpaß, in dem vier aus verschlungenem Rankenornamente herzförmig gebildete Figuren im Geschmacke Flötners liegen. In einigem Abstande vom Rande ein mit Flötnerschem, arabeskenartig verschlungenem Rankenwerke verzierter Rahmen, in dessen Ecken je ein kleines Blatt liegt, während außen an dieselben je ein Viertel des mittleren Vierpasses mit der inneren Spitze tritt. … Zu Seiten des Vierpasses die Jahreszahl 1542 [sic], unten die Bezeichnung A DMXXXVIII, auf der Rückseite oben .H.I.B., unten die Jahreszahl .1590. Auf den Feldern der Rücken zweimal übereinander ein Teil des Rankenornamentes aus dem Rahmen der Deckel. An den Zeiten je zwei, oben und unten je rotbraunes Verschschluβband.”)

Zierlich schreiben: der Schreibmeister Johann Neudörffer d.Ä. und seine Nachfolger in Nürnberg (Munich 2007), pp.77, 116

(24) Johannes Neudörffer, Ein gute ordnung, und kurtze unterricht, der fuernemsten grunde aus denen die jungen, zierlichs schreybens begirlich, mit besonderer kunst und behendigkeyt unterricht und geuebt moegen werden ([Nuremberg] 1538-ca 1543)

provenance

● New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Felix M. Warburg, 1928 (28.106.28)

literature

Susanne Meurer, “Translating the hand into print: Johann Neudörffer’s etched writing manual” in Renaissance Quarterly 75 (2022), pp.403-458 (p.439)

possible additions to römer bindings census

(25) Francesco Petrarca, Le rime del Petrarcha tanto piu corrette, quanto piu ultime di tutte stampate (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1549)

provenance

● Marchese Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, exlibris

● Milan Biblioteca Trivulziana, Petr.74

literature

Marisa Gazzotti, in Il Fondo Petrarchesco della Biblioteca Trivulziana: Manoscritti ed edizioni a stampa (sec. XIV-XX), edited by Giancarlo Petrella (Milan 2006), pp.149-150 no. 27 (“Bella legatura del sec. XVI in marocchino rosso, su cartone, di area tedesca. Una cornice di doppio filetto inciso a secco inquadra cornici e impressioni dorate a ferri negli angoli e al centro dei piatti; gli scomparti del dorso sono delimitati da filetti a secco. Sul risguardo incollato al piatto anteriore ex libris di Gian Giacomo Trivulzio; stato di conservazione buono.”)

British Library, Database of Bookbindings, link

(26) Pedro Covarrubias, Rimedio de’ giuocatori (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1561), bound with: Bartolomeo Taegio, L’humore dialogo (Milan: Giovanni Antonio degli Antoni for Valerio & Girolamo Meda, 1564)

provenance

● Römer, family library (Nuremberg), painted exlibris (mid-16C)

● unidentified owner, inscription “Leonardo di Filicaia” (17C) [Breslauer, as Filicara]

● Georges Vicaire, exlibris (Breslauer)

● Federico Gentili Di Giuseppe (1868-1940)

● Adriana Raphaël (née Gentili di Giuseppe) Salem (1903-1976), pink circular exlibris “a.r.s.”

● Houghton Library, Harvard University [Gentili di Giuseppe collection of “over a thousand volumes” deposited ca 1939-1945 by Adriana Salem; James E. Walsh, “Forming Harvard’s collection of incunabula” in Harvard Library Bulletin 8 (1997), pp.1-74 (pp.42-43)]

● Ward M. Canaday (1902-1991) (?) [apparently purchased the Gentili di Giuseppe collection from Adriana Salem, in 1955, and “gradually transferred ownership to Harvard over the next ten years” (Walsh)]

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York; their Catalogue 110: Fine books and manuscripts in fine bindings from the fifteenth to the present century: followed by literature on bookbindings (New York 1992), item 50 ($4500)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1992) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2318]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part VII, London, 11 July 2025, lot 1639 (£5080) [link]