Luis de Torres (1495-1553)

In 1998, T. Kimball Brooker studied a group of seven gold tooled Roman bindings, of which five were in the Bibliotheca Brookeriana.1 All are Greek and Latin classical texts (six are Aldine press editions), printed between 1503 and 1538, bound in brown or black goatskin with the initials L.T. on their covers. The quality of the bindings suggested to him a wealthy patron. The presence on each binding of a gold-tooled title running down the spine suggested a collector within a small circle in Rome that had adopted the modern method of book storage, of standing books upright on shelves, side by side, with their spines outward. From this he surmised that L.T. had probably amassed a large library.

In one of the books, a copy of the 1503 Aldine Euripides (no. 2 in List below), a partially-deleted inscription at the head of its title-page reads “[name cut away] D. Ludovicus de Torres hoc munere [a few words obliterated] Ann. MDLXX Cal. Sept.”, indicating that one Luis de Torres had presented the volume in September 1570 to a person whose name was subsequently excised. The entire inscription has been crossed out, except “Ann. MDLXX”, which has been extended to “Ann. MDLXXXIIII” by the hand responsible for the obliteration.2 After investigating the De Torres family, T. Kimball Brooker concluded that “L.T.” on the cover was Luis de Torres (1495-13 August 1553), and the “Ludovicus de Torres” who gave the book away was his nephew, Luis II de Torres (1533-1584). The identity of the recipient remains a mystery.

Inscription of Luis II de Torres (1533-1584), presenting his uncle’s 1503 Euripides to a person whose name was subsequently excised

Luis de Torres (1495-13 August 1553) was the fifth son of an Andalusian Jewish convert, Fernando de Córdoba (d. 1523), who had participated in the reconquest of the city of Málaga from the Muslims in 1487, and afterwards established lucrative businesses in the port.3 Fernando married first Dona Inés Fernández, by whom he had six children, all given the surname Torres. Nothing is known of Luis’s education. At an uncertain date, Luis travelled to Rome, where he came under the protection of the lawyer Gonzalo Fernández de Ávila, Canónigo and Chantre of the cathedral of Málaga, nephew and heir of Pedro Díaz de Toledo, bishop of Málaga (1487-1499).4 A converted Jew, Gonzalo had fled from Málaga to Rome under inquisitorial pressure, arriving there in 1507. By 1518, he had been adopted by Cardinal Raffaele Sansoni Riario (1461-1521), bishop of Málaga.

Through Gonzalo’s influence, Luis obtained in 1518 an office in the apostolic chancery (scriptor brevium, held until 1538); in 1527, he was appointed secretarius (held until 1542).5 When Gonzalo died, in 1527, Luis was named in his testament as universal heir,6 thereby adding the valuable Díaz de Toledo properties in the bishopric of Málaga to his already substantial fortune. Luis afterwards formed a new attachment to Cesare Riario, Bishop of Málaga (1518-1540), administering assets and resolving lawsuits with the Cabildo of Málaga.7 He acquired two additional offices in the papal chancery, those of scriptor cancellarie in 1529 (held until 1542) and magister registri cancellarie in 1537 (held until 1550). In 1541, Luis was involved in lawsuits relating to the tithes of the collegial church of Antequera, and in 1543-1546 in disputes between the Conde de Ureña and Cabildo of Málaga over tithes of Archidona, Olvera and Montejícar. Luis had begun in 1542 to acquire properties on the south side of the Piazza Navona, and about 1550 he commissioned the architect Pirro Ligorio to design a new palace incorporating the older structures. In 1548, on the resignation of Cardinal Niccolò Ridolfi, Pope Paul III appointed Luis as Archbishop of Salerno, permitting him to take possession “litteris non expeditis”.

Luis died in Rome on 13 August 1553, aged 58. He was interred provisionally in the twelfth-century Roman church of S. Maria Dominae Rosae, then in the newly-built funerary chapel of the De Torres family in S. Caterina de’ Funari, and finally (according to his testamentary wishes) in the family chapel in Málaga cathedral.8

The Archbishop’s nephew, Luis II de Torres (1533-1584), who in 1570 gave away the 1503 Aldine Euripides, was the son of Juan de Torres and Catalina de la Vega. He was born in Málaga and educated in the grammar school of Juan de Valencia, arrived in Rome around 1550, and with the help of his uncle was quickly appointed notarius prothonotariorum and subsequently clericus camera.9 In 1570, Luis II was sent as a papal nuncio to the Spanish and Portuguese courts, to discuss the league against the Turks. He arrived in Madrid on 15 April, travelling thereafter between Córdoba, Seville, and Sintra, with an excursion to Málaga, where he assisted in the establishment of the Jesuit Colegio de San Sebastián, visited his parents, and Juan de Valencia, to whom he gave some 500 ancient Roman coins.10 It could be that the partially-deleted inscription in the Euripides dated September 1570 names a travel companion, or someone Luis met during this journey.11

In December 1573, at the request of Philip II of Spain, Luis II was consecrated Archbishop of Monreale in Sicily, and he immediately installed his nephew and namesake, Luis III (son of his brother Fernando), as vicar general. Luis III was subsequently ordained, succeeded his uncle as Archbishop of Monreale, and in 1606 was raised by Pope Paul V to Cardinal-Priest. Unlike his uncle, who visited his diocese rarely, Luis III became strongly attached to Monreale, endowing the library of the newly-founded Seminario Arcivescovile in 1594 with some 3000 books from the De Torres family library, and publishing in 1596 a history of the diocese.

The books in Luis III’s gift to the seminary of Monreale typically have at the top of their title-page an ownership inscription in the form “L. Archiep.o Monr.le”, “L. Archiepisc. Montisregal.”, or “Don. L. De Torres”, and at the foot an 18th or 19th century seminary pressmark in forms similar to “XXII E 26” and “Arm. XIV B. 4”.12 None of the seven volumes in L.T. bindings has such an inscription (but see entry below no. 2, Euripides), or any other evidence of Luis III’s ownership or that of the Seminario Arcivescovile.13 It may be that the L.T. bindings had become separated from the De Torres family library at an early date.

The seven bindings were executed by three different Roman shops between the mid-1530s and early 1540s. Four volumes (nos. 2, 5-7 in the census below) are structurally similar and are decorated using the same kit of tools and handle-letters. This shop also bound for an unidentified owner who used an impresa with the Horatian motto “Si fractus illabatur orbis”.14 Two volumes (nos. 3-4) were bound in a shop that also worked for a collector whose books feature the initials F.T. on their cover. One binding (no. 1) is from a shop which worked for a collector whose initials are G.A.C. and possibly also for Cardinal Giovanni Salviati (1490-1553).

1. T. Kimball Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part I” in The Book Collector 47 (1998), pp.508-518; T. Kimball Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part II” in The Book Collector 48 (1999), pp.32-53. See also T. Kimball Brooker, Upright works: the emergence of the vertical library in the sixteenth century, Thesis (Ph.D.), University of Chicago, 1996, pp.811-814 (“Exhibit 6: Roman bindings with spine titles (1530s). Luis de Torres”).

2. The page is illustrated by Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part II”, op. cit., p.52 Fig. 6a.

3. On the Jewish origin of the De Torres family, see María Teresa López Beltrán, “Los Torres de Málaga: Un ilustre linaje de ascendencia judía con proyección internacional” in Creación artística y mecenazgo en el desarrollo cultural del Mediterráneo en la Edad Moderna (Málaga 2011), pp.47-63 [link, link]; Antonio Rodríguez Linares, “Patrimonio, integración y ascenso social: la familia judeoconversa de los Torres. Entre Málaga e Italia” in Historia y Genealogía: Revista de estudios históricos y genealógicos 10 (2020), pp.212-253 [link].

4. Several profiles of Luis de Torres give 1520 as the date of his arrival in Rome, however Luis seems to have become a curial officer in 1518. Cf. María Teresa López Beltrán, “El poder económico en Málaga: la familia Córdoba-Torres (1493-1538)” in Las ciudades andaluzas (siglos XIII-XVI). Actas del VI Coloquio Internacional de Historia Medieval de Andalucía (Málaga 1991), pp.463-482 (p.467 note 29).

5. For these appointments, see Thomas Frenz, Die Kanzlei der Päpste der Hochrenaissance (1471-1527) (Tübingen 1986), p.401 no. 1555; Repertorium Officiorum Romanae Curiae (rorc) database (q.v. Ludovicus de Torres) [link]. Cf. Registra brevium, March 1523 (Archivio Apostolico Vaticano, Brevia Lateranensia 8 [March 1521-September 1523], f. 352r: Regestrum brevium apostolicorum de mense Martii MDXXIII per me Ludovicum de Torres eorundem brevium scriptorem scriptum (Frenz, ibid., p.177). Several profiles of Luis de Torres give 1524 as the date of these appointments. Cf. Rosario Camacho Martínez, “Beneficencia y mecenazgo entre Italia y Málaga: los Torres, arzobispos de Salerno y Monreale” in Creación artística y mecenazgo, op. cit., pp.17-46 (p.21). Luis cannot be traced in the Roman “census” of 1527, unless he should be either the “Aloysius hispanus” or “Aloisius hispanus” dwelling in regio Sancti Angeli (the Jewish quarter) in households of 6 and 9 bocche respectively (Egmont Lee, Habitatores in urbe: The population of Renaissance Rome, Rome 2006, nos. 8025 and 8108).

6. Jesús Suberbiola Martínez, “El testamento de Pedro de Toledo, obispo de Málaga (1487-1499) y la declaración de su albacea, fray Hernando de Talavera, arzobispo de Granada (1493-1507)” in Baetica 28 (2006), pp.373-394 (p.379). [link]

7. Jesús Suberbiola Martínez, “Los Torres: una saga de altos eclesiásticos” in Creación artística y mecenazgo, op. cit., pp.167-186 (pp.170-174).

8. Rosario Camacho Martínez & Aurora Miró Domínguez, “Importaciones italianas en España en el siglo XVI: el sepulcro de D. Luis de Torres, arzobispo de Salerno, en la Catedral de Málaga” in Boletín de Arte 6 (1985), pp. 93-112; Rosario Camacho Martínez & Aurora Miró Domínguez, “Relaciones entre Málaga y Roma a través de la familia Torres. Iglesia, diplomacia y promoción artística” in Revista Eviterna 10 (2021), pp.38-54 (pp.41-43) [link]; Rosario Camacho Martínez, “Entre Italia y España: los tres enterramientos de D. Luis de Torres, arzobispo de Salerno” in La Festa delle arti. Scritti in onore di Marcello Fagiolo per cinquant’anni di studi (Rome 2014), I, pp.272-277.

9. Bruno Katterbach, Referendarii utriusque signaturae a Martino V ad Clementem IX et praelati signaturae supplicationum a Martino V ad Leonem XIII (Vatican City 1931), p.137 no. 112.

10. Francisco J. Talavera Esteso, Juan de Valencia y sus Scholia in Andreae Alciati Emblemata: introducción, edición crítica, traducción española, notas e índices (Màlaga 2001), pp.18, 373.

11. Some details of his itinerary are provided by Wenceslao Soto Artuñedo, “La familia malagueña ‘de Torres’ y la iglesia” in Isla de Arriarán: Revista cultural y científica 19 (2002), pp.163-192 (pp.169-172). Luis II’s correspondence suggests that he was in Madrid and Sintra during the month of September 1570; see the letters published in La Lega di Lepanto nel carteggio diplomatico inedito di Don Luys de Torres, nunzio straordinario di S. Pio V a Filippo II, edited by Alfonso Dragonetti de Torres (Turin 1931), pp.215-220; and unpublished letters, recently digitised, in Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Urb.lat.841. ff. 222v, 248v. [link]

12. A group of 68 books inscribed “L. Archiepisc. Montisregal.” (or similar), printed 1509-1596, and bound in wrappers or in limp boards (or modern boards), was offered by Hesketh & Ward, Catalogue 21 (London [1197?]), items 1-68 (five title-pages with inscription “L. Archiepisc. Montisregal.” reproduced).

13. The 1503 Euripides is inscribed at the foot of the title-page in an 18th-century hand “Coll. Mont. Reg. Societ. Jes. Ins. Cat.” (Collegii Montis Regalis Societatis Iesu Inscriptus Catalogo). The seminary established by Luis III at Monreale was not a Jesuit College, however one was was founded in Monreale in 1553 (suppressed in 1767, link). The inscription in the 1503 Euripides could signify that it belonged to the Jesuit College of Mondovì, in Piedmont. Ownership inscriptions styled “Coll. Mont. Reg. Societ. Jes. Ins. Cat.” are widely recorded, as for example by the Material Evidence in Incunabula (mei) database, locating volume 5 of the 1495-1498 Aldine Aristotle in the Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense (AO.XIII 9), with inscription “Collegij Montis Regalis Soc. Iesu ins. cat.” (interpreted by mei as “Mondovì, Gesuiti, Collegio, S.J.,”); volume 2 of the same set with the same inscription is in the Burndy Library, Smithsonian Institution (PA3890 .A2 1495). Both volumes have also an inkstamp “Domus Congr. Missionis Monregal” (interpreted by mei as “Mondovì, Congregazione della Missione”). That might be the deleted inkstamp in the Euripides. [link, link]

14. Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), p.xxxvi; Anthony Hobson, “Some sixteenth-century buyers of books in Rome and elsewhere” in Humanistica Lovaniensia: Journal of Neo-Latin Studies 34a (1985), pp.65-75 (pp.69-71).

books with supralibros l.t.

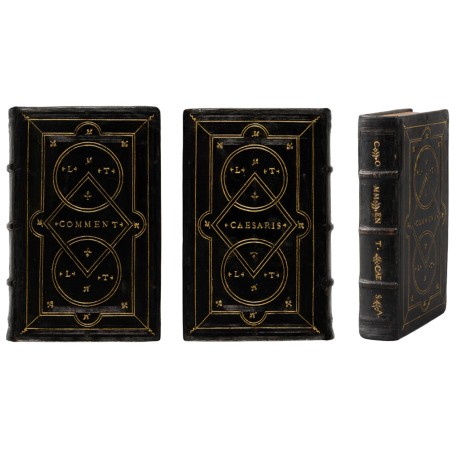

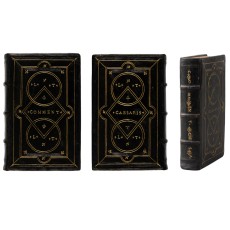

(1) Gaius Julius Caesar, Hoc volumine continentur haec. Commentariorum de bello Gallico libri VIII. De bello ciuili Pompeiano libri IIII. De bello Alexandrino liber I (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, November 1519 (sig. kk8v: mense Ianuario. M. D. XVIII)

provenance

● “No. 45”, Roman bookseller’s mark (?) beneath device on title-page

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), supralibros, initials “L.T.” on both covers

● Bodleian Library, Oxford, inkstamp on title-page, inscription “Bought at Bodleian sale of duplicates, Sotheby’s, 1865” on upper pastedown [but not traced in Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a valuable collection of curious, rare & interesting books, being purchase-duplicates from the Bodleian Library, London, 12 April 1865, nor in 3 August 1870 sale]

● Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919), exlibris on pastedown

● Christie Manson & Woods, Catalogue of the second portion of the library of C. Fairfax Murray, Esq., London, 18 March 1918, lot 136 (“original Aldine binding of dark morocco, gold lines, and title in gold on sides, gold gauffred edges”)

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£10), collation note dated 22 March 1918

● Charles Stephen Ascherson (1877-1945), exlibris

● Bernard Quaritch, London [Ascherson’s collection was sold to Bernard Quaritch in 1944/1945; cf note in The Helmut N. Friedlaender Library, Christie’s, 23 April 2001, lot 41]

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969), exlibris, acquired 21 January 1946 (JA 2712)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 171 (“Contemporary Roman (?) black morocco, panelled in gilt and blind, decorated with small leaves and with a lozenge interlaced with two circles, the title in the centre of the covers, the (owner’s) initials L.T. repeated twice on each cover, edges gilt and gauffered … Bodleian duplicate with stamp at foot of title (sale in our rooms, 12 April 1865 [no lot number]), the Fairfax Murray (sale 18 March 1918, lot 136) - C.S. Ascherson copy”)

● Alan G. Thomas, London - bought in sale (£100)

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982), exlibris

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York; their Catalogue 104/II: Fine books in fine bindings from the fourteenth to the present century (New York 1981), item 140

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1982) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0274]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library: The Aldine Collection, A-C, New York, 12 October 2024, lot 225 [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($48,260) [RBH N11294-225]

literature

Charles Fairfax Murray, Catalogo dei libri posseduti da Charles Fairfax Murray. Parte prima (London [i.e. Rome] 1899), no. 369 (“legat. orig. mar. bruno, piatti ornati”)

Charles Fairfax Murray, A list of printed books in the library of Charles Fairfax Murray ([London?] 1907), p.40 (“orig. black morocco”)

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 8

Tammaro De Marinis, Die italienischen Renaissance-Einbände der Bibliothek Fürstenberg (Hamburg 1966), pp.48-49

T. Kimball Brooker, Upright works: the emergence of the vertical library in the sixteenth century, Thesis (Ph.D.), University of Chicago, 1996, 811-814 (“Exhibit 6: Roman bindings with spine titles (1530s). Luis de Torres”, p.812 & Fig.78)

T. Kimball Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part I” in The Book Collector 47 (1998), pp.508-518 (p.508 no. 2 & Fig. 1)

(2) Euripides, Euripidou Tragodiai heptaideka on eniai met’exegeseon eisi de autai … Euripidis Tragoediae septendecim, ex quib. quaedam habent commentaria, et sunt hae. Hecuba Orestes Phoenissae Medea Hippolytys Alcestis Andromache Supplices Iphigenia in Aulide Iphigenia in Tauris Rhesus Troades Bacchae Cyclops Heraclidae Helena Ion [Greek] (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, February 1503)

provenance

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), supralibros, initials “L.T.” on lower cover

● Luis II de Torres (1533-1584), his inscription to an unknown recipient [“The inscription reads ‘[name of recipient cut away] D. Ludovicus de Torres hoc munere [one or two words obliterated] Ann. MDLXX Cal. Sept.’ and shows that Luis II de Torres presented the volume in 1570 to a person whose name was subsequently obliterated.” - T. Kimball Brooker, “Who was L.T. Part I”, op. cit., p.513]

● “Coll. Mont. Reg. Societ. Jes. Ins. Cat.,” inscription (17-18C) of a Jesuit College, at Monreale, interpreted formerly (Sotheby’s 1989) as Monreale, Sicily (however, the seminary established by Luis III at Monreale was not a Jesuit College), perhaps the Seminario della Congregazione della Missione, at Mondovì (marked their books with a circular inkstamp, here cut away)

● unidentified owner, inscription “A. Cardes (?)”

● John Alfred Spranger (1889-1968)

● Sotheby’s, Continental manuscripts and printed books, science and medicine, London, 21 November 1989, lot 22 (“library stamp excised from foot of title and repaired with slight loss of text on verso, ownership inscription deleted, Roman olive morocco gilt of c. 1535, border, small fleurons at corners, Euripides stamped on upper cover within a central sunburst, initials L T within a similar sunburst on lower cover, spine gilt in 4 compartments with Euripides lettered down the spine, spine slightly damaged at head, edges gilt and gauffered, lacking 2 pairs of ties, cloth box, ownership inscription of the Jesuit College of Monreale, Sicily”) [RBH CARLOS-22]

● “Jackson” (nom de vente of Carlo Alberto Chiesa, Milan) - bought in sale (£26,400)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1992) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0106]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library: The Aldine Collection, D-M, New York, 18 October 2024, lot 710 [link] [RBH N11499-710]

● New York, Morgan Library & Museum, PML 199249 (opac, [link])

literature

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.811 & Figs. 75a, 76a

Brooker, “Who was L.T. Part I”, op. cit., p.508 no. 3 & Figs. 2a, 3a

Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part II”, op. cit., pp.44-45 & Fig. 6a (title)

(3) Titus Lucretius Carus, Lucretius (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, January 1515)

provenance

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), supralibros, initials “L.T.” on lower cover

● unidentified owner, inscription “J.X.A. Bibl. P. Clius” (?) on title-page (17C)

● Laurence Witten, Southport

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1981) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0202]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library: The Aldine Collection, D-M, New York, 18 October 2024, lot 875 [link] [RBH N11499-875]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.812 & Fig. 77a

Brooker, “Who was L.T. Part I”, op. cit., p.509 no. 4 & Fig. 4a

(4) Pindar, Pindarou Olympia, Pythia, Nemea, Isthmia (Venice: Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, January 1513)

Image courtesy of Federico Macchi

provenance

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), supralibros, initials “L.T.” on lower cover

● Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, S.Q. L.X.22

literature

Tammaro de Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 540 (“Marr. bruno; cornice dorata di fogliami, col titolo PIN / DAR /VS; nel secondo piatto un tondo racchiude le iniziale L.T. Sul dorso, le cui estremità sono decorate con fiamme dorate, è impresso in oro il titolo PINDARVS. Taglio inciso.”)

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.811 (“not seen”)

Brooker, “Who was L.T. Part I”, op. cit., p.509 no. 5

(5) Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, M. Fabii Quintiliani Institutionum oratoriarum libri XII. Eiusdem Declamationum liber (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1538)

provenance

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), supralibros, initials “L.T.” on lower cover

● unidentified owner, inscription “Bernardino Mancini, Perugia” on endleaf (17-18C)

● Guido Vianini Tolomei (d. 1994)

● Fiammetta Soave, Rome

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1995) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2099]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Magnificent Books and Bindings, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 77, unsold against estimate $15,000-$20,000, link; reoffered by Sotheby's, Bibliotheca Brookeriana VIII, Paris, 3-17 December 2025, lot 258, link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (€10,160) [RBH pf2525-258]

literature

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.814 & Fig. 77b

Brooker, “Who was L.T. Part I”, op. cit., p.509 no. 6 & Fig. 4b

(6) Tiberius Catius Asconius Silius Italicus, Silii Italici De bello Punico secundo XVII libri nuper diligentissime castigati (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, July 1523)

provenance

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), supralibros, initials “L.T.” on lower cover

● Robert D’Arcy Hildyard, 4th Bt (1743-1814), exlibris

● Thomas Blackborne Thoroton Hildyard (1821-1888) [the former’s heir, who took the name Hildyard]

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a portion of the library of T.B.T. Hildyard, Esq. of Flintham Hall, Newark, London, 18 June 1889, lot 75 (“old Venetian binding, gold tooling, lettered in gold within a ring on obverse of cover, Silius Italicus, and on reverse L.T., gilt gaufré edges”)

● Bennett - bought in sale (£1 18s)

● Hesketh & Ward, London; their Catalogue 6 (London [1989?]), item 123 (£3000; “initials L.T. within the same roundel on back cover”)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1990 [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0333]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection: N-Z, New York, 25 June 2025, lot 1426 [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($8890) [RBH N11571-1426]

literature

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.813 & Figs 75b, 76b

Brooker, “Who was L.T. Part I”, op. cit., p.509 no. 7 & Figs. 2b, 3b

(7) Scriptores de re rustica, Libri de re rustica. M. Catonis lib. I M. Terentij Varronis lib. III L. Iunij Moderati Columellae lib. XII Eiusdem de arboribus liber separatus ab alijs. Palladij lib. XIIII De duobus dierum generibus: simulque de umbris, et horis, quae apud Palladium (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, December 1533)

provenance

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), supralibros, initials “L.T.” on lower cover

● unidentified owner, consignor to SWH sale 27 June-1 July 1898 of lots 937-1093 (“A Collection of valuable books sold in consequence of the death of the owner”)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable & rare books and important illuminated and other manuscripts, including a portion of the library of H. Sidney, Esq. and selections from other libraries, London, 27 June-1 July 1898, lot 1072 (“contemporary Venetian brown morocco, gilt arabesque frame sides, with title on upper cover, and initials L.T. on under, gilt and gauffered edges”)

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£1 1s)

● Nathaniel Evelyn William Stainton (1863-1940)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable printed books, illuminated & other manuscripts, and books in fine bindings, London, 26-27 July 1920, lot 527 (“contemporary Venetian dark brown morocco gilt, scroll frames, central circular ornament containing on upper cover the title ‘M. Cato de re rust,’ and on lower the initials L.T.; g.e. tooled with Arabic knots”) [link] [lots 509-552 sold as “The Property of E. Stainton, Esq., Barham Court, Canterbury”]

● Maggs Bros., London - bought in sale (£3 5s)

● Maggs Bros, Catalogue 397: Rare and beautiful books, manuscripts and bindings (London 1920), item 9 (“original Aldine binding of Venetian brown morocco, gilt arabesque frame sides, with title of book in gold letters within circle on upper cover, and initials L. T. on under cover, gilt ornaments at inner and outer angles, gilt and gauffred edges.”) [RBH 397-9]; Catalogue 407: Book bindings: historical and decorative (London 1921) item 409 and Pl. 118 [link]

● J. Irving Davis (1889-1967), formerly trading in London as Davis & Orioli

● Sotheby’s, Printed books, London, 2 April 1985, lot 89 (illustrated; “contemporary Venetian olive morocco, gilt border on sides composed of scrollwork, small fleurons at inner and outer corners, in the centre within a circle composed of fleur-de-lys: on the upper cover title ‘M / Cato / DeRe / Rust.’, on the lower cover initials L T, original spine with title lengthwise in the compartments, gilt gauffred edges of a knotwork design, extreme corners a little repaired, but in excellent condition”) [RBH Atom-89]

● Librairie Thomas-Scheler (Clavreuil) - bought in sale (£5500)

● Paris, Private collection

literature

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.813

Brooker, “Who was L.T. Part I”, op. cit., p.508 no. 1 (“Paris, Private collection”)