Jéronimo Ruiz’s Bindings

Thirty bindings featuring a gold-tooled coat of arms of a rampant lion supporting a silver fleur-de-lys in its dexter paw are now recorded, all but one (an obvious remboîtage) on Italian texts, the great majority printed in the decade 1560-1569. Those that retain their original back have a title lettered horizontally, in the top or in the second compartment, indicating that the books were intended to stand on the shelf in the modern way, upright, backs facing out. The initials “I” and “R” flank the armorial cartouche. These arms and initials were at first misidentified: in 1859, as belonging to James V of Scotland, or to James I of England (whilst James VI of Scotland);1 in 1870, as belonging to the Bouffier family in France;2 however, by 1891 it was recognized that they are the arms of the Ruiz, a family of Spanish origin, resident in Rome (the surname Italianised as Ruis).3 In 1926, G.D. Hobson listed four Ruiz bindings,4 Anthony Hobson in 1953 raised that number to seven,5 and by 1965 “about ten” of “these famous bindings” were known.6 In 1975, Anthony Hobson identified 23 bindings,7 and in 2004 Michel Wittock added another.8 Since then, six more volumes have come to light.9

The Ruiz octavos are simply decorated, with gilt filet borders, and floral tools in the corners. The quartos are more elaborately tooled, some having broad frames, others an arabesque centrepiece and/or cornerpieces. The cartouche or shield enclosing the rampant lion and fleur-de-lys varies, likewise the rampant lion tool. In 1975, Anthony Hobson assigned the bindings to three different Roman shops, of which Maestro Luigi’s was one; when he reconsidered the matter, in 1991, he concluded that they were produced in a single Roman workshop, which he called the “Ruiz Binder”, presuming him to be the successor to Luigi.10 The books, printed between 1533 and 1571, probably were bound within the space of a few years.

G.D. Hobson first drew attention to the Ruiz family chapel in the Roman church of S. Caterina della Rosa dei Funari, where their lion and fleur-de-lys insignia adorn the pilasters and are moulded into the stucco of the chapel arch. In the pavement outside the chapel is a ledgerstone recording details of several family members, which enabled Anthony Hobson in 1975 to identify “I.R.” as Girolamo (Jéronimo) Ruiz. This slab, laid presumably in 1605, is inscribed with a shield bearing the Ruiz arms, the names and dates of two family members: Abate Filippo (Felipe) Ruiz (1512-18 May 1582), who had endowed the chapel, and commissioned its decoration from Girolamo Muziano and Federico Zuccari; and his great nephew, Pietro (Pedro) Ruiz (1573-29 August 1605). Girolamo Ruiz is named thereon as paying for the upkeep of the chapel.11

Detail of the inscribed tablet in floor of Cappella Ruiz, S. Caterina dei Funari, Rome

Above Detail from no. 11 : Florus

Above Detail from no. 18 : Ovid

Above Detail from no. 26 : Strabo

Abate Filippo had trained as a priest and as a lawyer, perhaps in his native Valencia; in Rome, he became archpriest in absentia of Teruel (Zaragoza), scrittore delle lettere of the Penitenzieria Apostolica, correttore of the Archivio della Curia Romana, and held other offices. Together with the noble and wealthy Spaniards Ludovico Torres and Alfonso Diaz, he was a member of the charitable association of Confraternita delle vergini miserabili di S. Caterina della Rosa, founded ca 1543 with the support of Ignatius of Loyola, Filippo Neri, Gaetano da Thiene, and Cardinal Gian Pietro Carafa (later Paul IV). In testaments written in 1566 and in 1576, Abate Filippo made his nephew Girolamo his sole heir, charging him with responsibility for maintaining the Ruiz chapel in S. Caterina dei Funari.12

Girolamo Ruiz was the elder son of Alessandro Ruiz, deputato of the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista in Venice,13 and Taddea Centanni. Born in Venice, he was elected a citizen of Rome by the Consiglio ordinario on 30 July 1565.14 In a deposition made on 23 December 1610, Girolamo claims to be aged 68, so he probably was born in 1542.15 He married Virginia (ca 1578-1611), daughter of the rich Roman banker Giovanni Angelo Crivelli, with whom he had three children: Pietro, a member of the Congregazione dell’Assunta, who died in 1605, aged 32, and was interred in S. Caterina dei Funari; Caterina; and Gaspare.16 Girolamo occupied high offices in the municipal administration, serving as consigliere of Rione Regola in 1568, 1570, 1575, 1576; as consigliere of Rione Ponte in 1576, 1578, 1580, 1581, 1584, 1589; as caporione for Rione Parione in 1569 and for Rione Regola in 1573; and as conservatore in July 1578 for Rione Regola.17 In 1571, Girolamo was one of two sindaci of the Arciconfraternita del Gonfalone.18

Girolamo’s residence was the Palazzo Ruiz, situated between via Giuseppe Zanardelli, via degli Acquasparta, and via della Maschera d’Or, with frontage on the Piazza Fiammetta. He had obtained the property and its opulent contents in 1556, by fidecommesso, upon the death of his great uncle, the apostolic protonotary Girolamo di Belisando Ruiz, and he lived there until 1605.19 Together with his brother, Michele, he ran a literary salon, and probably also held private musical parties (ridotti). The playwright Cristoforo Castelletti dedicated his Rime spirituali (Venice: Heirs of Melchiorre Sessa, 1582) to Girolamo, describing his patron’s household as a “veritable home for the muses and a permanent refuge, where all virtuosi can escape and as it were a safe port from the tempests …”.20 The brothers were joint-dedicatees of Antonio Ongaro’s Alceo fauola pescatoria … Recitata in Nettuno castello de’ signori Colonnesi: et non più posta in luce (Venice: Francesco Ziletti, 1582);21 about the same date, Ongaro dedicated his “Hospitium Musarum”, a poem in 397 hexameters describing the Palazzo Ruiz and its artworks, to little Pietro Ruiz.22 In 1584, Girolamo received the dedication of Castelletti’s Il furbo comedia (Venice: Alessandro Griffio, 1584) and of Luca Marenzio’s Quarto libro de madrigali a cinque voci. Nouamente composti, & dati in luce (Venice: Giacomo Vincenzi & Riccardo Amadino, 1584).23 His wife was lauded in verses published by Muzio Manfredi (Bologna: Alessandro Benacci, 1575).

The surviving books from Girolamo’s library indicate a taste for history, both ancient and modern. He possessed Strabo’s Geography, Caesar’s Commentaries, and works of ancient Roman history by Lucius Annaeus Florus, Polybius, Rufus Festus, Sallustius, and Thucydides, all in in Italian translation, also Bembo’s history of Venice, Biondo’s history of Europe from the plunder of Rome until his own time, Cieza De Leon and Zarate’s histories of Peru and Lopez de Gomara’s of India, likewise in Italian. He owned Ringhieri’s book on courtly entertainments and Scandianese’s on hunting. He seems interested also in philosophy, owning copies of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives, Piccolomini’s compendium of moral philosophy, and similar works by Salviati and Thomagni and Ulloa. And, of course, he had a taste for literature, acquiring the anthologies of the poetry of Luigi Alamanni and Annibale Caro, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Ruscelli’s collection of imprese. As dedicatee, Girolamo presumably was gifted copies of Castelletti and Ongaro’s books, however, those volumes either have been lost, or cannot be recognised.

One binding (no. 30) is an obvious remboîtage. It is decorated by the centrepiece appearing on other bindings (nos. 10, 26 in List below), flanked appropriately by the initials “I R,” and also features a pair of cornerpieces used elsewhere (nos. 17, 22); however, the rampant lion is not supporting a silver fleur-de-lys in its paw (a binder's error, or erased?). The binding now contains a copy of John Wycliffe’s philosophical work Dialogrum (Trialogus), written ca 1382-1384, a text recovered by the Reformers, and printed at Worms in 1525 by a publisher sympathetic to the Reformation cause (he issued the following year Tyndale’s New Testament). This work had been condemned in 1412-1413 by Pope John XXIII, and later was placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

Details from no. 30 : upper and lower covers (the fleur-de-lys normally held in the dexter paw is absent)

Two bindings (Appendix, nos. A1-A2), both displaying the Ruiz arms, but unaccompanied by the letters “I R,” may have been bound for other family members. One covers the 1568 edition of Leandro Alberti’s Descrittione di tutta Italia and is decorated by the same pair of cornerpieces as no. 30, and by the most common of the centre cartouches (used on nos. 1, 4, 7, 8, 11, 13, 17, 24, 27). The other binding covers a 1568 edition, in Latin, of Maurolico’s Martyrology. This book perhaps was bound for Girolamo’s uncle, Abate Filippo Ruiz.24 An empty binding (no. A3) displays the Ruiz arms surmounted by a mitre.25 Anthony Hobson dismissed it, for the reason that he could not identify a member of the family who was ordained bishop.26 At this time, however, priests with the protonotary apostolic title could wear regalia similar to a bishop, including a mitre. Several members of the Ruiz family were protonotari apostolici, among them Girolamo’s uncle, Abate Filippo, and great uncle Girolamo di Belisando Ruiz. The corner ornaments on this empty binding appear on the Manente in the Bibliotheca Brookeriana (no. 17), the Ruscelli at Harvard (no. 22), the Wycliffe at Besançon (no. 30), and the Alberti at Ecouen (No. A1).

1. S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson, Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri, London, 1-15 August 1859, lot 836 (“From the library of James V, King of Scotland, in the contemporary Venetian binding, gilt edges, having his arms and I.R. stamped in gold on sides, which are also ornamented with the fleur-de-lys” [link]); Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, The Hamilton Palace Libraries. Catalogue of the first portion of the Beckford Library, removed from Hamilton Palace, London, 30 June 1882-13 July 1882, lot 1608 (“fine copy from the Library of James VI of Scotland, in purple morocco, gilt gaufré edges, the sides covered with gold tooling having in centre the lion rampant ‘or’ holding the fleur-de-lis ‘argent’ between the initials I.R.” [link]); also: Catalogue of the third portion of the Beckford Library, 2-13 July 1883, lots 2270 [link], 2581 [link]; Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the very choice collection of rare books, illuminated, and other manuscripts, books of prints, and some autograph letters, formed by Mr. Ellis, of 29 New Bond Street, London, 16 November 1885, lots 655 [link], 672 [link], 686 (“from the library of James VI of Scotland, with the Scotch lion and fleur-de-lis, and the initials ‘J.R.’ on the sides in gold” [link]).

2. Joannis Guigard, Armorial du bibliophile: avec illustrations dans le texte (Paris 1870), I, p.109; Nouvel armorial du bibliophile (Paris 1890), II, pp.74-75 [link]. The book from which the arms are taken is not identified.

3. Edward Gordon Duff, Scottish bookbinding, armorial and artistic: A paper read before the Bibliographical Society, February 18, 1918 (London 1920), p.12 (“A word of warning may be given as to some bindings occasionally put forward as specimens made for James VI … The stamp is really that of the Italian family of Ruizi.” [link]). See the entries for the Maurolico (Appendix, no. A2 below) in Charles Isaac Elton, A catalogue of a portion of the library of Charles Isaac Elton and Mary Augusta Elton (London 1891), p.167 (“olive mor., richly tooled, with the arms of the Ruizi family” [link]); and in Burlington Fine Arts Club, Exhibition of bookbindings (London 1891), Case E, no. 22 (“olive morocco; the sides being elaborately tooled in gold; the arms of the Ruizi family of Rome are impressed in the centre of each cover” [link]).

4. Geoffrey Hobson, Maioli Canevari and others (London 1928), p.126 nos. 16-19 (respectively nos. 7, 21, A2, A3 in List below).

5. Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), p.143. Two bindings (nos. 17, 28 in List below) were added to Hobson’s census by Graham Pollard, “Changes in the style of bookbinding, 1550-1830” in The Library, fifth series, 11 (1956), pp.71-94 (p.83; Pollard’s (i) and (iii) are the same binding).

6. Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 589.

7. Anthony Hobson, Apollo & Pegasus: An Enquiry into the formation and dispersal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), pp.219-220: “Appendix IX: Bindings with the arms of Jeronimo Ruiz”, nos. 1-21 (i.e. 23 volumes, as Hobson’s no. 6 is in 3 vols.). In Anthony Hobson & Paul Culot, Italian and French 16th-century bookbindings (Brussels 1991), p.49, “twenty-four volumes are recorded with the Ruiz arms”, the addition apparently the Olaus Magnus (no. 16 in our List).

8. Ovid (unlocated, ex-Michel Wittock). Michel Wittock, “Une reliure inédite pour Jeronimo Ruiz” in E codicibus impressisque, Miscellanea Neerlandica 20 (2004), pp.217-222.

9. Nos. 1 Alamanni (British Library), 4 Caesar (Windsor, Royal Library), 12 Garimberto (Chicago, T.K. Brooker), 25 Sansovino (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek), 27 Thomagni (Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland), 30 Wycliffe (Besançon, Bibliothèque).

10. Hobson & Culot, op. cit., p.49. Also assigned to the Ruiz Binder by Hobson is the copy of Ariosto’s Orlando furioso (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1562), bound for Graf Jakob Hannibal von Hohenems (Altemps; 1530-1587), now Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, Typ 525 62.157. Judging from illustrations, a now unlocated copy of Curtius Rufus De’ fatti d’Alessandro Magno (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1559), likewise bound for Giacomo Annibale Altemps, latterly in the Beckford-Hamilton Palace Library, the collections of William Loring Andrews and Cortlandt F. Bishop, was produced in the Ruiz Binder’s shop.

11. “Hier.s Rvis Patruo Benem. Ac F. Opt. F. C. | Ex Redd.bvs Cappellae”. Transcribed by Pietro Luigi Galletti, Inscriptiones romanae infimi aevi Romae exstantes (Rome 1760), II, p.434 no. 44 [link]; Vincenzo Forcella, Iscrizioni delle chiese e d’altri edificii di Roma dal secolo 11 fino ai giorni nostri, IV (Rome 1874), p.338 no. 814 [link]. Manuel Espadas Burgos, Buscando a España en Roma (Barcelona 2006), p.153 (photograph).

12. 17 December 1566 (Archivio di Stato, Roma, Notai Tribunale Auditor Camerae, atti Johannes Savius, vol. 6469, cc.1037-1041); 21 November 1576 (ASR, Collegio Notai Capitolini, vol. 1427, atti Antonio Maria Rapa, cc.90-94). For the references to the chapel in these testaments, see Rosamond E. Mack, Girolamo Muziano, PhD dissertation, Harvard University, 1972, pp.173-174 (transcriptions); Patrizia Tosini, Girolamo Muziano 1532-1592: dalla maniera alla natura (Rome 2008), pp.175, 360-364 no. A15.

13. Alessandro Ruiz was re-elected to this post on 24 March 1545; see Juergen Schulz, “Titian’s ceiling in the Scuola Di San Giovanni Evangelista” in The Art Bulletin 48 (1966), pp.89-95 (p.90).

14. Archivio Storico Capitolino, Roma, Camera Capitolina, cred. I, t.22 c.126v, and cred. I t.1, c.84r; see Donatella Manzoli, in Antonio Ongaro, Hospitium musarum et carmi latini (Rome 2014), p.8.

15. Il primo processo per San Filippo Neri nel codice Vaticano latino 3798 e in altri esemplari dell’Archivio dell’Oratorio di Roma, Volume IV: Registri del secondo e del terzo Processo (Città del Vaticano 1963), pp.94-95 (“Girolamo Ruiz, del q. Alessandro e di Taddea Centanni, nato a Venezia, di anni 68 circa.”). In a deposition given in Rome in 1607, during the process of beatification of Ignazio di Loyola, Girolamo’s age is given as 65; see Monumenta Ignatiana, ex autographis vel ex antiquioribus exemplis collecta. Series quarta. Scripta de sancto Ignatio de Loyola, Societatis Jesu fundatore (Madrid 1918), II, p.806 no. 22 (“Mag.cus D. Hieronymus Ruiz, romanus, annorum 65, juratus et examinatus die 9 Octobris 1607; ‘mio padre si chiamaua Alessandro Ruiz, et mia madre Thadea Centana, veneta; et uiuo delle mie entrate; io mi confesso ogni domenica et mi comunico nella chiesa del Giesù…’” [link]).

16. Pietro married Vittoria Frangipane, who is named together with their children, Filippo, Pirro, and Virginia, on the tombstone in S. Caterina dei Funari. See Il primo processo per San Filippo Neri, Volume I: Testimonianze dell’inchiesta romana, 1595 (Rome 1957), pp.232-234 no. 61 (deposition of “Petrus Ruisius, filius ill.is d.ni Hieronimi Ruisii et d.nae Virginiae Cribelliae de Ruissa, romanus”, 28 September 1595) and pp.335-337 no. 104 (deposition of Vittoria, 25 October 1595).

17. Claudio De Dominicis, Membri del Senato della Roma Pontificia: Senatori, Conservatori, Caporioni e loro Priori e Lista d’oro delle famiglie dirigenti (secc. X-XIX) (Rome 2009), pp.68, 134, 136. Manzoli, op. cit., p.8.

18. Rossella Pantanella, “Documenti: La Confraternita del Gonfalone” in L’Oratorio del Gonfalone a Roma: il ciclo cinquecentesco della Passione di Cristo (Milan 2002), p.217.

19. Archivio Storico Capitolini, Roma, Camera Capitolina, cred. XIII, I serie, t.88, c.314v and cred. XIII, I serie, t.13, c.192r (cited by Manzoli, op. cit., pp.46-47).

20. “All’illustre, & gentilissimo Sig. Padron mio osseruandissimo, il Sig. Girolamo Ruis … la sua casa è vera stanza delle Muse, & albergo perpetuo, doue tutti i virtuosi dalle tempesti di questa età nemica del tutto delle virtù, quasi in sicuro porto fuggono, & si ricourano …” (A2v).

21. “A gl’ illustri fratelli Il Sig.or Girolamo et il Sig. Michele Ruis … Di Roma, il di 25. di Agosto 1581” (a3v).

22. “Poema Antonii Ongari ad illustrem admodum adolescentem Petrum Ruis”; Manzoli, op. cit., pp.26-27.

23. Castelletti: “All’ illustre, e generoso Sig. Padron mio singolariss. Il Sig. Girolamo Ruis … Di Roma e di casa di V.S. à 15. di Gennaro. 1584” (A3v). Marenzio: “Al Molto Illustre et Generoso Signor Patron mio osservandissimo, il Signor Girolamo Ruis … Di Venetia il dì 5. di Maggio 1584” (A1v). Girolamo’s relations with Casteletti and Ongaro are discussed by Maria Cicala “Il circolo romano dei fratelli Ruis” in Spagna e Italia attraverso la letteratura del secondo Cinquecento: atti del colloquio internazionale, I.U.O.-Napoli, 21-23 ottobre 1999 (Naples 2001), pp.339-387.

24. Filippo’s post-mortem inventory in Archivio di Stato, Roma, Collegio Notai Capitolini, vol. 1427, atti Antonio Maria Rapa, cc.591-601, was located by Tosini, op. cit. 2008, pp.300, 364. Paintings in Filippo's collection are listed, and the inventory possibly refers to books.

25. The binding is illustrated by Emil Hirsch Antiquariat, Buch-Einbände: Literatur und alte Originale … Katalog (Munich [1897]), Pl. 3, and is cited by G.D. Hobson, op. cit., p.126 no. 19, associating it with the “Ruiz family”.

26. Hobson, op. cit., 1953, p.143 (“No Ruizi can be traced in Gams [Series episcoporum ecclesiae catholicae, Ratisbon 1873-1886] although a mitre surmounts the arms on an empty binding”). Hobson excluded it from his 1975 census.

list of bindings

(1) Luigi Alamanni, Opere toscane di Luigi Alamanni al christianissimo re Francesco primo (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1532), bound with Luigi Alamanni, Opere toscane (Venice: Pietro Nicolini da Sabbio for Melchiorre Sessa, 1533)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Thomas Grenville (1755-1846), exlibris

● London, British Library, G. 10621

literature

John Thomas Payne & Henry Foss, Bibliotheca Grenvilliana; Part the second. Completing the catalogue of the library bequeathed to the British Museum by the late Right Hon. Thomas Grenville (London 1878), p.7.

British Library, Database of bookbindings (image; “Binding fragile. 3 raised spine bands, 4 half bands. The fleur de lis in Ruiz’s coat of arms may be tooled in silver. Title tooled in gold directly on to the spine. Ribbon marker”) [binding repaired in 1990, when Grenville exlibris replaced on new paste-down; old free endpapers retained; no other evidence of ownership, except a citation to Fontanini]

(2) Pietro Bembo, Della historia vinitiana di m. Pietro Bembo card. volgarmente scritta. Libri XII (Venice: Gualtiero Scoto, 1552)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● “Ms. inscription on first free endpaper: ‘Isto: di Vinetia’, being an instruction to the binder for the spine title” (opac)

● De Pigis (17C) (Fine bindings) [possibly Jacques Pigis, d. 1676, royal professor of Greek at the Collège Royal de France (1650-1676)]

● All Souls College, Oxford, exlibris [in All Souls Library “by the eighteenth century” (Fine bindings); J. Henderson Smith “The book-plates of All Souls’ College, Oxford” in Journal of the Ex Libris Society 9 (1899), pp.17-23 (College bookplate no. 6)]

● Oxford, All Souls Library, 6:SR.92.d.2 (opac Binding: 16th century Italian brown goatskin over pasteboard, blind- and gilt-tooled with fillets and a decorative roll to form a border with corner fleurons; gilt-stamped armorial centrepiece with initials ‘I’ and ‘R’ on either side; gilt decoration on spine; black leather label at head of spine ‘4’; gilt and gauffered textblock edges. Bound by the Farnese Bindery for I. Ruizi [link])

literature

Bodleian Library, Fine bindings 1500-1700 from Oxford Libraries (Oxford 1968), no. 14 (“More than twenty bindings, on books dated between 1516 and 1569, are now recorded bearing the present arms, which belonged to the Ruizi family, of Spanish origin but domiciled in Rome. The initials of a member of this family, I.R. (not yet identified), flank the central cartouche in nearly all these bindings … A point of interest is the early use of titling on the spine, which in this and the Goldschmidt and Fürstenberg examples, and also on four Ruizi bindings in the Bodleian (8° I 277-279 BS; Vet. F1 f. 97), is part of the original tooling; under the front pastedown of this All Souls volume is written the actual lettering ‘Isto: di Vinetia’ which the finisher was to follow”)

Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: an enquiry into the formation and dispersal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), pp.219-220 (“Appendix IX: Bindings with the arms of Jeronimo Ruiz”, no. 13)

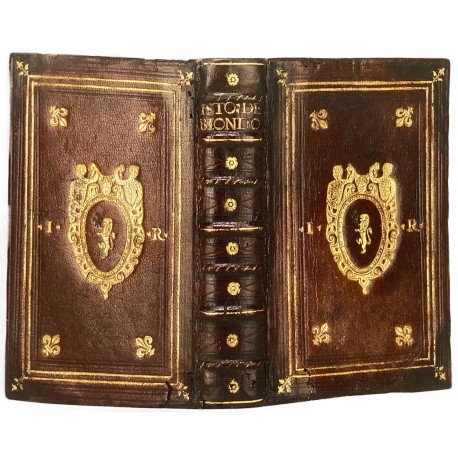

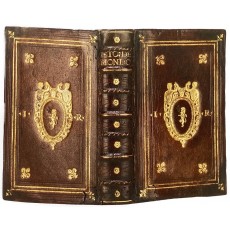

(3) Flavio Biondo, Le historie del Biondo, da la declinatione de l’imperio di Roma, insino a tempo suo (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1547)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Sydney Richardson Christie-Miller (1874-1931)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable early English & Scottish works on law and history from the renowned library formerly at Britwell Court, Burnham, Bucks., the property of S.R. Christie Miller, London, 22-24 March 1926, lot 35 (“contemporary dark brown morocco, line panelled tooling on sides with a flower stamp at the exterior and a fleur-de-lis at the interior angles, Ruizi arms in centre (a lion rampant holding a fleur-de-lys) flanked by the initials I.R. gauffred edges” [link])

● E.P. Goldschmidt, London, exlibris - bought in sale (£9 10s; E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., Stock Books 1921-1981, #8446, in Grolier Club Library [link]); their Catalogue 9: Rare and valuable books (London 1926), item 164 (“within an oval cartouche the arms of Jacopo Ruizi flanked by the letters J. R.” [link]) [RBH 9-164]; Catalogue 73: A choice of various books (London 1944), item 24 & Pl. 2 [RBH 73-24] [Goldschmidt Stock Books, op. cit., sold to Abbey 3 February 1944, £19]

● John Roland Abbey (1896-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 152

● D. McDonald Booth, London - bought in sale (£38)

● Bernard Quaritch, Catalogue 933: Printed books & manuscripts (London 1973), item 30 (£185; “… initials I.R. (i.e. the arms and initials of Jacopo Ruiz) … with the book-labels of E. Ph. Goldschmidt and J.R. Abbey … The initials were once said to stand for Iacobus Rex and these bindings to have belonged to James I of England: the lion was the lion of Scotland, holding a fleur-de-lys because the king’s mother had been Queen of France”)

● Michel Wittock (1936-2020)

● Christie’s, The Michel Wittock Collection, Part I: Important Renaissance Bookbindings, London, 7 July 2004, lot 20

● unsold [RBH 6996-20]

literature

E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author's collection (London 1928), no. 213 and Pl. 83

Ilse Schunke, “Die vier Meister der Farnese-Plaketteneinbände” in La Bibliofilia 54 (1952), pp.57-91 (p.84 no. 12)

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 945 bis (“London, E. Ph. Goldschmidt (1928)”)

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 2

Bibliotheca Wittockiana, Cinq siècles d’ornements dans le décor extérieur du livre 1515-1983 (Brussels 1983), no. 7

Anthony Hobson & Paul Culot, Italian and French 16th-century bookbindings (Brussels 1991), no. 17

Paul Culot, “La reliure en Italie et en France” in Bibliotheca Wittockiana, Musea Nostra - 38 (Brussels 1996), p. 25 (illustrated)

(4) Gaius Iulius Caesar, Commentarii di Gaio Giulio Cesare, tradotti di latino … per Agostino Ortica della Porta (Venice: Francesco Lorenzini, 1563)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom (1819-1901)

● Windsor, Royal Library, RCIN 1081327 (website, “Bound in brown sheepskin, gold-tooled; edges gilt and gauffered … The arms and initials on this binding are those of Jerónimo Ruiz, resident in Rome in the 1560s” [link])

literature

Unpublished

(5) Annibale Caro, Rime del commendatore Annibal Caro (Venice: Aldo II Manuzio, 1569)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● James Bohn, Catalogue of ancient and modern books in all languages (London 1840), item 1488 (£1 11s; “in rich old gilt binding, gilt edges, with the initials I. R. on the sides, similar to the volumes from the Library of King James I”)

● Alexander Douglas, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767-1852)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, The Hamilton Palace Libraries. Catalogue of the first portion of the Beckford Library, removed from Hamilton Palace, London, 30 June 1882-13 July 1882, lot 1608 (“fine copy from the Library of James VI of Scotland, in purple morocco, gilt gaufre edges, the sides covered with gold tooling having in centre the lion rampant ‘or’ holding the fleur-de-lis ‘argent’ between the initials I.R.” [link])

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£12) [link]

● F.S. Ellis, London

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the very choice collection of rare books, illuminated, and other manuscripts, books of prints, and some autograph letters, formed by Mr. Ellis, of 29 New Bond Street, London, 16 November 1885, lot 655 (“old brown morocco super extra, the sides embossed in gold with corner and centre ornaments, from the library of James VI of Scotland, with his initials J.R., gilt edges, the back restored” [link])

● Ellis (Gilbert Ifold Ellis & James Perram Scrutton, trading as Ellis), London - bought in sale (£6)

● Giuseppe Martini, Lugano

● Libreria antiquaria Hoepli & W.S. Kundig, Bibliothèque Joseph Martini, Première partie, Lucerne, 27-29 August 1934, lot 59 & Pl. 51 (“armes de Iacopo Ruizi de Rome avec ses initiales. I.R.” [link])

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.62 (opac Legatura in pelle, su assi lignee; sui piatti cornici e fregi in oro, con iniziali ‘I[acopo] R[uiz’ in oro e tondo con leone rampante reggente giglio in oro. - Tagli goffrati in oro. [link])

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 947 & Pl. 159

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 21 (incorrectly states “No initials”)

(6) Pedro de Cieza De Leon, La prima parte dell’historie del Perù (Venice: Giordano Ziletti, 1560)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, 8° I 277 BS (opac [link])

literature

Fine bindings 1500-1700 from Oxford Libraries, no. 14 (cited [link])

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 6 [see nos. 14-15 in this list]

(7) Dante Alighieri, Comedia del diuino poeta Danthe Alighieri, con la dotta & leggiadra spositione di Christophoro Landino (Venice: Bernardino Stagnino for Giovanni Giolito, 1536)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Sydney Richardson Christie-Miller (1874-1931)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a collection of rare and valuable books and tracts chiefly Latin, French and Italian of the XVth and early XVIth centuries, London, 31 July-3 August 1917, lot 364 (illustrated; “contemporary Venetian binding of red morocco, blind and gilt stamps on back, elegant tooled sides ornamental borders, with gilt figures of Cupid and Fortune, centre cartouches enclosing a lion supporting a fleur-de-lis with initials I.R. gilt gauffered edges, genuine and in fine state”; illustrated) [RBH Jul311917-364]

● J. & J. Leighton, bought in sale (£43)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the first portion of the famous stock of the late Mr. W. J. Leighton (who traded as Messrs. J. & J. Leighton), of 40 Brewer Street, Golden Square, W. (sold by order of the Executor), London, 14-19 November 1918, lot 254 (“contemporary Venetian binding of red morocco, blind and gilt stamps on back, elegant tooled side, ornamental borders, with gilt figures of Cupid and Fortune, centre cartouches enclosing a lion rampant holding a fleurdelis with initials J.R., gilt gauffered edges, large copy in fine and genuine state” [link])

● James Tregaskis, London - bought in sale (£30); their The 837th Caxton Head catalogue (London 1921), item 234 & Pl.; Caxton Head catalogue 848: 16th Century illustrated books (London, December 1921), item 67 (£63 [link]); Caxton Head catalogue 935: Rare and interesting books (London 1927), item 210 [link]); The One thousandth Caxton Head catalogue (London 1931), item 6 (£60; “Venetian red polished morocco … in the centre a fine cartouche enclosing a lion rampant holding a fleur-de-lis, the Arms of the Ruizi family of Rome. There is also at each corner a solid Aldine tool in gold; above and below the cartouche are the figures of Cupid and Fortune with the initials I.R. (Jac Ruizi) on each side, gilt gauffered edges”)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, illuminated and other manuscripts, autograph letters & historical documents, mainly of Continental origin, London, 18 December 1936, lot 94 (“contemporary Roman red polished morocco, gilt and blind stamped tooling on back, the sides tooled with a broad ornamental border of double-line interlaced strapwork, the spaces being filled with fine tooling of solid ornaments, in the centre a fine cartouche of the heavy Roman type enclosing a lion rampant holding a fleur-de-lys, the arms of the Ruizi family of Rome. There is also at each corner a solid tool in gold; above and below the cartouche are figures of Cupid and Fortune with the initials J. R. (Jac Ruizi) on each side, gilt gauffred edges”) [lots 78-124 are “Another property”; RBH 18Dec1936-94]

● Davis & Orioli, London - bought in sale (£9); their Catalogue 165 (London 1961), item 69 (illustrated)

● Georges Heilbrun, Paris (Needham)

● New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, 59345 (opac Brown calf gilt, bound for Jacopo Ruiz with his arms, by the ‘Arabesque binder’; in grey cloth box [link])

literature

Geoffrey Hobson, Maioli Canevari and others (London 1928), p.126 no. 16

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 944 & Pl. 158

Howard Nixon, Sixteenth-century gold-tooled bookbindings in the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York 1971), p.182 (“A more elaborate binding for Ruiz was given to the Library by Miss Julia Wightman, which has the same cartouche, with Cupid above and Fortune below, and a border interrupted with knotwork that is found on some of the Apollo and Pegasus bindings. The book is a Dante, Comedia 1536, printed at Venice (PML 59345)”)

Sixteenth Report to the Fellows of the Morgan Library 1969-1971 (New York 1973), p.64 (“Purchase: Miss Julia P. Wightman”)

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 11

Paul Needham, Twelve centuries of bookbindings 400-1600 (New York 1979), no. 74

(8) Dio Cassius, Dione. Delle guerre de romani. Tradotto da m. Nicolo Leoniceno et nuouamente stampato (Venice: Pietro Nicolini da Sabbio, 1548)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone Libri, Count Libri-Carrucci (1803-1869)

● S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson, Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri, London, 1-15 August 1859, lot 836 (“From the library of James V, King of Scotland, in the contemporary Venetian binding, gilt edges, having his arms and I.R. stamped in gold on sides, which are also ornamented with the fleur-de-lys” [link])

● Boone, London - bought in sale (£3 4s)

● British Museum [ownership stamp is the smaller version of type III (1929-1973), red ink handstamp with date “12 Apr 60”; see “A Guide to British Library Book Stamps” - link]

● London, British Library, C.46.b.34

literature

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 3

British Library, Database of bookbindings [image]

(9) Diogenes Laertius, Delle vite e sententie de’ filosofi illustri. Di nuouo dal greco ridutto nella lingua italiana per i Rossettini da Prat’Alboino (Venice: Domenico Farri, 1566)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Andre Desvouges & L. Giraud-Badin, Livres anciens, rares et précieux, manuscrits et imprimés. Incunables, impressions aldines, auteurs italiens des XIVe, XVe et XVIe siècles, riches reliures anciennes, Paris, 28-29 June 1927, lot 255 (“mar. brun, comp. de fil. dor et à froid, avec fleurons aux angles intérieurs et extérieurs, dos orné, tr. dor. et ciselées (Rel. anc.), Exemplaire aux armes et au chiffre de Jérôme Ruscelli.”)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.162 (opac Sul recto della carta di guardia anteriore, a matita, ‘relié pour Jacopo Ruiz v. Goldschmidt 213 et 4xxxiii.’ [sic]”; “Ai piatti, stemma di Jacopo Ruiz”; “Legatura in pelle. Piatti decorati con cornici a filetto e fiori angolari dorati. Nello specchio, stemma citato. Dorso a 7 nervi con titolo e fregi dorati e a secco. Taglio goffrato e dorato [link])

literature

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 10

(10) Lodovico Dolce, Le dignità de’ consoli, e de gl’imperadori, e i fatti de’ Romani, e dell’accrescimento dell’imperio, ridotti in compendio da Sesto Ruffo, e similmente da Cassiodoro, e da m. Lodouico Dolce tradotti & ampliati (Venice: Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari, 1561)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Baptiste Galanti, Paris (De Marinis)

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 945 & Pl. 158

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 15 (“by Luigi”)

(11) Lucius Annaeus Florus, De fatti de Romani dal principio della città per insino ad Augusto Cesare (Venice: Heirs of Pietro Romani & Co., 1546 [colophon: January 1547]), bound with Polybius, Polibio Del modo dell’accampare tradotto di greco per m. Philippo Strozzi. Calculo della castrametatione di messer Bartholomeo Caualcanti. Comparatione dell’armadura, & dell’ordinanza de romani & de macedoni di Polibio tradotta dal medesimo. Scelta de gli apophtegmi di Plutarco tradotti per m. Philippo Strozzi [part 2:] Eliano De’ nomi et de gli ordini militari tradotto di greco per m. Lelio Carani (Florence: Lorenzo Torrentino, 1552), bound with Sextus Rufus Festus, Libro di Sesto Ruffo huomo consulare, a Valentiniano Augusto, dell’historia de Romani. Nuouamente tradotto de latino in volgare (Venice: Agostino Bindoni, 1544), bound with Andrea Domenico Fiocco, Il Fenestella d’i sacerdotii, e d’i magistrati romani. Tradotto di latino alla lingua toscana, al Magnifico M. Angelo Motta (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de Ferrari, 1544)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● William Phelp Perrin (1743-1820), exlibris

● J. & J. Leighton, London; their Catalogue of early-printed & other interestng books, manuscripts & fine bindings: Part VIII (London [ca 1908?]), item 5137 & p.1410 (£20; “Italian red morocco … enclosing the arms of James VI. of Scotland (afterwards James I. of England), viz: the Lion of Scotland (in gold) holding a fleur-de-lis (in silver), flanked by the Royal initials I.R. … A rare and remarkable binding done about 1590 for James VI. of Scotland before he succeeded to the English throne” [link])

● Charles William Dyson Perrins (1864-1958), exlibris

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the magnificent library principally of early printed and early illustrated books formed by C.W. Dyson Perrins, Esq., of Davenham, Malvern, and now sold by his order. The first portion: books printed in Italy, London, 17-18 June 1946, lot 255 (“the arms of the Ruizi family of Rome”)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£65)

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982)

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York; their Catalogue 107: Italy, Part II: Books printed 1501 to c. 1840 (New York [1984]), item 135 ($7500)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1989) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2200; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 37; reoffered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana VIII, Paris, 3-17 December 2025, lot 127, link]

literature

Alfred W. Pollard, Italian book-illustrations and early printing; a catalogue of early Italian books in the library of C.W. Dyson Perrins (London 1914), nos. 263, 265, 264, 273 (“Italian red morocco stamped on front and back with the arms of the Ruizi, and initials I.R.” [link])

Edward Gordon Duff, Scottish bookbinding, armorial and artistic: A paper read before the Bibliographical Society, February 18, 1918 (London 1920), p.12 (“A word of warning may be given as to some bindings occasionally put forward as specimens made for James VI … The stamp is really that of the Italian family of Ruizi. An example of this binding is on a copy of Florus: Dei Fatti Romani, Venice, 1547, in the possession of Mr. Dyson Perrins.”)

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 17

Tammaro De Marinis, Die italienischen Renaissance-Einbände der Bibliothek Fürstenberg (Hamburg 1966), pp.66-67

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 1

(12) Girolamo Garimberto, Concetti di Girolamo Garimberto, Et d’altri degni Autori; Raccolti da lui per scriuer, & ragionar familiarmente (Venice: Domenico Farri, 1571)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● F.B., supralibros (these initials stamped over I.R.)

● Librairie Paul Jammes, Paris, 1990

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1990) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2355]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part VII, London, 11 July 2025, lot 1699, unsold against estimate £2400-£3200 [link]; reoffered by Sotheby's, Bibliotheca Brookeriana VIII, Paris, 3-17 December 2025, lot 140 [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (€1016) [RBH pf2525-140]

literature

Unpublished

(13) Pier Francesco Giambullari, Historia dell’Europa (Venice: Francesco Senese, 1566), bound with: Lodovico Guicciardini, Commentarii di Lodouico Guicciardini delle cose più memorabili seguite in Europa (Venice: Domenico Farri, 1566)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● unidentified owner, crowned cypher inkstamp [see Govi catalogue, image, link]

● Cardinal Giuseppe Renato Imperiali (1651-1737), inkstamp “Ex. Bibl. Ios. Ren. Card. Imperialis” on the first title-page

● Bibliothecae Josephi Renati Imperialis Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae (Rome 1711), “Appendix Bibliothecae”, p.554 (“Giambullari Pierfrancesco. Storia d’Europa dall’anno 800. fino al 913. Venezia per Francesco Senese 1566. In 4°”)

● De Pigis, ownership inscription on first title-page (17C) [compare no. 2, Bembo in this list]

● Count Orazio Sanminiatelli (1894-1972) (Hobson)

● Govi Rare Books LLC, List January 2017: Sixteenth-Century Books (New York 2017), item 9 (“On the front pastedown purchase note ‘F 30’”)

● Philobiblon, Auction 7: Rare and ancient books, including an important collection of Aldine editions and Renaissance bindings, Rome, 22 June 2016 lot 267 (“Legatura coeva romana realizzata per Jeronímo Ruiz dal ‘Ruiz Binder’, marocchino bruno su piatti in cartone, decorata a secco e in oro. Al centro di entrambi i piatti lo stemma di Ruiz ‘un lione rampante che tiene un fleur-de-lis’ stampato in oro in cartouche riccamente decorato, ai lati le iniziali ‘I.R.’ Dorso con tre doppi nervi, sottolineati da filetto in oro, alternati a tre nervi semplici, con filetti dorati in diagonale. Scomparti decorati da filetti a secco e fregi in oro. Titolo in caratteri dorati al secondo scomparto. Tagli dorati e cesellati, con motivi diagonali” [link]) [estimate €8000-€15,000; RBH 62216-267]

● Philobiblon, One thousand years of bibliophily, II: The Sixteenth century (New York [2018]), item 137

● PrPh Books, New York [archived web description and illustration: “Contemporary Roman binding executed by the so-called ‘Ruiz Binder’. Light brown morocco over pasteboards. Covers within a rich border of gilt and tooled fillets, and gilt floral roll. Elaborate gilt cornerpieces. The arms of Ruiz - a lion rampant, stamped in gold, holding a fleur-de-lis, stamped in silver - in a cartouche flanked by the initials ‘I R’ in the centre of both covers. Traces of ties. Spine with three double bands, decorated with gilt fillets, alternating with four single bands, decorated with short gilt diagonals. The title in the second compartment, a gilt rosette on a pattern of blind horizontal and diagonal lines in each of the other compartments. Edges gilt and gauffered with knotwork.”)

● Forum, Fine books, manuscripts and works on paper, London, 22 January 2020, lot 50 [link; RBH 1053-50]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (£5000) (estimate £4000-5000)

literature

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 19

(14) Francisco Lopez de Gomara, La seconda parte delle Historie generali dell’India (Venice: Giordano Ziletti, 1557)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, 8° I 278 BS (opac [link])

literature

Fine bindings 1500-1700 from Oxford Libraries, op. cit., no. 14 (cited [link])

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 6 [see nos. 6, 15 in this list]

(15) Francisco Lopez de Gomara, Francisco, La terza parte delle historie dell’Indie. Nella quale particolarmente si tratta dello scoprimento della prouincia di Incatan detta nuoua Spagna (Venice: Giordano Ziletti, 1566)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, 8° I 279 BS (opac [link])

literature

Fine bindings 1500-1700 from Oxford Libraries, op. cit., no. 14 (cited [link])

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no 6 [see nos 6, 14 in this list]

(16) Olaus Magnus, [probably Storia d’Olao Magno arciuescouo d’Uspali [!] de’ costumi de’ popoli settentrionali. Tradotta per m. Remigio Fiorentino (Venice: Francesco Bindoni, 1561)]

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

literature

Hobson & Culot, op. cit., p.49 (as Ruiz owning “Olaus Magnus’s [work] of Scandinavia”)

(17) Cipriano Manente, Historie di Ciprian Manente da Oruieto (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1561)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Étienne Baluze (1630-1718), signature on title-page

● Gabriel Martin, Bibliotheca Baluziana, seu, Catalogus librorum bibliothecae V. Cl. D. Steph. Baluzii Tutelensis quorum fiet auctio due lunae and mensis maii anni 1719 & seqq. à secundâ pomeridianâ ad vesperam, in aedibus defuncti, viâ vulgò dictâ de Tournon, Paris, 8 May 1719, p.297 lot 3787 (“mar.”)

● Charles Spencer, 5th Earl Sunderland (1706-1758)

● Puttick & Simpson, Bibliotheca Sunderlandiana: Sale catalogue of the truly important and very extensive library of printed books known as the Sunderland or Blenheim library, Third portion, London, 17-27 July 1882, lot 7929 (“contemporary morocco, the sides covered with rich gold tooling, with a shield in the centre containing a lion supporting a fleur-de-lis, and having the initials I. R. on each side, gilt and gauffred edges, a fine specimen of contemporary Italian binding” [link])

● Ellis & White, London - bought in sale (£5 7s 6d) [link]

● Frederick Startridge Ellis, London

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the very choice collection of rare books, illuminated, and other manuscripts, books of prints, and some autograph letters, formed by Mr. Ellis, of 29 New Bond Street, London, 16 November 1885, lot 672 (“from the Library of James VI., with his initials, J.R., on the sides, old morocco super extra, the sides elaborately gilt tooled, gilt gauffered edges … The present volume, though slightly repaired at the back, is otherwise in perfect condition, the tooling being bright and fresh. The centre ornament on each side is a shield, with a lion rampant, embossed in gilt, holding a ‘fleur-de-lis’, blind-tooled, in his paw, the initials ‘I.R.’ being on either side of the shield” [link]) [sale occasioned by the retirement of Ellis’ partner, David White]

● Harvey - bought in sale (£9)

● Arthur Jeffrey Parsons (1856-1915); Agnes Stockton Royall Parsons (1861-1934) [widow, consignor of the library]

● American Art Association, Illustrated catalogue of selections from the private library of the late Arthur Jeffrey Parsons of Washington, D.C., New York, 24 January 1923, lot 37 (“old red morocco … center panel with heavy gilt floral corner ornaments with arms of Gaspard Bouffier stamped in gilt and blind in center, initials I R on either side of the shield; back panelled with blind tooled geometrical designs and gilt floral patterns; gilt edges gaufred in elaborate interlaced design; signature, - ‘Stephanus Baluzius Tutelensis’ on title … The initials I R have not been identified, and are perhaps those of a later owner.”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($35) [American Book Prices Current, link]

● Giuseppe Martini, Florence & Lugano

● Libreria antiquaria Hoepli, Bibliothèque Joseph Martini. Deuxième partie, Zurich, 21-23 May 1935, lot 129 & Pl. 56 (“reliure contemporaine romaine … au milieu un écusson orné portant les armes de Iacopo Ruiz” [link])

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, fine bindings, Oriental manuscripts and miniatures, autograph letters and historical documents, London, 8-10 November 1954, lot 97 (“… by the Farnese bindery for I. Ruizi … in fine fresh condition”) [lots 84-100 offered as “Other Properties”]

● Davis & Orioli, London - bought in sale (£42); their Catalogue 151 (London [1955]), item 16a (£90; “This is a very elaborate binding far more richly decorated than the one reproduced in plate 88 of [Goldschmidt’s] work”)

● Librairie Lardanchet, Paris; their Catalogue 50: Catalogue de beaux livres anciens et modernes (Paris 1956), item 3783 (FF 125,000; reproduced, citing “Goldschmidt, Reliures, no. 213”)

● Sandbergs Bokhandel, Stockholm; their Catalogue 13: Rare books & prints (Stockholm 1966), item 47 ($1600 / Cr8225; illustrated; “an elaborate specimen of a ‘Ruizi binding’ in perfect condition”)

● Georges Heilbrun, Paris; their Catalogue 31: Cent vingt livres 1475-1875 (Paris 1969), item 40 (FF 10,000; “Reliure romaine de la ‘Farnese bindery’ pour I. Ruizi”)

● Charles Filippi (d. 2000) (Hobson)

● Ader Tajan & Pierre Meaudre, Bibliothèque Charles Filippi. Première partie, Paris, 21 October 1994, lot 48 (estimate FF 80,000-90,000)

● Librairie Lardanchet, Paris; their Beaux livres anciens et modernes - Février 1995 (Paris 1995), item 8 (FF 95,000)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1995) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2321]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, Part VII, London, 11 July 2025, lot 1759 [link]; reoffered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana VIII, Paris, 3-17 December 2025, lot 200, [link]

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 948

Graham Pollard, “Changes in the style of bookbinding, 1550-1830” in The Library, fifth series, 11 (1956), pp.71-94 (p.83 no. 1)

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 14 (“M. Charles Filippi”)

Federico Macchi & Livio Macchi, Atlante della legatura italiana: il Rinascimento: XV-XVI secolo (Milan 2007), pp.160-161 & Tav. 60

(18) Publius Ovidius Naso, Le metamorfosi di Ouidio ridotte da Giovanni Andrea dell’Anguillara in ottaua rima, editio terza (Venice: Francesco De Franceschi, 1569), bound with: Tito Giovanni Scandianese, Quattro libri della caccia, di Tito Giouanni Scandianese (Venice: Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari & fratelli, 1556)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Milan, Società Unitaria, Centro Studi Sociali Biblioteca (stamp at end of first volume, removed from first title) (Christie’s)

● Sotheby’s Italia, Libri e stampe, Milan, 25 March, 1994, lot 430 (“marocchino rosso del secolo XVII impresso e dorato, stemma e monogramma al centro dei piatti”)

● Michel Wittock (1936-2020)

● Christie’s, The Michel Wittock Collection, Part I: Important Renaissance bookbindings, London, 7 July 2004, lot 61 [estimate £12,000-18,000; unsold; RBH 6996-61]

● Alde, Collection Michel Wittock. Septième partie, Paris, 14 November 2017, lot 13 (“Superbe et très rare reliure romaine en maroquin décoré aux armes de Jerónimo Ruiz, exécutée à Rome vers 1569 par l’atelier baptisé ‘Ruiz Binder’ par Anthony Hobson. On recense aujourd’hui vingt-neuf reliures de cette provenance, y compris celle-ci, qui ne figurait pas dans le census établi par Anthony Hobson avant la publication de l’article que Michel Wittock lui a consacré en 2004”) [RBH 25868-13]

● unsold (estimate €10,000-12,000)

literature

Paul Culot, “La reliure en Italie et en France” in Bibliotheca Wittockiana, Musea Nostra - 38 (Brussels 1996), p. 25 (illustrated)

Michel Wittock, “Une reliure inédite pour Jeronimo Ruiz” in E codicibus impressisque, Miscellanea Neerlandica 20 (2004), pp.217-222

(19) Alessandro Piccolomini, Della institutione morale di m. Alessandro Piccolomini libri XII (Venice: Giordano Ziletti, 1560)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Riccardo Bruscoli, Florence (De Marinis; “stimato antiquario fiorentino Riccardo Bruscoli”)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of fine bindings and valuable printed books, London, 28 February 1966, lot 93 (“contemporary Roman binding with the arms and initials of I. Ruizi, olive morocco gilt, leaf and acorn border, flower at each inner corner, the arms of Ruizi in a cartouche flanked by his initials, gilt rosette and blind leaf tools in the compartments of the spine, edges gilt and gauffered, two ties missing, spine a little wormed”) [this is the Stefan Mendl sale, however lot 93 among “Other Properties”; RBH TUNIS-93]

● Georges Heilbrun, Paris - bought in sale (£60) [American Book Prices Current, link]

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 3010 bis

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 4 (“by Luigi”)

(20) Polybius, Polibio historico Greco dell’imprese de’ Greci, de gli Asiatici, de’ Romani, et d’altri. Con due fragmenti delle republiche, et della grandezza di Roma, & con gli undici libri ritrouari di nuouo, tradotti per M. Lodouico Domenichi (Venice: Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1564)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Anthony Morris Storer (1746-1799) (?)

● Eton, Eton College Library, Cq.4.1.05 (opac 16th century (third quarter) gold-tooled morocco. ? Farnese bindery. Border and four corners of foliage tools. Central cartouche, supported by human figures, containing lion rampant, holding silver fleur de lys, device of Ruiz family of Rome. Initials “I. R.”, probably Jacopo Ruiz. Gauffered edges. Re-backed (? for Storer) [link])

literature

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 8

(21) Innocenzio Ringhieri, Cento giuochi liberali et d’ingegno (Bologna: Anselmo Giaccarelli for the author, 1551)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Bernard Quaritch, London; their Catalogue 93: A catalogue of fifteen hundred books remarkable for the beauty or the age of their bindings (London 1888), item 64 (£6 6s; “the initials I.R. on the sides probably designate the author; but the arms, a lion standing upright with a fleur-de-lis, argent, in his claw, are not apparently those belonging to his name” [link])

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, London, Catalogue of valuable books and manuscripts including a portion of the library of a noble lady and selections from other libraries, London, 1-4 July 1895, lot 1188 (“brown morocco covered in gilt ornamental tooling, with the device and initials of James V. of Scotland on sides in imitation of contemporary binding, g. and gauffred edges”) [offered among “Other Properties”]

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£1 10s)

● Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a further portion of the valuable library collected by the late Charles Fairfax Murray, Esq., of London and Florence, 17-20 July 1922, lot 874 (illustrated; “morocco, the sides of a contemporary binding very neatly laid on, olive morocco, 3-line fillet and narrow arabesque border round edges, interlacing arabesque corner-pieces stamped in relief on a gold ground, the centre decorated with leafy arabesques and a centre cartouche containing a lion rampant holding a fleur-de-lys flanked by the initials I.R.” [link]) [RBH Jul171922-874]

● Leo S. Olschki, Florence - bought in sale (£6 10s)

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Bernard Quaritch, London; their Catalogue 951 (London 1975), item 44 (£260; illustrated; “olive morocco gilt, the sides of the original, contemporary binding inlaid and consisting of an outer border of stylized foliage enclosing a fine central panel with interlacing arabesque cornerpieces stamped in relief on a gold ground, the centre decorated with leafy arabesques and a cartouche containing aa lion rampant holding a fleur-de-lis flanked by the initials I.R. (for Jacopo Ruiz); gilt gauffered edges … With the Fairfax Murray book-label)”)

literature

Charles Fairfax Murray, A list of printed books in the library of Charles Fairfax Murray (London 1907), p.199 (“Sm. 4to. modern br. morocco, richly gilt, with device and initials of James V. in imitation of a XVIth Cent. binding” [link])

Bibliothèque nationale et Musée des arts décoratif, Exposition du livre Italien Mai-Juin 1926: Catalogue des manuscrits, livres imprimés, reliures (Paris 1926), no. 968 (“Reliure contemporaine en maroquin fauve, plats richement ornés: dans le milieux un lion soutenant une fleur-de-lis d’argent; à coté les initiales I.R. De la bibl. C. Fairfax Murray. A M. Leo S. Olschki, Florence”)

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.126 no. 17

De Marinis, op. cit, no. 945 & Pl. 159 (“Firenze, T. De Marinis”)

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 12

(22) Girolamo Ruscelli, Le imprese illustri con espositioni, et discorsi (Venice: Francesco Rampazetto for Damiano Zenaro, 1566)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● J. Pearson & Co., Very choice books including an extremely important series of historical bindings together with original and illuminated manuscripts, etc (London [1901?]), item 99 (150 guineas; “From the library of James VI. Of Scotland…” [link; this Harvard copy of Pearson’s catalogue received 1902]) [catalogue entered in Monthly Bulletin of Books Added to the Public Library of the City of Boston, September 1902, p.362; link]

● John Walker Ford (1838-1921)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a portion of the valuable library of J.W. Ford, Esq. of Enfield Old Park, London, 5-7 May 1904, lot 391 [link]

● McMartin - bought in sale (£75) [Book Prices Current, link]

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable books & manuscripts, ancient and modern, London, 7-10 December 1904, lot 903 (“Venetian morocco, sides covered with a richly gilt design of arabesques, with the arms of James VI. Of Scotland in the centre, gilt back, gold tooled edges … From the library of James VI of Scotland. Bound at Venice for James before the death of Elizabeth, and consequently while King of Scotland only. The binding is a masterpiece of Venetian art. In the centre is the Lion of Scotland holding the fleur-de-lys (which James bore in right of his mother, daughter of Mary of Guise, better known as Mary Stuart), with the initials ‘I.R.’ The Scots Lion is four times separated, surrounded by 13 fleur-de-lys” [link]) [lots 886-925 offered as “The Property of a Gentleman”]

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£51) [Book Prices Current, link]; their Catalogue 268: An illustrated catalogue of books printed during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (London 1909), item 626 (illustrated; “From the library of King James VI of Scotland. The book was magnificently bound at Venice for James before the death of Queen Elizabeth, and consequently while he was King of Scotland only. The binding is a masterpiece of Venetian art. In the centre is the lion of Scotland holding the fleur-de-lys (which James bore in right of his mother, daughter of Mary of Guise, better known as Mary Stuart, with the letters I.R.”; Catalogue 367: A catalogue of English and foreign bookbindings (London 1921), item 307 (£63; “in a beautiful Venetian binding of citron morocco, the sides covered with a richly gilt design of arabesques, with the arms of the Ruizi family of Florence and the initials I.R. in the centres, gilt back, gilt gauffred edges”)

● Col. William E. Moss (1875-1953)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the very well-known and valuable library the property of Lt.-Col. W.E. Moss of the Manor House, Sonning-on-Thames, Berks., who is changing his residence, London, 2-9 March 1937, lot 1227 (“in a contemporary Roman binding … a shield bearing a lion rampant supporting a fleur-de-lys [arms of the Ruiz family], initials ‘I.R.’ at sides…”)

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£28); their Catalogue 538: A catalogue of books: Americana, bibles and liturgies, early printed books, French and English literature, natural history books (London 1937), item 253 (£45; “in a fine Roman binding of brown morocco, the sides covered with large gilt stamps of arabesque design and stamps of lions and fleur-de-lys, in the centre within an oval the arms of the Ruizi family of Florence, a lion rampant supporting a fleur-de-lys, and the initials I.R.; the back tooled with strips of crested acorns, gilt gauffred edges; back repaired at head and tail and corners mended”)

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969), (JA 2358)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection; the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 589

● W.H. Schab, New York - bought in sale (£160); their Catalogue 39: Early illustrated & scientific books (New York 1965), item 49 & Pl. 49 (“Sold”; “… one of the seven existing Roman bindings which were executed in the Farnese bindery for Jacopo Ruiz”)

● Philip Hofer (1898-1984)

● Cambridge, MA, Harvard College, Houghton Library, Typ 525 66.758 (opac Full contemporary brown morocco, with gilt arms & initials of Jacopo Ruiz, gilt leaf ornament, lions, & fleurs-de-lis; edges gilt & gauffered [link])

literature

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J. R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), no. 69

Ruth Mortimer, Catalogue of books and manuscripts [in Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, Harvard College], Part 2: Italian 16th century books (Cambridge, MA 1974), no. 459 (“gilt arms of Jacopo Ruiz in the center of each cover … There might be a connection between Jacopo Ruiz and the Michael Ruyz who composed the verses to Charles V printed on leaf Q2v … Gift of Philip Hofer”) [Miguel Ruiz de Azagra; see now Maria Cicala “Il circolo romano dei fratelli Ruis” in Spagna e Italia attraverso la letteratura del secondo Cinquecento (Naples 2001), esp. pp.368-369]

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 18

(23) Gaius Sallustius Crispus, La historia di Gaio Sallustio Crispo, nuouamente tradotta dal Signor Paulo Spinola (Venice: Giovanni Andrea Valvassori, 1563)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Stockholm, Kungliga biblioteket, RAR:129 C d b Övers. Ital. 1563 (opac [link])

literature

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 7

(24) Leonardo Salviati, De dialogi d’amicizia di Lionardo Saluiati libro primo al nobilissimo signor Alamanno Saluiati (Florence: Heirs of Bernardo I Giunta, 1564), bound with Giuseppe Orologi, L’ingratitudine di m. Gioseppe Horologgi, diuisa in tre ragionamenti (Venice: Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari, 1562), bound with: Giuseppe Orologi, L’inganno dialogo di m. Gioseppe Horologgi (Venice: Gabriele Giolito De Ferrari, 1562)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Benjamin Bathurst, 2nd Viscount Bledisloe (1899-1979)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, important literary manuscripts, autograph letters, London, 3 April 1950, lot 10 (contemporary Roman black morocco gilt, the arms of a member of the Ruizi family within a cartouche in gilt on sides, flanked by his initials IR, worn, upper joint cracked, edges gilt and gauffered) [lots 1-69 are Bathurst property; RBH CHERRY-10]

● Georges Heilbrun, Paris (Hobson)

● Librairie Thomas-Scheler, Paris; their Le Goût de l’Amateur: Livres reliés pour quelques bibliophiles célèbres (Paris 2007), item 5 (€15,000; “relié à Rome vers 1565, par le Ruiz Binder pour Jeronimo Ruiz"); [New York bookfair catalogue, 2022] ($18,000; “Gold-tooled olive-brown morocco over pasteboard, blind and gilt fillet border, Ruiz armorial stamp at centre flanked by his initials. I.R., fleur-de-lis within the coat-of-arms stamped in silver, 4 double and 3 single spine bands tooled alternately with gilt fillet or short diagonals, single flower-head in compartments, the second and third with title, edges gilt and gauffered”)

literature

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, p.219 no. 9

(25) Francesco Sansovino, Della agricoltura di m. Giouanni Tatti lucchese libri cinque (Venice: Francesco Sansovino, 1560)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Einbandsammlung, Ebd 109-8 (opac [link])

literature

Schunke, op. cit., p.91 (“Zu den Arbeiten des Mauresken-Meisters kann ergänzend noch ein Einband für Jacopo Ruiz aus der Einbandsammlung in Berlin genannt werden. (109-8). Er ist durch seinen frühen Titelaufdruck auf dem Rücken interessant.”)

(26) Strabo, La prima parte della Geografia di Strabone, di greco tradotta in volgare italiano da m. Alfonso Buonacciuoli gentilhuomo ferrarese (Venice: Francesco Senese, 1562), bound with Strabo, La seconda parte della Geografia di Strabone di greco tradotta in volgare italiano da m. Alfonso Buonacciuoli (Ferrara: Francesco Senese, 1565)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● William Beckford (1760-1844) (?)

● Alexander Douglas, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767-1852)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, The Hamilton Palace Libraries. Catalogue of the third portion of the Beckford Library, removed from Hamilton Palace, London, 2-13 July 1883, lot 2270 (“2 vol. in 1, in contemporary brown morocco, covered with Grolier gold tooling, having as centre ornament a lion rampant, holding a fleur-de-lis and the initials I. R. gilt gaufré edges” [link])

● James Bain, London - bought in sale (£8)

● Samuel Putnam Avery (1822-1904); exlibris “For the Frances Taylor Pearsons Plimpton Library, Wellesley College. In Memoriam, from Samuel P. Avery, New York, Fby. 12, 1901” (Jackson)

● Wellesley, MA, Wellesley College, Plimpton collection, q P600 (opac Brown morocco, Grolieresque gold tooling, gilt gauffered edges; center ornament of a lion rampant, holding a fleur-de-lis and the initials I.R. (i.e. Iacopo Ruiz of Rome?) [link])

literature

Henri Pène du Bois, Four private libraries of New York (New York 1892), p.46 (“in brown morocco ornamented with a Grolieresque pattern having in the center a lion passant holding a fleur-de-lis, and marked with Roman initials I.R., made for King James I … The book is the ‘Geographia’ of Strabo, 1562-1565, and was No. 2270 of the Beckford Hamilton Palace auction-sale catalogue. It is a precious example of ancient British handicraft” [link])

Margaret Hastings Jackson, Catalogue of the Frances Taylor Pearsons Plimpton collection of Italian books and manuscripts in the library of Wellesley College (Cambridge, MA 1929), pp.274-276 no. 600 & Fig. 29 (“From the library of King James I while James VI of Scotland” [link])

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 16 & Pl. 22

(27) Giovanni David Thomagni, Dell’eccellentia de l’huomo sopra quella de la donna libri tre (Venice: Giovanni Varisco & compagni, 1565), bound with Alfonso de Ulloa, Dialogo della degnità dell’huomo. Nel quale si ragiona delle grandezze & marauiglie, che nell’huomo sono: & per il contrario delle sue miserie e trauagli (Venice: Francesco Rampazetto for Giovanni Battista & Melchiorre Sessa, 1564)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● William Beckford (1760-1844)

● Alexander Douglas, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767-1852)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Hamilton Palace Libraries. Catalogue of the third portion of the Beckford Library, removed from Hamilton Palace, London, 2-14 July 1883, lot 2581 (“old Venetian morocco, gilt gaufré edges, with the arms of Gaspard Bouffier in gold on sides in 1 vol.” [link])

● Ellis & White, London - bought in sale (£2 14s)

● F.S. Ellis, London

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the very choice collection of rare books, illuminated, and other manuscripts, books of prints, and some autograph letters, formed by Mr. Ellis, of 29 New Bond Street, London, 16 November 1885, lot 686 (“2 vols. in 1, in old olive morocco extra, gilt edges, from the library of James VI. of Scotland, with the Scotch lion and fleur-de-lis, and the initials ‘J.R.’ on the sides in gold” [link])

● James Bain, London - bought in sale (£4 18s)

● Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl Rosebery (1847-1929), exlibris

● Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, Ry.III.d.28(1) [Thomagni], Ry.III.d.28(2) [Ulloa] (opac [link])

literature

Catalogue of the library at Barnbougle Castle (Edinburgh 1901), p.278 (“From the library of James VI of Scotland, with the Scotch lion and fleur-de-lys and the initials ‘J.R.’ on the side in gold. 2 vols. in 1. Small 8°”) [no separate entry for Ulloa]

George P. Johnston, Catalogue of the early & rare books of Scottish interest in the library at Barnbougle Castle (Edinburgh 1923), p.258 (Thomagni) and p.263 (Ulloa)

(28) Thucydides, Gli otto libri di Thucydide atheniese, delle guerre fatte tra popoli della Morea, et gli atheniesi (Venice: al segno del Laocoonte, 1550)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Oxford, Bodleian Library, Vet. F1 f. 97 (opac [link])

literature

Fine bindings 1500-1700 from Oxford Libraries, op. cit., no. 14 (“A point of interest is the early use of titling on the spine, which in this and the Goldschmidt and Fürstenberg examples, and also on four Ruizi bindings in the Bodleian (8° I 277-279 BS; Vet. F1 f. 97), is part of the original tooling” [link])

Pollard, “op. cit., p.83 no. 2.

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 5

(29) Agustín de Zárate, Le historie del sig. Agostino di Zarate contatore et consigliero dell’imperatore Carlo V dello scoprimento et conquista del Perù (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de Ferrari, 1563), bound with Xenophon, Le guerre de’ greci, scritte da Senofonte, nelle quali si continoua l’historia di Thucidide (Venice: Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1562 [colophon: In Vinetia, 1550])

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros and initials IR

● Robert Wynter Blathwayt (1850-1936) [lots 1-125 in sale below offered as “The Property of Mr Robert W. Blathwayt, of Dyrham Park, Chippenham”]

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of important and interesting historical & ecclesiastical manuscripts … valuable old & modern printed books including selections from the libraries of Robert W. Blathwayt, Esq. (Dyrham Park, Chippenham), and Cecil Sebag Montefiore, Esq., London, 20-21 November 1912, lot 35 (“original Venetian brown morocco, gilt ornamental back, rich gilt borders of arabesques with corner fleurons, a figured shield in centre enclosing a lion rampant holding a fleur-de-lis with initials I.R.; gilt and gauffred edges, back slightly damaged above and below” [link])

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£13 5s)

● Louis-Alexandre Barbet (1850-1931)

● Henri Baudoin, Maurice Ader & Librairie Giraud-Badin, Bibliothèque de feu M. L.-A. Barbet. Première partie, Paris, 13-14 June 1932, lot 154

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 3300)

literature

De Marinis, op. cit, no. 94

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 17

(30) [apparent remboîtage] John Wycliffe, Jo. Wiclefi viri undiquaque pijs dialogorum libri quatuor ([Worms]: [Peter II Schöffer], 1525)

provenance

● Jerónimo Ruiz (ca 1542-after 1610), armorial supralibros (?) and initials IR [here the Ruiz lion does not hold a fleur-de-lys in its dexter paw]

● Besançon, Bibliothèque, REL.16.121 (201920) (opac rel., maroquin brun, doré : grands fers d'angles azurés, fers courbes, au centre armes et monogramme I R (plats), fleurs de lis (dos), 16e s. [link])

literature

Mémoire Vive patrimoine numérisé de Besançon, [link]

bindings for other ruiz family members

(A1) Leandro Alberti, Descrittione di tutta Italia di f. Leandro Alberti bolognese, nella quale si contiene il sito di essa, la qualità delle parti sue, l’origine delle città, de' castelli, & signorie loro con i suoi nomi antichi, & moderni; i monti, i laghi, i fiumi, le fontane & i bagni; le minere, et l’opere marauigliose in quella dalla natura prodotte; i costumi de’ popoli; & gli huomini famosi, che di tempo in tempo l’hanno illustrata. Aggiuntaui la descrittione di tutte l’Isole pertinenti all’Italia appartenenti, con i suoi disegni, collocati a i luoghi loro con ordine bellissimo. Con le sue tauole copiosissime (Venice: Ludovico Avanzi, 1568)

provenance

● Ruiz, armorial supralibros [no initials are tooled on either side of the arms]

● Ecouen, Musée national de la Renaissance, ECL12037 (image [link])

literature

Unpublished

(A2) Francesco Maurolico, Martyrologium reueren. domini Francisci Maurolyci abbatis Messanensis multo quam antea purgatum, et locupletatum (Venice: Lucantonio II Giunta, 1568)

provenance

● Ruiz, armorial supralibros [as no initials are tooled on either side of the arms, this binding perhaps belonged to Jerónimo’s uncle, Felipe Ruiz (1512-1582)]

● unidentified owner, inscription “Laureti Leoncini (ex-libris manuscrit)” (Lardanchet)

● Bernard Quaritch, Catalogue of books in historical or remarkable bindings from the libraries of sovereigns or of distinguished private collectors (London 1883), item 12986 (£20; “in the original morocco binding, splendidly gilt and ornamented on the sides and back, with the arms of Lorenzo Leoncini, whose name is written on the title-page … This is a magnificent specimen of Venetian binding, the pattern of the ornament being of a grand style, and the use of gold luxuriant to almost an extreme degree”); Catalogue of the monuments of the early printers in all countries (London 1888), item 37167 [link]

● Charles Isaac Elton (1839-1900); Mary Augusta Elton (1838-1914)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the valuable library of books & manuscripts of the late Mrs. Charles Elton, London, 1-2 May 1916, lot 360 (“contemporary Venetian brown morocco, the sides covered with rich and elaborate gilt tooling of geometrical scroll borders, with panels of leafy branches and fleurons, with inner centre ornaments bearing a shield with a lion rampant holding a fleur-de-lis, ? Gaspard Bouffier (see Guigard), each cover lettered with the word ‘martyrologium’; g.e. corners neatly repaired, otherwise in fine state and a fine specimen, in a new embroidered silk bag, signature of ‘Laureti Leoriani’ on title” [link])

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£30 10s) [Book Auction Records, link]

● Herschel V. Jones (1861-1928)

● Anderson Galleries, Catalogue of the library of Herschel V. Jones, New York, 2-3 December 1918, lot 158 (“in a remarkable 16th century dark brown morocco binding, exquisitely tooled in gold on sides and back, broad floriated outside border, inside of which the four corner-pieces are in the shape of triangles, each consisting of branch and leaf ornaments into which is incorporated the head of a dolphin. Four other ornaments and six rosettes are placed between these triangles. Between the two lower triangles the word Martyrologium is lettered in gold. The central piece is an oval ornament containing a standing lion holding a fleur-de-lys, the crest used by James before he became King of England. Both covers are the same. The corners of the back and sides are very skilfully repaired, and it is in splendid preservation … Only two other bindings with similar crest (attributed to James VI.) are known, one in possession of a London dealer, and another, described by Quaritch, 1909, Cat., p.240” [link]) [RBH 1375-158]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($180) [American Book Prices Current, link]

● Laure Eugénie (née Pillet) Belin

● René Boisgirard & Librairie Giraud-Badin with Charles Bosse, Bibliothèque de Mme Th. Belin: Précieux manuscrits à miniatures, livres à figures des XVIe, XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, riches reliures anciennes armoriées, Paris, 19-20 February 1936, lot 94 & Pl. 34 (“mar. brun, comp. De fil … Exemplaire recouvert d’une superbe reliure du temps, richement ornée, aux armes de Jacopo Ruiz, de Rome. Les gardes sont modernes.” [link; image, link])

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 1860)

● Librairie Lardanchet, Livres anciens du XVIe au XIXe siècle (Paris 2007), item 9 (illustrated; €24,000)

● Christie’s South Kensington, Fine printed books and manuscripts, London, 25 November 2014, lot 27 (“contemporary brown morocco by Jerónimo Ruiz, lavishly decorated in gilt (extremities very lightly rubbed, lacking ties), gilt edges”) [online, image]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (£8750)

literature

Charles Isaac Elton, A catalogue of a portion of the library of Charles Isaac Elton and Mary Augusta Elton (London 1891), p.167 (“olive mor., richly tooled, with the arms of the Ruizi family” [link]) [copy cited in The Library, 1893, p.347 (unsigned review of Elton catalogue): “A Martyrologium of 1568, in olive morocco, with the arms of the Ruizi family, has a very similar border, but gains a more massive appearance from the inner compartment being almost entirely covered”]

Burlington Fine Arts Club, Exhibition of bookbindings (London 1891), Case E, no. 22 (illustrated; “Italian binding of the 16th century; olive morocco; the sides being elaborately tooled in gold; the arms of the Ruizi family of Rome are impressed in the centre of each cover” [link])

Exposition du livre italien, mai-juin 1926, op. cit., no. 969 (“Maroquin brun, plats richement ornés, présentant au milieu un lion rampant soutenant une fleur-de-lis d’argent. A Mme Th. Belin, Paris”)

G. Hobson, op. cit., p. 126 no. 18

A. Hobson, op. cit. 1975, no. 20

(A3) Empty binding

provenance

● Ruiz, armorial supralibros [here the Ruiz arms are surmounted by a mitre, signifying a priest with the protonotary apostolic title, perhaps Jerónimo’s uncle, Felipe Ruiz (1512-1582)]

● Emil Hirsch Antiquariat, Katalog 15: Buch-Einbände. Litteratur und alte Originale. Mit 12 Tafeln (Munich [1897]), item 44 & Pl. 3 (“Hervorragend schöner Rothmaroquin-Deckel der italien. Frührenaissance mit reicher ornamental hervorragender Vergoldung. Mit Bischöfl. Wappen (aufsteigender Löwe im Schild). Ca. 1580. (32 : 22 cm). M[ark] 120. Abbildung siehe Tafel III”)

literature

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.126 no. 19

A. Hobson, French and Italian collectors, op. cit., p.143 (“No Ruizi can be traced in Gams although a mitre surmounts the arms on an empty binding”)

Needham, op. cit., p.236 (“I have not seen the binding…”)