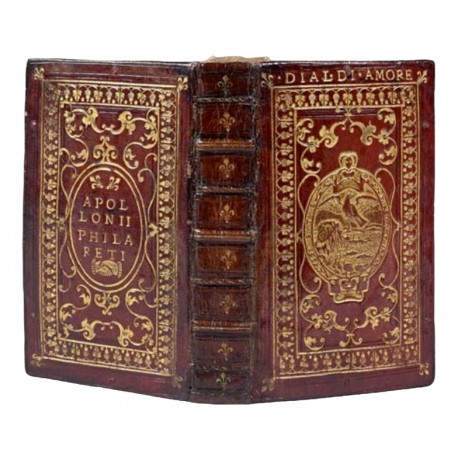

Apollonio Filareto’s Bindings

The appetite for Filareto’s bindings has been regularly stimulated by lists of the extant volumes, which show them to be much rarer than the “Apollo and Pegasus” bindings with which they are often compared. At present, seventeen Filareto bindings are recorded. In 1926, G.D. Hobson published a list of 9 volumes, recapitulated the same year by E.P. Goldschmidt;1 in 1948, that number was raised to 11 by Nicolas Rauch;2 in 1960, to 13 by Tammaro De Marinis, his list recapitulated in 1975 by Anthony Hobson.3 In 1991, Hobson added a 14th volume to his list; a 15th binding was subsequently added by Federico Macchi.4 Two more are added here. Six of the recorded Filareto bindings are still in private hands: three in the Bibliotheca Brookeriana, the 1535 Aldine Lactantius (last seen in the Esmerian sale, in 1972), an empty binding (thought to have once housed the second part of the 1497 Aldine Iamblichus, last seen in the Wittock sale, in 2004), and the poorly-preserved Petrarca (rebacked, corners repaired) which entered the market in September 2023.

Eleven of the recorded Filareto bindings cover Venetian books, five are on Lyonese imprints, and one is a manuscript (in an altered binding, possibly a remboîtage). The earliest was published in 1497 and the latest in 1542. The books have the owner’s name lettered in gold in an oval compartment on the lower cover: apollonii philareti, and on the upper cover, beneath the gold-tooled name of the author or title, is his proud device: a medallion of an eagle soaring above a perilous seashore, and motto: Procul Este (Virgil, Aeneid, VI, 258). Although all the bindings feature the same medallion, it is generally accepted now that they were produced in three different shops: ten bindings in Rome, by Niccolò Franzese;5 three in Rome, by Marcantonio Guillery;6 and four in Northern Italy, perhaps in Bologna, by an anonymous shop.7 All three bindings in the Bibliotheca Brookeriana are from Niccolò Franzese’s shop. All three incorporate decoration by a lily tool and (on lower covers) a clasped hands tool, these symbolising their owner’s allegiance to the Farnese family.

The intaglio stamp for applying the impresa evidently belonged to Filareto, and was lent to the bookseller who sold him the book and made the binding. Filareto possibly designed the device himself, or it may have been conceived by his friend and colleague in Farnese service, Claudio Tolomei, who is the probable inventor of the “Apollo and Pegasus” device employed by Giovanni Battista Grimaldi. The maker of the plaquette is unknown. G.D. Hobson thought he might be one of the gem-engravers then working for Pope Paul III; Anthony Hobson was uncommitted.8

The books seem to have been bound in batches at different times, in 1542-1544 in Rome, then in 1545-1547 in Northern Italy, where Filareto had travelled with his master, Pier Luigi Farnese. Filareto was arrested in Piacenza on 10 September 1547 by the assassins of Pier Luigi, and sent to Milan for imprisonment. His library evidently was left behind, as some volumes entered the Dominican monastery of S. Giovanni in Canale, in Piacenza.9 After three years’ incarceration, Filareto was released, and returned to Rome. In 1552, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, Pier Luigi’s son, bestowed on Filareto the arcipretura of S. Sisto in Viterbo, and he died there in 1569.10

1. Geoffrey Hobson, Maioli, Canevari and others (London 1926), pp.112-119, Pls. 6, 54-56. E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author's collection (London 1928), I, pp.280-281.

2. Nicolas Rauch, Catalogue 1: Catalogue de très beaux livres (Mies, Vaud [Switzerland] 1948), item 43.

3. Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), nos. 814-826. Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: an enquiry into the formation and disposal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), pp.91-95.

4. Anthony Hobson & Paul Culot, Italian and French 16th century bookbindings (Brussels 1991), pp.18-21 no. 4. Federico Macchi, Legature di pregio nella biblioteca “A. Mai” (website, link).

5. Bound by Niccolò Franzese: 1. Bembo, 2. Castiglione, 3. Catullus, 4. Dio Cassius, 5. Martialis, 6. Sententiae, 7. Terentius Afer, 8. Thucydides, 16. Judah Abravanel, 17. Petrarca.

6. Bound by Marcantonio Guillery: 12. Della Casa, 13. Ptolomaeus, 14. Iamblicus.

7. Bound in Northern Italy: 9. Lactantius, 10. Macrobius, 11. Vettori. Macchi provisionally adds no. 15 Ovid to this group, noting however that some of the tooling on the restored lower cover could be Roman. In 1975, Anthony Hobson placed the binder in “Parma or Piacenza” (op. cit., p.93); in 1991, he placed him “probably in Bologna” (op. cit., p.21).

8. Anthony Hobson, Humanists and bookbinders: the origins and diffusion of the humanistic bookbinding, 1459-1559 (Cambridge 1989), p.122. Anthony Hobson, “Plaquettes on bookbindings” in Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 22, Symposium Papers IX: Italian Plaquettes (Washington, DC 1989), pp.165-173 (p.171).

9. Four bindings certainly entered the convent library, as they retain a relevant inkstamp and/or inscription: 3. Catullus, 6. Sententiae, 7. Terentius Afer, 11. Vettori. Two other bindings have evidence of deletion of that stamp or inscription: 4. Dio Cassius, 10. Macrobius.

10. Giuseppe Signorelli, Viterbo nella storia della Chiesa (Viterbo 1940), II, pp.362-363.

bindings decorated with a plaquette of the owner’s impresa

(1) Pietro Bembo, Epistolarum Leonis decimi pontificis maximi nomine scriptarum libri XVI (Lyon: Thibaud Payen, 1540)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Nicolas Yemeniz (1783-1871), exlibris [William Poidebard, Armorial des bibliophiles de Lyonnais, Forez, Beaujolais et Dombes (Lyon 1907), pp.709-711]; Nicolas Yemeniz, Catalogue de mes livres (Lyon 1865-1866), II, p.257 no. 2399 [collection bought en bloc by the Parisian bookseller Antoine Bachelin, financed by Ambroise Firmin-Didot]

● Delbergue-Cormont & Librairie Bachelin-Deflorenne, La bibliothèque de M. N. Yemeniz, Paris, 9-31 May 1867, lot 2399 (“veau à compartiments. (Ancienne reliure.) On lit sur les plats: Apollonii Philareti”) [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 51)

● François-Gustave-Adolphe Guyot de Villeneuve (1825-1898)

● Maurice Delestre & Édouard Rahir, Catalogue des livres manuscrits et imprimés, des dessins et des estampes du cabinet de feu M. Guyot de Villeneuve. Deuxième partie, Paris, 25-30 March 1901, lot 1117 (“mar. citron, compartiments, tr. dor. (Rel. lyonnaise du XVIe siècle.) On lit sur un des plats: Apollonii Philareti…”) [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 425)

● George Dunn (1865-1912), exlibris

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the valuable & extensive library formed by George Dunn, Esq. (deceased), Woolley Hall, near Maidenhead; sold by order of the executors. The second portion: comprising early manuscripts and printed books and old bindings, London, 2-6 February 1914, lot 816 (“… somewhat discoloured, but genuine and in very good state (from the Yemeniz library)”)

● J. & J. Leighton, London - bought in sale (£17) [according to the J. & J. Leighton stockbook (British Library Add Ms 45168, f.109 recto), sold to E.P. Goldschmidt for £25 + 10% commission]

● E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., London [E.P. Goldschmidt stockbook (Grolier Club), #1317, original (1923) and rewritten (1929) stockbook entries do not state source; sold to Wilmerding, 28 February 1933]

● Lucius Wilmerding (1880-1949)

● Parke-Bernet Galleries, A Selection of precious books from the library of the late Lucius Wilmerding: Exhibition in Geneva … in Paris … in London (New York 1951), no. 433; Parke-Bernet Galleries, The notable library of the late Lucius Wilmerding. Part II, New York, 5-6 March 1951, lot 247 [RBH 1230-247]

● Arthur Rau, Paris - bought in sale ($900)

● André Langlois (1873-1975), exlibris

● Librairie Patrick et Elisabeth Sourget, Chartres

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1997) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2112; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library: Magnificent Books and Bindings, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 10]

literature

Geoffrey Hobson, Maioli, Canevari and others (London 1926), p.116 no. 1 & Pl. 6 (“Present ownership: Mr. E.P. Goldschmidt”)

Bibliothèque nationale et Musée des arts décoratif, Exposition du livre italien, mai-juin 1926: catalogue des manuscrits, livres imprimés, reliures (Paris 1926), no. 936 (“A M. E.P. Goldschmidt, Londres”)

E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author’s collection (London 1928), no. 205 & Pl. 78

Lucius Wilmerding, A catalogue of an exhibition of Renaissance bookbindings held at the Grolier Club from December 17, 1936 to January 17, 1937: with an address delivered by Lucius Wilmerding (New York 1937), pp.20, 52 no. 60 & Pl. VII

Arthur Rau, “André Langlois (Contemporary Collectors XIII)” in The Book Collector 6 (1957), pp.129-143 (cited, p.131)

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 814 & Pl. 133

Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: an enquiry into the formation and disposal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), p.92 (“Apollonio Filareto’s bindings”, no. 1: “Paris, M. André Langlois”)

(2) Baldassarre Castiglione, Il libro del corteggiano del conte Baldesar Castigilione, nuouamente stampato, et con somma diligenza reuisto (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1541)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Graf Bernard Ignaz von Martiniz (1603-1685), student of theology in Siena and Rome in 1635, donation inscription “Ex dono Illmi et Excellmi Dni Dni Bernardj Ignatij Comitis à Martinitz supremj Burggravy in Regno Böema”

● Theatine monastery St. Kajetán, Prague, inscription “Bibliothecae Sta Ma Cler. Reg. Aetinganae” on title-page, exlibris “Domus S. Mariae de Divina Providentia Cler. Reg. Pragae” pasted to verso [Bohumír Lifka, Exlibris a supralibros v českých korunních zemích v letech 1000 až 1900 (Prague 1980), p.159]

● Strahov Monastery, Prague, deleted inscription “Monasterij Strahoviensis Pragae” on paste-down, associated (?) shelfmarks “H.VIII.323”, “VII.63”, “15 E XV a36 F 3”

● circular ink stamp on title-page, lettered regiae biblioth. acad. pragen. with double-headed crowned eagle

● Prague, University Library, 13.J.1145 (opac, link)

literature

Ernst Kyriss, “Bookbindings in the libraries of Prague” in PBSA 3 (1950-1951), pp.105-130 (p.129: “The general execution and the decoration of the cover is similar to the one reproduced by Hobson [Maioli, Canevari and others (London 1926)] as Plate 54 [on Dio Cassius, see below]”)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 815

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.92 no. 2

(3) Gaius Valerius Catullus, Catullus. Tibullus. Propertius (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, March 1515)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Convento di S. Giovanni in Canale, Piacenza (Dominicans), lettered inkstamp “Bibliothecae S Io in canalibus Placentiae” on title-page [G. Hobson; speculation that Filareto had abandoned his books there when he was arrested]

● Bibliothèque de la Faculté de Médecine, Montpellier, manuscript catalogue of the library of the written in 1819 (by the librarian, Gordon), no. J 217

● allegedly De Bure, Catalogue des livres faisant partie du fonds de Librairie ancienne et moderne de J.J. et M. J. De Bure Frères … Septième et dernière partie (Paris 1840), p.71 item 22 (FF 40; “m. cit. a compart. avec des rubans. anc. rel. On voit sur le plat, d’un côté, un emblême avec la devise Este procul; et de l’autre Apollonii Philareti”) [catalogue cited by Guillaume Libri, Lettre de M. Libri à M. Barthélemy Saint-Hilaire, administrateur du Collège (London 1850), pp.xiii-xiv - link]

● allegedly Payne & Foss, A Catalogue of Greek and Latin Books on Sale by Payne and Foss, 81, Pall Mall (London 1845), item 16 (“Catullus, Tibullus et Propertius, beautiful copy in old morocco, gilt on the sides with strings £2 12s 12mo”) [entry from Libri, op. cit. 1850, p.xiii; cf Malo-Renault, op. cit.: “Aux catalogues cités, on pourrait ajouter celui de ces deux libraires publié en 1846 (Auteurs grec et latins), ou le volume porte le no. 613.”)]

● Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone, Count Libri (Libri-Carrucci) (1803-1869)

● Commendeur & Jannet, Catalogue de la bibliothèque de M. L****, Paris, 28 June-4 August 1847, lot 316 (“Très bel exemplaire dans sa première reliure du XVIe siècle, faite à l’imitation de celles de Grolier, et parfaitement conservée. Sur chaque plat il y a un écusson, l’un desquels porte cette légende: ‘Apollonii Philareti’.”) [link]

● Librairie A. Franck, Paris - bought in sale (FF 55); their Catalogue d’une belle collection de livres rares et curieux principalement en langue Italienne, Espagnole, Provençale, Française, Grecque, Latine, etc. (Paris [1848]), p.12 item 199 (FF100) [link]; Guillaume Libri, op. cit., 1850, p.xi [link]

● Montpellier, Bibliothèque de la Faculté de Médecine, J 217 (A. Hobson)

literature

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.117 no. 2 (“one of the volumes Libri was accused of having stolen from the Bibliothèque de l’École de Médecine, Montpellier”)

Jean Malo-Renault, “Notes sur quatre reliures du XVIe siècle. Un Apollonio Filareto retrouvé à Montpellier” in Les Trésors des bibliothèques de France 5 (1933), fasc. XX, pp.195-200 & Pl. 67 (“Il y aurait donc lieu de croire, avant tout examen, que le volume ne provient pas de Montpellier, et nous verrons plus loin ce qu’il faut penser du grattage d’estampille. Pour ce qui est des étiquettes spéciales de la bibliothèque de l’École de médecine a Montpellier qui furent retrouvées au domicile du bibliomane et dont l’une portait la cote d’un Catulle appartenant à cette bibliothèque, on peut tout aussi bien supposer qu’elles avaient été détachées par Libri et conservées en vue d’un vol future, comme les notes et calques pris par lui sur certains manuscrits de dépôts publics.”)

Hellmuth Helwig, Handbuch der Einbandkunde (Hamburg 1953-1955), I, p.175 Fig. 56

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 816

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.92 no. 3

(4) Dio Cassius, Dione. Delle guerre de Romani. Tradotto da m. Nicolo Leoniceno, & nuouamente stampato (Venice: Giovanni Farri & Bros, 1542)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● probably Convento di S. Giovanni in Canale, Piacenza (Dominicans), cancelled inscription or stamp [Nixon: “Strip cut from foot of title page, where other Filareto bindings have this ownership stamp”]

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of printed books, and illuminated and other manuscripts, London, 20-23 July 1921, lot 663 (consigned as “Property of a Gentleman”)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£5)

● William E. Moss (1875-1953)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the very well-known and valuable library the property of Lt.-Col. W.E. Moss of the Manor House, Sonning-on-Thames, Berks., who is changing his residence, London, 2-9 March 1937, lot 619 (both covers illustrated)

● Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£82)

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the celebrated library; the property of Major J.R. Abbey. Part III, London, 19-21 June 1967, lot 1817 (illustrated)

● Martin Breslauer, London - bought in sale (£2000)

● New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, 57631 (Gift of Julia P. Wightman)

literature

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.117 no. 3 & Pl. 54

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), no. 59

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 818

Maria Lanckorońska, “Der große Canevari-Mythos” in Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 1969, pp.300-307 Fig. 3

Pierpont Morgan Library, Fifteenth Report to the Fellows (New York 1969), pp.42-44

Howard Nixon, Sixteenth-century gold-tooled bookbindings in the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York 1971), pp.28-31 no. 8

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.92 no. 4

Paul Needham, Twelve centuries of bookbindings: 400-1600 (New York & London 1979), no. 48

Federico & Livio Macchi, Atlante della legatura italiana: Il Rinascimento (XV-XVI secolo) (Milan 2007), pp.148-149 Tav. 54 (“Mercato antiquario”)

(5) Marcus Valerius Martialis, Martialis (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano), 1517

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Rome, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 55.C.35

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 821

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.92 no. 5

(6) Sententiae et proverbia ex poetis Latinis. His adjecimus sententias prophanas, ex diversis scriptoribus, in communem puerorum usum, collectas (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1541), bound with: Plato, Gemmae, sive illustriores sententiae, ad excolendos mortalium mores & vitas recte instituendas à nicclao liburnio veneto collectae. Quibus adiecimus quoque M.t.ciceronis sententias elegantißimas quasque ex libris ipsius diligenter selectas, iamque tertio editas, ac locupletatas. Item, ex terentii comoediis, quotquot extant, sententias atque paroemias elegantiores omnes (Basel: Robert Winter, 1542)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Convento di S. Giovanni in Canale, Piacenza (Dominicans), inkstamp, cancelled inscription (opac “Sul frontespizio, antica nota di possesso ad inchiostro cancellata ‘Conventus […]’ e timbro “Bibliothecae S. Io. Canalibus Placentiae’”)

● Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Stamp.De.Marinis.144(int.1) (opac “Legatura in cuoio. Piatti decorati con fregi in oro e a secco. Nello specchio del piatto anteriore, incisione dorata in medaglione abitato da aquila con ali spiegate che vola sul mare, due delfini e uno scoglio e motto “procvl este”; sul margine superiore in oro “setet et proverb”. Nello specchio del piatto posteriore, incisione dorata in medaglione “apollonii philareti” e due mani unite. Dorso a 7 nervi decorato con cordami in oro. Taglio dorato.” [link])

literature

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.118 no. 7

Exposition du livre italien, op. cit., no. 937 (“A M. T. De Marinis, Florence”)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 823

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.92 no. 6 & Pl. B

(7) Publius Terentius Afer, Terentii Comoediae, multo, quam antea, diligentius emendatae (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, May 1541)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Convento di S. Giovanni in Canale, Piacenza (Dominicans), inkstamp (opac “Bibliothèque de Piacenza (cachet caché par une étiquette)”)

● Sir Thomas Rokewood Gage, 8th Bt (1810-1866) (?)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of an extraordinary selection of rare & valuable books & manuscripts, from the library of … Sir Thomas Gage … and other collectors, London, 25-26 June 1867, lot 345 (“beautiful copy in the original olive morocco, covered with gold tooling, lettered on obverse of cover, Terentius, below which is the medallion device (eagle, rock, fish, &c) of Apollonius Philaretus (A. Filareto), and having on reverse his name, Apollonii Philareti, in a circle, stamped in gold”)

● William & Thomas Boone, London - bought in sale (£13 10s)

● Henri-Eugène-Philippe-Louis d’Orléans, duc d’Aumale (1822-1897) (opac “duc d’Aumale (acq. vente Cage, juin 1867)”)

● Léopold Delisle, Chantilly. Le Cabinet des livres. Imprimés antérieurs au milieu du XVIe siècle (Paris 1905), no. 1869 (“Reliure au nom du possesseur: Apol | lonii Phila | reti, et au médaillon de l’aigle planant dans les airs au-dessus d’une mer sur laquelle nagent des poissons, avec la légende: Este Procvl”)

● Chantilly, Musée Condé, XXII-BIS-B-003 (opac “Reliure italienne, 16e siècle, maroquin brun, décor de filets et fers pleins dorés, armes et devise du secrétaire de Paul III, tranches dorées”)

literature

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.118 no. 8 & Pl. 56

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 824

Lanckorońska, op. cit., pp.300-307 Fig. 4

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.92 no. 7

(8) Thucydides, Thoukydidis. Thucydides [Greek] (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, May 1502)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● unidentified owner, inscription “Fr. Dom(ini)cus Rubeus Bonon(ien)sis” (17C)

● unidentified owner, inscription “Sauterive” (Dauterive?) (18C)

● Louis-Alexandre Barbet (1850-1931)

● Henri Baudoin, Maurice Ader & Librairie Giraud-Badin, Catalogue de la Bibliothèque de feu M. L.-A. Barbet. Première partie, Paris, 13-14 June 1932, lot 148

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 26,100)

● Cortlandt Field Bishop (1870-1935); Shirley Douglas Falcke (1889-1957)

● Kende Galleries at Gimbel Brothers, The magnificent French library formed by the late Cortlandt F. Bishop; the property of Mr. and Mrs. Shirley Falcke, Lenox, Massachusetts, New York, 7-8 December 1948, lot 316 (“This binding is completely unrestored. The bottom of the backstrip is chipped with loss of half of the bottom panel: several wormholes have perforated and loosened the top compartment of the spine and the very top of the back hinge: diagonal cut on the front cover: water has discoloured about a third of the back cover and has left marks throughout the second half of the volume. Margins of the last five leaves frayed, and tear in one leaf”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($290)

● Albert-Louis Natural (1918-2002)

● Librairie Quentin, Molènes, Geneva; their Catalogue 7 (Geneva 1985), item 99 (CHF 56,000; “l’un des 13 Filareto”)

● Otto Schäfer (1912-2000), acquired in 1985 (OS 1314) (Von Arnim)

● Otto-Schäfer-Stiftung e.V., Schweinfurt

● Sotheby’s, The collection of Otto Schäfer. Part I: Italian books, sold by order of the Dr. Otto-Schafer-Stiftung e.V., New York, 8 December 1994, lot 181

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased in the above sale via Martin Breslauer Inc.) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0069]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, The Aldine Collection: N-Z, New York, 25 June 2025, lot 1497 ($317,500) [RBH N11571-1497]

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 825 & Pl. 132

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.92 no. 8

Manfred von Arnim, Europaïsche Einbandkunst aus sechs Jahrhunderten: Beispiele aus der Bibliothek Otto Schäfer (Schweinfurt 1992), no. 30

(9) Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius, L. Coelii Lactantii Firmiani Diuinarum institutionum libri septem proxime castigati, et aucti (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Andrea Torresano, March 1535)

Bound in Northern Italy

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Carlo Lochis (1843-1899)

● Nicolas Rauch, Catalogue 1: Catalogue de très beaux livres (Mies, Vaud [Switzerland] 1948), item 43 (CHF 5500)

● Raphaël Esmerian (1903-1976)

● E. & A. Ader, J.-L. Picard, J. Tajan & Claude Guérin with Georges Blaizot, Bibliothèque Raphaël Esmerian, première partie: Manuscrits à peintures, livres des XVe et XVIe siècles, Paris, 6 June 1972, lot 83

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (FF 43,000)

literature

Achille Bertarelli & David-Henry Prior, Gli exlibris italiani (Milan 1902) p.19 (illustrated; “Legatura di un Lattanzio appartenuto ad Apollonio Filarete. (Gentile comunicazione del fu Conte Carlo Lochis”) [link]

Giuseppe Fumagalli, Di Demetrio Canevari, medico e bibliofilo genovese, e delle preziose legature che si dicono a lui appartenute (Florence 1903), pp.11-12

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.117 no. 4

Dorothy Miner, The History of bookbinding 525-1950 A.D. (Baltimore 1957), no. 228 (“Mr Raphael Esmerian”)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 819 & Pl. 133

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.93 no. 9

(10) Ambrosius Aurelius Theodosius Macrobius, Macrobii Ambrosii Avrelii Theodosii, viri consvlaris, & illustris, in somnium Scipionis, Lib. II. Saturnaliorum, Lib. VII. Ex varijs, ac vetustissimis codicibus recogniti, & aucti (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1542)

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● probably Convento di S. Giovanni in Canale, Piacenza (Dominicans) (opac “The bottom of the title-page has been removed and later repaired”)

● Don Diego Cristiano Antonio Francesco Pignatelli (1855-1938), exlibris

● John Walter Hely-Hutchinson (1882-1955), Chippenham Lodge, Ely, donation label dated 8 December 1947

● Eton, Eton College Library, Sa1.4.08 (opac “The bottom of the title-page has been removed and later repaired”; “Book-label of John Hely-Hutchinson of, dated 1947”; “16th century brown morocco; gold tooled; three raised bands; on back board: “Apolloni Philareti”; in green box.”)

literature

Mostra storica della legatura artistica in Palazzo Pitti (Florence 1922), no. 298 (“S.E. il Principe Diego Pignatelli d’Angiò, Roma”)

Filippo Rossi, “Le Legature italiane del 500” in Dedalo: Rassegna d’arte, Anno 3 (1922-1923), pp.373-396 (p.386, illustrated; “Roma, Propr. Del Principe Pignatelli d’Angio”)

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.118 no. 5

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 820 & Pl. 134

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.93 no. 10

(11) Pietro Vettori, Explicationes suarum in Catonem, Varronem, Columellam Castigationum (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1542), bound with: Giorgio Merula, Enarrationes vocum priscarum in libris de re rustica (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1541)

Bound in Northern Italy

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Convento di S. Giovanni in Canale, Piacenza (Dominicans), inscription “Vendu par le religieux du Couvent de Placence” [Nixon]

● Girolamo, marchese d’Adda Salvaterra (1815-1881) (Davies, stating “notes by Marquis d’Adda inserted in volume” and “exlibris Marquis d’Adda”; as Foot does not mention D’Adda, his exlibris and notes apparently have been removed)

● Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919) but [not traced in the Catalogo dei libri posseduti da Charles Fairfax Murray provenienti dalla Biblioteca del marchese Girolamo d’Adda (London [i.e. Florence] 1902)]

● Madame E. Rahir (G. Hobson)

● Arthur Rau, Paris

● Henry Davis (1897-1977), purchased 1949

● London, British Library, Henry Davis Gift 797

literature

Charles Fairfax Murray, A list of printed books in the library of Charles Fairfax Murray ([London?] 1907), p.237 (“olive morocco, with medallion in gold, within a border on front cover, and inscription ‘Apollonii Philareti,’ within similar border on back cover”)

Hugh W. Davies, Catalogue of a collection of early French books in the library of C. Fairfax Murray (London 1910), no. 567 (“ex libris Marquis d’Adda”; illustrated)

G. Hobson, op. cit., pp.118-119 no. 9

Exposition du livre italien, op. cit., no. 938 (“Collection particulière”)

The Italian book 1465-1900: Catalogue of an exhibition held at the National Book League and the Italian Institute (London 1953), no. 268 (“Lent by Henry Davis”)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 826

A. Hobson, p.93 no. 11

Mirjam Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: A Collection of bookbindings, volume 3: A Catalogue of South-European bindings (London 2010), no. 313

(12) Giovanni Della Casa, Ms “De potentium et tenuium inter se officiis”

Bound by Marcantonio Guillery

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Urb lat. 931 [image, link]

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 817 & Pl. 134

Nixon, op. cit., p.30 (“it is not quite certain that [De Marinis] no. 817, the binding removed from a manuscript of Giovanni della Casa … actually belonged to him”)

A. Hobson, op. cit., p.94 no. 12 (“Although Filareto’s name has been excised from 12, there is no reason to doubt his ownership”)

(13) Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geographicae enarrationis, libri octo. Ex Bilibaldi Pirckeymheri tralatione, sed ad Graeca et prisca exemplaria a Michaële Villanovano secundo recogniti (Lyon: Gaspar Trechsel for Hugues de La Porte, 1541)

Bound by Marcantonio Guillery

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone, Count Libri (Libri-Carrucci) (1803-1869)

● S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson, Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri, London, 1-15 August 1859, lot 2177 (“ruled, in the original brown morocco, gilt edges, the sides covered with gold ornaments, elegantly tooled in compartments. In the centre of the obverse side of cover is, stamped in gold, a medallion, in which are represented ‘an Eagle soaring towards the sky, Rocks, and Fish swimming in the Sea,’ surrounded by the motto ‘PROCUL ESTE.’ At the top of the same side stands in gold letters ‘cosmographia ptolemaei.’ In the centre of the reverse, in letters of gold, will be found ‘applonii philareti.’.”)

● William & Thomas Boone, London - bought in sale (£20 10s) [Boone was Slade’s usual agent]

● Felix Joseph Slade (1788-1868)

● Felix Slade, bequest to the British Museum, 1868

● London, British Library, C.37.1.4

literature

A catalogue of the antiquities and works of art exhibited at Ironmongers’ Hall, London, in the month of May, 1861 (London 1869), I, “Books and Book-Bindings, in the Collection of Felix Slade, Esquire”, pp.298-304 (p.302) [link]

Catalog of the library of Felix Slade [manuscript, in Grolier Club], England, ca 1866, fol. 104 (annotated “British Museum”)

Edward Edwards,Lives of the founders of the British Museum with notices of its chief augmentors and other benefactors, 1570-1870 (London 1870), II p.716 [link]

Catalogue of the Collection of Glass formed by Felix Slade … And an Appendix containing a description of other works of art presented or bequeathed by Mr Slade to the nation (London 1871), p.174 no. 84]

W.Y. Fletcher, Foreign bookbindings in the British Museum (London 1896), Pl. 21 (“Bequeathed by Felix Slade, Esq.”)

G. Hobson, op. cit., p.118 no. 6 & Pl. 55

British Museum, A guide to the exhibition in the King’s library illustrating the history of printing, music-printing and bookbinding (London 1939), p.136 no. 5

Helwig,op. cit., I, p.175 Fig. 55

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 822

A. Hobson, op. cit., p. 94 no. 13

(14) Empty binding, possibly once containing the second part of Iamblichus, De mysteriis Aegyptiorum (Venice: Aldo Manuzio, 1497)

Bound by Marcantonio Guillery

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● “found in an Italian library by Mario Witt of the Libreria Leo Olschki” (Christie’s)

● Patrick King, Stony Stratford; their Catalogue 12: Fifty rare books (Stony Stratford 1982), item 22 (illustrated on cover; “Sold”)

● Michel Wittock (1936-2020)

● Christie Manson & Woods, The Michel Wittock collection. Part I, Important Renaissance bookbindings, London, 7 July 2004, lot 60 [RBH 6996-60]

● unsold

literature

Cinq siècles d’ornements dans le décor extérieur du livre 1515-1983 (Brussels 1983), no. 4

Anthony Hobson & Paul Culot, Italian and French 16th century bookbindings (Brussels 1991), pp.18-21 no. 4

Macchi, op. cit., pp.150-151 Tav. 55 (“Legatura vuota continente probabilmente in origine la seconda parte di Iamblichus, De Mysteriis Aegyptiorum, Venezia, Aldus, 1479”)

additions to hobson

(15) Publius Ovidius Naso, Quae hoc volumine continentur. Annotationes in omnia Ouidij opera. Index fabularum et caeterorum, quae insunt hoc libro secundum ordinem alphabeti. Ouidii metamorphoseon libri XV [part I only] (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, 1533)

Bound in Northern Italy

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Bergamo, Biblioteca Civica Angelo Mai, Cinq. 1 666

literature

Federico Macchi, Legature storiche nella Biblioteca “A. Mai” (“Marocchino marrone decorato a secco ed in oro. Fasci di filetti delimitano una cornice dorata a due filetti, quest’ultima provvista di archi. In testa la scritta “OVIDI METAM”. Al centro dei piatti, il “supra libros” di Apollonio Filareto con il motto “ESTE PROCUL” (70x50 mm.). Gigli e fregi a mensola accantonati. Sul piatto posteriore, la cartella quasi totalmente scomparsa (è tuttora leggibile “(APOL)L/(LON)II/(PHIL)A”.), è stata sostituita con un lembo di cuoio bruno, decorato con alcuni punzoni circolari (35 mm. di diametro) sovrapposti. Tracce di quattro bindelle in tessuto verde. Taglio dorato e cesellato con motivi a cordami. Dorso a nervi alternati a mezzi nervi decorati con filetti dorati obliqui, provvisti di una stella al centro dei compartimenti. Carte di guardia bianche, prive di filigrana. Capitelli gialli e verdi. Labbri decorati con serie di tre filetti obliqui.” [link])

(16) Judah Abravanel (Leone Ebreo), Dialogi di amore, composti per Leone medico, di natione hebreo, et dipoi fatto christiano (Venice: Sons of Aldo Manuzio, 1541)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● unidentified owner, inscription “flaminii rimnialis” (?) on title-page (16C)

● Arthur Lauria, Paris

● Maurice Burrus (1882-1959), his acquisition label dated 1938

● Thierry de Maigret & Emmanuel de Broglie, Livres et manuscrits, Paris, 27 November 2013, lot 166 (€98,000)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased in the above sale, 1997) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0431; offered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library: The Aldine Collection, A–C, New York, 12 October 2023, lot 92]

literature

Unrecorded

(17) Francesco Petrarca, Il Petrarca (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio & Heirs of Andrea Torresano, June 1533)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese

provenance

● Apollonio Filareto (ca 1505-1569), supralibros, his impresa on upper cover, his name lettered on lower cover

● Tommaso Gelli (1835-1917), exlibris, lawyer of Pistoia [Bragaglia no. 2270]

● Martel Maides Auctions, Autumn 2023 Fine Art, Antiques & Jewellery, St. Peter Port, Guernsey, 20 September 2023, lot 257 (“contemp. Venetian binding, tooled in gilt, the central oval armorial within a panel of leafy scrolls and spandrels, the name 'Petrarca' above, the conforming back with central oval motto ‘Apollonii Philareti’, later rebacking and corners”; lacking title-page)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (£2000)

● Guido Bortolani, Modena

literature

Unrecorded