Ippolito d’Este’s Library

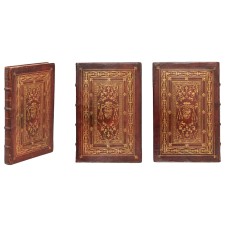

Details from nos. 5 (left) and 2 (right)

As one of the wealthiest cardinals of the time, a voracious collector of antiquities and works of art of all kinds, and from a family with a strong tradition of bibliophily, Ippolito presumably accumulated a great number of books. The ongoing investigation of his Libri di Guardaroba which has uncovered so far three book lists and deepened our knowledge of the Cardinal’s bibliophilic interests, does not yet allow an estimate of the total number of books in his possession. When the guardaroba maggiore recorded the Cardinal’s property in 1548, prior to his return to Italy after fifteen years at the French court, 100 books and manuscripts were counted.2 Around 98 were listed when an inventory was made in 1550,3 and between 150-200 volumes when one was taken at Tivoli in 1555.4 Approximately 165 volumes are summarily mentioned in a post-mortem list of the Cardinal’s property in one of his Roman palaces.5 Four of the seven known volumes relate to entries in these book lists.

Ippolito had received from Fulvio Pellegrino Morato and Celio Calcagnini a traditional humanist education, and was raised to appreciate art and music. His book lists depict a literary taste favouring the works of classical authors in the original Greek or Latin. Among authors represented are Aesopus, Appianos, Aristoteles, Aulus Gellius, Gaius Iulius Caesar, Gaius Valerius Catullus, Marcus Tullius Cicero, Ioustinou, Titus Livius, Titus Lucretius Carus, Martialis, Modestus, Publius Ovidius Naso, Gaius Plinius Secundus, Plato, Titus Maccius Plautus, Gaius Sallustius Crispus, Publius Papinius Statius, Thucydides, Valerius Maximus, Publius Vergilius Maro, and Xenophon. An interest in archaeology is reflected by Fabio Calvo’s Antiquae Urbis Romae cum Regionibus Simulacrum, and two albums of drawings, “un libro con li dissegni delle antiquità di Roma del Marcanova, coperto di veluto turchino” and “uno libro di anticalie di Roma coperto di velluto morello”.

An enthusiasm for astronomy and instruments is suggested by two volumes of Claudius Ptolemaeus (his Geographia, in Greek, and another); two of Luca Gaurico (his Ephemerides, and another); two of Sebastian Münster (Organum uranicum; Horologiographia); four of Oronce Finé (Quadrans astrolabicus, bound with In sex priores libros geometricorum elementorum Euclidis demonstrationes; De arithmetica practica; Protomathesis); one of Johannes de Sacrobosco (La sfera); and one of Georg von Peurbach (Theoricae novae planetarum). Among his collection of maps is “La descriptione del mondo in carta pecora scritta a mano miniata” by the Dieppe cartographer Pierre Desceliers, dated 1543.

Ippolito owned the Libro della arte della Guerra and Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio of Niccolò Machiavelli, also several of Paolo Giovio’s histories, including La vita di Alfonso da Este of which he was the dedicatee; the histories of France by Paulus Aemilius Veronensis, Robert Gaguin, Symphorien Champier, and Philippe de Commines; Konrad Peutinger’s De mirandis Germaniae antiquitatibus; and Aegidius Tschudi’s De prisca ac vera alpina Rhaetia. He had a copies of Boccaccio’s De genealogia deorum gentilium and Petrarca’s Trionfi e canzoniere; Ariosto’s Orlando furioso printed on vellum and bound in crimson velvet, and a French translation of that work bound in red leather; unspecified “Novelle francese” bound in black leather; Giovanni Gioviano Pontano’s Carminum in red leather, and Gigio Artemio Giancarli’s La capraria. comedia also in red leather, but “con oro” (Ippolito was the dedicatee). His copy of Juan de Flore’s Historia di Aurelio e Isabella was unbound (sciolto). Ippolito possessed several works on the “art of love”, by Giuseppe Betussi (Il Raverta), Sperone Speroni (Dialogo), Leon Battista Alberti (Hecatomphila), and Alessandro Piccolomini (De la institutione di tutta la vita de l’huomo nato nobile; Dialogo della bella creanza de le donne). He was passionate about hunting and possessed both a printed edition and a manuscript of Gaston Phébus’s Livre de la Chasse.

Apart from liturgical and devotional books, of which many are itemised in the book lists, Ippolito owned personally few theological works. Notable among them are Guillaume Budé’s De transitu Hellenismi ad christianismum, Berthold Pürstinger’s anticlerical Onus ecclesiae, Claude de Seyssel’s Adversus errores et sectam Valdensium disputationes, a pamphlet advising priests on how to deal gently with the Waldensian heresy, and a manuscript “Dialoghi del Virgerio”, this last assumed to be a tract of the convicted heretic Pier Paolo Vergerio.6 Ippolito’s exposure to heterodox ideas is further evidenced by lavishly-bound copies of Erasmus’s Paraphrases of the four Gospels and Acts of the Apostles, Erasmus’s Annotations on Paul’s Epistles to the Galatians and Ephesians, and Novem Testamentum, and by “La Bibia in volume grande da messa, coperto di veluto verde” - perhaps one of the Venetian editions of Antonio Brucioli’s Italian translation, of which the Cardinal was the dedicatee.7 When in the 1559 the Cardinal became briefly of interest to the Inquisition, the works of Erasmus, the Bible, Machiavelli’s Discorsi and some other books (about 15 in total) were removed from his library at the Villa d’Este.8

Unmentioned in the available book lists are many publications dedicated to Cardinal Ippolito, some written by courtiers, namely Pirro Ligorio’s Libro delle Antichità di Roma (1553) and Vita di Virbio (1569), Marc Antoine Muret’s Variae lectiones (1559), and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina’s first two volumes of motetti (1569, 1572), others written in gratitude or in anticipation of patronage, such as Federico Grisone’s Gli ordini di caualcare (Naples 1550; reprinted 1558, 1559), Nicola Vicentino’s L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (1555), Daniele Barbaro’s Italian translation of Vitruvius (1556), and Enea Vico’s Le imagini delle donne auguste (1557). It is inconceivable that Ippolito was not gifted these books by their authors. It is improbable too that Ippolito should have made two stamps of his armorial insignia, then employ them on so few volumes. He surely possessed more books than those recorded in these lists, but what has become of them? Apart from the Ariosto, which was absorbed at an unknown date into the private library of the Barberini family at Rome, and the Bembo, which was in Ferrara in the early 18th century, the seven surviving volumes provide no clue as to when and how Ippolito’s library was dispersed.

1. Giuseppe Fumagalli, L’arte della legatura alla corte degli Estensi, a Ferrara e a Modena, dal sec. XV al XIX: col catalogo delle legature pregevoli della Biblioteca Estense di Modena (Florence 1913), p.21 (“Del card. Luigi d’Este questo e il solo volume posseduto dalla Biblioteca: e nessuno ne ho trovato dei due cardinali Ippolito, nè credo se ne conoscano altrove.”)

2. Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione dei Principi, 888, c. 164v: “Libri grandi e picolli legati a diversi modi et de più perfessione, utelli et inutilli, a stampa et a pena numero cento”. Carmelo Occhipinti, “Il ‘Camerino’ e la ‘galleria’ nella Villa d’Este a Fontainebleau (‘Hôtel de Ferrare’) in Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia Serie IV, 2 (1997), pp.601-635 (p.607); Carmelo Occhipinti, Carteggio d’arte degli ambasciatori estensi in Francia (1536-1553) (Pisa 2001), pp.308-313 (p.311).

3. Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione della Casa, Guardaroba, Registri, 169, cc. 28v-31v. Transcription by Occhipinti, op. cit. 2001, pp.316-320; cf. Occhipinti, op. cit., 1997, p.607. This list, made by Antonio Sala in 1550, itemises books and describes their bindings.

4. Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione Principi, 928, c. 156v: “Un conto de libri de più e diverse sorte a stampa et a pena de’ dare la infrascrita quantità e qualità de libri, qualli sono in guardarobba”. The entries consist of the name of the author or the title of the work, with languages and subjects intermingled; bindings are described. Transcriptions by Vincenzo Pacifici, Ippolito II d’Este: cardinale di Ferrara (Tivoli [1920]), p.374-376; Occhipinti, op. cit. 2001, pp.327-331; Maria Luisa Angrisani, “Cultura rinascimentale di Ippolito d’Este: la ‘libraria’” in Atti e Memorie della Società Tiburtina di Storia e d’Arte 82 (2009), pp.111-133 (pp.118-120).

5. Rome, Archivio di Stato, Notai del tribunale dell’auditor Camerae, notaio Fausto Pirolo, vol. 6039, cc. 450-489v: “Inventarium bororum mobilium bonae [memoriae] Cardinalis Ferrariensis in palatio in Montegiordano [2 December 1572]” (c.478v: “Libri di più sorte centoquarantadoi. / Un messale miniato coperto di velluto cremesino. / Un libro da desegni coperto di carta pecora. / Sedici volumi di cose da messa scritti a penna. / Tre volumi sciolti. / Doi breviari et un messale vecchi antichi.”). Transcription by Carmelo Occhipinti, Collezionismo estense, Fondazione Memofonte [online, link]. A post-mortem inventory taken by the same notary of the Cardinal’s property at the Villa d’Este does not mention books: vol. 6039, cc. 356r-387r: “Possesso et inventario de’ beni della felice memoria dell’illustrissimo e reverendissimo signor cardinal Ferrara trovati in Tivoli [3-4 December 1572]”; see the transcription by Roberto Borgia, “Inventario dei beni del cardinale Ippolito II d’Este trovati nel Palazzo e Giardino di Tivoli (3-4 dicembre 1572)” in Annali del Liceo Classico Amedeo di Savoia di Tivoli, anno XXI, no. 21 (April 2008), pp.39-80. No books were found among the Cardinal’s possessions in the Palazzo Montecavallo: vol. 6039, cc. 344r-355r: “Inventarium bonorum bonae memoriae Hippoliti Estensis Cardinalis de Ferrara. Item in Montecaballo et aliis domibus”); see the transcription by Carmelo Occhipinti, Collezionismo estense, Fondazione Memofonte [online, link].

6. Giulia Vidori, The Path of Pleasantness: Ippolito II d’Este Between Ferrara, France and Rome (Florence 2020), pp.24-25.

7. Guardaroba inventory taken by Antonio Sala, 1550: Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione della Casa, Guardaroba, Registri, 169, cc.28v-29r: “In Acta Apostolorum paraphresis. In Evangelium Ma[r]ci paraphresis. In Novum testamentum paraphresis tomus primus. In orationes, epistules apostolicas paraphresis tomus secundus. In Evangelium Ioannis paraphresis. In Evangelium Lucae - Di Erasmo, coperti tutti sei di corame turchino lavorato d’oro”, “Il Testamento nuovo tradotto da Erasmo, coperto di velluto d’oro con li seragli fatti a S d’oro massiccio, smaltato di nero” (transcriptions by Occhipinti, op. cit. 2001, pp.316-317).

8. See Pacifici, op. cit., pp.374-376; Occhipinti, op. cit. 2001, pp.327-331 (“Conto contrascritto debbe avere a di primo de ottobre 1559 li infrascritti libri li qualli se sono datti allo inquisitore della Minerba nel tempo di papa Paulo quarto”); Angrisani, op. cit., pp.120-124.

list

(1) Ludovico Ariosto, [Orlando furioso di messer Ludouico Ariosto nobile ferrarese nuouamente da lui proprio corretto e d’altri canti nuoui ampliato con gratie e priuilegii] (Ferrara: Francesco Rossi, 1 October 1532)

provenance

● Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), his arms as cardinal illuminated on a frontispiece [i.e. after 20 December 1538] replacing the printed title [compare link and link]

● Guardaroba inventory taken by Antonio Sala, 1550: Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione della Casa, Guardaroba, Registri, 169, c.28v: “Orlando furioso di messer Ludovico Ariosto stampato in carta pecora, coperto di velluto carmesino rosso” (transcription by Carmelo Occhipinti, Carteggio d’arte degli ambasciatori estensi in Francia (1536-1553) (Pisa 2001), p.317)

● Guardaroba inventory taken at Tivoli, 1555 (“Conto de’ libri a stampa et a penna qualli sono in guardarobba”): Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione Principi, 928, c. 157: “Orlando furioso in carta pecora coperto di veluto cremisino” (transcriptions by Vincenzo Pacifici, Ippolito II d’Este: cardinale di Ferrara (Tivoli [1920]), p.376; Occhipinti, op. cit. 2001, p.327)

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Barb. Lat. 3942 (opac [link]; image, [source])

literature

Conor Fahy, “Some observations on the 1532 edition of Ludovico Ariosto’s ‘Orlando Furioso’” in Studies in Bibliography 40 (1987), pp.72-85 (p.80, p.85 no. 11)

C. Fahy, “More on the 1532 edition of Ariosto’s ‘Orlando Furioso’” in Studies in Bibliography 41 (1988), pp.225-232

C. Fahy, L’Orlando Furioso del 1532: Profilo di una edizione (Milan 1989), p.22 no. 5

(2) Pietro Bembo, Petri Bembi Epistolarum Leonis decimi pontificis max. nomine scriptarum libri sexdecim ad Paulum tertium pont. max. Romam missi (Venice: Giovanni Padovano & Venturino Ruffinelli, [1535?])

provenance

● Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), armorial supralibros with cardinalitial insignia [created Cardinal by Paul III, 20 December 1538]

● possibly Guardaroba inventory taken at Tivoli, 1555 (“Conto de’ libri a stampa et a penna qualli sono in guardarobba”): Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione Principi, 928, c. 157: “Epistole di Bembo” (transcribed by Vincenzo Pacifici, Ippolito II d’Este: cardinale di Ferrara (Tivoli [1920]), p.376) [inventory entry otherwise might record the Italian translation of Bembo’s Lettere, 1548]

● Girolamo Baruffaldi (1675-1755), inscription “Hieronimo Baruffaldi” on endleaf

● unidentified owner, supralibros, initials “B.R.B.” stamped on spine

● unidentified owner, blue oval inkstamp “cL” (?) on upper pastedown (19C)

● Luigi Lubrano, Naples; their Bollettino del Bibliofilo: Notizie, illustrazioni di libri a stampa e manoscritti 2 (1920), pp.80-81 item 41 [illustrated; arms not identified]; Bollettino del Bibliofilo 3 (1921), “Supplemento al volume terzo del Bollettino del bibliofilo: Libri antichi e rari … in vendita a prezzi netti … 1921”, p.7 item 53 (Lire 2000; “Legatura originale di marocchino rosso con fregi dorati ai piatti, alle armi di Ippolito II d’Este …” & illustration p.8: “Bembus 1535 alle angrisani. Formato originale mm. 0,310 x 0,210)

● E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., London [E.P. Goldschmidt & Co. stockbook, in Grolier Club Library, #1517, entered with code “B 1517” (Lubrano not named as source)]; their Catalogue 2: Rare and valuable books (London 1923), item 140 (£27 10s; “on fly-leaf the autograph of Hieronimo Baruffaldi, the Italian poet, who lived at Ferrara and died 1735 [sic]. Similar sumptuous Este-bindings are reproduced in Fumagalli, Arte della Legatura alla Corte degli Estensi, 1913”)

● Joseph Baer & Co., Frankfurt am Main [Goldschmidt stockbook, as sold to Baer on 4 May 1925]

● Jean Fürstenberg (1890-1982), exlibris

● Martin Breslauer Inc., New York; their Catalogue 104/II: Fine books in fine bindings from the fourteenth to the present century (New York 1981), item 158 ($7800); Catalogue 107: Italy, Part II: Books printed 1501 to c. 1840 (New York [1984]), item 40 ($7800)

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 1989) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #2081]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 9 [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($30,480) [RBH N11245-9]

literature

Exposition de reliures de la Renaissance: collection Jean Furstenberg: 30 September 1961 (Paris 1961), no. 11

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 633 (“Napoli. Libreria Lubrano (1920) … Marr. rosso, dec. dorata: cornice come sopra [i.e. Pl. 115, a Roman binding], vari gigli; armi del cardinale Ippolito d’Este (creato nel 1534, morto nel 1572)”)

Tammaro De Marinis, Die italienischen Renaissance-Einbände der Bibliothek Fürstenberg (Hamburg 1966), pp.52-53

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Collection Jean Furstenberg: 3 mai-5 juin 1966 (Geneva 1966), no. 10

Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: An enquiry into the formation and dispersal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), p.84 (“List C: Bindings by Niccolò Franzese” no. 72 “With open-leaf tools … With the continuous interlaced border and the arms of Cardinal Ippolito d’Este. Fürstenberg 52”)

(3) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Le epistole famigliari di Cicerone (?) [when offered in 2024 by Wannenes, the text was identified as “Le epistole famigliari di Cicerone. Venezia: Aldo Manuzio eredi, 1549” in octavo format, “mancano frontespizio e colophon”. Aong the images on the auctioneer’s website, however, is the colophon leaf (x3 recto) of the 1549 Aldine Epistolae ad Atticum (CNCE 12279). According to De Marinis, op. cit., no. 922, the edition is “Venezia, Aldo, 1546, in-4°”; however, no edition of 1546 is recorded by Edit 16, just two editions both dated 1545, and both in octavo format: CNCE 12264 (link), CNCE 12265 (link). Hobson identifies De Marinis no. 922 as “Cicero, Ad Atticum. Venice 1549”]

provenance

● Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), armorial supralibros with cardinalitial insignia [created Cardinal by Paul III, 20 December 1538]

● possibly Guardaroba inventory taken by Antonio Sala, 1550: Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione della Casa, Guardaroba, Registri, 169, c.29v: “L’epistole famigliare di Cicerone in stampa d’Aldo coperti di corrame con fili d’oro” or c.30v: “Epistole familiari di Cicerone, coperte similmente [i.e. bound in “corame pavonazzo”] (transcriptions by Carmelo Occhipinti, Carteggio d’arte degli ambasciatori estensi in Francia (1536-1553) (Pisa 2001), pp.317, 319)

● Orazio Sanminiatelli (1894-1972)

● Wannenes, Auction 543: Libri e manoscritti, Milan, 19 December 2024, lot 12 (“Rara legatura alle armi del cardinale Ippolito II d’Este, una delle poche conosciute alla letteratura, la presente citata da De Marinis e Hobson. … La legatura è nello stile del legatore romano Niccolo Franzese…” [link])

literature

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 922 (“Perignano (Pisa), raccolta del conte Orazio Sanminiatelli … Marr. rosso, cornice come sopra [Pl. 156, a Roman binding], con lo stemma del cardinale Ippolito II d’Este”)

Hobson, Apollo & Pegasus, op. cit., p.86 no. 92 (“With [Niccolò Franzese’s] interlaced border tool …Perignano, the late Count Sanminiatelli. Arms of Cardinal Ippolito d’Este”)

(4) Marcus Tullius Cicero, Rhetoricorum ad C. Herennium libri IIII incerto auctore. Ciceronis De inuentione libri II. De oratore, ad Q. fratrem libri III. Brutus, siue, De claris oratoribus, liber I. Orator ad Brutum, Topica ad Trebatium, Oratoriae partitiones, initium libri De optimo genere oratorum. Corrigente Paulo Manutio Aldi filio (Venice: Heirs of Aldo Manuzio, September 1546)

provenance

● Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), armorial supralibros with cardinalitial insignia [created Cardinal by Paul III, 20 December 1538]

● possibly Guardaroba inventory taken at Tivoli, 1555 (“Conto de’ libri a stampa et a penna qualli sono in guardarobba”): Modena, Archivio di Stato, Camera Ducale, Amministrazione Principi, 928, c. 160v: “Rettorica di Cicerone in ottavo” (transcriptions by Vincenzo Pacifici, Ippolito II d’Este: cardinale di Ferrara (Tivoli [1920]), p.376; Occhipinti, op. cit. 2001, p.331)

● Carlo Rovelli, O.P., Bishop of Como (1740-1819) (Montecchi)

● Milan, Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, AO.X.37

literature

Tomaso Gnoli, Catalogo descrittivo della mostra bibliografica : manoscritti e libri miniati, libri a stampa rari e figurati dei secc. XV-XVI, legature artistiche, autografi ([Milan 1929]), no. 136

Giorgio Montecchi, Le edizioni Aldine della Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense di Milano (Milan 1995), p.136 (“AO.X.37 ha legatura in pelle con impressioni in oro e stemma cardinalizio sui piatti … Sul r. della 1 c. di guardia anteriore dell’esemplare in AO.X.37 nota ms.: Fr. Caroli Rovelli Ord. Praed.”)

Federico Macchi, Arte della legatura a Brera: Storie di libri e biblioteche: secoli XV e XVI (Cremona 2002), no. 49 [compare, link; link]

Federico Macchi, Arte della legatura a Brera: Storie di libri e biblioteche Il Barocco, p.38 [link]

(5) Bartolomej Georgijević, Opera noua che comprende quattro libretti: si come nel sequente foglio leggendo, meglio si potrà intendere. Bartholomeo Georgieuitz de Croacia, detto Pellegrino Hierosolymitano authore (Rome: Antonio Barré, 1555)

provenance

● Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), armorial supralibros with cardinalitial insignia [created Cardinal by Paul III, 20 December 1538]

● William Beckford (1760-1844)

● Alexander Douglas, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767-1852)

● Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the second portion of the Beckford Library, removed from Hamilton Palace, London, 11-22 December 1882, lot 108 (“presentation copy … with Cardinal’s arms and inscription in gold letters on sides, ‘Illustriss. Principi et Reverendissimo D. Hippolito Card. Ferr. Author, D.D.’, gilt gaufred edges”)

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£13)

● Joannes Gennadius (1844-1932)

● Athens, Gennadius Library, B/TH 4/G 361 (opac Brown calf, with cardinal’s arms on sides, and inscription: illustriss. principi. et reverendissimo. hippolito card. ferr. author. d.d. … From Beckford sale, 1880)

literature

Lucy Allen Paton, Selected bindings from the Gennadius library (Cambridge 1924), p.23 & Pl. 21

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 923 bis (“Marr. castano, dec. dor.: cornice di edera con gigli agli angoli; sul piatto anteriore armi del cardinale Ippolito d’Este colla leggenda Illustriss. / Principi / Et Reveren / Dissimo / D. / ; sul posteriore Hippolito / Card. Ferr. / Avthor / .D.D. / .”)

(6) Bartolomeo Ricci, Bartholomaei Riccii Lugiensis Epistolarum familiarium libri VIII (Bologna: [s.n.], 1560)

provenance

● Bartolomeo Ricci (1490-1569), supralibros, barth. riccivs. d.d. lettered on lower cover, gifted to

● Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), supralibros, inscription hippol. atestio. cardinall. ampliss. lettered on upper cover [created Cardinal by Paul III, 20 December 1538]

● E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., London (from E.P.G’s private collection, taken into stock 1 October 1923; E.P. Goldschmidt & Co., Stock Books 1921-1981, #1341, in Grolier Club Library [link]) [Goldschmidt Stock Books, op. cit, undated sale to Putti]

● Vittorio Putti (1880-1940)

● possibly Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, E 067 E 027 [link]

literature

E.P. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance bookbindings exemplified and illustrated from the author’s collection (London 1928), no. 228 & Pl. 90 (“Dark olive morocco. In the centre of the front cover the impression in silver of a graceful cartouche with the lettering in Roman capitals, Hippol. | Atestio. | Cardinall. (sic) | Ampliss., surrounded with a frame of six fillets, four blind stamped and two impressed in silver; in each of the angles a typical ‘Aldine leaf’. The back cover bears the same ornamentation, and the inscription within the cartouche reads Barth. | Riccivs. | D.D.”)

(7) Innocenzio Ringhieri, Cento giuochi liberali, et d’ingegno, nouellamente da m. Innocentio Ringhieri gentilhuomo bolognese ritrouati, et in dieci libri descritti (Bologna: Anselmo Giaccarelli, 1551)

provenance

● Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), supralibros, lettered r hipolito estense on covers

● George Spencer-Churchill (1766-1840), Marquess of Blandford and later fifth Duke of Marlborough

● R.H. Evans, White Knights library. Catalogue of that distinguished and celebrated library, containing very fine and rare specimens from the presses of Caxton, Pynson, and Wynkyn De Worde &c … Part II, London, 22 June-3 July 1819, lot 3582 (“ornamented binding in compartments”)

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (£1 5s)

● Richard Heber (1773-1833)

● Sotheby & Son, Bibliotheca Heberiana. Catalogue of the library of the late Richard Heber, Esq. Part the Ninth. Removed from Hodnet Hall, London, 11-26 April 1836, lot 2655 (“fine copy, in old richly ornamented binding in compartments. Liber olim Cardinalis Hippolyti Estensis”)

● Bohn - bought in sale (£1 8s)

● George John Warren, 5th Baron Vernon (1803-1866) (Hobson)

● Robert Stayner Holford (1808-1892)

● Lt Col. Sir George Lindsay Holford (1860-1926)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of extremely choice & valuable books principally from continental presses, and in superb morocco bindings, forming part of the collections removed from Dorchester House, Park Lane, the property of Lt.-Col. Sir George Holford, K.C.V.O. (deceased), London, 5-9 December 1927, lot 707 (“contemporary North Italian binding, vellum, the sides decorated with an elaborate arabesque design stamped in black, lettered in the centre (1) of the upper cover R. Hipolito; (2) of the lower cover Estense (Cardinal Hippolyto of Este); back decorated with small tools in black, gauffred edges; from the White Knights-Heber-Vernon collections … Shown at the Exhibition of Bookbindings held by the First Edition Club in 1926.”)

● Bernard Quaritch, London - bought in sale (£80); their Catalogue 520: A Catalogue of rare and valuable works (London 1936), item 711 (£65; “in a contemporary Italian vellum binding stamped in black to an elaborate arabesque design, with the name of Cardinal Hippolyto d’Este stamped on the sides, R. Hipolito on the upper cover and Estense on the lower, the back decorated with small tools, gauffered edges … This binding was exhibited by the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1891, and was illustrated in their catalogue.”)

● John Roland Abbey (1894-1969)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books and fine bindings from the celebrated collection the property of Major J.R. Abbey, London, 21-23 June 1965, lot 584 & Pl. 64 (“with his name R. Hipolito Estense in the centre of the covers”)

● Jean Hugues, Paris - bought in sale (£480)

● Amsterdam, Universiteits Bibliotheek, OTM Band 1 C 15 [image source]

literature

Burlington Fine Arts Club, Exhibition of bookbindings (London 1891), Case E, p.25 no. 17 & Pl. 26 (“Italian binding of the 16th century; white vellum; elaborately tooled in black. The book formerly belonged to Cardinal Hippolyte d’Este, whose name is stamped upon the covers. R.S. Holford, Esq.”)

Anthony Hobson, French and Italian collectors and their bindings illustrated from examples in the library of J.R. Abbey (Oxford 1953), no. 68

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 1331

Banden Kast Bijzondere Collecties Universiteit van Amsterdam (binding image and details) [link]