Fernando de Torres (1521-1590)

Thirteen bindings executed in Rome in the 1540s and all bearing the initials F.T. are now recorded. Anthony Hobson first drew attention to the collector “F.T.” in 1982, suggesting that he might be the erudite Jesuit theologian Francisco Torres (1509-1584), and listing nine volumes.1 Two more volumes were added to that census in 1996, when Fernando de Torres (1521-1590) was proposed as their owner (no relation of Francisco).2 Another two bindings have subsequently come to light. One of them, a copy of Herodian’s Roman history, in Greek with the Latin translation of Angelo Poliziano (Basel 1543), strengthens the arguments made in 1996 in favour of Fernando de Torres. It is inscribed on an endleaf “Lodovicus de Torres”, no doubt Luis II (Lodovico) de Torres (1533-1584), the younger brother of Fernando. The same inscription “Lodovicus de Torres” is found in a copy of the 1503 Aldine Euripides, which had been bound for Luis I de Torres (1495-1553). Luis II Torres evidently had the use, if not possession, of the family library.

Fernando de Torres (1521-1590) was born in Málaga, one of five sons of Juan de Torres, Comendador de Santiago and Regidor of Málaga (1521-1561), and Catalina de la Vega, granddaughter of the prosperous local merchant Juancho de Haya.3 Apart from the eldest, Diego (ca 1520-1582), who followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming Regidor perpetuo de Málaga, the boys sought advancement through the church: Luis (1533-1584), becoming archbishop of Monreale (1573-1584); Francisco (d. 1568), becoming archdeacon of Vélez-Málaga; Alonso (d. 1596), successively canon, treasurer, and dean of the Cathedral of Málaga.

At an unknown date, Fernando de Torres was sent to Rome, where his uncle, Luis de Torres, held lucrative sinecures in the apostolic chancery. On 23 March 1538, Luis de Torres resigned to Fernando his office of scriptor brevium.4 Fernando is recorded in January 1551, assisting his uncle, now Archbishop of Salerno, in his diocese.5On 26 April 1551, Fernando married Pentesilea Sanguigni (1536-1572), and they welcomed their first (of eleven) children, Luis III de Torres, on 28 October 1551. The building of the Palazzo Torres, initiated by Luis de Torres, was completed around 1560,and Fernando became the first of the family to occupy it. He acquired honours, becoming a Cavaliere di S. Giacomo della Spada, and a Cavaliere dell’Ordine di Malta, and assumed prestigious offices in the municipal administration, serving as caporione for rione S. Eustachio (located between the Piazza Navona and the Pantheon) in 1560, and as conservatore and senatore for rione S. Eustachio in 1566.6 From about 1559, Fernando was the curial agent for Philip II of Spain in the Kingdom of Naples (Regiae Catholicae Majestatis famulo et Agenti in Curia Romana).7 Shortly after his election, Pius V named Fernando secretarius and a papal familiare. When he died in 1590, Fernando was interred in the Cappella de Torres, Santa Caterina dei Funari, Rome, beneath a ledgerstone laid by his son, Luis III.8

The thirteen bindings contain altogether twenty-one works printed between 1524 and 1545, mostly in Latin (one work is in Greek, two in Greek & Latin, and three are in Italian). They were executed in two different shops. Five bindings were produced in a shop which also worked for Luis I de Torres (nos. 3, 6, 10, 13 in the List below), designated by T. Kimball Brooker “F.T.’s First Binder”. A title is lettered within a roundel on the upper cover, and the owner’s initials are similarly situated on the lower cover. All the other bindings were executed in the Roman shop of Niccolò Franzese. They are variously decorated, and some have the initials F.T. on both covers. All the F.T. bindings which retain the original back have a longitudinal gold-tooled spine title.

1. Anthony Hobson, “Who was F.T.?” in Philobiblon 36 (Heft 2, June 1982), pp.166-176. Hobson argues here that the bindings were Venetian; he subsequently returned them to Rome: Anthony Hobson, “Some sixteenth-century buyers of books in Rome and elsewhere” in Humanistica Lovaniensia: Journal of Neo-Latin Studies 34a (1985), pp.65-75 (p.71).

2. T. Kimball Brooker, Upright works: the emergence of the vertical library in the sixteenth century, Thesis (Ph.D.), University of Chicago, 1996, pp.815-821 (“Exhibit 7: Roman bindings with spine titles (late 1530s-1545). Owner’s initials F.T.”) [lists 11 volumes]; T. Kimball Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part II” in The Book Collector 48 (1999), pp.32-53.

3. The couple also had a daughter, named Margarita de Torres: Wenceslao Soto Artuñedo, “La familia malagueña ‘de Torres’ y la iglesia” in Isla de Arriarán: Revista cultural y científica 19 (2002), pp.163-192 (pp.163-164).

4. Thomas Frenz, Die Kanzlei der Päpste der Hochrenaissance (1471-1527) (Tübingen 1986), p.401 no. 1555, recording the transfer of the office in 1538 to one “Ferdinandus”; see the Repertorium Officiorum Romanae Curiae (rorc) database, where “Ferdinandus de Torres” is recorded as a scriptor brevium in 1539. Fernando subsequently obtained the offices of cubicularius (1545) and secretarius (1569). [link]

5. Jesús Suberbiola Martínez, “Los Torres: una saga de altos eclesiásticos” in Creación artística y mecenazgo en el desarrollo cultural del Mediterráneo en la Edad Moderna (Málaga 2011), pp.167-186 (p.171).

6. Claudio De Dominicis, Membri del Senato della Roma Pontificia: Senatori, Conservatori, Caporioni e loro Priori e Lista d’oro delle famiglie dirigenti (secc. X-XIX) (Rome 2009), p.41 (1566-1/4 “Ernando [Ferdinandus] de Torres di S. Eustachio (tennero anche il senatorato)”), p.84 (1560-1/7 “Ferrante Torres di S. Eustachio”). The office of caporione di D. Eustachio was taken in 1581 by his son Juan (1555-1585) (ibid., p.91: “Giovanni Torres di S. Eustachio”).

7. Antonio J. Díaz Rodríguez, “El sistema de agencias curiales de la Monarquía Hispánica en la Roma pontificia” in Chronica Nova 42 (2016), pp.51-78 (pp.71-72); Antonio J. Díaz Rodríguez, “Papal Bulls and Converso Brokers: New Christian agents at the service of the Catholic Monarchy in the Roman Curia (1550-1650)” in Journal of Levantine Studies 6 (2016), pp.203-223 (p.212); Fabrizio D’Avenia, “Obispos españoles en Sicilia: origen judeoconverso y acción pastoral ‘tridentina’ (siglos XVI-XVII)” in Manuscrits. Revista d’Història Moderna 41 (2020), pp.69-94 (pp.74-75).

8. Rosario Camacho Martínez, “Beneficencia y mecenazgo entre Italia y Málagalos Torres, arzobispos de Salerno y Monreale” in Creación artística y mecenazgo, op. cit., pp.17-46 (pp.26-28).

books with supralibros f.t.

(1) Aristoteles, Topicorum libri octo (Basel: Johann Oporinus, 1543), bound with: Plato, Platonis axiochus, aut de morte, liber, Graece & Latine (Basel: Johann Oporinus, 1543)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Libreria antiquaria Hoepli, Manoscritti, miniature, incunabuli, legature, libri figurati dei secoli XVI e XVIII, Milan, 7-9 April 1927, lot 342 & Pl. 92 (“Nel centro dei piatti le iniziali F.T.; dorso a nervi”)

literature

Tammaro De Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI (Florence 1960), no. 2979ter

Anthony Hobson, “Who was F.T.” in Philobiblon 36 (June 1982), pp.166-167 no. 7

T. Kimball Brooker, Upright works: the emergence of the vertical library in the sixteenth century, Thesis (Ph.D.), University of Chicago, 1996, pp.815-821 (“Exhibit 7: Roman bindings with spine titles (late 1530s-1545). Owner’s initials F.T.”), p.820 (“not seen”)

(2) Arsenios Apostolios, Scholia in septem Euripidis tragoedias ex antiquis exemplaribus (Venice: Lucantonio I Giunta, 1534)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana, 18562

literature

Mostra storica della legatura artistica in Palazzo Pitti (Florence 1922), no. 464 (“Mar. marrone, titolo dorato sul dorso, piatti ornati con compartimenti di filetti diritti e curvi e con rabeschi; sul piatto anter. il titolo: Sch | olia | in Eu | ri; sul posteriore le iniziali F.T.”)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 895

Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: An Enquiry into the formation and dispersal of a Renaissance library (Amsterdam 1975), pp.80-86 (“List C: Bindings by Niccolò Franzese”, no. 28)

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 5

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.817 & Fig. 82

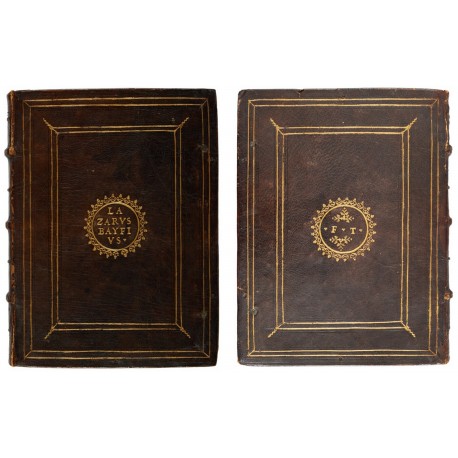

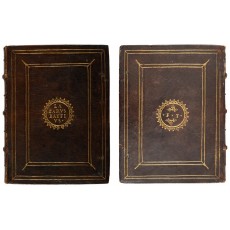

(3) Lazare de Baïf, Annotationes in legem II De captiuis & postliminio reuersis, in quibus tractatur De re nauali, per autorem recognitae (Basel: Hieronymus I Froben & Nikolaus I Episcopius, 1537), bound with: Leonardo Bruni, Rerum suo tempore in Italia gestarum commentarius (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1539)

“F.T.’s First Binder” (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● unidentified owner, ligated initials “APD” on title-page

● Capt. Charles Maxwell Richard Schwerdt (1889-1968)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, autograph letters and historical documents, London, 23-24 March 1953, lot 12 (“contemporary Italian olive morocco, panelled sides with circular cartouches containing the author’s name on the upper cover, and the initials F.T. on the lower cover in gilt”) [lots 1-178 in this sale offered as “The Property of Capt. C.M.R. Schwerdt”; RBH Ash-12]

● McLeish & Sons, London - bought in sale (£10 10s)

● Albert Ehrman (1890-1969), exlibris

● Bernard Quaritch, London; their Catalogue 897: Early continental books (London 1969), item 35 (£80; “The initials on the lower cover are identified as those of Federico Torresani”)

● Arthur Vershbow (1922-2012) and Charlotte Vershbow (1924-2000), joint exlibris, acquired in 1969

● Christie Manson & Woods International Inc., The collection of Arthur & Charlotte Vershbow: The Middle Ages and the Renaissance, New York, 9-10 April 2013, lot 98 (“Provenance: Francisco Torres (initials “F.T.” on lower cover)”) [RBH 2706-98]

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased in the above sale) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #3043]

● Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library: Magnificent Books and Bindings, New York, 11 October 2023, lot 8, unsold at estimate $22,000-$28,000, link; reoffered by Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana VIII, Paris, 3-17 December 2025, lot 34, link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale (€15,240) [RBH pf2525-34]

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 2979bis

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 2

Brooker, Upright works, p.816

(4) Pietro Bembo, Prose (Venice: [Comin da Trino], 1540), bound with Bembo, Gli Asolani (Venice: Comin da Trino, 1540) and Bembo, Rime (Venice: [Comin da Trino], 1540)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Thomas Coke, inscription “Thom a Coke”, presumably Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester (1697-1759) (BnF)

● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Réserve P.Z. 1949 (1-3)

literature

Catalogue général des livres imprimés: Auteurs, collectivités-auteurs, anonymes, 1960-1969, Série 1, Caractères latins, Au-Bibliop (Paris 1973), p.656 (“Reliure veau brun à encadrement d’entrelacs avec fleurons, le plat sup. porte ‘Opere del Bembo’, le plat. inf. F.T. - Ex-libris ms. de Thom a Coke.”)

Brooker, Upright works, p.818

T. Kimball Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part II” in The Book Collector 48 (1999), pp.32-53 (p.47)

(5) Marcus Tullius Cicero, M. Tullii Ciceronis De Philosophia volumen secundum (Venice: Paolo Manuzio, 1541)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Bentinck, Duke of Portland exlibris (Welbeck Abbey), supralibros (gilt-stamped P surmounted by ducal crown to covers) [compare British Armorial Bindings database, as “clearly nineteenth-century in style, and it seems almost certain that they were added to the whole library under the orders of one of the nineteenth-century dukes”, link]

● Sokol Books Ltd, London

● T. Kimball Brooker (purchased from the above, 2022) [Bibliotheca Brookeriana ID #0838; offered by Sotheby's, Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library: The Aldine Collection A–C, New York, 12 October 2023, lot 330, link, unsold against estimate $8000-$10,000, RBH N11294-330; sold January 2026 to]

● G. Scott Clemons

literature

Catalogue of the printed books in the Library of His Grace the Duke of Portland at Welbeck Abbey, and in London (London 1893), p.93 (“De Philosophia. (Vol. I missing.) 2 vols. 8vo. Venet. apud Aldi Filios, 1541”) [link]

(6) Girolamo Ferrari, Ad Paulum Manutium Emendationes in Philippicas Ciceronis (Venice: Paulus Manutius, 1542)

“F.T.’s First Binder” (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Davis & Orioli, London; their Catalogue 162 (London [1959?]), item 46 (“contemporary Venetian red morocco, broad gilt panel on sides, with fleurons and other ornaments in centre of upper cover, the title of the book within a circle surrounded by an ornamental frame, on lower cover the initials of the owner F.T. within a similar frame. A fine perfectly preserved binding”)

● Georges Heibrun, Paris

● Giorgio Angiolo Eduardo Uzielli (1915-1984)

● Austin, University of Texas, Uzielli 252 [opac, link]

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 4

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.817 & Fig. 81

Craig W. Kallendorf & Maria X. Wells, Aldine Press Books at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center The University of Texas at Austin: A Descriptive catalogue (Austin [Online edition, 2008]), no. 248a (“contemporary Roman red morocco gilt; provenance of the copy: “Georges Heilbrun, sold in Feb. 1963 to Uzielli” [link])

(7) Giglio Gregorio Giraldi, Historiae poetarum tam Graecorum quam Latinorum dialogi decem (Basel: Michael Isengrin, 1545)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on upper cover

● Pierre van Zuylen

literature

Société des Bibliophiles et Iconophiles de Belgique, Reliures du moyen âge au 1er empire exposées à la Bibliothèque royale du 16 avril au 5 mai 1955 (Brussels [1955]), no. 31 & Pl. 4 [exhibited as Van Zuylen’s property]

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 2979quat

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 9

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.821

(8) Henricus Glareanus, De geographia (Venice: Giovanni Antonio Nicolini da Sabbio & Melchiorre Sessa, August 1538), bound with: Petrus Apianus, Cosmographiae introductio cum quibusdam geometriae ac astronomiae principijs ad eam rem necessarijs (Venice: Francesco Bindoni & Maffeo Pasini, May 1537), bound with: Piero Valeriano, Compendium in sphaeram per Pierium Valerianum Bellunensem (Rome: Antonio Blado, April 1537), bound with: Georg Peurbach, Nouae theoricae planetarum Georgii Peurbachii astronomi celeberrimi (Venice: Giovanni Antonio Nicolini da Sabbio for Melchiorre Sessa, March 1537), bound with: Ioannes de Sacrobosco, Liber Ioannis de Sacro busto De sphaera (Venice: Francesco Bindoni & Maffeo Pasini, October 1541), bound with Joachim Sterck van Ringelbergh, Institutiones astronomicae ternis libris contentae (Venice: Giovanni Antonio Nicolini da Sabbio & Melchiorre Sessa, January 1535)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Bologna, Biblioteca Communale dell’Archiginnasio, 16 f. IV. 41 (opac “Cuoio di capra marrone su cartone decorato a secco e in oro. Filetti concentrici. Cornice caratterizzata da fogliami pieni, ripresi nello specchio, e archi incrociati. Cartella centrale con fogliami e monogramma ‘F T’. Tracce di due coppie di lacci. Cucitura su tre nervi; carte di guardia marmorizzate del genere caillouté e bianche nuove. Tagli dorati. Legatura eseguita a Roma da Niccolò Franzese: Volume restaurato da Rilegatoria salesiana Bologna, il cui timbro appare nella carta di guardia posteriore” [link, link])

literature

Ilse Schunke, “Die vier Meister der Farnese Plaketteneinbände” in La Bibliofilía 54 (1952) pp.57-91 (p.64 no. 10 & Pl. 1)

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 892

Anthony Hobson, op. cit. 1975, pp.80-86 (“List C: Bindings by Niccolò Franzese”, no. 30)

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 6

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.819

Biblioteca comunale dell’Archiginnasio di Bologna, A fior di pelle: Legature italiane del XV-XVI secolo in Archiginnasio, Bologna 2022, p.37 [link]

(9) Herodianus, De imperatorum Romanorum praeclarè gestis lib. VIII (Basel: Heinrich Petri, 1543)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Luis I de Torres (1494-1553), or Luis II de Torres (1533-1584), signature on endpaper

● Marcantonio Borghese (1814-1886), oval “Ex Libris M.A. Principis Burghesii” (Bragaglia no. 2014)

● Vincenzo Menozzi, Catalogue de la bibliothèque de s. e. d. Paolo Borghese, prince de Sulmona, Première partie, Rome, 16 May-7 June 1892, lot 4515 (“mar. rouge, dos et plats ornés à filets verticaux, tr. dor. et gaufré (rel. anc.). Très bel exempl. dans une jolie reliure.”)

● Arthur Jeffrey Parsons (1856-1915); Agnes Stockton Royall Parsons (1861-1934) [widow, consignor of the library]

● American Art Association, Illustrated catalogue of selections from the private library of the late Arthur Jeffrey Parsons of Washington, D.C., New York, 24 January 1923, lot 130

● Estelle C. Getz (née Cohn) (1880-2 June 1943) [wife of Milton E. Getz (1879-1946), link]

● American Art Association (Anderson Galleries), The notable library formed by Mrs Milton E. Getz, Beverly Hills, California, New York, 17-18 November 1936, lot 157 (“full contemporary red morocco, sides covered with rail-tooling of vertical fillets alternately gilt and blind tooled, with the author’s name gilt-lettered vertically on the front, and the initials f. t. on the back cover; back with gilt tooled cords and author’s name gilt lettered lengthwise in two centre compartments; gilt edges, chased, red ribbon ties torn off with exception of one ribbon; partially rebacked (preserving original centre compartments), some leaves lightly foxed, old signature erased from title-page, old manuscript notations on fly-leaves”; “The signature Lodovicus de Torres is written at the beginning of the notes, and the initials F. T. on the back cover are probably by a member of the same family, for whom the book was originally bound”) [RBH 4278-157] [link]

● unidentified owner - bought in sale ($11)

(10) Blosio Palladio, Coryciana (Rome: Ludovico degli Arrighi & Lautizio Perugino, 1524)

“F.T.’s First Binder” (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● unidentified owner, inscription “Ex libris Joannis Theophili” (opac)

● Biblioteca Ferrajoli [library of manuscripts and some 34,290 printed books, assembled by Filippo Ferrajoli (1851-1926) and his two brothers, Gaetano (1838-1890) and Alessandro (1846-1919); given by Filippo’s widow in 1926 to:]

● Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Fondo Ferrajoli IV, 4734 [De Marinis and Upright works as VI 4734; Hobson as IV 4734, citing De Marinis and writing “with the pressmark misprinted”; opac recording only Stamp.Ferr.IV.4673 without copy-specific details]

literature

De Marinis, op. cit., no. 2979 & Pl. 520

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 1

Brooker, Upright works, p.815 & Fig. 80

T. Kimball Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part II,” op. cit., p.49 & Fig. 6b (title-page)

(11) Plinius Secundus, Naturalis historiae libri XXXVII (Paris: Pierre Regnault, 1543)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on upper cover

● Canons Regular of Saint Anthony of Vienne, in Rome (suppressed 1775), inscription “Ex libris Prioratus Sti Antonii Viennen de Urbe”

● London, British Library, C.47.l.6 [image source]

literature

Anthony Hobson, op. cit. 1975, pp.80-86 (“List C: Bindings by Niccolò Franzese”, no. 40)

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 8

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.821

(12) Florentius Volusenus, De animi tranquillitate dialogus (Lyon: Sébastien Gryphe, 1543)

Bound by Niccolò Franzese (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Rome, Biblioteca Angelica, YY.9.22

literature

Margherita Cavalli & Fiammetta Terlizzi, Legature di pregio in Angelica: secoli XV-XVIII (Rome 1991), no. 6 (“Legatura romana del secolo XVI ascrivibile al periodo Farnese… Dorso rifatto nel XVIII secolo con titolo in oro.”)

Brooker, Upright works, op. cit., p.820 (as Niccolò Franzese)

Brooker, “Who was L.T.? Part II,” op. cit., p.47

(13) Basilio Zanchi, Verborum Latinorum ex variis authoribus epitome (Rome: Antonio Baldo, October 1541)

“F.T.’s First Binder” (Brooker)

provenance

● Fernando de Torres (1521-1590), supralibros, initials “F.T.” on lower cover

● Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliotek / National Library of Denmark, 72, 279

literature

Hobson, op. cit. 1982, pp.166-167 no. 3 & Fig. 2

Brooker, Upright Works, op. cit., p.816