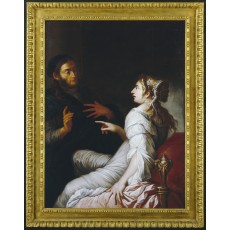

Phryne tempting Xenocrates

Painting, executed in oil on canvas, 128.5 × 96 cm.

“Phryne tempting Xenocrates” is a typical work of Rosa’s late Roman period, reflecting the artist’s absorption with Stoic and Cynic philosophy, and ambition to be known as a sober and philosophical painter of cose morali. The incident depicted is described by Diogenes Laertius (IV, 7) and repeated by Valerius Maximus (LIV, III, 3). According to these sources, Phryne – a courtesan noted for her great beauty – made a wager that she could successfully seduce the philosopher Xenocrates, a disciple of Plato known for his personal dignity and self-restraint. One night Phryne went to the house of this virtuous man claiming to seek refuge from pursuers in the street. Out of compassion for her plight, Xenocrates admitted her, and allowed Phryne to share the couch in his room. But all her female charms could not make the philosopher depart from his strict principles. Eventually Phryne gave up and left the house, telling all who inquired that Xenocrates was not a man but a statue.

For many years, Rosa’s “Phryne tempting Xenocrates” was assumed lost, known only from an account provided by Rosa’s contemporary and biographer, Giovanni Battista Passeri, and by the reproductive print made in 1770 after a version once in the Bessborough collection in England. In 1966, Luigi Salerno discovered our painting in a private collection in Rome, and in 1975, he introduced it into the artist’s catalogue raisonné. It appeared on the market in Sotheby’s, London, 11 April 1990, lot 136. Two other versions have since some to light: one, attributed to “Follower of Salvator Rosa”, was sold in Sotheby’s New York, 17 January 1986, lot 5 ($3410); the other was offered in Christie’s, London, 3 December 1997, lot 72, returning there, 18 November 2015, lot 111 (£152,500).

- Subjects

- Paintings - Artists, Italian - Rosa (Salvator), 1615-1673

- Authors/Creators

- Rosa, Salvator, 1615-1673

- Artists/Illustrators

- Rosa, Salvator, 1615-1673

- Other names

- Phryne, c. 390 BC-c. 330 BC

- Xenocrates, of Chalcedon, c. 396 BC-c. 314 BC

Salvator Rosa

Arnella 1615 – 1673 Rome

Phryne tempting Xenocrates

Rome, c. 1662–1663

Oil on canvas, 128.5 × 96 cm (50 ½ × 37 ¾ in)

provenance

Private collection, Rome — anonymous consignor, Sotheby’s, ‘Old Master Paintings’, London, 11 April 1990, lot 136 — the present owner

literature

Giovanni Battista Passeri, in Le vite de’ pittori, scultori, architetti, ed intagliatori: dal Pontificato di Gregorio xiii. del 1572. fino a’ tempi di Papa Urbano viii. nel 1642. Scritte da Gio: Baglione Romano. Con la vita di Salvator Rosa Napoletano, pittore, e poeta, scritta da Gio: Batista Passari, nuovamente aggiunta (Naples 1733), p.303

Luigi Salerno, Salvator Rosa (Milan 1963), p.151 (‘Frine e Xenocrate’, among ‘Opere perdute’)

Luigi Salerno, ‘Due opere tarde di Salvator Rosa’ in Arte in Europa. Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di E. Arslan (Milan 1966), i, pp.719–721; ii, fig.465 (our version ‘A’ reproduced)

Luigi Salerno, L’opera completa di Salvator Rosa (Milan 1975), p.99 no.179 (our version ‘A’ reproduced)

Jonathan Scott, Salvator Rosa, his life and times (New Haven & London 1995), p.146 pl. 149 (version ‘C’ reproduced)

Helen Langdon, in Salvator Rosa: tra mito e magia, catalogue of an exhibition held in the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, 18 April–29 June 2008, edited by Silvia Cassani (Naples 2008), p.144 no.28 (our version ‘A’ cited; version ‘C’ reproduced)

Stefano Causa, Meglio tacere: Salvator Rosa e i disagi della critica (Naples 2009), p.87 (version ‘C’ reproduced)

Helen Langdon, Salvator Rosa, catalogue of an exhibition held at Dulwich Picture Gallery, 15 September 2010–28 November 2010, and at the Kimball Art Museum, Fort Worth, 12 December 2010–27 March 2011 (London 2010), p.199 (cited)

Caterina Volpi, Salvator Rosa (1615–1673): “pittore famoso” (Rome 2014), p.586 no.310 (our version ‘A’ cited; version ‘C’ reproduced)

‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ is a typical work of Rosa’s late Roman period, reflecting the artist’s absorption with Stoic and Cynic philosophy, and ambition to be known as a sober and philosophical painter of cose morali.1 In his predilection for obscure subjects and themes of moral philosophy, Rosa followed Rembrandt, and Luigi Salerno considers the background of our picture, vibrating with dim light, its red and rust shades, the pearls in Phryne’s hair, and the use of bituminous veils, to be a conscious imitation of Rembrandt’s style.2

The incident depicted is described by Diogenes Laertius (iv, 7) and repeated by Valerius Maximus (liv, iii, 3).3 Phryne was a courtesan noted for her great beauty, the most notorious woman in Athens of the fourth century bc. According to these sources, she made a wager that she could successfully seduce the philosopher Xenocrates, a disciple of Plato in the Athenian Academy, known for his personal dignity and self-restraint. One night Phryne went to the house of this virtuous man claiming to seek refuge from pursuers in the street. Out of compassion for her plight, Xenocrates admitted her, and allowed Phryne to share the one small couch in his room. But all her female charms could not make the philosopher depart from his strict principles. Eventually, Phryne gave up and left the house, telling all who inquired that Xenocrates was not a man but a statue.

Rosa’s composition consists of two figures in half-length, Phryne in profile, leaning back against a cushion on a dishevelled bed, and the standing figure of Xenocrates. The two figures look directly at each other; Xenocrates holds up one hand as a barrier to restrain himself, and uses the other to make an admonitory gesture. Phryne points right at Xenocrates and her reclining posture and parted legs leave no doubt about her erotic intentions. In the story, Phryne is described as nude, however Rosa paints her fully clothed, and suggests her lasciviousness with gestures and expressions. Another painter would have emphasised the physical relationship; Rosa places his emphasis on the moral one, and presents the incident as an example of abstinence and continence shown through the philosopher’s exceptional moral character.

Rosa’s contemporary and biographer, Giovanni Battista Passeri (circa 1610–1679), cites the work as a perfect example of the moral seriousness of Rosa, who always avoided obscenities and lustful looks:

Osservai questa sua modestà astinenza in un quadro di sua mano, ove rappresentò il caso dell’impudica Frine, e il continente Senocrate, e con tutto chè la necessità dell’ istoria astringa Frine a comparire del tutto nuda agl’occhi dell’onesto Filosofo per invaderlo con maggior violenza, e con maggior validità alla caduta de’suoi assalti lascivi, nulla di meno la tenne coperta del tutto, e appena lasciò vederne ignuda la metà del braccio sinistro; ma con tanto artificio, che nè meno poteva dirsi discoperto del tutto.4

I noticed this modest abstinence of his in a picture made by him, where he represented the story of immodest Phryne and moderate Xenocrates, and with all that the necessity of history obliges Phryne to appear completely naked to the eyes of the honest philosopher in order to fill him with stronger violence, and force him more easily to surrender to her lustful assaults; nevertheless he kept her completely covered, and just left naked half of her left arm; but with such skill, that she could be said completely undressed.

‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ was probably executed by Rosa in 1662 or 1663, just before he began a series depicting pre-Socratic philosophers and natural magicians.5 At this time Rosa was producing series of didactic paintings of philosophers for the Sicilian collector Antonio Ruffo (1610–1678)6 and for Queen Christina of Sweden.7 The rare subject ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ can not be identified in their inventories, and it could be that Rosa painted it ‘on speculation’ for a group exhibition in Rome. In August 1662, Rosa exhibited in the cloister adjacent to San Giovanni Decollato five paintings, of which two were acquired afterwards by Ruffo, and another (eventually) by Carlo de’ Rossi; the remaining two paintings failed to attract buyers.8 Rosa does not report what these two pictures were, however ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ is consistent with Rosa’s stated intention in 1662 to show unusual subjects ‘in every way and altogether new, and never painted by anyone’.9

Version A

Like many of Rosa’s compositions, ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ is known in multiple versions. Rosa signed his work unsystematically, and discriminating between prime versions and replicas is problematic. In letters dated 1666, the painter complains of his difficulty in finding good copyists,10 and from this evidence it is conjectured that the contemporary replicas were not painted by Rosa himself, though he certainly authorized them, and retouched some by his own hand.11 Passeri names two ‘pupils’ or assistants in Rosa’s studio who might have performed such labour, and also identifies ‘followers’ with uncertain connections to Rosa’s studio. Rosa’s second son Augusto (1657–c. 1737) had entered the studio at the age of eight, and eventually became a painter in his own right.12 After his father’s death, in 1673, Augusto continued to live in the family house in via Gregoriana, surrounded by unsold paintings. It is believed that he produced copies of these which were passed off as originals;13 the nefarious practice is supposed to have continued long after Augusto’s death.14

For many years, Rosa’s ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ was assumed lost, known only by the reproductive print made after a version once in the Bessborough collection in England (Fig. 3). In 1966, Luigi Salerno discovered in a private collection in Rome a painting substantially corresponding to the print (Version a), and in 1975 he introduced that painting into Rosa's catalogue raisonné.15 Although the dimensions are not stated by Salerno, it is unquestionably the picture which appeared in Sotheby’s in 1990, and is here offered for sale (Figs. 1–2).16

Version B

When the painting arrived in the London in 1990, Sotheby's, seemingly unaware of any other version of Rosa's composition, and oblivious to Salerno’s publications of 1966 and 1975, catalogued it as ‘probably’ the painting formerly in the Bessborough collection.17 The Bessborough picture (Version b) is first documented in the collection of George Cholmondeley, Viscount Malpas. He sold it circa 1747 to William Ponsonby, latterly 2nd Earl Bessborough, and for the next hundred years it remained in the Bessborough family. In 1770, as Rosa’s legend and influence reached its apex, the painting was engraved for Boydell’s A Collection of Prints engraved after The Most Capital Paintings in England (London 1769–1772) (see Fig. 3). Later generations of the family did not esteem the picture so highly18 and they twice consigned it to the auction salerooms, where it twice failed to realize their expectations. On 1 April 1848, the picture was offered a third time by Messrs. Christie and Manson, in a sale of property belonging to the late 3rd Earl removed from Cavendish Square; it again failed to find a buyer, and returned to the family. The picture reappeared at Christie’s in 1850, when it was bought by a picture-dealer, Peter Norton, for John Rushout, 2nd Baron Northwick, of Northwick Park, Worcestershire. Northwick died intestate in 1859 and his collection was dispersed at auction. ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ was bought by Peter Norton (for two-thirds of the price he had paid in 1850), whereupon the chain of provenance is broken.

from an intermediary drawing by Richard Earlom (image 43.5 × 35.2 cm)

(image courtesy of Sotheby’s New York)

In 1986, a painting corresponding to Boydell's print appeared in Sotheby’s, New York. The dimensions of the canvas (54 ½ × 37 ½ in, 138.5 × 95.5 cm) approximate the dimensions recorded on the print: ‘3 F by 4 F, 6 I in Height’ (54 × 36 in, 137.2 × 91.4 cm), and it probably is the Bessborough picture (Fig. 4). The consignor was the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which had received the painting by donation in 1951. While in the Museum’s possession, it was recognized as a Salvator Rosa, however the subject was unknown (later to be misidentified as ‘Tarquin and Lucretia’).19 Sotheby's correctly catalogued it as ‘Xenocrates and Phryne’, with reference to Salerno’s 1975 catalogue raisonné (‘This painting derives from a work by Rosa in a private collection, Rome’).20

Version C

As the Bessborough picture was presented at Christie's in 1848, the auctioneer, William Manson, ‘stated that there was another in the Grosvenor collection, somewhat different to this one, also engraved ― that was known to be the original picture, but there was nothing to show that the master had not painted the present one’.21 This other version (Version c) is first recorded in a sale of pictures belonging to Robert Grosvenor, 1st Marquess Westminster (1767–1845), in 1812. It passed thereafter into the collection of his cousin, Thomas, General Grosvenor (1764–1851), who in 1836 consigned the picture to Christie’s, where it evidently was seen by the auctioneer William Manson. The picture failed to reach its reserve, and was returned to General Grosvenor. Two years later (and with the rank now of Field Marshall), Thomas Grosvenor chose to rebuild his house. A sale on the premises was conducted by Foster’s prior to commencement of works, and on 15 March 1848 – a fortnight before the sale at Christie’s of the Bessborough picture – the Grosvenor version of ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ came under the hammer. On this occasion the picture was sold, to Charles O’Neil, a picture-dealer of Golden Square, Soho, whereupon the chain of provenance is broken (O’Neil is declared bankrupt in 1850).

(120 × 96 cm) (image soure)

(120 × 96.2 cm) (image source)

In 1964, a painting of the subject was discovered in a coach house in the English countryside, where it had been stored unframed and much neglected. In enquiries about the picture addressed to the Director of the Courtauld Institute, the Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, the Heim Gallery in London,22 and Luigi Salerno in Rome,23 the owner, David Kirby, reported its dimensions as 130 × 100 cm. It is likely that this is the Grosvenor picture. The painting was sent for relining and restoration in 1983–1984, during which it was reduced to 120 × 96 cm (47 ¼ × 37 ¾ in). In 1997, it was introduced as ‘The Property of a Gentleman’ into a sale conducted by Christie’s, London, catalogued as ‘probably’ the Bessborough painting; it returned to Christie’s, in 2015, as ‘possibly’ the Bessborough picture (Figs. 5–6).24

Appendix | Provenance of Version B

George Cholmondeley, Viscount Malpas, from 1733 3rd Earl of Cholmondeley (1703–1770), of Arlington Street, London, until circa 1747(?)25 — William Ponsonby, Viscount Duncannon, from 1758 2nd Earl Bessborough (1704–1793), of Bessborough, Co. Kilkenny, and Roehampton, by 177026 — offered as the property of the late Earl of Bessborough by his heir, Frederick Ponsonby, 3rd Earl Bessborough (1758–1844), at Christie’s, Pall Mall, 5–7 February 1801, lot 87 (bought in £183 15s)27 — offered as the property of ‘A Noble Earl deceased’ at Bessborough House, Roehampton, London, by Christie’s, 7 April 1801, lot 65 (bought in £110 5s)28 — offered as the property of ‘the late Right Hon. Frederick Earl of Bessborough, and removed from the Family Residence in Cavendish Square’, by Christie’s, King Street, 1 April 1848, lot 81 (bought in 94 guineas)29 — offered by the executors of John, 4th Earl of Bessborough (1781–1847), West Hill, Wandsworth, by Christie’s, King Street, 10–11 July 1850, lot 18530 — where bought (39 guineas) by Peter Norton, picture-dealer of Soho Square, London — offered as the property of John Rushout, 2nd Baron Northwick (1770–1859), of Northwick Park, Worcestershire, by Phillips, at Thirlestaine House, Cheltenham, 26 July 1859 etc. (11 August 1859), lot 106231 — where bought (£27 6s) by Norton

Probable later provenance: Fred M. Dean, Beverly Hills, by 1951 — gift of Mr. and Mrs. Fred M. Dean to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (acquisition number M.51.9) — sold as the property of LACMA by Sotheby’s, ‘Important Old Master Paintings’, New York, 17 January 1986, lot 5 (presented as by a ‘Follower of Salvator Rosa’, sold for $3410)

Appendix | Provenance of Version C

[possibly Richard Grosvenor, 1st Earl Grosvenor (1731–1802)]32 — Robert Grosvenor, 2nd Earl Grosvenor, Viscount Belgrave until 1802, when succeeded as 2nd Earl Grosvenor, from 1831 1st Marquess of Westminster (1767–1845), of Grosvenor House, London, and Eaton Hall, Cheshire, by 181233 — offered as the property of ‘Lord Grosvenor’, by Peter Coxe, London, 2 July 1812, lot 70 (marked as sold, but perhaps bought in £14 3s 6d)34 — offered as the property of ‘Grosvenor’, by Christie’s, London, 6 February 1815, lot 66 (bought in £23 2s)35 — offered as the property of ‘Gen.l Grosvenor’ (Thomas, General Grosvenor, 1764–1851; cousin of Robert Grosvenor, 2nd Earl Grosvenor), by Christie’s, London, 25 June 1836, lot 4036 (bought in 25 guineas) — offered as the property of ‘[Thomas] Field Marshall Grosvenor’, of 42 Grosvenor Street, by Edward Foster & Son, London, 15 March 1848, lot 6637 — purchased (£26 5s) by the picture-dealer Charles O’Neil

Probable later provenance: David Kirby, Hertford, Herts, England, by 1964 — consigned as ‘The Property of a Gentleman’, Christie’s, ‘Important Old Master Pictures’, London, 3 December 1997, lot 72 (left unsold against its estimate; purchased after sale by) — Victoria Press (1927–2015) — her sale by Christie’s, ‘Cheyne Walk, An Interior by Victoria Press & A House on Ham Common, The Collection of Tom Craig’, London, 18 November 2015, lot 111 (estimate £60,000-£80,000; realised £152,500 inclusive of premium) — with Robilant + Voena, Milan & London, 2016 (exhibited TEFAF Maastricht, 11–20 March 2016; link)

1. Rosa’s production in these years is discussed by Helen Langdon, ‘Salvator Rosa, gli ultimi anni (1660–1673)’ in Salvator Rosa: tra mito e magia, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, 18 April–29 June 2008 ([Naples] 2008), pp.47–57; H. Langdon ‘The Representation of Philosophers in the Art of Salvator Rosa’, a paper presented at the annual meeting of the Renaissance Society of America, Venice, 2010, in kunsttexte.de, Nr. 2, 2011 (www.kunsttexte.de).

2. Luigi Salerno, ‘Due opere tarde di Salvator Rosa’ in Arte in Europa. Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di E. Arslan (Milan 1966), i, p.720.

3. Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, translated by R.D. Hicks, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, ma 1972), i, pp.380–382; ‘Abstinentia et continentia. Xenocrates Academicus’ of Valerius Maximus, Factorum dictorumque memorabilium (Leiden 1726), i, p.363. The incident is the subject of a madrigale, ‘Senocrate’, in a work familiar to Rosa: G.B. Marino’s La Galeria (Venice 1619; revised edition, La Galleria dell’inclito Marino considerata vien dal Paganino [Gaudenzio], Pisa 1648, concludes with a poem dedicated to Rosa). The subject is rare, almost unprecedented in painting; compare Gerrit van Honthorst (1592–1656), ‘Steadfast Philosopher’, signed and dated 1623 (E.K.J. Reznicek, ‘The significance of a table leg: some remarks on Gerard van Honthorst’s “Steadfast Philosopher”’ in Hoogsteder-Mercury, 11, 1990, pp.22–27); and Giovanni Battista Langetti (1635–1676), ‘Frine tenta Senocrate’ (Marina Stefani Mantovanelli, ‘Langetti e il tema storico di “Frine tenta Senocrate”: possibili implicazioni iconologiche’ in Un’identità: custodi dell’arte e della memoria, edited by Giuseppe Maria Pilo, Monfalcone 2007, pp.271–275). Angelica Kauffman painted the subject between 1788 and 1793 (picture lost after 1879); it is believed the source of her idea and composition was Rosa’s painting (Wendy W. Roworth, ‘The gentle art of persuasion: Angelica Kauffman’s Praxiteles and Phryne’ in The Art Bulletin 65, 1983, pp.488–492).

4. G.B. Passeri, in Giovanni Baglione, Le vite de’ pittori, scultori, architetti, ed intagliatori: dal Pontificato di Gregorio xiii. del 1572. fino a’ tempi di Papa Urbano viii. nel 1642. Scritte da Gio: Baglione Romano. Con la vita di Salvator Rosa Napoletano, pittore, e poeta, scritta da Gio: Batista Passari, nuovamente aggiunta (Naples 1733), p.303 (text here transcribed); reprinted G.B. Passeri, Vite de pittori, scultori ed architetti: che anno lavorato in Roma, morti dal 1641 fino al 1673 (Rome 1772), pp.438–439; Die Künstlerbiographien von Giovanni Battista Passeri, nach den Handschriften des Autors herausgegeben und mit Anmerkungen versehen von Jacob Hess, Römische Forschungen der Bibliotheca Hertziana, 11 (Leipzig 1934), p.399.

5. Helen Langdon, in Salvator Rosa: tra mito e magia (op. cit.), p.144 (as ‘1662–63’). In a letter to Giovanni Battista Ricciardi (1623–1686) dated 26 January 1670, Rosa complains of the cold, such that he could not warm himself by ‘the torch of Cupid, or even the embraces of Phryne’ (Salvator Rosa, Lettere: raccolte da Lucio Festa, edited by Gian Giotto Borrelli, [Bologna] 2003, p.393 no. 375: ‘Eppure non posso riscaldarmi, né mi riscalderiano né le faci di Cupido né gl’abracciamenti di Frine’). A drawing in the Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig (Inv.-Nr. NI. 8687) of c. 1662–1663 might however be a study for the figure of Xenocrates; see Salvator Rosa: Genie der Zeichnung: Studien und Skizzen aus Leipzig und Haarlem, edited by Herwig Guratzsch (Cologne 1999), p.256 no. 161.

6. Jeroen Giltaij, Ruffo en Rembrandt: over een Siciliaanse verzamelaar in de zeventiende eeuw die drie schilderijen bij Rembrandt bestelde (Zutphen 1999), appendices; Rosanna De Gennaro, Per il collezionismo del Seicento in Sicilia: l’inventario di Antonio Ruffo principe della Scaletta (Pisa 2003). At his death Ruffo had a collection of 364 paintings, mainly by contemporary Roman and Neapolitan artists, including a long series of half-length figures of philosophers painted by Giacinto Brandi, Guercino, Mattia Preti, Rosa, and others. Ruffo also owned paintings by Rembrandt and Poussin, and Rosa’s emulation of Rembrandt in ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ (his use of rosso ruggine and velatura bituminosa, see note 2 above), and the stiff classicism adopted from Poussin, suggest a direct appeal to the Sicilian collector.

7. See the inventories of her heir, marchese Pompeo Azzolini, taken in 1689 and 1692 (Getty Provenance Index Databases, Archival Inventories, I-3444, I-3445; http://www.getty.edu).

8. Lettere / Salvatore Rosa; raccolte da Lucio Festa, edited by Gian Giotto Borrelli (Naples 2003), pp.298–299 no. 277: SR to G.B. Ricciardi, 16 September 1662: ‘Ve ne furno due altri pezzi, i quali come che non furno fatti per questo fine, non ne dirò di vantaggio. E questo è quanto alla festa’; Xavier F. Salomon, ‘“Ho fatto spiritar Roma”: Salvator Rosa and seventeenth-century exhibitions’ in Salvator Rosa, catalogue of an exhibition held at Dulwich Picture Gallery, 15 September 2010–28 November 2010 (London 2010), pp.87–89.

9. Lettere / Salvatore Rosa (op. cit.), p.294 no. 272: SR to G.B. Ricciardi, 29 July 1662: ‘…i soggetti de’ quali sono del tutto e per tutto nuovi, né tocchi mai da nessuno.’

10. Lettere / Salvatore Rosa (op. cit.), pp.353–356 nos. 331–334: SR to G.B. Ricciardi, 13 November 1666–12 December 1666.

11. Luigi Salerno, ‘Salvator Rosa at the Hayward Gallery’ in The Burlington Magazine 115 (December 1973), p.827.

12. For details of Augusto’s career, see Ilaria Miarelli Mariani, ‘Lettere di Augusto Rosa a Giovan Battista Ricciardi (1673–1686)’ in Studi secenteschi 44 (2003), pp.281–313; I. Miarelli Mariani, ‘Lunette a “paesi” di Augusto Rosa nel chiostro di Sant’Andrea delle Fratte a Roma’ in Salvator Rosa e il suo tempo 1615–1673, edited by Sybille Ebert-Schifferer (Rome 2010), pp.425–434.

13. Luigi Salerno, ‘Salvator Rosa: Postille alla mostra di Londra’ in Arte Illustrata 55–56 (1973), pp.408–414 (especially p.412); Jonathan Scott, Salvator Rosa, his life and times (New Haven & London 1995), pp.191–194, 220; Miarelli Mariani, ‘Lettere di Augusto Rosa’ (op. cit.), pp.284–285.

14. The Letters of Sir Joshua Reynolds, edited by John Ingamells and John Edgcumbe (New Haven & London 2000), letter 162 pp.172–174: Sir JR to the Duke of Rutland, 4 October 1786, reporting double-dealing by the Romans: ‘this trick has been played to my knowledge with Pictures of Salvator Rosa by some of his descendants who are now living at Rome, who pretend that the Pictures have been in the family ever since their ancestor’s death’. The artist Thomas Jones, a lodger in Rosa’s house in 1776, recorded ‘The Walls of all the rooms were covered with landscapes painted in Water Colour by old Salvator’s pupils…’ (‘The Memoirs of Thomas Jones’, edited by A.E. Oppe, The Annual Volume of the Walpole Society, 32, 1946–1948, p.87).

15. Luigi Salerno, ‘Due opere tarde di Salvator Rosa’ (op. cit.), i, pp.719–721; ii, fig. 465; L. Salerno, L’opera completa di Salvator Rosa (Milan 1975), p.99 no. 179 (located ‘Roma, propr. priv.’). The original bromide photograph (22.5 × 17 cm) used in 1966 and 1975 has survived (Los Angeles, The Getty Research Institute, ‘Luigi Salerno Research Papers’, Box 11). It is stamped on verso ‘foto Vasari s.p.a – Roma. | Via Condotti, 39 – Via Ludovisi, 6–8 | Piazza Esedra, 61 – Viale Tiziano, 104’ and ‘Lastra Nº 915–65 [numerals handwritten]’, with annotations relating to its usage in 1966 and 1975, but no details of the Roman owner.

16. Salvator Rosa’s house descended within his family, with genuine paintings still inside, until the early years of the twentieth century: portraits of the artist’s first-born son, Rosalvo (d. 1656), and his wife Lucrezia Paolini (d. 1696), were acquired from his descendant, Augusto Rosa, in 1914 (Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini); see Leandro Ozzola, Vita e opera di Salvator Rosa: pittore, poeta, incisore con poesie e documenti inediti (Strassburg 1908), p.251: ‘Essi si trovano a Roma, presso una signora degli eredi Rosa’; Salerno, L’opera completa (op. cit.), nos. 28, 117; Salvator Rosa: tra mito e magia (op. cit.), no. 9. It is congenial to imagine ‘Phryne tempting Xenocrates’ in situ almost until our times.

17. Sotheby’s, ‘Old Master Paintings’, London, 11 April 1990, lot 136 (£26,400).

18. Letter of Lady Caroline Lamb and William Ponsonby (youngest son of the 3rd Earl Bessborough), to Lady Morgan, 27 May 1823: ‘The Phryne you name, has reddish, or rather, yellow hair, and is by no means decent in her drapery. I never could endure that picture’ (printed in Lady Morgan’s memoirs: autobiography, diaries and correspondence, London 1863, ii, p.167).

19. Burton Fredericksen and Federico Zeri, Census of pre-nineteenth-century Italian paintings in North American public collections (Cambridge, ma 1972), pp.177, 591 (as ‘Unknown Scene [Tarquinius and Lucretia?]’). The chain of provenance given in the Getty Provenance Index Databases (Public Collection Record 391) is a conflation of the Bessborough and Grosvenor versions (http://www.getty.edu).

20. Sotheby’s, New York, ‘Important Old Master Paintings’, 17 January 1986, lot 5, attributed to a ‘Follower of Salvator Rosa’. The present location of the painting is unknown.

21. ‘Sale of the Collection of Pictures of the late Earl of Bessborough’ in The Morning Post (London), 3 April 1848, p.3.

22. Getty Research Institute, Heim Gallery Records, 910004*, Box 47A, folder 64: letter to the Heim Gallery from David Kirby, Hertford, Hertfordshire, dated 9 November 1981. In an accompanying letter (to the Keeper of Prints and Drawings, British Museum, of the same date), Kirby reports ‘It has been sadly neglected and damaged and is unframed. It measures 1,000 × 1,300 mm’.

23. Getty Research Institute, Luigi Salerno Research Papers, 2000.M.26*, Series i, Box 14 (folder marked ‘Rosa Paintings’): letter to Salerno from David Kirby, dated 26 November 1982, with two colour photographs of the unrestored painting attached. Cf. Hereford Civic Society, ‘Newsletter’, Summer 2015, p.3, resume of a talk (‘Looking after an Old Master’) by David Kirby: ‘After the AGM, David Kirby treated us to an intriguing true life story of detection in high art. On buying an old coach house in 1964, he found himself in possession of a most unfashionable oil painting of two figures in dark, swirling colours in very poor condition. Numerous times it almost went on the bonfire, but there was something about its quality that piqued his interest. A chance finding of a reference book in Italy gave the first clue; it seemed to match a description of a painting by the C17 artist Salvator Rosa depicting the philosopher Xenocrates resisting the advances of a courtesan. But there is more than one version in existence so was David’s painting the real thing, or just a copy? After a long and circuitous route via the Courtauld Institute and Rhode Island University, it was declared to be genuine and was sold by auction at Christie’s in 1997. It is thought to be a self-portrait of Rosa and his long-term model and mistress Lucrezia.’ (link).

24. ‘Important Old Master Pictures’, 3 December 1997, lot 72 (left unsold against its estimate of £70,000–100,000; purchased after the sale by Victoria Press (1927-2015); her sale by Christie’s, ‘Cheyne Walk, An Interior by Victoria Press & A House on Ham Common, The Collection of Tom Craig’, 18 November 2015, lot 111, estimate £60,000-£80,000; realised £152,500 inclusive of premium). Reproduced by Jonathan Scott, Salvator Rosa, his life and times (New Haven & London 1995), p.146 pl. 149 (located in a ‘Private collection, uk’) and again in Salvator Rosa: tra mito e magia (op. cit.), pp.144–145 no. 28 (‘Collezione privata’).

25. George Cholmondeley acquired works of art in Italy during a tour in 1721 (John Ingamells, A Dictionary of British and Irish travellers in Italy, 1701–1800, New Haven 1997, p.203). He lost influence on the fall of his father-in-law Walpole in 1742, and by 1747 was selling chattels to settle debts: ‘his paintings he put such prices as he thought propper being very high. and acquainted or obliged his Creditors to take pictures at that price or nothing. whereby in such manner he dispersed his Collections. – & got discharges from them – being seller & actioneer [sic] to himself’ (George Vertue, Vertue Note Books, iii, The Annual Volume of the Walpole Society, 22, 1933–1934, p.157; cf. The Yale edition of Horace Walpole’s correspondence, 19, edited by W.S. Lewis, New Haven 1955, p.405, letter of HW to Sir Horace Mann, 19 May 1747: ‘Your brother [Galfridus Mann] is gone over the way [to Arlington Street] with Mr. [Francis] Whithed to choose some of Lord Cholmondeley’s pictures for his debt’). A posthumous sale was conducted by Christie’s on 14–15 February 1777 (Lugt 2640).

The Cholmondeley provenance is attested by a letter of William Francis Spencer Ponsonby, youngest son of the 3rd Earl Bessborough (1787–1855) to Lady Caroline Lamb, dated 20 April 1823: ‘Dearest Sister, I send you all that I can recollect about Salvator Rosa’s pictures… My brother [John William Ponsonby, 4th Earl of Bessborough (1781–1847)] had two, Zenocrates and Phryne, still at Roehampton, and a smaller one, which you must recollect, Jason and the Dragon [sold by Frederick, 3rd Earl of Bessborough, in 1801]… The former was bought by my grandfather [William Ponsonby, 2nd Earl of Bessborough (1704–1793)], at the sale of the old Lord Cholmondeley’ (printed in Lady Morgan’s memoirs, op. cit., ii, pp.161–163). At the sale of the collection of James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, 6–8 May 1747 (Lugt 665), Lord Bessborough acquired Rosa’s ‘Jason and the Dragon’ (lot 117, £53 11s); it was sold in 1801.

26. If not in fact acquired from Lord Cholmondeley circa 1747 (see note above), ‘Phyrne and Xenocrates’ was surely in Bessborough ownership by 1770, when it was engraved (by Simon François Ravenet from an intermediary drawing by Richard Earlom) with a legend reading ‘From the Original Picture… In the Collection of the Right Hon.ble the Earl of Bessborough’ (see Fig. 2). The print was published in John Boydell’s A Collection of Prints Engraved after the Most Capital Paintings in England (London 1769–1772), ii, pl. 9. See J. Boydell, Catalogue raisonné d’un recueil d’estampes d’après les plus beaux tableaux qui soient en Angleterre (London 1779), pp.21–22, no. ix: ‘Phryne cherchant à séduire Xenocrate, d’après le Tableau du Cabinet de M. le Comte de Besborough. 15 [Pouces] sur 20 de haut. Prix 7 ch[elins] 6 s[ols]’; and Peter Tomory, Salvator Rosa, his etchings and engravings after his works, catalogue of an exhibition, John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art (Sarasota 1971), no. 22.

27. Catalogue of the well known valuable and truly capital collection of pictures … formed by the late Earl of Besborough [sic] (Lugt 6190), 3rd day, p.18 lot 87: ‘Xenocrates and Phryne, a capital Picture by this Celebrated Artist, whose powers were equal to every subject, in a stile peculiar to himself; a very graceful and expressive Group. N.B. Engraved in Mr. Boydell’s Collection’ (link). According to George Redford (Art Sales, London 1888, i, pp.84–85), the picture sold to a ‘Mr. Walton’ (link).

28. Catalogue of the Capital, Well-known, and Truly Valuable Collection … the Property of a Noble Earl, Deceased (Lugt 6226), lot 65: ‘Xenocrates and Phryne; a capital Picture by this celebrated Artist, whose Powers were equal to every Subject: a very graceful and expressive Groupe. N.B. This is engraved in Mr. Boydell’s Collection’. Recorded in the possession of the Earl of Bessborough in 1824 (Lady [Sydney] Morgan, The Life and Times of Salvator Rosa, London 1824, ii, p.366).

29. Catalogue of Capital Pictures, being the Collection formed by the late Right Hon. Frederick Earl of Bessborough (Lugt 18973), lot 81: ‘Xenocrates and Lais—the celebrated engraved picture’.

30. Catalogue of the Valuable Collection of Italian, French, Flemish, Dutch, and English Pictures, the property of the late Right Hon. The Earl of Bessborough, and removed from West Hill, Wandsworth: comprising Xenocrates and Lais, the cebrated [sic] engraved Picture, by Salvator Rosa … which will be Sold by Auction (Lugt 19951), lot 185: ‘Xenocrates and Lais’.

31. A catalogue of the pictures in the galleries of Thirlestane House, Cheltenham; the residence of the Right Hon. Lord Northwick [compiled by Henry Davies] (Cheltenham 1858), p.8 no. 49 (displayed in the Parthenon Gallery); Catalogue of the late Lord Northwick’s Extensive and Magnificent Collection of Ancient and Modern Pictures (Lugt 25025), p.99, lot 1062: ‘Xenocrates and Lais. The engraved picture. From the Collection of the Earl of Bessborough’.

32. Richard Grosvenor purchased paintings in Italy through the agency of Richard Dalton. Some appeared in a posthumous sale by Christie’s on 13 October 1802 (Lugt 6503); others – identified as ‘Purchased in Italy by Mr. Dalton, for the late Earl Grosvenor’ (or similar) – were sold by Peter Coxe on 27 June 1807 (Lugt 7278); many were retained in the family collection.

33. Robert Grosvenor made two successive tours in Italy (1786–1790), but is not known to have acquired works of art (Ingamells, op. cit, p.74). In 1806, he bought the collection of Welbore Ellis Agar (1735–1805), including – but possibly not limited to – 128 paintings which had been consigned for sale by Christie’s on 2–3 May 1806 (Lugt 7080a). In order to make room for these, he sold his own, family pictures, and unwanted Agar pictures, in 1807 (Lugt 7278) and 1812 (Lugt 8219).

34. Valuable paintings of the Italian, Flemish, Dutch, French, and English masters (Lugt 8219), lot 70: ‘Zenocrates and Phryne. This Picture was ever deemed and celebrated as a masterly proof of this great Artist’s skilful and powerful pencil’.

35. Valuable assemblage chiefly of Italian pictures (Lugt 8720), lot 66: ‘Xenocrates and Phryne’. The Getty Provenance Index Databases (Description of Sale Catalog Br–1293’) identifies the vendor as Thomas Grosvenor (http://www.getty.edu).

36. Catalogue of a valuable collection of Italian, French, Flemish, and Dutch Pictures (Lugt 14412), lot 40: ‘S. Rosa. Tarquin and Lucretia; the celebrated engraved picture’. The auctioneer’s copy of the sale catalogue is annotated with the vendor’s name (‘Gen.l Grosvenor’) and reserve (50 guineas).

37. Catalogue of the remaining household furniture, fixtures … also, a collection of pictures, including many works of an interesting character, some of which were formerly in the Grosvenor Gallery. Attention may be directed to Xenocrites and Phryne, by Sal. Rosa … the Property … of Field Marshal Grosvenor … which will be sold by auction … on the premises, No. 42 Grosvenor Street (Lugt 18944), lot 66 (hanging in Drawing Room): ‘Xenocrites and Phryne; engraved by Boydell. This work was formerly in the Grosvenor Gallery, where the companion now hangs’.