Collezione di tiramenti rari di celebrate statue antiche 1755

A series of forty-four large chalk drawings (circa 482/525 × 345/360 mm) of exemplary antique statues in Rome, perhaps executed for an English patron, or with a view toward eventual publication in England, as they are scaled in both English piedi and Roman palmi. Nicolas Mosman is known chiefly by a set of drawings of paintings in Roman collections, produced between 1764 and 1787 for Brownlow Cecil, 9th Earl of Exeter. In Rome, Mosman was linked socially and professionally with the painter Mengs, the archaeologist Winckelmann, the painter-dealer Thomas Jenkins, and the restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi. His selection of sculpture reflects the revaluation of antique sculpture then being undertaken by Mengs and Winckelmann, and the commercial transactions of Jenkins and Cavaceppi. In addition to the narrow canon of masterpieces established by Mengs, Mosman documents recent additions to the Capitoline collection (purchases by Clement XII from the Albani and Odescalchi collections, and by Benedict XIV from the D'Este collection and from digger-dealers), and sculptures within the Barberini, Borghese, Casali, Farnese, Giustiniani, Ludovisi, Medici, Pighini, Spada, and Verospi family collections recently lauded by Winckelmann. Four drawings depict antique sculptures restored by Bartolomeo Cavaceppi and introduced onto the market in 1754/1755, 1764, 1766/1768 respectively; another two are of modern sculptures: a bronze statue of Mercury by Guglielmo della Porta in the Palazzo Farnese and a marble statue of Santa Susanna by François Duquesnoy in S. Maria di Loreto. The drawings were mounted on album leaves in the nineteenth century, when a title-leaf and a contents-leaf were supplied, and the sheets numbered sequentially in ink. The date “1755” in the title perhaps was found on a portfolio that previously held the loose sheets; it could be the date of the earliest drawing, made soon after Mosman's arrival in Rome.

- Subjects

- Archaeology, Greek & Roman - Early works to 1800

- Sculpture, Greco-Roman

- Authors/Creators

- Mosman, Nicolas, 1727-1787

- Artists/Illustrators

- Mosman, Nicolas, 1727-1787

- Owners

- Hickes, Elizabeth Katharine Theresa, 1846-1923

- Other names

- Brownlow Cecil, 9th Earl of Exeter, 1725-1793

- Cavaceppi, Bartolomeo, c. 1716-1779

- Jenkins, Thomas, c. 1722-1798

- Mengs, Anton Raphael, 1728-1779

- Winckelmann, Johann Joachim, 1717-1768

Mosman, Nicolas

Haroué (France) 1727 – 1787 Rome

Collezione di tiramenti rari di celebrate statue antiche 1755

[Rome, circa 1755–1765]

folio (585 × 445 mm), (46) ff., comprising (1) calligraphic title (transcribed above), (2) calligraphic ‘Catalogo dei tiramenti’, written in two columns (44 items), (3–46) 44 drawings (each circa 515 × 345 mm), executed in pencil and grey chalk (except nos. 42–44, in pencil and red chalk), of which three signed by Mosman (nos. 13, 28, 33), numbered by a later hand in brown ink at bottom of each sheet. All sheets are laid to album leaves of brown wove paper.

provenance Elizabeth Katharine Theresa Hickes (1846–1923), daughter of Charles Robert Hickes (d. 1894), Barrister of the Middle Temple, and granddaughter of Charles Hickes frcs (1762–1840), physician of Bath, ‘Beckford’s doctor’1 — Bath Public Reference Library, printed exlibris, annotated in ink: [Presented by] Miss K. Hickes | 1925; librarian’s inscription on pastedown: Access. No. 26287 | Clas 732 (743) | Loc. Print case. Library blind stamp in blank area of each sheet — Bonhams, ‘Fine Books and Manuscripts’, London, 24 June 2015, lot 111

Occasional light foxing; old lateral fold (sheet 31).

binding English morocco binding of circa 1870, elaborately decorated in gilt, gilt catches and clasps (key missing), page edges gilt.

A series of drawings of the most beautiful and famous statues in Rome, created by a Franco-German artist, perhaps for an English patron, or with a view toward eventual publication in England, since the draughtsman has supplied a scale calibrated in both English piedi and Roman palmi. Nicolas Mosman (variously Nicolaus Mosman, Nikolaus Mosmann, Nicola Mosman) is known chiefly for a long series of drawings reproducing celebrated paintings (and some sculpture) in Roman collections, which he produced between 1764 and 1787 for Brownlow Cecil, 9th Earl of Exeter.2 Those drawings are said to have been intended for a ‘reference book of 250 paintings by Italian masters planned by Lord Exeter’.3 Our drawings of exemplary statues perhaps were made for a related project, a volume of ancient and modern sculpture for the edification of Englishmen of taste; or they might be souvenirs of a Roman sojourn, commissioned by another English tourist, or ‘paper tools’ made for commercial transactions of Rome-based dealers.4 Since all the drawings depict the complete statue, rather than details, and are highly finished, it is less likely that they are study sheets, derived from a sketchbook of Mosman.

There are forty-four drawings in the album, of which forty-one were executed by Mosman in pencil and black chalk (his preferred medium in the Exeter albums), and three in red chalk. The drawings are of near-uniform size (482/525 × 345/360 mm); each is enclosed by a ruled frame, most have a caption and scale beneath. Three drawings are signed by Mosman in pencil (nos. 13, 28, 33). The drawings were mounted on album leaves in the nineteenth century, when a title-leaf (Fig. 2) and a contents-leaf (Fig. 3) were supplied, and the sheets numbered sequentially in ink. The date ‘1755’ in the title perhaps was found on a portfolio that previously held the loose sheets; it could be the date of the earliest drawing, made soon after Mosman’s arrival in Rome.

In Rome, Mosman was linked socially and professionally with the painter Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779) and certain of his Germanic pupils, with the connoisseur Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), the painter-dealer Thomas Jenkins (c. 1722–1798), the architect-dealer James Byres of Tonley (1734–1817), and the restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (c. 1716–1779). The nexus of these relationships was possibly Mengs’ house in the Via Sistina (latterly in the Via Vittori, beneath the Spanish Steps), where Mengs operated a studio, school, and salon.

Although Mosman is presumed to have been a pupil of Mengs, evidence of that relationship has yet to emerge. He certainly was among the many artists clustered around Mengs and a frequent visitor to Mengs’ studio, since fourteen drawings in the series he produced for the Earl of Exeter reproduce paintings by Mengs, several recording an intermediate state of completion.5 A number of those paintings were owned by Thomas Jenkins, with whom Mosman was also in close contact. He drew two paintings by Jenkins himself and numerous paintings by Italian and other masters which passed through Jenkins’ hands, including his own portrait, painted by Mengs’ studio-manager, Anton von Maron (1733–1808).6 Remittances from Lord Exeter to Mosman sometimes were routed through Jenkins, who also dispatched Mosman’s drawings to England, and after Mosman’s death disbursed on behalf of Lord Exeter a pension paid to his widow.7

Jenkins first met Winckelmann about 1763. As the archaeologist was readying for publication his Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (published in 1764), Jenkins offered to help find a sponsor for its illustrations.8 Mosman probably was introduced to Winckelmann by Jenkins at this time. A relief in the Albani collection,9 where Winckelmann was librarian, was drawn and engraved by Mosman; intended originally for the title-page, it was deployed instead as a head-piece (Fig. 9; image).10 Mosman later drew for Winckelmann the famous bas-relief of Antinous which had been excavated in 1735 at Hadrian’s Villa, and taken afterwards to the Villa Albani; that drawing, engraved by Niccolò Mogalli, was utilised for Winckelmann’s Monumenti antichi inediti published in 1767 (Fig. 8; image).11 It is speculated that Mosman supplied drawings for numerous unsigned plates in the same book, and perhaps made drawings for the projected third volume.12

Although Mosman’s selection of antique statues is quite broad, it reflects the revaluation of Greco-Roman sculpture then being undertaken by Mengs and Winckelmann.13 Mosman does not limit himself to the traditional masterpieces concentrated in the Vatican Belvedere.14 Eleven drawings document recent additions to the Capitoline collection: five are of statues purchased 1733–1737 by Clement xii from the Albani and Odescalchi collections; six depict purchases made 1744–1753 by Benedict xiv from the D’Este collection, and from the digger-dealers Liborio Michilli and Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti.15 Other drawings record sculpture then within the Barberini,16 Borghese,17 Casali,18 Farnese,19 Giustiniani,20 Ludovisi,21 Medici,22 Pighini,23 Spada,24 and Verospi25 family collections. Two drawings are of modern sculptures: a bronze statue of Mercury by Guglielmo della Porta (c. 1500–1577), in the Palazzo Farnese (drawing 7); and a marble statue of Santa Susanna by Francois Duquesnoy (1597–1643), in the Roman church of S. Maria di Loreto (drawing 43).

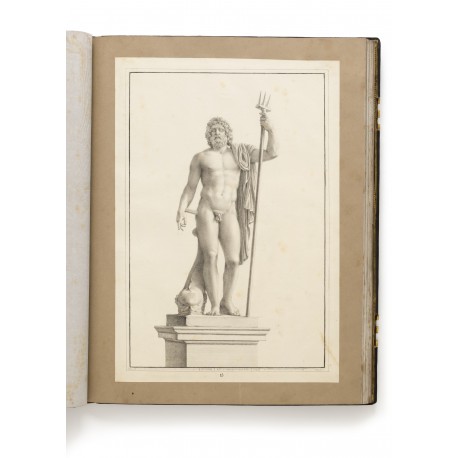

Four of Mosman’s drawings depict antique sculptures restored by Bartolomeo Cavaceppi. One (sheet 44; Fig. 4) represents the Faun of rosso antico discovered by Furietti in 1736, restored by Cavaceppi and Clemente Bianchi in 1744–1746, and in the latter year installed in the Capitoline Museum; the other three (drawings 8, 15, 20) depict restored sculptures introduced onto the market in 1754/1755, 1764, 1766/1768 respectively. The first of these (sheet 8, ‘Mercurio’; Fig. 5) records a statue purchased by Wilhelmine, Markgräfin von Bayreuth, in Rome, between 5 October 1754 and 9 August 1755; it potentially is the earliest drawing in our album.26 The second (sheet 15, ‘Nettuno di Cavaceppi’; Fig. 1) records a statue purchased in 1764 by Camillo Paderni for Carlos iii of Spain.27 The last (sheet 20, ‘Baccho di Cavaceppi’; Fig. 6) is of particular interest, as it records an intermediate stage in the restoration process: the headless torso, discovered in the Tiber about 1760, is already supplied with a head, but it still lacks both arms and the head of a snake, which were added before the sculpture entered the Prussian royal collection in 1766–1768.28

Five of the statues recorded by Mosman were not located in Rome.29 The sculptural group identified by Mosman as ‘Castor e Polluce in Spagna’ (sheet 34; Fig. 7) had been sold in 1724 by the Odescalchi to Philip v of Spain, and taken to La Granja de San Ildefonso. A plaster cast of the pair remained in Rome, in the French Academy, and Mosman may have drawn it (or another replica). Likewise, four statues identified in their captions as ‘di Firenze’ (drawings 6, 26, 39, 42) presumably are copies of the originals, all sent to Florence by the Medici about 1677, and installed in the Tribuna of the Uffizi. It may be no coincidence that Mengs owned plaster replicas of these four statues.30

About half of the statues drawn by Mosman had featured in Paolo Alessandro Maffei’s folio anthology of the most highly esteemed statues in Rome, published in 1704,31 however a careful comparison excludes the possibility that Mosman copied the prints. Other statues drawn by Mosman appear in Giovanni Gaetano Bottari’s illustrated catalogue of the Capitoline collection, published 1750–1755.32 Mosman’s viewpoints are again different, and it is obvious that he has not utilised Bottari’s work.

Nicolas Mosman

Nicolas Mosman was born at Haroué, Meurthe-et-Moselle (diocese of Toul), on 3 June 1729.33 According to depositions he gave in Rome in 1765 and 1775, he lived from 1745 until 1754 or 1755 in Vienna, associating there with the painters Anton von Maron and Christoph Unterberger (1732–1798). It could be that Mosman served his apprenticeship beside Maron, or studied in the Akademie der bildenden Künste with Unterberger. In the earlier deposition, Mosman stated ‘venni in Roma l’anno 1754, e non sono più partito’; in the latter, he declares that he remained in Vienna ‘fin a maggio 1755 che venni in Roma, da dove poi non sono più partito’.34 Since Maron and Unterberger are first recorded in Rome about this time, the three artists possibly travelled to Italy together.

At the time of their arrival in Rome, the studio in the Via Sistina of Anton Raphael Mengs was a magnet for young foreign artists. Anton von Maron soon became Mengs’ pupil and lodger, and in 1765 his brother-in-law.35 Although Mosman and Unterberger likewise befriended and fell under the influence of Mengs, it is not certain that they became pupils.36

Bas-relief of Antinous in the Villa Albani, drawn by Mosman and engraved by Niccolò Mogalli, for J.J. Winckelmann, Monumenti antichi inediti (Rome 1767), i, pl. 180 (image source)

Relief depicting Leto, Artemis and Apollo, drawn and engraved by Mosman, for J.J. Winckelmann, Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (Dresden 1764), p.ix (image source)

The copying of antique sculpture was then considered an essential part of the formation of an artist. The Accademia di San Luca held competitions for aspiring artists in which contestants were divided in three classes, those in the ‘Terza classa’ usually submitting finished drawings of a designated antique sculpture. The work selected in 1758 was ‘la statua del Gladiatore moribondo situate nel Museo Capitolino’; in the next competition, in 1762, it was ‘Amore e Psiche che sta nel Museo Capitolino’; in 1766, ‘il Gladiatore che combatte dell’eccellentissima Casa Borghese’; in 1771, ‘la statua d’Apollo di Villa Medici’; and in 1775, ‘la statua dell’Apollo di Belvedere’. All these sculptures were drawn by Mosman (sheets 25, 16, 24, 14, 33), however there is no evidence that he entered the competitions.37

By 1760, Mosman and Unterberger were sharing lodgings in the parish of S. Andrea delle Fratte, together with the Viennese painter Martin Knoller (1725–1804), and Friedrich Anders (c. 1734/1736– c. 1797) of Dresden, a former lodger in Mengs’ house.38 When in 1767 Mosman married Angela Balduzzi (Baldassi),39 he moved to via dei Greci in the parish of S. Lorenzo in Lucina. Old friendships were sustained: Maron witnessed the baptism of the first of Mosman’s seven children, Anna Maria; in 1768; both Maron and Mosman were witnesses at the wedding of Unterberger, in 1775.40

According to the sculptor Joseph Nollekens, Mosman and Brownlow Cecil, 9th Earl of Exeter (1725–1793) met for the first time in a Roman church, where Mosman ‘in the dress of a common soldier’ was ‘making a most elaborate drawing from one of the altar-pieces’.41 Nollekens does not date this meeting, however it must have occurred during the ninth Earl’s first visit to Rome, between 7 May and 5 June 1764;42 it could be that Mosman’s livelihood already was dependant on copying Old Masters for tourists. On 27 September 1764, the artist James Martin met Mosman in the Palazzo Barberini where he was ‘taking a Drawing of the famous Magdalen of Guido for Lord Exeter’.43 By 1772, Mosman was working primarily, if not exclusively for Lord Exeter.44

Lord Exeter had travelled to Italy with the intention of acquiring works of art to refurbish his seat in Lincolnshire. There was a strong tradition of collecting in the family and Burghley House was adorned by many important works of art, the majority acquisitions made in Italy by the fifth Earl.45 Among the paintings acquired in 1764, the most notable were Poussin’s Assumption of the Virgin (acquired from Niccolò Soderini via James Byres) and Gavin Hamilton’s Hebe (acquired direct from the painter). When Lord Exeter returned to Rome four years later (October 1768–April 1769), he was advised by both Jenkins and Byres, bought and commissioned more paintings, and ‘also acquired antique sculpture, a chimney-piece by Piranesi, and marble table tops, and he built up a fine collection of books and prints relating to Italy and the grand tour’.46

Few details can be gathered about Lord Exeter’s taste for sculpture and decoration.47 At the Richard Mead sale, in 1755, he had purchased for £136 10s the bronze head of Homer from the Arundel collection, which he presented a few years later to the British Museum,48 and a 1st–2nd century style alabaster draped female torso, referred to as the Empress Livia, wife of Augustus (Burghley House).49 On his initial visit to Italy, in 1764, he met in Rome the young sculptor Nollekens, then working in the studio of Cavaceppi, and dealing in antique sculpture, sometimes in partnership with Jenkins. Lord Exeter purchased at least two works from Nollekens: his copy of the Rondanini Medusa,50 and his Boy on a dolphin (copy of a Cavaceppi pastiche).51 An interest in antique sculpture is suggested by Lord Exeter’s acquisition of a black chalk drawing by Giovanni Battista Casanova of the Laocoon group in the Vatican.52 In Naples, he purchased three tables with tops inlaid with various sorts of lava from Mount Vesuvius (one was given in 1764 to the British Museum, the other two are at Burghley House).53

On his second visit to Italy, in 1768–1769, Lord Exeter acquired from uncertain sources a fragment of a wall painting with a head of Cupid in moulded stucco (later given to the British Museum),54 copies of two antique statues by Joseph Claus (fl. Rome 1754–1783),55 a copy of the Laocoon, an antique head of Niobe (later given to Lord Yarborough),56 and an antique statue of Bacchus.57 Further purchases were made from Nollekens: a Venus and Cupid riding a Dolphin, Daedalus and Icarus, Nollekens’ version of the Uffizi Niobe and her children, and several portrait busts.58 Byres and Jenkins supplied cameos by Johann Friedrich Reiffenstein (1719–1793),59 a chimney-piece with rosso antico panels by G.B. Piranesi,60 and important furniture, including tables with mosaic tops by Cesare Aguatti (active 1774–1780).61

In addition to drawings of paintings by Italian and other masters, Mosman produced black chalk drawings for Lord Exeter of antique and modern sculpture. Included in the aforementioned albums in the British Museum are fifteen drawings of sculpture: a mixture of famous statues,62 sculpture newly installed in the Capitoline Museum,63 a single bronze statue,64 and esoteric objects: a sardonyx cameo from the Strozzi collection,65 a bust of Clement xiv, by the Irish sculptor Christopher Hewetson, drawn in 1771 or 1772,66 and a ‘Statue of a faun sleeping, after the antique… From an antique Statue in the Possession of Sir Henry Mainwaring Bart.’67 Three drawings in the British Museum albums depict sculptures found in our album (Farnese Hercules, Farnese Flora, and Borghese Gladiator). The drawings of full-length statues are similar in size to those in our album; none of the British Museum drawings is inscribed with a scale.

Jenkins served as banker to Lord Exeter and was charged with disbursing Mosman’s salary.68 His oversight of Mosman evidently involved selecting works of art for reproduction. Although a capable draughtsman himself,69 Jenkins instructed Mosman to draw his own paintings,70 and to draw objects which he wished to sell to his clients. Among the Mosman drawings in the Exeter albums in the British Museum are some thirty sheets with inscriptions recording Jenkins as the owner (or seller) of the painting depicted (all of these drawings reproduce paintings).71 At later dates, Jenkins’ favoured draughtsmen for sculpture were the painter and picture restorer Friedrich Anders, Mosman’s former housemate in the Via Sistina (1760–1763), and then, in the 1780s, Vincenzo Dolcibene, whose style ‘gives more the character of the antique than any I have hitherto seen’.72

Mosman continued working for Jenkins and Lord Exeter until the end of his life. In September 1786, about a year before his death (12 August 1787), Jenkins dispatched to Lord Exeter ‘a Tin case with five drawings by Mr Mosman’,73 among them a copy of Tommaso Manzuoli’s ‘The Visitation’, an altarpiece which had been acquired by Jenkins in 1786, and was offered to Lord Exeter for £400. Although Mosman’s labour over twenty years had cost an enormous sum – £2000, Lord Exeter reckoned74 – the long series of his drawings was presented by Lord Exeter to the British Museum, on 2 January 1789. If Lord Exeter had once intended to capitalise on his investment by producing a set of engravings from Mosman’s drawings, the project never came to fruition.

Apart from Lord Exeter, Mosman is known to have produced drawings for one other individual: John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute (1713–1792). On his second visit to Rome, in March 1769, Lord Exeter found himself in the company of Lord Bute, and agreed that Mosman should copy for him two engraved gems by Giovanni Pichler, ‘the Agrippina and Gypsy’.75 The transaction involved Jenkins’ rival, James Byres, and Mosman’s drawings were delivered after long delay (probably engineered by Jenkins, to stall Byres’ business dealings). Three years later, Byres lamented to Lord Exeter that Mosman ‘has done nothing for me since the two figures You gave him have to do for Lord Bute’.76

It is possible that drawings by Mosman can be discovered among the many anonymous sheets in the Townley collection at the British Museum. Four unattributed drawings in that collection executed in black chalk have Mosman’s characteristic framing lines.77 The drawings depict portrait busts or marble heads which had entered the Capitoline museum with the purchase of the Albani collection, in 1733 (B131, B147, B149, C15); numerous objects of this provenance were drawn by Mosman. Charles Townley (1737–1805) made the first visit of his three visits to Italy in 1768 and there began to assemble drawings of sculpture for comparison with objects in his own collection. Jenkins acted as his agent for over thirty years and is the likely supplier of these four drawings.

Bibliography

Amelung (1903–1908)

Walther Amelung, Die Sculpturen des Vaticanischen Museums (Berlin 1903–1908)

Bober & Rubinstein (1986)

Phyllis Pray Bober and Ruth Rubinstein, Renaissance artists & antique sculpture: a handbook of sources (London & Oxford 1986)

Bottari (1750)

Giovanni Gaetano Bottari, Musei Capitolini Tomus Primus (Rome 1750)

Bottari (1755)

Giovanni Gaetano Bottari, Musei Capitolini Tomus Tertius continens Deorum simulacra aliaque signa cum animadversionibus (Rome 1755)

Catalogo del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (1989)

Le collezioni del Museo Nazionale di Napoli, [2]: La scultura greco-romana, le sculture antiche della collezione Farnese, le collezione monetali, le oreficerie, la collezione glittica, edited by Renata Cantilena (Rome & Milan 1989)

Cavaceppi (1768)

Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, Raccolta d’antiche statue busti bassirilievi ed altre sculture restaurate da Bartolomeo Cavaceppi scultore romano. Volume primo (Rome 1768)

Coen (2018)

Paolo Coen, ‘Copie a disegno da pezzi classici sul mercato romano del diciottesimo secolo: un nuovo album di Nicolas Mosman e una proposta per Bartolomeo Cavaceppi’ in Libri e album di disegni 1550–1800, edited by Vita Segreto (Rome: De Luca, 2018), pp.189–202 (Figs. 8, 11–18 reproduce drawings in our album)

Coen (2019)

Paolo Coen, 'Brownlow Cecil, Ninth Earl of Exeter, Thomas Jenkins and Nicolas Mosman: Origins, functions and aesthetic guidelines of a great drawing collection in eighteenth-century Rome, now at the British Museum’ in The Art Market in Rome in the eighteenth century: A Study in the social history of art, edited by Paolo Coen (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp.146–186 (mention of our album on pp.146, 163)

Coen (2020)

Paolo Coen, ‘Le marché des dessins d'après l'antique à Rome au XVIIIe siècle’ in Une histoire en images de la collection Borghèse: les antiques de Scipion dans les albums Topham, edited by Marie-Lou Fabréga-Dubert (Paris: Mare et Martin / Louvre éditions, 2020), pp.48–67 (Fig. 18 reproduces a drawing in our album)

Fendt (2012)

Astrid Fendt, Archäologie und Restaurierung: die Skulpturenergänzungen in der Berliner Antikensammlung des 19. Jahrhunderts (Berlin 2012)

Gasparri (2007)

Le sculture farnese: storia e documenti, edited by Carlo Gasparri (Naples 2007)

Gori (1734)

Anton Francesco Gori, Statuae antiquae in Thesauro Mediceo (Florence 1734)

Haskell & Penny (1981)

Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: the Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (New Haven & London 1981)

Kalveram (1995)

Katrin Kalveram, Die Antikensammlung des Kardinals Scipione Borghese (Worms 1995)

Maffei (1704)

Paolo Alessandro Maffei, Raccolta di statue antiche e moderne (Rome 1704)

Magnan

Dominique Magnan, Elegantiores Statuae Antiquae (Rome 1776)

Mansuelli (1958–1961)

Guido A. Mansuelli, Galleria degli Uffizi. Le sculture (Roma 1958–1961)

Michel (1996)

Olivier Michel, Vivre et peindre à Rome au XVIIIe siècle, Collection de l’Ecole française de Rome, 217 (Rome 1996)

Roettgen (1993)

Steffi Roettgen, Anton Raphael Mengs, 1728–1779, and his British patrons, catalogue of exhibition held at the Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood, 16 June–12 September 1993 (London 1993)

Stuart Jones (1912)

Henry Stuart Jones, A catalogue of the ancient sculptures preserved in the municipal collections of Rome. [Vol.1] The sculptures of the Museo Capitolino (Oxford 1912)

Valeriani (1998)

Roberto Valeriani, ‘Reiffenstein, Piranesi e i fornitori romani del Conte di Exeter’ in Antologia di Belle Arti: Studi sul Settecento [1], nos. 55–58 (1998), pp.145–154

Winckelmann (1756)

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Schriften und Nachlass: Bd. 5,1: Ville e palazzi di Roma: Antiken in den römischen Sammlungen: Text und Kommentar, by Sascha Kansteiner, Brigitte Kuhn-Forte and Max Kunze (Mainz 2003)

List of drawings

Numbered 1

Roman marble statue of Isis, 117–138 ad, 180 cm. Discovered at Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli; documented in the possession of Girolamo Lotteri, by 1704; ex-Villa Albani, Rome; purchased in 1733 by Clement xii for the Capitoline Museum (Albani Inventory, C25). Winckelmann (1756), p.316 (91, 16–17)

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 744 (image, image). Stuart Jones (1912), p.354 no. 15 (pl. 88)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 143 (plate legend Statva d’Iside in casa di Girolamo Lotteri; image); Bottari (1755), pl. 73 (image)

Numbered 2

Roman marble copy of a Greek statue of Pallas Athena, 138–193 ad, 228 cm. Ex-Giustiniani collection, Rome; bought by Lucien Bonaparte c. 1804. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.269–271 no. 63. Laura Buccino, ‘Statua di Athena da un originale tardoclassico, cosiddetta Minerva Giustiniani’ in I Giustiniani e l’antico, catalogue of an exhibition held at Palazzo Fontana di Trevi, Rome, 26 October 2001–27 January 2002, edited by Giulia Fusconi (Rome 2001), pp.183–186. Winckelmann (1756), p.354 (120, 23–32)

Present location: Rome, Musei Vaticani, Braccio Nuovo Nr. 111, Inv. no. 2223 (image). Amelung (1903–1908), i, pp.138–143 no. 114

Mosman’s drawing depicts four fingers on the hand holding the shawl.

Reproduced in Galleria Giustiniana del Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani (Rome 1631-1637), pl. 3 (image); François Perrier, Icones et segmenta nobilium signorum et statuarum quæ Romæ extant, delineata atque in ære inciso (Paris 1638), pl. 54 (image)

Numbered 3

Roman marble statue of Jupiter Tonans. Friedrich Matz, Antike bildwerke in Rom mit Ausschluss der grösseren Sammlungen, edited by Friedrich Karl von Duhn (Leipzig 1881), i, p.3. Angela Gallottini, Le sculture della collezione Giustiniani (Rome 1998), i, p.115 no. 1707 (1638 inventory); p.202 no. 56 (1684 inventory, then situated in the garden of S. Giovanni in Laterano: ‘una statua antica di un Giove antico ristorata alta palmi quindeci incirca’); p.258 no. 738 (1793 inventory, by Vincenzo Pacetti: ‘Nell’arcone in mezzo detta prospettiva vi è collocata sopra piedistallo una statua colossale, rapp.te un Giove con il braccio destro alzato, tenendo nella mano il fulmine ed il braccio sinistro posato sul fianco, metà panneggiato e metà nuda’). Winckelmann (1756), p.211 (22, 26–27)

Location unknown; perhaps the statue (330 cm) offered by Robilant+Voena / Il Quadrifoglio at the Biennale internazionale di Antiquariato di Roma, Palazzo Venezia, 1–6 October 2014 (image, image)

Reproduced in Galleria Giustiniana del Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani (Rome 1631–1637), pl. 105 (image)

Numbered 4

Roman marble copy of a Greek statue of Jupiter, 200–300 ad, 230 cm. Ex-Palazzo Verospi, Rome (c. 1680–1771); bought in December 1771 for Clement xiv. Pierluigi Lotti, ‘Alcune note su Palazzo Verospi’ in Alma Roma 3 (September–December 2000), pp.201–232 (p.214)

Present location: Rome, Musei Vaticani, Inv. no. 671 (image). Amelung (1903–1908), ii, pp.519–520 no. 326 (pl. 73)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 135 (image)

Numbered 5

Marble statue also known as ‘Afrodite Callipige’, a restored copy of a Hellenistic original, 1st century bc, 152 cm. Ex-Farnese collection, Rome (acquired c. 1593); moved by the Bourbons from Rome to Naples c. 1792. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.316–318 no. 83.Gasparri (2007), p.162 no. 12 (‘Catalogo dei disegni e delle stampe delle sculture della collezione farnese’). Winckelmann (1756), pp.280–281 (67, 225)

Present location: Naples, Museo Nazionale, Inv. no. 6020 (image). Catalogo del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (1989), p.156 no. 18

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 55 (plate legend Venere uscita dal bagno in atto d’asciugarsi Nel Palazzo Farnese; image)

Numbered 6

Marble statue known as the ‘Venus de’ Medici’, perhaps Athenian and of the 1st century bc, 153 cm. Ex-Villa Medici, Rome; sent to Florence in 1677, by 1688 placed in the Tribuna of the Uffizi. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.325–328 no. 88

Present location: Florence, Uffizi, Tribuna, Inv. no. 224 (image). Mansuelli (1958–1961), i, pp.69–74 no. 45 (pls. 45a-e)

Mosman probably has drawn a plaster cast of the original marble.

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 27 (image); Gori (1734), iii, pl. 26 (image); compare Cavaceppi (1768), i, pl. 36 (copy supplied to Thomas Anson; image)

Numbered 7

Mosman’s drawing documents the lost bronze replica by Guglielmo della Porta of the ‘Mercurio de Belvedere’, an antique marble statue of a youth (155 cm) to which attributes of Mercury had been added during the Renaissance (Haskell & Penny, 1981, pp.266–267 no. 61). After the marble statue was transferred from the courtyard of the Belvedere to Florence, about 1560, it attracted little attention, and Della Porta’s bronze cast became more famous. Displayed in the ‘sala de’ Filosofi’ of the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, from 1575, the bronze can be traced through successive Farnese inventories until early in the 19th century (Bertrand Jestaz, ‘Copies d’antiques au palais Farnèse: Les fontes de Guglielmo Della Porta’ in Mélanges de l’Ecole française de Rome: Italie et Méditerranée 105, 1993, pp.7–48, esp. pp.19–21). Winckelmann (1756), p.278 (66, 20–21)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 57 (plate legend Statva di bronzo di Mercvrio col pileolo alato, e con foglio nella sinistra, per la rappresentanza che hà d’esser messaggiero delli dei … Nel Palazzo Farnese; image, image)

Numbered 8

Roman marble headless statue, completed with an antique head, 2nd century ad, 153.5 cm. Found at an unknown date; restored by Bartolomeo Cavaceppi before 1754/1755. Purchased in Rome in 1755 from Cavaceppi (or intermediary) by Wilhelmine, Markgräfin von Bayreuth (1709–1758). Fendt (2012), ii, pp.128–132 no. 28

Present location: Berlin, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen, 531 (image). Saskia Hüneke, Bestandskataloge der Kunstsammlungen Skulpturen: Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin Brandenburg. Antiken I: Kurfürstliche und Königliche Erwerbungen für die Schlösser und Gärten in Brandenburg-Preussen vom 17. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (Berlin 2009), p.362 no. 224

Reproduced by Cavaceppi (1768), pl. 14 (plate legend Mercurio | Or esistente in Germania; image)

Numbered 9

Roman marble statue of Artemis with a hound, from a Greek original, 194 cm. Ex-Villa D’Este, Tivoli (inventory of 1572, no. 27); bought by Benedict xiv in 1753, and presented to the Capitoline Museum. Bottari states that it came from Tivoli as a mezza figura; the head does not belong to the statue.

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 62 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.44–45 no. 52 (pl. 6)

Reproduced by Bottari (1755), pl. 72 (image)

Numbered 10

Roman marble statue of Harpocrates, 117–138 ad, 158 cm. Found by Liborio Michilli at Hadrian’s Villa in 1741; presented by Benedict xiv in 1744 to the Capitoline Museum. Winckelmann (1756), p.374 (133, 9–10)

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 646 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.292–293 no. 28 (pl. 71)

Reproduced by Bottari (1755), pl. 74 (image)

Numbered 11

‘Juno Cesi’, a copy of a Pergamene statue, 175–150 bc, 228 cm. Ex-Cesi collection (from 1530s, described by Aldrovandi in 1556 as ‘una donna Amazona vestita’); ex-Villa Albani, Rome; purchased in 1733 by Clement XII for the Capitoline Museum (Albani Inventory, D1). Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.242–243 no. 51. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), pp.55–56 no. 8. Carlo Pietrangeli, ‘Le antichità dei Cesi in Campidoglio’ in Bollettino dei Musei Comunali di Roma 3 (1989), pp.51–63 (p.58 and fig. 4)

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 731 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.340–341 no. 2 (pl. 85)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 129 (reversed by the engraver; image); Bottari (1755), pl. 8 (image)

Numbered 12

Roman statue of porphyry, marble, and verde antico, known as ‘Iuno regina’ or ‘Orante Borghese’, c. 100–200 ad, 204 cm. Ex-Borghese collections (from c. 1610–1808). Kalveram (1995), pp.198–199 no. 76. Winckelmann (1756), p.185 (8, 20–21)

The head was replaced in 1780 by the restorer Vincenzo Pacetti.

Present location: Paris, Musée du Louvre, Salle A du Manège, Inv. MA 2228 (image). Jean Charbonneaux, La sculpture grecque et romaine au Musée du Louvre (Paris 1963), p.101 no. 2226

Reproduced by François Perrier, Segmenta nobilium Signorum et Statuarum, Quae temporis dentem invidium evasere (Rome 1638), pl. 56 (image); Bernard de Montfaucon, L’Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures (Paris 1722), i, pl. 21 (image); Jean Barbault, Recueil des divers monumens anciens (Roma 1770), pl. 66 (image)

Numbered 13

Roman marble copy made in the early 3rd century ad, signed: Glykon Athenaios epoiei (made by Glycon of Athens), from an original by Lysippos, 317 cm. Ex-Palazzo Farnese, Rome (c. 1546–ante 1787). Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.229–232 no. 46. Winckelmann (1756), p.275 (64, 6–16). Gasparri (2007), pp.160–162 no. 7 (‘Catalogo dei disegni e delle stampe delle sculture della collezione farnese’)

Present location: Naples, Museo Nazionale, Inv. no. 6001 (image). Catalogo del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (1989), pp.154–155 no. 10

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 49 (image)

Numbered 14

The ‘Medici Apollo’, a Roman copy of a Hellenistic sculpture, 141 cm. Ex-Villa Medici, Rome; taken to Florence in 1769–1770. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.146–148 no. 7. Winckelmann (1756), p.299 (81, 32–82, 2)

Present location: Florence, Uffizi, Tribuna, Inv. no. 229 (image). Mansuelli (Rome 1958–1961), i, pp.74–76 no. 46 (pls. 46a-b)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 39 (plate legend Apollo ignudo, e con la faretra legata ad un tronco. Negl’orti Medicei; image)

Numbered 15

Roman marble statue of Neptune, c. 130–140 ad, 236 cm. According to Winckelmann, writing in 1764, this ‘large and beautiful statue of Neptune… was found at Corinth in Greece a few years ago and is now for sale in Rome’ (J.J. Winckelmann, History of the art of antiquity, translated by H.F. Mallgrave, edited by Alex Potts, Los Angeles 2006, p.329). The marble was purchased in 1764 by Camillo Paderni, agent of Carlos iii of Spain; see María del Carmen Alonso Rodríguez, ‘La colección de antigüedades comprada por Camillo Paderni en Roma para el rey Carlos iii’ in Illuminismo e ilustración: le antichità e i loro protagonisti in Spagna e in Italia nel xviii secolo, edited by Betrice Cacciotti (Rome 2003), pp.29–46 (p.36); Fernández-Miranda y Lozana, Inventarios reales: Carlos iii, 1789–1790 (Madrid 1988), i, p.95 no. 921

Present location: Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, E-3. Stephan F. Schröder, Catálogo de la escultura clásica del Museo del Prado (Madrid 2004), ii, pp.417–423 no. 193.

Mosman locates this statue in the studio of the restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi.

Roman marble statue of Eros and Psyche, a copy of the 2nd century ad from a Greek original, 125 cm. Reputedly found on the Aventine Hill near S. Balbina in February 1749; given by Benedict xiv to the Capitoline Museum in that year. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.189–191 no. 26

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 408 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.185–186 no. 3 (pl. 45)

Reproduced by Bottari (1755), pl. 22 (image)

Numbered 17

Roman marble statue of Eros stringing his bow, a copy of a Greek original of the 4th century bc, 123 cm. Ex-Villa d’Este, Tivoli (inventory 1572, no. 55); bought by Benedict xiv in 1753 for the Capitoline Museum. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), pp.88–89 no. 50

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 410 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.87–88 no. 5 (pl. 18)

Reproduced by Bottari (1755), pl. 24 (image)

Numbered 18

Roman marble statue of a girl with a crown of roses, perhaps a copy of a Hellenistic bronze, 168 cm. Found in 1744 by Liborio Michilli at Hadrian’s Villa; presented by Benedict xiv to the Capitoline Museum.

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 743 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), p.353 no. 14 (pl. 87)

Compare Giovanni Domenico Campiglia’s drawing for Bottari (Rome, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Fondo Corsini, Inv. no. 128084;image)

Reproduced by Bottari (1755), pl. 45 (image); Magnan (1776), pl. 33 (image)

Numbered 19

‘Mars in Repose’, known as the ‘Marte Ludovisi’, or ‘Ares Ludovisi’, 138–193 ad, 156 cm. Ex-Ludovisi collections (1622–1901); acquired in 1901 by the Italian State, exhibited until 1997 in the Museo delle Terme, Rome. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.260–262 no. 58. Winckelmann (1756), p.343 (111, 6–17)

Present location: Roma, Palazzo Altemps, Inv. no. 8602 (image). Museo Nazionale Romano. Le Sculture [I/5], I marmi Ludovisi, compiled by Beatrice Palma and Lucilla de Lachenal (Rome 1983), pp.115–121 no. 51; Scultura antica in Palazzo Altemps, edited by Matilde De Angelis d’Ossat (Milan 2002), pp.161–165

This drawing is erroneously entered in the album’s ‘Catalogo dei Tiramenti’ as ‘Marte – in Villa Casale’. The Cupid seated by the figure’s foot (added by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, in 1622) is excluded from the two prints of the statue (by Charles Randon) published in Maffei’s anthology.

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pls. 66–67 (image, image)

Numbered 20

Roman marble torso of Agathodaemon restored with an unrelated head, as ‘Antinous Agathodaemon’, 130–138 ad. The torso reputedly was found in the Tiber in 1760 (head found separately); purchased from Giovanni Lodovico Bianconi in 1766–1768 for the Prussian royal collections. Konrad Levezow, Ueber den Antinous dargestellt in den kunstdenkmaelern des alterthums (Berlin 1808), pp.82–84

Present location: Berlin, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen, Sk 361(image). Fendt (2012), ii, pp.166–171 no. 35.

Mosman’s drawing evidently was made in Bartolomeo Cavaceppi’s studio, during restoration: the statue is already supplied with a head; both arms and the head of the snake were added before it was sold. The restored statue was one of twenty-two purchased in 1766–1768 for the Prussian royal collections (nine of the group were restorations by Cavaceppi).

Reproduced by Cavaceppi (1768), pl. 24 (plate legend Antinoo | D’eccellente scultura alto palmi undici e mezzo | Or esistente in Germania | presso Sua Maestà Prussiana; image; also shown on thefrontispiece)

Numbered 21

Marble statue of Antinous as Dionysos, known as the ‘Antinous Casali’, 117–138 ad, 235 cm. Found between 1698–1704 in the Garden of the Villa Casali on the Caelian Hill in Rome; sold by that family c. 1884–1888; in 1903 bought for the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Rita Santolini Giordani, Antichità Casali: la collezione di Villa Casali a Roma (Rome 1989), p.44 no. 22; p.97. Winckelmann (1756), p.244 (42, 1)

Present location: Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Inv. no. 960 (image). Flemming Johansen, Catalogue Roman Portraits (Copenhagen 1995), ii, pp.122–125 no. 46.

This statue was greatly admired by Winckelmann, who counted it among the most important sights of Rome (Mette Moltesen and Rebecca Hast, ‘The Antinous Casali in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek’ in Analecta Romana Instituti Danici 30, 2004, pp.101–117).

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 138 (plate legend Statua di Bacco, trouata trà le rouine dell’Antico Macello d’Augusto nel Monte Celio. Negl’Orti Casali a S. Stefano Rotondo; image)

Numbered 22

Marble statue of Hermes, known as the ‘Belvedere Antinous’, 117–138 ad, 195 cm. Discovered near Castel S. Angelo in 1543; purchased from Nicolaus de Palis, and installed before 1545 in the Vatican sculpture court. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.141–143 no. 4. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), p.58 no. 10. Winckelmann (1756), p.173 (3, 6–7)

Present location: Rome, Musei Vaticani, Cortile Ottagono, Inv. no. 907 (image). Amelung (1903–1908), ii, pp.132–138 no. 53 (pl. 12)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 3 (reversed by the engraver; image); Magnan (1776), pl. 6 (genitals now covered; image)

Numbered 23

Roman marble statue of Antinous as Hermes, a copy of a Greek original (early 4th century bc), 180 cm. Reputedly found at Hadrian’s Villa; ex-Villa Albani, Rome; restored by Pietro Bracci before 1733; purchased in 1733 by Clement xii for the Capitoline Museum (Albani Inventory, D8). Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.143–144 no. 5

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 741 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.351–352 no. 12 (pl. 87)

Compare Giovanni Domenico Campiglia’s drawing for Bottari (Rome, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Fondo Corsini, Inv. no. 128094; image).

Reproduced by Bottari (1755), pl. 56 (image); Magnan (1776), pl. 30 (image)

Numbered 24

Hellenistic marble statue of a warrior, inscribed: Agasias Dositeou Efesios epoiei, c. 100–90 bc, length 199 cm. Ex-Villa Borghese, Rome (from 1613); sold in 1807 to Napoleon Bonaparte. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.221–224 no. 43. Kalveram (1995), pp.208–210 no. 94. Winckelmann (1756), p.181 (6, 20–25)

Present location: Paris, Musée du Louvre, Inv. MA 527 (image). Jean Charbonneaux, La sculpture grecque et romaine au Musée du Louvre (Paris 1963), p.71.

Reproduced by François Perrier, Segmenta nobilium Signorum et Statuarum, Quae temporis dentem invidium evasere (Rome 1638), pls. 26–28 (image); Maffei (1704), pls. 75–76 (image, image)

Numbered 25

Roman marble statue of a ‘Dying gladiator’ (Galata Morente), height 93 cm. Ex-Ludovisi collection, Rome; by 1693, in the possession of Livio Odescalchi; acquired before 1737 by Clement xii for the Capitoline Museum. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.224–227 no. 44. Winckelmann (1756), p.394 (151, 9–11)

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 747 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.338–340 no. 1 (pl. 85)

Compare Giovanni Domenico Campiglia’s drawings in Rome, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Fondo Corsini, Inv. nos. 128103–128104 (image, image) and London, British Museum, 1865,0114.821 (image)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 65 (image); Bottari (1755), pl. 67 (image)

Comparative illustration

Maffei (1704), pl. 65

(image source)

Numbered 26

Marble group, known as ‘The Wrestlers’, ‘Gruppo di Lottatori’, ‘Luctatores’, or ‘Pancratiastae’, 27–98 ad, 89 cm. Ex-Villa Medici, Rome (from its discovery in 1583); sent to Florence in 1677, and by 1688 placed in the Tribuna of the Uffizi. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.337–339 no. 94

Present location: Florence, Uffizi, Tribuna, Inv. no. 216 (image). Mansuelli (1958–1961), i, pp.92–94 no. 61 (fig. 62)

Mosman most probably has drawn a plaster cast of the original marble.

Reproduced by François Perrier, Segmenta nobilium Signorum et Statuarum, Quae temporis dentem invidium evasere (Rome 1638), pls. 35–36; Maffei (1704), pl. 29 (image); Gori (1734), iii, pls. 73–74 (image, image)

Numbered 27

‘The Hermaphrodite’, Roman marble copy of a bronze original, c. 100–150 ad, length 147 cm. Ex-Borghese collections, Rome (from c. 1625); sold to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.234–236 no. 48. Kalveram (1995), pp.231–233 no. 134. Winckelmann (1756), pp.190–191 (11, 27)

Present location: Paris, Musée du Louvre, Salle des Caryatides, Inv. MA 231 (image). Jean Charbonneaux, La sculpture grecque et romaine au Musée du Louvre (Paris 1963), pp.77–78

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 78 (image)

Numbered 28

Marble statue of Ariadne sleeping (‘L'Arianna addormentata, cosiddetta Cleopatra’), a Roman Hadrianic copy after a Hellenistic original of c. 200 bc

The location of the statue is not stated. Although there are slight disagreements in pose, support, and arrangement of the drapery, Mosman seems to be recording the Ariadne placed in the Belvedere by Julius ii in 1512 (Museo Pio Clementino, Galleria delle Statue, Inv. no. 548; image). In Mosman’s view, water has ceased to flow beneath Ariadne’s feet (compare Giovan Battista de Poilly’s print, published by Maffei in 1704; image), however other grotto references are maintained. By 1782, the statue had been transferred to the new Galleria delle Statue in the Museo Pio-Clementino, and given a new support (compare Lorenzo Roccheggiani’s drawing engraved by Francesco Piranesi, in 1781; image).

Other versions of ‘Sleeping Ariadne’ correspond to lesser degrees: the one displayed in the Villa Medici in Rome until 1787 (now Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi; image) significantly alters the placement of her head; another version formerly displayed in the Villa Borghese (now Paris, Musée du Louvre; image) is reversed in direction, and has a completely covered upper body; and a third version (now Madrid, Prado; image) has a different arrangement of drapery, and no veil covering her head. Clelia Laviosa, ‘L’Arianna addormentata del Museo Archeologico di Firenze’ in Archeologia Classica 10 (1958), pp.164–171 (list of replicas). Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.184–187 no. 24. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), pp.113–114 no. 79. Carlo Gasparri, ‘Statua di Arianna dormiente’ in Villa Medici. Il sogno di un cardinale. Collezioni e artisti di Ferdinando de’ Medici, edited by Michel Hochmann (Rome 1999), pp.168–171 no. 18

Compare Maffei (1704), pl. 8 (image; image)

Numbered 29

Marble statue, 1st century bc, signed by Apollonios, 159 cm. Located in the Belvedere, Rome, from c. 1506. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.311–314 no. 80. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), pp.166–168 no. 132

Present location: Rome, Musei Vaticani, Sala delle Muse, Inv. no. 1192 (image). Amelung (1903–1908), ii, pp.9–20 no. 3 (pl. 2)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 9 (image)

Numbered 30

Roman Marble group known as the ‘Fable of Dirce’, ‘Zetus et Amphion’, or ‘Toro Farnese’, early 3rd century ad, 370 cm. Installed in the Palazzo Farnese, Rome, in 1546; taken to Naples in 1788. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.165–167 no. 15. Catalogo del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (1989), p.154 no. 11. Christian Kunze, ‘Dall’originale greco alla copia romana’ in Il Toro Farnese: la ‘montagna di marmo’ tra Roma e Napoli, edited by Enrica Pozzi (Naples 1991), pp.13–42. Winckelmann (1756), p.285 (69, 22–70,6). Gasparri (2007), p.162 no. 8 (‘Catalogo dei disegni e delle stampe delle sculture della collezione farnese’)

Present location: Naples, Museo Nazionale, Inv. no. 6002 (image)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 48 (image)

Numbered 31

Marble group, c. 40–20 bc, 242 cm. Installed in a court yard of the Belvedere, Rome, in 1506. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.243–247 no. 52. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), pp.152–155 no. 122

Present location: Rome, Musei Vaticani, Cortile Ottagono, Inv. no. 1039 (image)

In Claude Randon’s print (Maffei 1704, pl. 1) the right arm of the dying younger son is shown broken. In 1725–1727 Agostino Cornacchini restored the group, extending the right arm upwards; Mosman, however, depicts the gesture of the younger son as it appeared prior to Cornacchini’s intervention. In this he follows two casts of the Laocoon commissioned c. 1750–1770 by Anton Raphael Mengs, one of which is now in Florence, the other in Dresden (Die Sammlung der Gisabgüsse von Anton Raphael Mengs in Dresden, edited by Moritz Kiderlen, Dresden 2006, p.95, table 6 no. xxiii; image; Orietta Rossi Pinelli, ‘The Surgery of Memory: Ancient Sculpture and Historical Restorations’ in Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage, Los Angeles 1996, p.292).

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 1 (reversed by the engraver; image); cf. J.J. Winckelmann, Storia delle arti del disegno presso gli antichi, edited by Carlo Fea (Rome 1783–1784), ii, pl. 4 (showing Cornacchini’s restoration; image)

Numbered 32

Marble statue, perhaps a replica of a Pergamene bronze, 250–200 bc, 215 cm. Found in the 1620s in the moat below Castel Sant’ Angelo during excavations sponsored by Urban viii; ex-Barberini family collections, Rome; acquired in 1813 by Ludwig of Bavaria (arrived in Munich in 1820). Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.202–205 no. 33. Winckelmann (1756), p.306 (87, 4–5)

Present location: Munich, Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Inv. no. 218 (image)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 94 (image)

Numbered 33

Roman marble statue of Apollo, a copy of a lost Hellenistic bronze, 130–140 ad, 224 cm. Discovered in the 1490s in the garden of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere at S. Pietro in Vincoli; placed in the Belvedere by 1511. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.148–151 no. 8. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), pp.71–72 no. 28

Present location: Rome, Musei Vaticani, Cortile Ottagono, Inv. no. 1015 (image). Amelung (1903–1908), ii, pp.256–269 no. 92 (pl. 12)

Although uncaptioned, Mosman appear to record here the Apollo of the Belvedere.

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 2

Numbered 34

Marble group of Orestes and Pylades, also known as the ‘Gruppo di San Ildefonso’, c. 0–50 ad, 158 cm. Ex-Ludovisi, Massimi, Azzolini, Odescalchi family collections; sold in 1724 to Philip v of Spain. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.173–177 no. 19

Present location: Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, Inv. 28-E (image). Stephan F. Schröder, Catálogo de la escultura clásica del Museo del Prado (Madrid 2004), ii, pp.367–374 no. 181

It is possible that Mosman is documenting the cast of this group made between 1687 and 1706 and kept in the French Academy in Rome, after the original went to Spain. Mosman does not reproduce the print by Nicolas Dorigny published by Maffei (1704) pl. 121 (image; copy in Bernard de Montfaucon, Supplément au livre de l'Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures, Paris 1724, i, p.208, pl. 76, image); nor the anonymous print in J.J. Winckelmann, Monumenti antichi inediti (Roma 1767), p.xiv (image).

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 121 (image)

Numbered 35

Roman marble statue of a writer in a toga, known as ‘Marius’, 189 cm. Apparently acquired by Pius iv from Tommaso della Porta in 1565; among the first statues placed in the Capitoline Museum (in the Stanza dei Filosofi by 1687; removed by Clement xii, and placed in the Salone). Winckelmann (1756), pp.373–374 (133, 1–3)

Current location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 635 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), p.284 no. 14 (pl. 69)

Reproduced by Girolamo Franzini, Icones Statuarum Antiquarum Urbis Romae (Rome 1589), as ‘C. Marius’ (image); Bottari (1755), pl. 50 (image)

Numbered 36

Roman marble statue of Pompey the Great, its head replaced in the 16th century, c. 68–98 ad, 300 cm. Excavated 1552–1553 in Via dei Leutari, Rome; reputedly presented by Julius III to Cardinal Capodiffero, and placed in Palazzo Capodiffero (as from 1632, Palazzo Spada). Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.296–300 no. 73. Marina Sapelli, ‘Restauro della statua di ‘Pompeo’ in Bollettino di Archeologia 5–6 (1990), pp.180–185

Present location: Palazzo Spada, Rome (image)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 127 (image)

Numbered 37

Marble group, known as ‘Papirius’ or ‘Gruppo di Oreste ed Elettra’, 1st century ad, 192 cm (male figure). Ex-Villa Ludovisi (c. 1623–1901). Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.288–291 no. 71. Museo Nazionale Romano. Le Sculture [I/5], I marmi Ludovisi, compiled by Beatrice Palma and Lucilla de Lachenal (Rome 1983), pp.84–89 no. 35. Scultura antica in Palazzo Altemps, edited by Matilde De Angelis d’Ossat (Milan 2002), p.168. Winckelmann (1756), pp.345–346 (113, 6–114, 4)

Present location: Rome, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps, Inv. no. 8604 (image)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pls. 62–63 (plate legend Il fanciullo Papirio…; image, image)

Numbered 38

Marble of a seated female figure, usually identified as Agrippina the younger (Agrippina Minor), 1st century ad, 125 × 128 cm. Ex-Orti Farnesiani, Rome. Cf. Haskell & Penny (1981), p.133 (compared with the Agrippina in the Capitoline Museum). L’idea del Bello: Viaggio per Roma nel Seicento con Giovan Pietro Bellori, edited by Carlo Gasparri and Evelina Borea (Rome 2000), ii, p.256 no. 36 (entry by Federico Rausa). Winckelmann (1756), pp.362–363 (125, 38–40). Gasparri (2007), p.171 no. 133 (‘Catalogo dei disegni e delle stampe delle sculture della collezione farnese’)

Present location: Naples, Museo Nazionale, Inv. no. 6029 (image).Catalogo del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (1989), pp.156–157 no. 23; Flavia Coraggio, in Le sculture Farnese, 2. I ritratti, edited by Carlo Gasparri (Naples 2009), pp.78–80 no. 53.

Numbered 39

Marble sculpture of the Scythian Slave, a Roman copy of a Hellenistic original of the 3rd century bc, 105 cm. Ex-Villa Medici, Rome (acquired by the Medici family in 1578); sent to Florence in 1677. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.154–157 no. 11. Bober & Rubinstein (1986), pp.75–76 no. 33

Present location: Florence, Uffizi, Tribuna, Inv. no. 230 (image). Mansuelli, Galleria degli (1958–1961), i, pp.84–87 no. 55 (figs.57a-b)

Mosman most probably has drawn a plaster cast of the original marble.

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 41 (image); Gori (1734), iii, pl. 96 (image)

Numbered 40

Roman copy of a Hellenistic figure, 100–150 ad, 210 cm. Found c. 1546 on the Esquiline Hill (vigna Fusconi-Pighini); purchased by Clement xiv in 1770. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.263–265 no. 60. Winckelmann (1756), pp.395 (151, 23–30)

Present location: Rome, Musei Vaticani, Museo Pio-Clementino, Sala degli Animali, Inv. no. 490 (image). Amelung (1903–1908), ii, p.33–38 no. 10 (pls. 3, 12); Giandomenico Spinola, Il Museo Pio Clementino (Rome 1996), i, p.137 no. 40

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 141 (image)

Numbered 41

Marble statue of a philosopher, traditionally identified as Zeno the Stoic, Hellenistic sculpture from the 2nd century bc, 172 cm. Ex-Albani collections, Rome (reputedly found in excavations carried out by Cardinal Albani in 1701 at Civita Lavinia, a property of the Cesarini); ex-Villa Albani, Rome; purchased in 1733 by Clement xii for the Capitoline Museum (Albani Inventory, C21)

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 737 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.347–348 no. 8 (pl. 86)

Reproduced by Bottari (1750), pl. 90 (image); Magnan (1776), pl. 18 (image)

Numbered 42

Marble statue of a satyr, restored holding cymbals (kroupezion), known as the ‘Dancing’ or ‘Medici Faun’, 150–200 ad, 143 cm. Possibly found in Rome; ex-Medici collections, Rome; removed to Florence, and installed in the Tribuna of the Uffizi, by 1688. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.205–208 no. 34

Present location: Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, Inv. no. 220 (image). Mansuelli (Rome 1958–1961), i, p.80 no. 51

The legend beneath Mosman’s drawing does not locate this statue, which is known in many copies in various materials and sizes (Julia Habetzeder, ‘The impact of restoration: the example of the dancing satyr in the Uffizi’ in Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish institutes at Athens and Rome 5, 2012, pp.133–163, Appendix 1). The ‘original’ was removed from Rome to Florence by 1688. The drawing by Nicolas Dorigny for the anthology of Maffei (1704) omits the tree-support, which is shown here; G.D. Campiglia’s drawing published by Gori (1734) is similar, but clearly was not Mosman’s model either.

Compare the plaster replica in the Palazzo Corsini, where the left hand of the figure touches the support with the cymbal (Inv. 1204; Gioia de Luca, I monumenti antichi di Palazzo Corsini in Roma, Rome 1976, i, pp.39–42 no. 15 and pls. 27–31).

Reproduced by Jan de Bisschop, Paradigmata graphices variorum artificum (Amsterdam 1671), pls. 1–3 (image, image, image); Maffei (1704), pl. 35 (image); Gori (1734), iii, pl. 58 (image)

Numbered 43

Marble statue of the Roman martyr Santa Susanna by François Duquesnoy (1597–1643), 230 cm. Commissioned by the confraternity of the Roman bakers and installed in 1633 in the choir of Santa Maria di Loreto (situated across the street from Trajan’s Column). L’idea del Bello: Viaggio per Roma nel Seicento con Giovan Pietro Bellori, edited by Carlo Gasparri and Evelina Borea (Rome 2000), ii, pp.396, 398, 401–402 no. 5. Estelle Lingo, ‘The Greek Manner and a Christian “Canon”: François Duquesnoy’s “Saint Susanna”’ in The Art Bulletin 84 (2002), pp.65–93

Present location: Rome, Church of Santa Maria di Loreto (image)

Reproduced by Maffei (1704), pl. 161 (image)

Numbered 44

Roman statue of a faun, marble (rosso antico), 168 cm. Found by Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti in 1736 at Hadrian’s Villa; restored by Bartolomeo Cavaceppi and Clemente Bianchi, 1744–1746; given to the Capitoline Museum in 1746 by Benedict xiv. Haskell & Penny (1981), pp.213–215 no. 39. Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, scultore romano (1717– 1799), catalogue of an exhibition held at Museo del Palazzo di Venezia, Rome, 25 January–15 March 1994, edited by Maria Giulia Barberini and Carlo Gasparri (Rome 1994), p.23

Present location: Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 657 (image). Stuart Jones (1912), pp.309–310 no. 1 (pl. 77)

Reproduced by Bottari (1755), pl. 34 (image). Compare Magnan (1776), pl. 31 (image)

Abbreviated references are expanded in bibliography

1. The consummate collector: William Beckford’s letters to his bookseller, edited by Robert J. Gemmett (Norwich 2000), p.226.

2. Presented by the Earl of Exeter to the British Museum (2 January 1789), originally Add. Mss. 5343–5345, subsequently transferred to the Department of Prints & Drawings. The drawings are arranged in seven volumes; title-leaf (T.3,1a): ‘COLLECTION | OF | DRAWINGS, | By JOSEPH [sic] MOSMAN, | Of ROUS, in LORRAIN | Who died the 14th of August 1787, aged Fifty-eight Years Two Months and Eleven Days.’ The number of drawings in the series is variously stated; a total of 291 is given by Antony Griffiths and Reginald Williams, The Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum: user's guide (London 1987), p.139.

3. Roettgen (1993), pp.14, 140. Cf. Thomas Ashby, ‘Thomas Jenkins in Rome’ in Papers of the British School at Rome 6 (1913), pp.487–511 (p.488: the drawings ‘were intended to be engraved from; but I do not know whether this was ever done’); Jacob Hess, ‘Amaduzzi und Jenkins in Villa Giulia’ reprinted in Kunstgeschichtliche Studien zu Renaissance und Barock (Rome 1967), pp.309–326 (p.323).

4. See, generally, Louisa M. Connor Bulman, ‘The market for commissioned drawings after the antique’ in Georgian Group Journal 12 (2002), pp.59–73. On the role of drawings in the business of selling ancient sculptures, see Viccy Coltman, Classical sculpture and the culture of collecting in Britain since 1760 (Oxford 2009), pp.49–83: Chapter 2, ‘“The spoils of Roman grandeur”: correspondence collecting and the market in Rome’ (p.89, ‘paper tools’).

5. Roettgen (1993), pp.98, 140; Steffi Roettgen, Anton Raphael Mengs 1728–1779, Band 1: Das malerische und zeichnerische Werk (Munich 1999), nos. 37 WK4, 40 WK1, 47 WK 1, 88 WK1, 92 WK1, 95 WK3, 110 WK3, 113 WK4, 115 WK1, 116 WK2, 121 WK1, 123 WK 1, 307 WK6; cf. 114 GR3, 125 Wk1.

6. The portrait by Maron of Mosman is lost; it is documented by a drawing in the Exeter albums in the British Museum (T,3.1), signed Antonius Maron. pinxite and inscribed ‘The portrait of Nicolas Mosman | himself who drew the above as well | as the Collection of drawings for the | Rt Honble the Earl of Exeter. | The Picture is in the possession of | Thomas Jenkins’. Anton von Maron also drew or painted other members of this social and professional circle, including Mengs (British Museum, T,5.1), Jenkins, Byres, Winckelmann (Weimar, Schlossmuseum), and Cavaceppi (Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, KdZ 9402). See Paolo Coen, ‘Anton Von Maron, “Ritratto di James Byres”’ and ‘Anton Von Maron, “Ritratto di Thomas Jenkins”’ in Aequa Potestas. Le arti in gara a Roma nel Settecento, edited by Angela Cipriani (Rome 2000), pp.33–34 (no. i.21), p.41 (no. i.31).

7. Valeriani (1998), pp.152–154, ‘Appendice Documentaria’ (letters from Jenkins to Lord Exeter dated 11 March 1775, 23 September 1786, and 22 January 1792).

8. Jenkins brought Winckelmann an offer of financial help from Thomas Brand-Hollis (1719–1804); see the letter from Winckelmann to H.W. Muzel-Stosch, 7 December 1763 (J.J. Winckelmann, Briefe: Kritisch ‒ Historische Gesamtausgabe, edited by Walther Rehm, Berlin 1952–1957, ii, pp.360–361 no. 612).

9. The so-called ‘Kitharödenrelief’ (66 × 100 cm), depicting three deities, Leto, Artemis and Apollo, approaching an altar at which stands a winged figure of Victory (Villa Albani, Inv. 1014); H.-U. Cain, in Forschungen zur Villa Albani: Katalog der antiken Bildwerke. 1. Bildwerke im Treppenaufgang und im piano nobile des Casino (Berlin 1989), pp.380–388 no. 124.

10. The vignette is signed Nicolas Mosman del. et sculpt. and accompanies the ‘Vorrede’ (p.ix). For the other illustations, see Ernst Osterkamp, ‘Zierde und Beweis: Über die Illustrationsprinzipien von J.J. Winckelmanns Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums’ in Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift 89 (1989), pp.301–325 (pp.306–307, Mosman’s vignette reproduced).

11. The print is signed N. Mosman delin. | N. Mogalli sculp. and appears as plate 180. Winckelman holds an impression of this print in the portrait painted in 1768 by Anton von Maron (Stadtschloss, Weimar). The relief is still in the Villa Albani, displayed above a chimney-piece in a room designed around it c. 1757–1762 by the sculptor-architect Carlo Marchionni (Haskell & Penny, 1981, pp.65 fig. 34, 144–146 no. 6). J.J. Winckelmann, Schriften und Nachlaß, Bd. 6,1: Monumenti antichi inediti spiegati ed illustrati, edited by Adolf H. Borbein and Max Kunze (Mainz 2011), pp.xi–xii.

12. J.J. Winckelmann, Briefe, edited by Walther Rehm (Berlin 1952–1957), iii, p.531–532 (also pp.268, 520); ii, p.452; i, p.483 (series of 26 drawings in the Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin, possibly intended for the Monumenti inediti).

13. By 1762, Mengs had narrowed the canon of the best surviving antique sculptures to just five works, all of which are drawn by Mosman (sheets 13, 24, 29, 31, 33); see A.D. Potts, ‘Greek Sculpture and Roman Copies i: Anton Raphael Mengs and the Eighteenth Century’ in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980), pp.150–173 (p.159). Compare Winckelmann’s unpublished guidebook to the sculpture on display in private collections in Rome, written 1756 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms Fonds Allemands, 68): Joselita Raspi Serra, Il primo incontro di Winckelmann con le collezioni romane: Ville e palazzi di Roma, 1756 (Rome 2002–2005); J.J. Winckelmann, Schriften und Nachlass: Bd. 5,1: Ville e palazzi di Roma: Antiken in den römischen Sammlungen: Text und Kommentar, by Sascha Kansteiner, Brigitte Kuhn-Forte and Max Kunze (Mainz 2003).

14. Vatican: sheets 22, 28, 29, 31, 33.

15. Recent additions to the Capitoline collection: sheets 1, 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18, 23, 25, 41, 44. Cf. sheet 35 (transferred to the Capitoline Museum from the Vatican).

16. Barberini collection: sheet 32.

17. Villa Borghese: sheets 12, 24, 27.

18. Villa Casali: sheet 21.

19. Farnese collection: sheets 5, 7, 13, 30, 38.

20. Villa Giustiniani: sheets 2, 3.

21. Ludovisi: sheets 19, 37.

22. Villa Medici: sheet 14.

23. Pighini: sheet 40.

24. Palazzo Spada: sheet 36.

25. Palazzo Verospi: sheet 4.

26. Gordian A. Weber, Die Antikensammlung der Wilhelmine von Bayreuth (Munich 1996), pp.75, 84 (‘Ein Mercurio in Lebensgroise’) and fig. 14. Fendt (2012), i, pp.26–29; ii, pp.128–132 no. 28.

27. María del Carmen Alonso Rodríguez, ‘La colección de antigüedades comprada por Camillo Paderni en Roma para el rey Carlos iii’ in Illuminismo e ilustración: le antichità e i loro protagonisti in Spagna e in Italia nel xviii secolo, edited by José Beltrán Fortes, et al. (Rome 2003), pp.29–46.

28. Circumstances of the transaction are recounted by Fendt (2012), i, pp.29–32.

29. Some paintings reproduced by Mosman in the Exeter albums in the British Museum likewise were not in Rome, for example, Raphael’s ‘Madonna della Sedia’, which Mosman has inscribed ‘Raphael Sanctius Urbinas pinxit’ | In the Grand Dukes Collection at Florence’ (British Museum, T,5.22); and a painting by Guido Reni inscribed ‘The Original in the Sagresty of the Church of the Domenicans at Naples’ (T,3.14).

30. Posthumous inventory of ‘Gessi esistenti in t[ut]te le stanze, e luoghi della casa sud.a villa Barberini’ (Rome, Archivio di Stato, Trenta Notai Capitolini, uff. 4, Vincenzo Francesco Capponi, 1779, vol. 490, f.478r–481r) transcribed by Steffi Roettgen, ‘Zum Antikenbesitz des Anton Raphael Mengs und zur Geschichte und Wirkung seiner Formensammlung’ in Antikensammlungen des 18. Jahrhunderts, edited by Herbert Beck (Berlin 1981), pp.129–148 (pp.141–142 note 59): Mosman drawing 6: ‘Venere di Firenze’; Mengs’ cast ‘Venere di Medici di Firenze’. Drawing 26: ‘Lotta di Firenze’; cast ‘Il Gruppo de Lotatori di Firenze’. Drawing 39: ‘Rotino di Firenze’; cast ‘Schiavo di Villa Medici’. Drawing 42: ‘Faone’; cast ‘Fauno di Firenze che suona l'Crotali’. Cf. Moritz Kiderlen, Die Sammlung der Gipsabgüsse von Anton Raphael Mengs in Dresden. Katalog der Abgüsse, Rekonstruktionen, Nachbildungen und Modelle aus dem römischen Nachlaß des Malers in der Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Munich 2006), p.136 (‘vii. Castor e Pollux, de Madrit’).

31. Raccolta Di Statue Antiche E Moderne Data In Luce Sotto I Gloriosi Auspici Della Santita Di N.S. Papa Clemente XI. Da Domenico de Rossi. Illustrata Colle sposizioni a ciascheduna immagine Di Pavolo Alessandro Maffei Patrizio Volterrano E Cav. Dell’Ordine Di S. Stefano E Della Guardia Pontificia (Rome 1704; re-issued 1740).

32. Giovanni Gaetano Bottari, Musei Capitolini Tomus Primus [-Tertius] (Rome 1750–1755).

33. Statements that he was born in 1727 are erroneous. Nicolas was one of seven children of Joseph Mosman and Marie Mathias; see the baptismal registers of Haroué (C800560 Naissances 1660–1762), transcribed on Le site d'Eliane et Dominique.

34. Michel (1996), p.392 (14 August 1765), p.427 (25 January 1775).

35. Steffi Röttgen, ‘Antonius de Maron faciebat Romae. Zum Werk von Anton von Maron in Rom’ in Österreichische Künstler und Rom, Vom Barock zur Secession, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Vienna, May–June 1972 (Vienna [1972]), pp.35–52 (pdf).

36. Antonella Pampalone, ‘L’ambiente culturale romano intorno al 1760 e i riflessi sulla prima attività di Cristoforo Unterperger’ in Cristoforo Unterperger: un pittore fiemmese nell’Europa del Settecento, edited by Chiara Felicetti (Rome 1998), pp.16–26, considers the position of Unterberger, Mosman, and Friedrich Anders in the studio of Mengs before the latter’s departure for Madrid in 1761.

37. See Angela Cipriani and Enrico Valeriani, I Disegni di figura nell’Archivio storico dell’Accademia di San Luca, 3: Concorsi e Accademie del secolo xviii (1756–1795) (Rome 1991), pp.10 (A–392, 1758), 26 (A–417, 1762), 48 (A–445, 1766), 76 (A–469, 1771), 99 (A–499, 1775). Roettgen (1993), p.140, wrongly states: ‘The collection of drawings in the Accademia di San Luca in Rome contains a study by Mosman among the academic life drawings of 1757’. This is a misreading of Friedrich Noack, Das Deutschtum in Rom seit dem Ausgang des Mittelalters (Stuttgart 1927), i, p.324 (the drawing submitted was by Mengs); cf. Bibliotheca Hertziana, ‘Ausführliche Zeittafel zum Deutschtum in Rom’ q.v. January 1757 (pdf).

38. Michel (1996), pp.452–454. Friedrich Noack, ‘Schede Noack: Schedarium of the artists in Rome’ q.v. Mosmann (pdf).

39. Archivio del Vicariato di Roma, S. Andrea delle Frate, libr. matr. 1749–1771, folio 107 verso; cited by Michel (1996), p.392 (note 11). Cf. Winckelmann, Briefe, op. cit., iii, p.532 (unpublished Letter by Johann Friedrich Reiffenstein to Christian von Mechel).

40. Michel (1996), pp.391–392, 427.

41. John Thomas Smith, Nollekens and his times (London 1829), p.208. Mosman is identified by Friedrich Noack as one of the ‘soldati Avignonesi’ (‘Schede Noack: Schedarium of the artists in Rome’ q.v. Mosmann; pdf).

42. John Ingamells, A dictionary of British and Irish travellers in Italy, 1701–1800 (New Haven, CT 1997), pp.343–344.

43. Unpublished manuscript diary of Martin’s Grand Tour, 1763–1765, quoted by Ingamells, op. cit., p.344 (pp.644–646, entry for Martin). The drawing is British Museum, T,3.29 (The Penitent Magdalene, signed and inscribed: ‘Guidus. Pinxit | in the Barberini Pallace in Rome’).

44. Valeriani (1998), p.152, Letter from James Byres to Lord Exeter, 15 January 1772: ‘[Mosman] tells me that he works now, all the holy days for your lordship except Sundays’.

45. Hugh Brigstocke, ‘The 5th Earl of Exeter as Grand Tourist and Collector’ in Papers of the British School at Rome 72 (2004), pp.331–356 (series of voyages in 1679–1681, 1683–1684, 1699–1700).

46. Ingamells, op. cit., p.344.

47. The best account is given by John Horn, A history or description, general and circumstantial, of Burghley House (Shrewsbury 1797), pp.129–134 (‘Antiquities and curiosities of Burghley House’). Eric Till, ‘The ninth Earl of Exeter as an antiquarian’ in Northamptonshire past and present 55 (2002) pp.18–26, publishes the Burghley estate Masons Daybook of wages, 1771–1782, and is chiefly concerned with building work undertaken there and at Stamford Manor.

48. British Museum, 1760,0919.1 (image).

49. Oliver R. Impey, The Cecil family collects four centuries of decorative arts from Burghley House (London 1998), p.136 no. 47.

50. Impey, op. cit., p.150 no. 58.

51. Seymour Howard, ‘Boy on a Dolphin: Nollekens and Cavaceppi’ in The Art Bulletin 46 (1964), pp.177–189. The original for this work, supposedly designed by Raphael, belonged to Cavaceppi, and is illustrated in Cavaceppi’s Raccolta d'antiche statue, busti, teste cognite ed altre sculture antiche (Rome 1768), pl. 44. Lord Exeter’s version sits on a base copied from one of the Barberini candelabra restored by Cavaceppi.

52. The drawing is inserted among Mosman drawings in the Exeter albums, British Museum, T,5.53. The sheet is inscribed (recto) ‘From a Statue of Laocoön in the Capitol at Rome by Zannettio Casannova Director of the | Academy of Drawing at Dresden, 1764’ and (verso) ‘Zannetti Casanuova. Rome. 1764’. Cf. Roland Kanz, Giovanni Battista Casanova (1730–1795): eine Künstlerkarriere in Rom und Dresden (Munich 2008), p.34 Abb. 7 (Casanova’s drawing of the Capitoline Antinous, in Rome, Accademia di San Luca).

53. British Museum, 1764,0928.1. Simon Swynfen Jervis and Dudley Dodd, Roman splendour, English arcadia: the English taste for Pietre Dure and the Sixtus cabinet at Stourhead (London 2015), p.24 and fig. 29.

54. British Museum, 1771,0801.1; R.P. Hinks, Catalogue of the Greek, Etruscan & Roman Paintings & Mosaics in the British Museum: Paintings (London 1933), no. 63.

55. They are described by Horn, op. cit., p.132, as a ‘figure of Apollo, which is a copy by Giuseppe Claus, from the beautiful statue, at the Grand Duke's palace, on the Trinita di Mount, at Rome’ and ‘that of the Venus Bel Fresse, which is also a copy by the same hand, in exactly the same style’, each ‘about three feet high’; the first is probably the Tribuna Apollino now at Brocklesby Park, Lincolnshire, which is signed and dated Josephus Claus fecit 1766. Cf. Nicolas Penny, Catalogue of European Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford, 1992), i, pp.27–28 nos. 22–25.

56. Adolf Michaelis, Ancient marbles in Great Britain, translated by C.A.M. Fennell (Cambridge 1882), p.227 no. 5. The object is still at Brocklesby Park (image).

57. Horn, op. cit., pp.17–18: ‘a figure of Bacchus, which the late Earl, at a great expense, purchased at Rome… though well proportioned, [it] scarce exceeds five feet above the pedestal; which is itself three feet two inches in height. His right arm, in the hand of which he holds the cup, appears to have been joined to his body at the shoulder, from which it was formerly lopped off. Similar accidents seem to have happened to his left thigh, left wrist, and right knee’; Michaelis, op. cit., p.93 note 243.

58. Howard, op. cit., p.179 note 14.

59. Valeriani (1998), p.145 figs. 1–2; Impey, op. cit., pp.57, 134 no. 46a–46b; Art in Rome in the eighteenth century, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 16 March–28 May 2000, edited by Edgar Peters Bowron and Joseph J. Rishel (Philadelphia 2000), p.205 nos. 95–96 (Burghley House).

60. The chimney-piece appears as plate 1 in Piranesi’s Diverse maniere d'adornare i cammini of 1769, with legend: ‘Cammino che si vede nel Palazzo di Sua Eccza Milord Conte D; Exeter a Burghley in Inghilterra…’.

61. Valeriani (1998), p.150 figs. 10–11; Impey, op. cit., pp.130–133 nos. 45a–45b; Jervis and Dodd, op. cit., p.35 and fig. 40.

62. British Museum, T,3.7: Statue of the Farnese Hercules, whole-length, nude, resting on a lionskin and club, below which is an inscription in Greek (503 × 352 mm), signed and inscribed ‘In the Palazzo Farnese in Rome’. = ‘Farnese Hercules’ (Naples, Museo Nazionale, Inv. no. 6001; image). Compare our album, drawing 13 (‘Herculeo’, 494 × 350 mm). ● British Museum, T,3.6: Statue of Flora, whole-length, holding her skirts in her right hand, a wreath of flowers in her left (503 × 346 mm), signed and inscribed ‘Statue of Flora in Palazzo Farnese at Rome’. = ‘Flora Farnese’ (Naples, Museo Nazionale, Inv. no. 6409; image). ● British Museum, T,3.8: Statue of the fighting Gladiator, whole-length, nude, weight supported on his right leg, and left arm raised (497 × 344 mm), signed and inscribed ‘In the Villa Borghese near Rome’. = ‘Borghese Gladiator’ (Paris, Musée du Louvre, MA 527; image). Compare our album, drawing 24 (‘Gladiatore di Villa Borghese’, 505 × 345 mm). ● British Museum, T,5.48: Bust of Antinous, to right, with an elaborate hairstyle (432 × 314 mm), signed and inscribed ‘Bust of Antinous | in the Villa Dracone at [Frescati?]’. = ‘Antinous Mondragone’, discovered between 1713 and 1729 near the Borghese Villa Mondragone, above Frascati (Paris, Musée du Louvre, Ma 1205; image).

63. British Museum, T,3.9: Statue of an Empress in the character of Ceres, wearing classical dress, a torch in one hand and ears of corn in the other (455 × 311 mm), signed and inscribed ‘A statue of an Empress in the character of Ceres in the Capitol’. = ‘Hera Restored as Ceres with the Head of Faustina the Younger’, from the Albani collection (Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 633; Stuart Jones, 1912, p.290 no. 24 and pl. 70). ● British Museum, T,3.5: Statue of Zeus, whole-length, holding a scroll in his right hand (478 × 330 mm), signed and inscribed ‘The Statue of Zeus in the Capitol’. = ‘Statue of Zeus’, from the Vatican collection (Rome, Musei Capitolini; Stuart Jones, 1912, pp.40–41 no. 41 and pl. 6. ● British Museum, T,5.18: Bust of Messalina, in profile to left, wearing her fringe in tight ringlets and curls (197 × 164 mm), inscribed ‘From an ancient bust of Messalina in the Capitol’. = ‘Bust of a lady of Julio-Claudian period’, acquired in 1733 with the Albani collection, where identified as Messalina (Rome, Musei Capitolini; Stuart Jones, 1912, pp.190–191 no. 13 and pl. 48). ● British Museum, T,3.2: Statue of Flora, whole-length, holding some flowers in her left hand, the other hand upturned (458 × 297 mm), signed and inscribed ‘The Statue of Flora in the Capitol at Rome | found in the Villa Adrian at Tivoli’. = ‘Flora’, found in 1744 (Rome, Musei Capitolini, Inv. no. 733; image). Compare our album, drawing 18 (‘Flora di Campidoglio’, 510 × 350 mm). ● British Museum, T,3.3: Statue of a Muse, whole-length, wearing classical dress, holding a pipe in each hand and leaning against a pillar (420 × 257 mm), no inscription. = Possibly the version of ‘Satyr with flute’ in the Capitoline Museum, found on the Aventine in 1749 (Stuart Jones, 1912, p.93 no. 12 and pl. 18). ● British Museum, T,3.4: Statue of an Amazon, whole-length, wearing classical drapery, holding a bow with both hands, a quiver by her left side, by her feet a shield and axe (445 × 300 mm), no inscription. = ‘Statue of an Amazon preparing to leap’, from the D’Este collection, purchased 1753 (Rome, Musei Capitolini, 733; Stuart Jones, 1912, pp.342–344 no. 4; image). ● British Museum, T,5.47: Vase of Mithridates, fluted vase with an acanthus scroll handle at each side (456 × 329 mm), inscribed ‘The Vase of Mithridates found in the harbour of [Antrain?] now in the Capitol at Rome’. = ‘Krater of Mithridates V Eupator’, from Porto d’Anzio (Antium), donated by Benedict xiv (Rome, Musei Capitolini, MC 1068; image).