The manuscript diaries of three French travellers in Italy

Manuscript diary of his travels in Italy, 1739-1740, in the company of Charles de Brosses; bound circa 1754 with manuscripts by other authors, relating their own travels to Italy (in 1623 and 1664)

The journal of a tour through Italy made in 1739-1740 by Abraham-Guy de Migieu, the elder son of Abraham-François de Migieu (1682-1735), marquis de Savigny-sous-Beaune, président à mortier of the Parlement of Dijon. Written with different pens and inks, with phrases scored out, and other corrections, the manuscript seems the actual document compiled by the young traveller during his itinerary. The writer follows the usual conventions of manuscript travel diaries, presenting geographical, historical, and architectural information on major locations and landmarks, interlaced with his own observations and opinions. Some of the latter concern one of his travelling companions, Charles de Brosses (1709-1777), and offer an enlightening perspective on De Brosses’ published account of their journey. The free expression of the author’s feelings strongly suggests that he wrote for his own reference, and did not intend that his memoir should circulate among family and friends.

Bound with [Anonymous], Mémoire des plus excellens tableaux et statues qui sont dans les églises de Rome.

Bound with [Anonymous], Remarques sur le voyage d’Italie – Voyage d’Italie fait en 1664.

Bound with [Anonymous], Traité des anciennes familles de Rome.

Bound with [Anonymous], Traité du gouvernement civil et ecclésiastique de Rome.

Bound with [Cudanson, Guillaume (c. 1575-1640)?], Mémoire de mon voiage d’Italye commencé le jour de feste de la nostre dame d’aoust de l’année 1623.

The manuscript was preserved after Abraham-Guy’s death in 1749 by his younger brother, the bibliophile Anthelme-Michel-Laurent de Migieu (1723-1788). In 1754, Anthelme caused it be bound with other manuscript accounts of journeys made in Italy, recording the date and the price of the binding on the lower endpaper: 1754 | 4 li[vres] 10 s[ols]. He placed Abraham-Guy’s manuscript (15 folios) at the front of the volume, supplying himself a handwritten “title-page”: Voyage d’Italie par Abraham Guy Demigieu conseiller au parlement de dijon en 1739. An earlier manuscript journal, documenting a voyage to Italy undertaken by ‘Cudanson’ in 1623, was placed at the end: Mémoire de mon voiage d’Italye commencé le jour de feste de la nostre dame d’aoust de l’année 1623 (39 folios). In between were bound seventy folios of blank paper. On these blank leaves Anthelme copied four accounts of Italy which he found in manuscripts in the libraries of two friends, Charles-Marie Févret de Fontette (1710-1772) and abbé Jérôme Richard (1720-1795).

- Subjects

- Art, Italian - Early works to 1800

- Italy - Description and travel - Early works to 1800

- Authors/Creators

- Cudanson, Guillaume (?), c. 1575-1640

- De Migieu, Abraham-Guy, 1718-1749

- Owners

- Ivry, Charles, marquis de Richard d', 1786-1841

- Jammes, Pierre, 1925-2009

- Migieu, Abraham-Guy de, 1718-1749

- Migieu, Anthelme-Michel-Laurent de, marquis de Savigny, 1723-1788

- Vaulchier, Vicomtes de (Château de Savigny-lès-Beaune), 20th century

- Other names

- Bouhier, Jean, 1605-1671

- Brosses, Charles de, 1709-1777

- Fevret de Fontette, Charles-Marie, 1710-1772

- Potier de Novion, Claude (?), c. 1638-1722

- Richard, Jérôme, Abbé, 1720-1788/1795

De Migieu, Abraham-Guy

Dijon 4 April 1718 – 8 February 1749

Manuscript diary of his travels in Italy, 1739–1740, in the company of Charles de Brosses; bound circa 1754 with manuscripts by other authors, relating their own travels to Italy (in 1623 and 1664)

provenance Anthelme-Michel-Laurent de Migieu, marquis de Savigny (1723–1788), inscribed by him on lower endpaper Demigieu 1754 and 4 li[vres] 10s[ols]1 — sold by heirs, c 18052 — Nicolas, marquis de Richard d’Ivry (1762–1850), ex-libris dated 18093 — Vicomtes de Vaulchier, proprietors of Château de Savigny-lès-Beaune, c. 1921–19724 — Pierre Jammes (1925–2009) — his sale by Sotheby’s, ‘Rome et l’Italie: Collection d’un érudit bibliophile’, Paris, 12–13 October 2010, lot 55

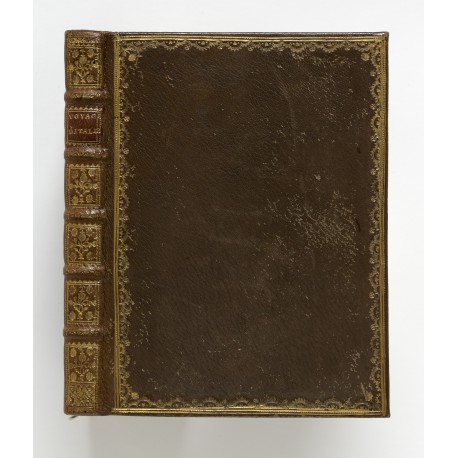

bound in 18th-century olive morocco, covers decorated by a gilt frame featuring a heart and flower tool; back divided into seven compartments, decorated in gilt by flower tools; lettering-piece Voyage d’Italie

The journal of a tour through italy made in 1739–1740 by Abraham-Guy de Migieu, the elder son of Abraham-François de Migieu (1682–1735), marquis de Savigny-sous-Beaune, président à mortier of the Parlement of Dijon. Written with different pens and inks, with phrases scored out, and other corrections, the manuscript seems the actual document compiled by the young traveller during his itinerary. The writer follows the usual conventions of manuscript travel diaries, presenting geographical, historical, and architectural information on major locations and landmarks, interlaced with his own observations and opinions. Some of the latter concern one of his travelling companions, Charles de Brosses (1709–1777), and offer an enlightening perspective on De Brosses’ own account of their journey.5 The free expression of the author’s feelings strongly suggests that he wrote for his own reference, and did not intend that his memoir should circulate among family and friends.

The manuscript was preserved after Abraham-Guy’s death in 1749 by his younger brother, the bibliophile Anthelme-Michel-Laurent de Migieu (1723–1788).6 In 1754, Anthelme caused it be bound with other manuscript accounts of journeys made in Italy, recording the date and the price of the binding on the lower endpaper: 1754 | 4 li[vres] 10 s[ols].He placed Abraham-Guy’s manuscript (15 folios) at the front of the volume, supplying himself a handwritten ‘title-page’: Voyage d’italie par abraham guy demigieu conseiller au parlement de dijon en 1739 (see Fig. 2). An earlier manuscript journal, documenting a voyage to Italy undertaken by ‘Cudanson’ in 1623, was placed at the end: Mémoire de mon voiage d’Italye commencé le jour de feste de la nostre dame d’aoust de l’année 1623 (39 folios). In between were bound seventy folios of blank paper.7 On these blank leaves Anthelme copied accounts of Italy which he found in manuscripts in the libraries of two friends, Charles-Marie Févret de Fontette (1710–1772) and abbé Jérôme Richard (1720–1795). Four accounts were transcribed by Anthelme in 1754; he evidently lost interest thereafter, and seventeen folios remain blank:

(1) Mémoire des plus excellens tableaux et statues qui sont dans les églises de Rome (8 folios), from the Févret de Fontette library;

(2) Remarques sur le voyage d’Italie – Voyage d’Italie fait en 1664 (27 folios), from abbé Richard’s library;

(3) Traité des anciennes familles de Rome (12 folios);

(4) Traité du gouvernement civil et ecclésiastique de Rome (6 folios), from the Févret de Fontette library.

This volume is no. 82 in a catalogue of Anthelme’s manuscript collection, listing some 210 items, which the collector prepared in 1760 for the Lyonese antiquary Pierre Adamoli.8

In recent years, historians of French continental tourism have worked to establish bibliographical control over their subject, compiling lists of the diaries, letters, and documents of voyagers, both manuscript and printed. Although still in progress, this research, led by François Brizay,9 Giovanni Dotoli,10 and Gilles Bertrand,11 suggests that surviving documents by French ‘precursors of the Grand Tour’ are scarce, and the two seventeenth-century accounts in our volume, by ‘Cudanson’ in 1623 and by an unnamed traveller in 1664, are propitious additions to a surprisingly slight corpus.12

Contents (in order of binding)

De Migieu, Abraham-Guy

1718 – 1749

Voyage d’Italie par Abraham Guy Demigieu conseiller au parlement de Dijon en 1739

quarto (220 × 165 mm), (15) ff., written on rectos and versos by Abraham-Guy de Migieu (except f.2v and f.15v, both blank), f.15r subscribed (by Anthelme de Migieu): Par Abraham Guy Demigieu Cons.er au P. de Dijon. Preceded by an otherwise blank leaf inscribed (by Anthelme de Migieu): Voyage d’Italie par Abraham Guy Demigieu conseiller au parlement de dijon en 1739.

paper manufactured by Antoine Palhion, at his mill Rochetaillée-en-Forez (Loire)13

literature René de Vaulchier, ‘Un Voyage en Italie au xviiie siècle’ in La Revue de Bourgogne 10 (1922), pp.5–15; Charles de Brosses, Lettres familières, edited by Giuseppina Cafasso; introduction, notes and bibliography by Letizia Norci Cagiano de Azevedo (Naples 1991), ii, p.661 (note 12)

Abraham-Guy departed from Dijon on 9 September 1739, chaperoned by Bénigne Legouz de Gerland (1695–1774). Passing through Lyon, Turin, Alexandria, Geneva, Pisa, Livorno, Florence, and Siena, they entered Rome on 16 December 1739. Here they met their compatriots Charles de Brosses (1709–1777) and Germain Anne Loppin de Montmort (1708–1767), like De Migieu conseillers laïques of the Parlement of Dijon;14 and the brothers Edmond La Curne (1697–1779) and Jean-Baptiste La Curne de Sainte-Pelaye (1697–1781). The six Burgundians resided in Rome until the end of February 1740, when De Brosses and the brothers La Curne returned to Dijon.

After De Brosses’s departure, Abraham-Guy left Rome for a two-week tour of Naples, Pozzuoli, and Vesuvius. He returned to Rome on 6 March 1740 expecting to witness the election of the new Pope. The unusual length of the conclave (18 February to 17 August 1740) made him impatient, and on 5 May 1740 he set off with Legouz and Loppin de Montmort for Bologna. They travelled from there to Venice, and afterwards to Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Mantua, and Modena. Abraham-Guy left his companions in Modena and returned home, journeying through Bologna, Reggio Emilia, Parma, Piacenza, Milan, and Turin, and arriving in Dijon on 1 September 1740.

In De Brosses’s epistolary account of his tour of Italy,15 there are several perceptive and witty descriptions of Abraham-Guy.16 These references are perhaps the chief reason Abraham-Guy de Migieu has a claim on our attention. Although his observations on his companions are less penetrating, Abraham-Guy records their activities in Rome meticulously, and his journal therefore is of interest to the many students of De Brosses’ voyage. Until now, their only access to it has been the excerpts published in 1922;17 the rediscovery of the manuscript will allow it to be explored fully for the first time.

Abraham-Guy’s journal provides a good idea of what it was like for a wealthy young man of elevated social status to travel in Italy during the mid-eighteenth century. He left Dijon liberally supplied with introductions: in Turin, he was presented by the French ambassador to Carlo Emanuele iii di Savoia; in Rome, he obtained an audience with Pope Clement xii, and was prominently seated at banquets, Christmas, and Holy week celebrations (1740); and in Naples, he was received by Carlo iii di Borbone, King of Naples, Sicily and Spain.

Abraham-Guy spent lavishly, far more than his companions (according to De Brosses), and his only constraint seems to have been a strong conscience. Throughout the journal, he reproaches himself for extravagant losses at cards; recording meanwhile even the most trivial of his expenses,18 and complaining of being exploited, if not actually cheated, on accommodation, transport, and food.

Abraham-Guy displays more than the usual traveller’s interest in art and architecture. Wherever he visits, but especially in Florence and Rome, he marvels at paintings and works of art, always naming the artists involved. He visits private collections as well as galleries, including ‘un petit cabinet’ of marble and bronze sculptures in Florence,19 and the epigraphic museum of the antiquary Scipione Maffei in Verona. No doubt at the insistence of Legouz, collections of natural history specimens also were inspected, including those assembled by Jean de Baillou in Florence, Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli in Bologna, and Lodovico Moscardo in Verona.

In De Brosses’s letters, Abraham-Guy emerges as a passionate collector of paintings and antiquities, possessing both knowledge and taste.20 Among purchases mentioned in Abraham-Guy’s journal are velvets and other textiles, bought in Genoa; precious stones (or jewels) and a snuff box, in Livorno; a copy of Baldinucci’s ‘Lives of the Painters’ and ‘reliques de sainte Madeleine’, in Florence; prints and ‘une pierre gravée’, in Rome. He seems to be a careful buyer: an opportunity in Florence to buy ‘des ouvriers des marqueteries’ from the grand-ducal workshops is dismissed with the explanation ‘elles sont bien cheres’ (f.7r). Near the end of his journey, in Milan, he writes ‘J’ay achete aussi beaucoup de tableaux – le prix n’est pas exorbitant’ (f.15r).

Since Abraham-Guy spent over eleven months – not including losses at the gambling table – some 35,000 livres,21 it very likely that many more works of art were acquired by him in Italy, and brought home to enrich the Château de Savigny.22 Abraham-Guy married on 8 January 1748 Marie Portail, widow of Joseph Joly de Bévy, président of the Chambre des Comptes of Dijon; he died without issue a year later, on 8 February 1749.23 His estate passed to his brother Anthelme, an avid collector not only of manuscripts, but also paintings and works of art of all kinds.24 Inventories of Anthelme’s collections are known and their analysis might lead to identification of the works of art acquired by Abraham-Guy during his voyage through Italy.25

[Anonymous]

Mémoire des plus excellens tableaux et statues qui sont dans les églises de Rome

(8) ff., written on rectos and versos in a single hand (except f.1r and f.8v, both blank), f.2v headed: Mémoire des plus excellens tableaux et statues qui sont dans les églises de Rome; f.7r subscribed: Le tout copié sur le MSS. de Mr. de Fontete qui s’est trouvé brulé en plusieurs endroits 1754

paper manufactured by Antoine Palhion (1698–1747), at his mill Rochetaillée-en-Forez (Loire)

A Mémoire listing the ‘best’ paintings and statues in forty Roman churches, the palazzi of the Pamphili, Farnese, Colonna, Peretti-Montalto, Giustiniani, and Borghese families, and the collections of Paolo Francesco Falconieri, Cardinal Antonio Barberini, and Maffeo Barberini, Principe di Palestrina (see Fig. 4). Although undated, internal evidence suggests that it was written after 1679.26

According to the subscription, this copy was made in 1754 from a fire-damaged manuscript in the Févret de Fontette library (losses in the original are indicated by interstices). The copyist, Anthelme de Migieu, was related by marriage to the Févret de Fontette family: his aunt, Barbe-Charlotte de Migieu (1684–1764), married in 1709 Jacques-Charles Févret de Fontette (1683–1728). Their son, Charles-Marie Févret de Fontette (1710–1772), member of the Académie de Dijon in 1753, author of the second edition of Jacques Lelong’s Bibliothèque historique de la France (five volumes, Paris 1768–1778), became custodian of the family library.

In 1772, the Févret de Fontette library was dispersed;27 shortly thereafter, a large number of manuscripts entered the Département des Manuscrits28 and Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal29 of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, however no version of this Mémoire can be identified in the catalogues of those collections. It is likely the original manuscript in the Févret de Fontette library – already much damaged in 1754 – has not survived.

[Anonymous]

Remarques sur le voyage d’Italie – Voyage d’Italie fait en 1664

(27) ff., written on rectos and versos in a single hand (except f.1r, blank), f.1v: Remarques sur le voyage d’Italie, f.4v: Voyage d’Italie fait en 1664; f.27v: Icy le MSS. s’est trouvé manquer | Seulement par quelques articles détachés il paroit que celuy qui a fait ce voyage a depensé pendant qui il a duré douze mille neuf cent vint quatre livres 12924| il se pourroit que l’autheur fut un Sgr. de Lantenay. | Le tout extrait du MSS. original appartenant à Monsieur l’abbé Richard chanoine de St Michel ainsy que les remarques sur le voyage d’Italie qui le précèdent. 1754

paper manufactured by Antoine Palhion (1698–1747), at his mill Rochetaillée-en-Forez (Loire)

An account of a year-long tour of Italy, commencing in Paris on 1 May 1664, and proceeding via Lyon (20 May–7 June), Turin (4–10 July), Genoa (14–16 July), Milan (19–22 July), Parma, Modena, Mantua, Verona, Vicenza, Venice (2–14 August), Ferrara, Bologna (23–28 August), Rimini, Ancona, Loreto, Recanati, and Assisi, to Rome, entered on 21 September 1664.

The unnamed traveller remained in Rome for five months, punctuated by a two-week tour of Naples, Pozzuoli, Vesuvius, Capua, and Frascati. He departed Rome on 21 April 1665, travelling via Montefiascone, Viterbo, Siena, Florence (25–28 April), Lucca, Pisa, Livorno, and Genoa, to Turin (4–16 May). Here he observed the wedding festivities on 10 May 1665 of Carlo Emanuele ii di Savoia and Maria Giovanna Battista di Savoia Nemours. He departed Savoy via Chambéry and arrived in Lyon on 23 May 1665 (here the account terminates).

It is a hybrid of aide-mémoire and guidebook: a meticulous accounting of expenditure on lodging and food (see Fig. 5) is blended with discourses – on the governance of the Republic of Venice, the shrines of Loreto, the treasures housed in the Vatican and in Grand-Ducal collections in Florence, among them – which read like extracts from written sources, or disquisitions by a tutor, or by a cicerone while conducting the traveller around these sights. The traveller seems to be a wealthy young man, albeit one determined to demonstrate to a parent or benefactor his prudence and economy. He is more often interested in matters of archaeological, antiquarian, and historic interest, than in works of art. He has a particular interest in recording epitaphs.30

In a lengthy subscription to the manuscript, dated 1754, the copyist (Anthelme de Migieu) conjectures that the unnamed traveller was a ‘Seigneur de Lantenay’. This supposition may depend on external evidence – the copyist had additional papers (‘quelques articles détachés’), and from these calculated that the cost of the entire voyage was 12,924 livres – or else the traveller’s identity was deduced from the text: the stairs and balustrades of a palazzo seen in Florence are compared ‘avec la balustrade pareille a cette de Lantenay’ (f.23r).

Situated about 20 km north-west of Dijon, the ancient Château de Lantenay was being renovated31 at this time by Jean Bouhier (1607–1671), a wealthy conseiller of the Parlement of Bourgogne, the founder of the ‘Bibliothèque Bouhier’. He had two sons, Bénigne (1635–1703)32 and Benoit-Bernard (1642–1682);33 the latter’s circumstances were more favourable to undertaking a tour of Italy in 1664.

The copyist indicates that the Voyage d’Italie fait en 1664 and prefatory Remarques were found in an imperfect manuscript belonging to Jérôme Richard (c. 1720–1795), prêtre mépartiste of the church of Saint-Michel at Dijon. Otherwise unknown as an owner of manuscripts, the abbé Richard may have acquired it in anticipation of his own voyage to Italy, made in 1761–1762 as companion to Marc-Antoine Bernard Claude Chartraire, marquis de Bourbonne (1737–1781).34 The marquis de Bourbonne had inherited the Bibliothèque Bouhier and in 1753 lent one of its manuscripts to Anthelme de Migieu for copying;35 did the marquis perhaps lend manuscripts to the abbé Richard? Was a Bouhier manuscript the original from which in 1754 the Remarques and Voyage d’Italie fait en 1664 were copied by Anthelme de Migieu?36 And was this why Anthelme de Migieu wrote at the end of his copy ‘il se pourroit que l’autheur fut un Sgr. de Lantenay’?

A further clue to authorship lies in the text, where the writer announces: ‘Le 1er May 1664 parti de Paris avec Mr le Chev[alier] du Novion et Mr de Molinet’ (f.4v). The ‘Chevalier de Novion’ is perhaps Claude (c. 1638–1722)37 or Jacques (1647–1709),38 younger sons of Nicolas Potier de Novion (1618/1619–1693), president à mortier of the Parlement of Paris.39 The ‘Mr de Molinet’ (du Molinet, or Moulinet?) is unidentifiable; he may have been a tutor.

[Anonymous]

Traité des anciennes familles de Rome

(12) ff., written on rectos and versos in a single hand (except f.1r, blank); on f.1v: Traité des anciennes familles de Rome

paper manufactured by Antoine Palhion (1698–1747), at his mill Rochetaillée-en-Forez (Loire)

An account of the most powerful families of Rome, discussed in the order of their perceived antiquity, commencing with the Orsini, Colonna, Conti, Savelli, Gaetani, Cesi, Cesarini, Sforza, Frangepani, Farnese, Altemps, Mattei, Caffarelli, Lanti, Muti, Aldobrandini, Salviati, and Strozzi, and then families of lesser seniority: a ‘Seconde Classe des familles qui ont plus de 300 ans de noblesse’, a ‘Troisième des classes des familles depuis 200 ans’, and ‘Familles enrichies depuis 50 ans’.

The Traité concludes with a list of popes, in reverse chronological order, from Innocent x (Giovanni Battista Pamphilj, 1644–1655) to Boniface viii (Benedetto Caetani, 1294–1303), with more detailed entries supplied for popes of Roman families.

[Anonymous]

Traité du gouvernement civil et ecclésiastique de Rome

(6) ff., written on rectos and versos in a single hand (except f.6v, blank), on f1r: Traité du gouvernement civil et ecclésiastique de Rome; f.6r: Copié sur le MSS appartenant à Monsieur Fevret de Fontete conseiller au parlement de bourgogne. Il parait avoir été composé vers l’an 1680, Ferdinand de Medicis étant grand duc de Toscane. 1754.

(17) ff., blank leaves

paper manufactured by Antoine Palhion (1698–1747), at his mill Rochetaillée-en-Forez (Loire)

A discourse on the ecclesiastical and temporal government of Rome, explaining the operation of the courts, the powers invested in the governor of Rome, the auditors of the Rota, magistrates, and other officials.

According to Anthelme de Migieu’s subscription, he copied it from a manuscript in the library of Charles-Marie Févret de Fontette, dated about 1680: ‘Copié sur le MSS appartenant à Monsieur Févret de Fontete conseiller au parlement de bourgogne. Il paroit avoir été composé vers l’an 1680, Ferdinand [iii] de Medicis étant grand duc de Toscane [1663–1713]’ (see Fig. 6). The lack of a subscription to the immediately preceding Traité des anciennes familles de Rome may signify that it was copied from the same manuscript.

Several ancestors of Charles-Marie Févret de Fontette (1710–1772) had journeyed in Italy and are possible authors of these works. The brothers Charles Févret, sieur de Saint Mesmin (1652–1733) and Jacques Févret (1655–1694), respectively Charles-Marie’s grandfather and great-uncle, travelled together in Italy in 1674–1675 (they were in Rome from 12 October–17 April 1675).40 Another great-uncle, Pierre Févret (1660–1692), made a journey in 1684;41 and a great-great-uncle Pierre Févret (1625–1706), travelled in Italy twice, in 1661 and in 1692.42

In 1772, the Févret de Fontette library was dispersed: the manuscripts were acquired by Esmonin de Dampierre, président of the Parlement of Dijon,43 who in 1779–1780 transferred a part to Antoine-René de Voyer, marquis de Paulmy, founder of the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal.44 In 1781, the marquis de Paulmy divided his share with the historian Jacob-Nicolas Moreau. In this way a large number of manuscripts from the Févret de Fontette collection entered the Département des Manuscrits and Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

A Traicte des anciennes familles de Rome is reported within the ‘portefeuilles de Févret de Fontette’ in the Département des Manuscrits (Fonds Moreau); it could be related to the Traité des anciennes familles de Rome in our volume, either as the original from which our manuscript was copied, or as yet another copy, and requires investigation.45

An alternative source is a volume formerly in the Jesuit Collège des Godrans in Dijon and now preserved in the Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon. Bearing the early exlibris of the library (Ex Bibliotheca publica collegii Divio-Godranii), it contains a collection of treatises on Rome written during the papacy of Innocent xi (Benedetto Odescalchi, 1676–1689), among which are (f.41) ‘Familles de la noblesse de Rome’ and (f.51) ‘Tableau du gouvernement de Rome’.46

The library of the Collège des Godrans had received in 1701 the substantial library collected by Pierre Févret (1625–1706);47 in later years it was supported by Charles-Marie Févret de Fontette.48 Either member of the family might have presented this manuscript to the Collège des Godrans; it also demands investigation.

[Cudanson, Guillaume?]

c. 1575 – 1640

Mémoire de mon voiage d’Italye commencé le jour de feste de la nostre dame d’aoust de l’année 1623

(39) ff., of which the last five are blanks (apart from a few notations on f.38v), written on rectos and versos in a single hand, on f.1r: Mémoire de mon voiage d’Italye commencé le jour de feste de la nostre dame d’aoust de l’année 1623, and f.34v subscribed: Cudanson.

paper no watermark observed

A retrospective record of a year-long journey made through Italy (15 August 1623–5 July 1624), copied out after the traveller’s return home ‘en bonne santé’ from rough papers and notes for presentation to a friend or relation. The intended recipient of the memoir is not identified; frequent comparisons of churches and other Italian monuments with Parisian landmarks imply that he (like the writer) was familiar with Paris, and detailed descriptions of holy relics and shrines, and reports of rites and ceremonies, suggest particular interest in such matters, possibly as a member of the clergy. The expenses of the journey are not mentioned. It is notable also that none of the problems of travel – difficulties with transport, accommodation, and food – is communicated by the writer, nor does he relate untoward experiences.

Commencing his journey in Paris, the writer travelled via Lyon and Chambéry to Turin, where he arrived on 29 August and rested four days, visiting churches and marvelling at the Santa Sindone. Milan, Piacenza, Parma, Modena, Bologna, Florence, and Siena are among places visited before the traveller entered Rome on 12 October 1623. Apart from a trip to Naples (25 February–12 March 1624), he remained in Rome for six months. He declares all of the city’s churches to be worth visiting.

A detailed account is provided of the ‘Possessio dei’ Papi’, the ceremony by which the new Pope Urban viii took possession of the Church of S. Giovanni in Laterano, as the Cathedral of his bishopric in Rome (19 November 1623).49 Other occasions described at length are a mass in St Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Eve; another mass (8 January) after which ‘Cudanson’ received a papal blessing, kissed the pope’s feet, and obtained an indulgence of three hundred days; the feast of the Annunciation of the Virgin (25 March), when he observed the papal cavalcade, and witnessed the custom of presenting a dowry to 400 virgines pauperes; and masses celebrated by the Pope on Maundy Thursday and on Easter 1624. A description of the Roman Rota (ecclesiastical court) and also the law court of Naples are given, with the latter compared to the Parisian court.

On 30 April 1624 the writer departed Rome, visiting Loreto, Ancona, Fano, Faenza, Ferrara, Rovigo, Padua, and Venice, where he arrived on 12 May. A full account is made of its Ascension Day celebrations. On 23 May he departed, travelling via Vicenza to Verona, where on Pentecost Sunday he witnessed a procession of 2000 citizens. He travelled thence to Brescia, and afterwards to Crema; there he was received in ‘ung petit palais a ung comte qui ce monstra très courtois envers la compagnye’ (f.31r, the only reference in the journal to companions on his voyage). Travelling via Milan and Genoa, he arrived in Lyon on 17 June, where he rested for ten days, before returning to Paris.

The bold subscription of the writer has been variously read, as ‘Andanson’ and ‘Adanson’,50 ‘Gudanson’ and ‘Oudanson’.51 Another reading is ‘Cudanson’, the surname of a large family residing about fifteen kilometres north of Paris in the villages of Aubervilliers, La Courneuve, and Stains (Seine-Saint-Denis, Île de France). At least one member of this family was of appropriate age and social status in 1623 to be our traveller: Guillaume Cudanson (c. 1575–24 April 1640), vigneron of Stains, sergent du bailli (1617) and marguillier de l’œuvre et fabrique of Stains (1618). Guillaume had married c. 1598 Barthelemie Delamare of Stains and had issue one child, a daughter, Jeanne (Gemme), born 1602 and married 1621. After the death of his wife (before 1618), Guillaume did not remarry.52

The manuscript may have been acquired in Paris in the 1750s, when Anthelme de Migieu was an active buyer in the book trade and salerooms.53

1. For the collector’s inscription, recording the date and the cost of the binding, see Paul Needham, ‘A note on de Migieu as Collector’ in Bulletin du Bibliophile (1989), no. 2, p.377.

2. Antoine François Delandine, Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque de Lyon (Paris 1812), ii, p.113 no. 844: ‘Son riche cabinet a été vendu et dispersé, en 1805, par ses héritiers’.

3. Léon Quantin, ‘Ex-libris bourguignons: liste sommaire’ in Bulletin de la Société archéologique, historique et artistique, Le vieux papier 4 (1906), p.49.

4. The manuscript is located in November 1921 in the ‘Archives du château de Savigny-lès-Beaune’ by René de Vaulchier, ‘Un Voyage en Italie au xviiie siècle’ in La Revue de Bourgogne 10 (1922), p.6 (note 1). The archive was dispersed c. 1972, after the death of the last proprietor of the Château de Savigny; in 1975–1976 a substantial part was acquired from a Parisian bookseller by the Archives départementales de la Côte d’Or, and is now Fonds 46F. See Guide des archives de la Côte-d’Or, compiled by Jean Rigault (Dijon 1984), pp.205–206.

5. De Brosses’s account of his Italian travels, a collection of letters addressed to his friends in Dijon, was first published in 1799; for its long bibliography, see the critical edition, Lettres familières, edited by Giuseppina Cafasso and Letizia Norci Cagiano de Azevedo (Naples 1991).

6. For biographical details of A.M.L. de Migeau, see Élysée de Sérésin, Notre Livre de famille: les Reynold de Sérésin et leurs alliés, notices généalogiques, concernant 32 familles de Dombes, Bresse, Dauphiné, Bourgogne, etc. (Dijon 1908), pp.71–72.

7. This paper – also the binder’s endleaves – was manufactured by Antoine Palhion (1698–1747), at his mill Rochetaillée-en-Forez (Loire). The mark is a Lion rampant du Lyonnais; en chef trois fleurs de lis et entoure de branches feuillues; and countermark, A [fleur-de-lys] Palhion accompanied by two crowns and a bunch of grapes. Similar watermarks are reproduced by Raymond Gaudriault, Filigranes et autres caractéristiques des papiers fabriqués en France aux xviie et xviiie siècles (Paris 1995), p.251 and pls. 88 fig. 776 (c. 1720), 136, (c. 1735); see Louis Veron de la Combe, Le centre papetier Velay-Forez: la papeterie de Saintignac les Crouzet (Grenoble 1950), pp.49–50, 74.

8. Lyon, Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon, Ms PA 80: A.M.L. de Migieu, Catalogue des manuscrits de la bibliothèque du château de Savigny, appartenant à M. de Migieu, ancien officier aux gardes françoises, chevalier de Saint Louis, 1760 (27 folios, 202 × 152 mm). The catalogue was published by Henri Omont, ‘Un Bibliophile bourguignon au xviiie siècle: Collection de manuscrits du Marquis de Migieu au château de Savigny-les-Beaune (1760)’ in Revue de Bibliothèque 11 (Paris 1901), pp.235–296; offprint (Paris 1902), p.29 no. 82. On its genesis, see Yann Sordet, L’amour des livres au siècle des Lumières: Pierre Adamoli et ses collections (Paris 2001), pp.116, 131–132, 297–299.

9. François Brizay has identified written records by 32 French travellers in Italy between 1595 and 1694; see F. Brizay, ‘Remarques sur les aspects matériels du voyage français en Italie au xviie siècle’ in Le Voyage français en Italie. Actes du colloque international de Capitolo-Monopoli, 11–12 mai 2007, edited by Giovanni Dotoli (Fasano & Paris 2007), pp.45–61. The same travellers are profiled in F. Brizay, Touristes du Grand Siècle: le voyage d’Italie au xviie siècle (Paris 2006).

10. A collaborative project covering the same period as Brizay, but with more inclusive criteria, increases the number of travellers to about eighty; see Vito Castiglione Minischetti, Giovanni Dotoli, and Roger Musnik, Le voyage français en Italie des origines au xviiie siècle: bibliographie analytique (Fasano & Paris 2006), pp.107–185.

11. Although focused on the later period, Gilles Bertrand lists printed and manuscript records of seventeenth-century French tourists in Italy: see Paul Guiton et l’Italie des voyageurs au xviiie siècle: son projet de bibliographie critique des voyageurs français en Italie: deux manuscrits (R 9707 et R 9705) de la Bibliothèque municipale de Grenoble, edited by Gilles Bertrand (Moncalieri [1999]), pp.105–111: ‘Fiches rassemblées dans la liasse des Précurseurs au xvii siècle’ (57 travellers, of whom six before 1623 and 24 before 1664); and G. Bertrand, Le grand tour revisité: pour une archéologie du tourisme: le voyage des français en Italie (milieu xviiie siècle–début xixe siècle) (Rome 2008), pp.557–563: ‘Manuscrits de voyages en Italie [1660–1750]’ (33 are listed); pp.585–587: ‘Récits de voyages accomplis et publiés avant 1700’ (25 are listed).

12. In comparison, manuscripts by 40 travellers between 1575 and 1698 are listed by Lorna Watson, The errant pen: manuscript journals of British travellers to Italy (La Spezia 2000), pp.3–10.

13. See above (note 7). The mill was active 1732–1746.

14. Abraham-Guy was received in office in July 1738, Bénigne Legouz de Gerland in January 1739, Charles de Brosses in February 1730, and Loppin de Montmort in November 1731; see A.-S. Des Marches, Histoire du Parlement de Bourgogne de 1733 à 1790 (Chalon-sur-Saône 1851), pp.7, 52, 54. De Brosses had commenced his journey on 30 May 1739, met his cousin Loppin de Montmort at Lyon, and entered Rome on 19 October 1739.

15. First published in 1799, and often reprinted (see note 5 above). Legouz de Gerland also kept a manuscript journal during the voyage, now lost; see P. Perrenet, ‘Figures oubliées: Legouz de Gerland’ in La Revue de Bourgogne 14 (1926), pp. 672–681; and Bertrand, Le grand tour revisité (op. cit.), pp.148, 562.

16. For example, Lettre xl, where De Brosses writes of Abraham-Guy: ‘Je n’étois en aucune liaison avec luy quand il est arrivé icy; elle se forme depuis de jour en jour entre nous deux. Je vous ay mandé que Legouz et lui ne s’accordoient pas trop bien; depuis que nous sommes tous réunis, comme nous avons trois carrosses, nous allons deux à deux, les deux frères ensemble, Legouz s’est mis avec Loppin, ainsi nous nous sommes trouvés Migieu et moy, ce qui nous a donné lieu, étant plus souvent ensemble, de faire une connaissance plus particulière. Il est froid et son abord ne prévient pas; il est testu mais, dans le vrai, sa contrariété n’est que dans le discours. Il est complaisant en actions; il a le cœur bon, franc, plein de droiture, noble et désintéressé autant qu’il soit possible. En tout, c’est un garçon fort estimable’ (De Brosses, Lettres familières, op. cit., ii, pp.726–727). Abraham-Guy also features in Lettres xxxviii, xlix, lvi, lvii.

17. Vaulchier (op. cit.), pp.5–15; for recent scholarship, see Letizia Norci Cagiano De Azevedo, Lo specchio del viaggiatore: scenari italiani tra Barocco e Romanticismo (Rome 1992), pp.14, 32, 207 (references to Abraham-Guy); and her ‘Borgognoni in Italia (1739–40)’ in Quaderni del Dipartimento di letterature Comparate 2 (2006), pp.175–183 (references to Abraham-Guy: pp.178, 181–182).

18. For example, when Abraham-Guy and Legouz arrived in Rome (16 December 1739), they found accommodation at the select hotel Monte d’Oro on the Piazza di Spagna, which they found ‘bonne mais chere’ (f.9r). ‘Des le lendemain nous avons mange avec messieurs de Lacurne, de Brosses et Gemeaux [Loppin] dans leur maison garnie où ils sont assez bien. Nous donnons cinq paules par jour trois pour le dîner et deux pour le souper, qui est peu de chose, nous donnons deux paules par jour pour les domestiques […] Je suis sorti du Monte d’Oro le dix huit et je suis venu coucher en place d’Espagne au caffe j’ay loue un appartement à huit écus par mois a commencer du dix huit’. Economising further, Abraham-Guy arranged to take his meals with the others for five paules per day.

19. He was guided by ‘Sieur Bianchi’, presumably Giuseppe Bianchi (son or nephew of Stefano, 1662–1738), later steward of the Medici galleries. Abraham-Guy gave Bianchi four sequins for his trouble, commenting: (f.7v) ‘les Anglais en donnent dix c’est toujours bien cher et je crois qu’il est inutile de se piquer de générosité par parce que plus on donne et plus on vous demande […] En Italie on trouve partout des gens qui ne se lassent pas de demander, mais il ne faut pas non plus se lasser de refuser […] Tout le monde est d’accord pour piller les étrangers’.

20. De Brossses, Lettre xl: ‘Il [De Migieu] achète aussi beaucoup en divers genres de curiositez, comme bronzes, estampes, desseins et pierres gravées […] Migieu aime assez les bonnes choses et s’y entend; il a du fond d’esprit, des connaissances et un grand attachement à l’étude’ (Lettres familières, op. cit., ii, p.726).

21. Vaulchier (op. cit.), p.15.

22. The richness of Abraham-Guy’s collections is often mentioned, without descriptive detail; see the commentary by Letizia Norci Cagiano de Azevedo in De Brosses, Lettres familières (op. cit.), ii, p.726 (note): ‘les tableaux et les antiquités dont il possédait une riche collection (achetée en grande partie en Italie)’. An anonymous commentator, reflecting on De Brosses’s account of Abraham-Guy’s purchases (bronzes, prints, drawings, and cameos) in Lettre xl, writes: ‘il est peu probable que le président de Brosses ait voulu donner une énumération limitative et en peut présumer que M. de Migieu dut récolter d’autres objets que ceux mentionnes par de Brosses’ (‘Beaune, Savigny, Sainte-Marguerite. Comte rendu de l’excursion faite par la Société Éduenne le 24 mai 1903’ in Mémoires de la Société Éduenne, new series, 31, 1903, p.331).

23. Des Marches (op. cit.), p.52.

24. Anthelme’s collections were intended to serve as illustrations for an encyclopaedia of the arts; only a portion of this was ever published, as Recueil des sceaux du Moyen-Âge dits sceaux gothiques (Paris 1779). In 1810 his heirs sold 1100 works of art, including enamels, ceramics, antique glass, weapons, and medieval objects, to the Musée de Lyon; see Jean-François Garmier, ‘Le goût du Moyen-Age chez les collectionneurs lyonnais du xixe siècle’ in Revue de l’Art 47 (1980), pp.54, 61 (note 23). Other works of art were still at the Chateau de Savigny in the 1920s, including a limestone column of a King made in the royal abbey of Saint Denis c. 1150 (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

25. A ‘Livre de Dépenses’ in the archive of the Château de Savigny was consulted by Leonard J. Slatkes, Dirck van Baburen (c. 1595–1624): a Dutch painter in Utrecht and Rome (Utrecht [1965]), pp.54, 112 no. A8, for the provenance of ‘an historical scene’ (Baburen’s last work executed in Italy, c. 1620). Another inventory is cited by Georgette Dargent, ‘La Madeleine dans l’œuvre de Simon Vouet’ in Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, Année 1959 (1960), pp.35, 38–39 (the painting is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art).

26. In the entry for the villa of Cardinal Alessandro Peretti-Montalto, the writer mentions the cycle of eleven paintings with stories from the life of Alexander the Great, and indicates that Domenichino’s ‘Timoclea before Alexander’ is a copy replacing an original ‘vendu et porté en france’ (f.5r). ‘Timoclea’ is mentioned by Bellori as being in the villa in 1672; it was removed in Passeri’s lifetime (d. 22 April 1679), sent to France, and by 1685 had entered the collection of Louis xiv (Erich Schleier, ‘Domenichino, Lanfranco, Albani, and Cardinal Montalto’s Alexander Cycle’ in The Art Bulletin, 50, 1968, pp.188, 192).

27. Some of the manuscripts in the library are listed by Févret de Fontette in his revision of Lelong, Bibliothèque historique de la France (Paris 1772), iii, pp.460–493 nos. 36073–37331; see also Bibliothèque nationale de France, Reserve Pet Fol-YE-28: Catalogue chronologique de la collection de Févret de Fontette, 1770; and Dijon, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms 1053: Inventaire alphabétique des manuscrits et des pièces non reliées de la bibliothèque de Charles-Marie Fevret de Fontette.

28. Bibliothèque nationale, Inventaire des manuscrits de la collection Moreau, compiled by Henri Omont (Paris 1891), pp.40–68 nos. 734–861. Included within the ‘portefeuilles de Févret de Fontette’ are travel manuscripts, among them (Portefeuille lvii, pièce 16) a ‘Journal d’un voyage en Italie, 1606’ (Voyage d’Italie 1606, edited by Michel Bideaux, Moncalieri & Geneva 1982).

29. See Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Catalogue des Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, compiled by Henry Martin (Paris 1892), v, pp.434–435 nos. 5765–5766 (inventories of portefeuilles i–xcii).

30. These include: (f.4r), a epigraph in the fabric of the mausoleum of the senatorial Plautii, near Ponte Lucano, Tivoli (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XIV 3605); (f.11v), an epigraph on the tomb of Ariosto erected in 1612 in the Chiesa di S. Benedetto, Ferrara; (f.12v), an epigraph commemorating the Council of Ariminum placed in 1637 on the façade of the Chiesa di S. Apollinare di Cattolica, Rimini; (f.13r), an epigraph on the arch of Trajan at Ancona (CIL IX 5894); (f.22r), an inscription in the Sala del Parnasso of the Teatro dell’Acqua at the Villa Aldobrandini; (f.24v), the inscription on Girolamo Lombardo’s base for the ‘Idolino di Pesaro’ in Florence; and (f.26v), the inscription on the monument to ‘Il gran’ Roldano’ (d. 1605, aged 9), a dog given to Andrea Doria by Charles v, erected in the gardens of the Palazzo Doria in Genoa.

31. Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, L’architecture à la française: du milieu du xve siècle à la fin du xviiie siècle (Paris 1982), p.171; and the same author, in L’éscalier dans l’architecture de la Renaissance (Paris 1985), p.87.

32. Bénigne was a student of law in Paris from 1653 until about 1655, assisting his father there in the acquisition of books and manuscripts; see Delisle (op. cit.), ii, pp.266–279. He became conseiller to the Parlement of Dijon in 1655 and president à mortier in 1665; he married Claire de la Toison in 1668.

33. Benoit-Bernard married Claude-Marie Gagne in 1670; see E. Debrie, ‘Un mariage dijonais en 1670’ in Bulletin d’histoire, de littérature & d’art religieux du Diocèse de Dijon 17 (1899), pp.181–220. In Sotheby’s sale catalogue, 12–13 October 2010 (op. cit.), p.42, his father, Jean Bouhier, is proposed as the traveller.

34.The abbé Richard’s account of their journey was published as Description historique et critique de l’Italie, ou, Nouveaux mémoires sur l’état actuel de son gouvernement, des sciences, des arts, du commerce, de la population & de l’histoire naturelle (six volumes, Dijon & Paris 1766, etc.).

35. Omont (op. cit.), no. 26.

36. The catalogues of manuscripts in the Bouhier library are all inaccessible to the writer; see Albert Ronsin, La bibliothèque Bouhier. Histoire d’une collection formée du xvie au xviiie siècle par une famille de magistrats bourguignons ([Dijon] 1971), pp.106–111.

37. Claude de Novion, chevalier de Malte (11 March 1665), assumed a military career; he was commissioned in 1667 capitaine in the cavalry (Chevau-Légers), and later Brigadier des Armées du Roi.

38. Jacques de Novion, a ‘Docteur en Sorbonne’, became Abbé du Petit-Cîteaux, Bishop of Sisteron (1674), Fréjus (1680), and d’Evreux (1681).

39. A third son, André ii (d. 24 January 1677), who had already commenced his legal career (avocat-général in 1661, maître des requêtes in 1663) and married (1660), is less likely to be the traveller. Sotheby’s sale catalogue, 12–13 October 2010 (op. cit.), p.42, conjectures that their father, Nicolas Potier de Novion, undertook the journey.

40. Charles Févret obtained licenses in civil and canon law from the University of Paris and was received as advocat of the Parlement of Paris on 6 February 1673. Jacques Févret commenced studies of Latin and Greek philosophy in 1670 and ‘quelques années après, il fut receu bachelier de sorbonne’; see Bibliothèque nationale de la France, NAF 4409: ‘Mémoires de la famille Févret’, transcribed and edited by Isabelle Fournet, pp.133–134 (www.ecritsduforprive.fr/biblionum/fournet isabelle/memoires de la famille fevret.pdf). Philibert Papillon, Bibliothèque des auteurs de Bourgogne (Dijon 1742), i, pp.213–215.

41. Pierre Févret studied law at the University of Paris and was received as advocat on 11 January 1684, departing for Italy soon thereafter: ‘a son retour tomba dangereusement malade a aix en provence. ses voyages contribuerent beaucoup a alterer sa santé, qui fut toujours languissante depuis ce temps la’ (Fournet, op. cit., p.137).

42. Pierre Févret was ordained priest in 1655. His first voyage in Italy lasted one year (‘l’an 1661. il fit le voyage d’italie auquel il employa une année’) and the second nearly five months (‘l’an 1692. il fit un second voyage en italie, par les suisses et par la valteline, auquel il employa près de cinq mois’; see Fournet (op. cit.), pp.127, 136. Papillon (op. cit.), i, pp.215–216.

43. Lelong (op. cit.), edited by Barbaud de La Bruyère (Paris 1775), iv, p.489 (recording Dampierre’s possession of the manuscripts). The books were sold by auction: Catalogue des livres du cabinet d’histoire de France de feu Monsieur Fevret de Fontette… dont la vente se fera le lundi 30 Août 1773, & jours suivants, en la manière accoutumée (Paris [1773]).

44. Des Marches (op. cit.), pp.45–46; Delisle (op. cit.), iii, p.375 (cf. i, p.548). The rôle of Pierre Pitois, marquis de Quincy, Seigneur de Saint-Maurice, in the dispersal of the library is opaque.

45. The treatise occurs within the final volume of the ‘Recueil de généalogies’ (Tome v, Portefeuille xxva, f.1–27); see Inventaire des manuscrits de la collection Moreau (op. cit.), p.52 no. 801.

46. Dijon, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms 585 (342): Le conclave d’Innocent onziesme, nommé avant son exaltation Benoist Odescalchi, et l’estat du sacré collège de la cour de Rome. Le pape Innocent onziesme, nommé devant son pontificat Benoist Odescalchi (82 leaves, 217 × 165 mm). Later sections of the manuscript are titled (f.41) ‘Familles de la noblesse de Rome’, (f.51) ‘Tableau du gouvernement de Rome’, (f.69) ‘Estat de la maison du pape’.

47. A catalogue of his gift (compiled by François Oudin) was published: Collegium Divio-Godranium Societatis Jesu, Bibliotheca illustrissimi viri D. Petri Fevreti, in suprema Burgundiae curia senatoris inter clericos primi in Sacra Regia Divionensi Aede cancellarii & Canonici, ipsius testamento Publicata in Collegio Divio-Godranio Societatis Jesu (Dijon 1708).

48. Christine Lamarre, ‘Le Parcours d’un bibliothécaire de l’Ancien Régime à la Révolution: Charles Boullemier, du collège des Godrans à la bibliothèque de l’Ecole centrale de Dijon’, p.5 (www.enssib.fr/bibliotheque-numerique/document-1295).

49. Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, La festa barocca, Corpus delle feste a Roma, 1 (Rome 1997), pp.252–253.

50. Omont (op. cit.), p.29 (‘Andanson’, evidently from the manuscript of Anthelme de Migieu); p.58 (‘Adanson’, from Omont’s index). Andanson and Adanson are variations of Adamson, a family supposedly emigrated from Scotland in the 17th century, of whom the naturalist Michel Adanson (1727–1806) was a celebrity in the 1750s; see J.-P. Nicolas, ‘Michel Adanson et l’Auvergne’ in Comptes rendus du 88° Congrès national des sociétés savantes: Section des Sciences (Paris 1963), pp.57–68.

51. Sotheby’s sale catalogue, 12–13 October 2010 (op. cit.), p.42: ‘Il peut se lire Gudanson ou Oudanson’.

52. Various archival documents relating to Guillaume Cudanson (including a post-mortem inventory, conducted 28 May 1640) are collected by Jean Lecuyer, ‘Cudanson, Guillaume’ (www.geneanet.org); the marriage register of Stains 1549–1898 was digitised by the Cercle généalogique de l’Est Parisien (www.cgep93.org).

53. See Omont (op. cit.), pp.5–6, on the sources of the manuscripts in the De Migieu collection.

![[Anonymous], "Traité du gouvernement civil et ecclésiastique de Rome", subscribed by the copyist, Anthelme-Michel-Laurent de Migieu (height of binding 225 mm)](https://www.robinhalwas.com/2647-small_default/018009-manuscript-diary-of-his-travels-in-italy-1739-1740-with-charles-de-brosses.jpg)