Cornelii Schvt Antverpiensis pictvrae lvdentis genivs, svis natvram seqvens lineis, exprimens elementis, adornans mysteriis: in gvstvm artis, et vsvm, eorvm omnivm qvi elegantias amant, tractant, aestimani

- Subjects

- Book illustration - Reproductive printmaking - Schut, Cornelis, 1597-1655

- Prints - Artists, Dutch & Flemish - Schut, Cornelis, 1597-1655

- Authors/Creators

- Schut, Cornelis, 1597-1655

- Artists/Illustrators

- Schut, Cornelis, 1597-1655

- Other names

- Cantelmo, Andrea, 1598-1645

Schut (Cornelis)

Antwerp 1597 – 1655 Antwerp

Cornelii Schvt Antverpiensis pictvrae lvdentis genivs, svis natvram seqvens lineis, exprimens elementis, adornans mysteriis: in gvstvm artis, et vsvm, eorvm omnivm qvi elegantias amant, tractant, aestimani

Antwerp c. 1632-1654

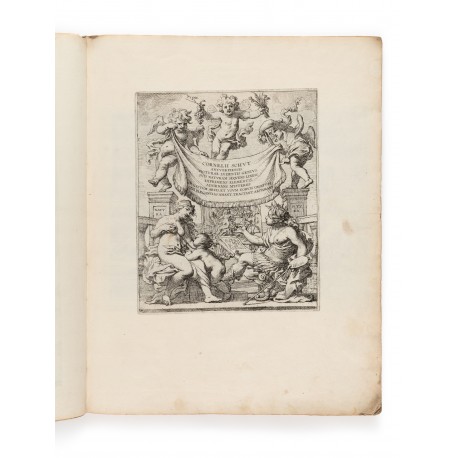

folio (452 × 350 mm), 98 prints imposed on 45 sheets, including ‘title-print’ (transcribed above) and ‘dedication-print’ (to the commander of the Hapsburg armies, Andrea Cantelmo); see album contents below.

watermarks (1) Basilisk with one foot above a house and a Basel crosier in its beak, initials rp below (115 × 75 mm);1 (2) similar mark, initials ic on the side of the house (100 × 80 mm). Watermark in binder’s endpapers: bunch of grapes, lettered in a banner below: i. poylevé (65 × 114 mm).2 See reproductions below (Figs. 1-3).

provenance Fettercairn House, Kincardineshire (probably collected by Sir William Forbes, 6th Baronet of Monymusk and Pitsligo, 1739-1806) − Sotheby’s, Two Great Scottish Collections: Property from the Forbeses of Pitsligo and the Marquesses of Lothian, London, 28 March 2017, lot 153 (part lot; link)

Light soiling to some sheets, few lower corners turned; other minor defects.

binding contemporary flexible vellum (very worn, with losses to vellum).

An album of prints of Cornelis Schut, apparently assembled and marketed by the printmaker himself. It contains ninety-eight plates that he had first sold individually, or in small sets, and has now imposed on forty-five sheets of paper of a uniform large size, with the smaller plates printed in groups of two, three, or four on a single sheet. Several comparable albums are known, with varying contents but similarities in the arrangement of the prints. They are evidence of burgeoning interest among collectors in acquiring the output of single artists, a taste that developed in the 1630s and quickly spread, soon guiding the commercial strategy of numerous printmakers, including Rembrandt.3

Cornelis Schut was a Flemish painter, primarily of ‘history’ (no portraits, landscapes, or still lives by him are known), who applied himself to the production of church altarpieces and to painting religious and profane subject matter for private clients, working with varying degrees of studio assistance. He collaborated with Daniel Seghers in the creation of flower garland pictures, in which he supplied the small scenes decorating the centre of the compositions. Schut also produced cartoons for tapestries, and at least one design for a work in silver, a platter with ewer (aiguière), owned by Rubens. He was prolific: in a recent catalogue raisonné, some 431 paintings are documented.4

Among history painters of his time, Schut was by far the most active printmaker. His oeuvre, as catalogued by Dieuwke de Hoop Scheffer, consists of 203 prints. 5 (Rembrandt, by comparison, made around 300 prints during his career.) More than half of these are small-format prints of Catholic devotional nature, depicting Mary with her Infant Son, Christ on the Column, Saints, and subjects from the Old and New Testament. Many are artless, evidently intended for the mass market, objects for private devotion to be sold to parish churches, religious orders, and confraternities.6 About a quarter feature putti and playing children, compositions useful as models for decorative painters and artisans, and the remainder are subjects from ancient history and mythology, or allegories. One of the prints is dated 1632.7 Surprisingly few prints record the artist’s own paintings.8 Conspicuous variation in quality and in the manner of etching suggest the involvement of multiple hands in their production: the artist himself, studio assistants, and professional printmakers.9

Although Schut infrequently signed his paintings (his collaborations with Seghers were signed by Seghers alone), he scrupulously lettered his prints to indicate his role as draughtsman or ‘inventor’, or to claim both design and execution of the print (invent. et fecit), and to assert copyright (cum priuilegio). This practice suggests that Schut regarded printmaking as a means to increase his own visibility, as well as an additional source of income. The lettering informed buyers that he retained possession of the plate and sold impressions himself. Schut guarded his stockpile of matrices. In 1649, he added a codicil to his will, stipulating that the plates were to be retained as a group, and none sold except at prices approved by his widow.10

Evidence that Schut acted as a publisher, forming and selling his prints as collected oeuvres, is found in an inventory taken in 1664, nine years after his death. The inventory lists some 96 of his copper matrices as well as ‘boecken’, or sets of his etchings: ‘eenen boeck van de geëtste prenten gequoteert’ (no. 32) and ‘eenen geëtsten printboeck’ (no. 33).11 Ger Luitjen interprets these two inventory entries as referring to ready-made albums, which Schut had assembled for a new type of collector, who sought the oeuvre of an artist rather than specific subjects.12

Four such albums were identified by Luijten. Each contains an allegorical ‘title-print’ representing Nature feeding her infant, while Pictura executes a painting based on the classical phrase ‘Veritas filia temporis’; eight lines in Latin above proclaim Schut’s intentions.13 Also present in each album is an allegorical ‘frontispiece’ representing the heraldic insignia of Andrea Cantelmo (1598-1645), governor of the army of the Low Countries, who was the probable patron of the tapestries series of ‘The Seven Liberal Arts’ woven repeatedly in the workshop of Carolus Janssens, Bruges, from cartoons supplied by Schut.14

In our album and in the album in the Stedelijk Prentenkabinet, Antwerp, the ‘title-print’ follows the ‘frontispiece’, and the next four prints are in identical order; thereafter, the arrangement of plates in the two albums diverge.15 Both albums, however, are printed on similar paper stock (watermark of a Basilisk with one foot above a house and a Basel crosier in its beak, the initials RP suspended below; see figs. 1-2).16 Among plates included in the Antwerp album, but lacking in ours, is a ‘closed’ series of prints, the ‘The Seven Liberal Arts’ (title and seven prints), and title-prints from two ‘open-ended’ series: ‘Varie capricci di Corneli Schut’ and ‘Livres d’enfans poséz en racourcissant inventé et gravé en eaux-forte par Cornelius Schut’.17 The album in the National Gallery of Art lacks four of the ‘Liberal Arts’ series.18

Fig. 1 Basilisk with one foot above a house and a Basel crosier in its beak, initials rp below (115 × 75 mm). Reproduced from ■ [34]

Fig. 2 Similar mark, initials ic on the side of the house (100 × 80 mm). Reproduced from ■ [39]

Fig. 3 Watermark in binder’s endpaper, banner lettered: i. poyleve (65 × 114 mm)

Sometime after 1664, the group of copper matrices described in the notarial inventory was distributed to publishers, and no similar collections of Schut’s prints could be issued. The new owners of Schut’s matrices, of whom the publishers J. Haest,19 Johannes Meyssens,20 Franciscus vanden Wijngaerde,21 and Cornelis Galle in Antwerp,22 and perhaps Abraham van Waesberghe in Rotterdam,23 are known, often strengthened details in the plates with the burin, and added their names in the matrice.

comparable albums

Several of the albums listed below contain prints by printmakers other than Schut, and thus may be later arrangements with prints added from other sources.

- Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentenkabinett (link)

Provenance: Guillaume Huijmans (Cornelis Schut’s son-in-law, c. 1625-1687) – Pieter Cornelis Baron van Leyden van Vlaardingen (1717-1788), acquired with the latter’s collection by the Dutch State in 1807, in the Rijksmuseum since 1816.24

Once ‘un livre Grand in Folio, relié en Cuir de Russie & doré sur Tranche’, the album was broken up by the museum. - Antwerp, Stedelijk Prentenkabinet (Museum Plantin Moretus), PK.OPB.0222.000-137 (link)

‘Bundel met 136 (deels) handgenummerde prenten met daarop afbeeldingen (o.a. Borias en Eurythia, Neptunus met twee paarden in de zee, putti’s en cherubijntjes) van verschillende onderwerpen’ (link).

Folio 135 in the series is unrelated (‘Portret van François Eugene van Savoye’, by Pieter van Gunst). - Brussels, Royal Library, H.H. 9.377 B (link)

Provenance: Charles Joseph Emmanuel van Hulthem (1764-1832) – acquired by the Belgian State in 1837. Bibliotheca Hulthemiana; ou, Catalogue méthodique de la riche et précieuse collection de livres et des manuscrits délaissés par M. Ch. van Hulthem (Ghent 1836-1837), II, p.181 no. 9377: ‘En 1 vol. in-fol. d. rel. Contenant 119 gravures montées avec soin’ (link). - New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1970.573.1-176 (link)

Provenance: manuscript title ‘Het eigengeetste werk van Cornelis Schut en anderen bestaande in veelerlei bijbelsche figuren’ – with R.E. Lewis (c. 1970).

‘Scrapbook of 176 etchings by or after Schut’ (62 × 47 cm), bound (c. 1820-1850) in the shop of the London binder ‘T[homas] Armstrong’. - Washington, dc, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund 1973.62.1-150 (link)

Provenance: George Paget – Christopher Mendez, ‘Catalogue 26: Old Master prints’ (London 1973), p.37 item 25 (£500). 25

‘Album of Cornelis Schut etchings and engravings’, 148 plates, including plates after Schut. - unlocated: sold 1714: anonymous owner

Abraham de Hondt, Catalogus Bibliothecae Luculentissimae, & Exquisitissimis ac rarissimis in omni Disciplinarum & Linguarum genere libris, magno sumtu, dilectu, & studio quaesitis, instructissimae… Ad diem 9. [-17] Aprils 1714 (The Hague 1714), p.40 lot 482: ‘Picturae Ludentis deliciae & Paradigmata, delineata & incisa a Corn. Schut, in 95 Tabulis elegantissimis, nitid. compact. Ch. Maj. Exemplar exquisitum’ (link). - unlocated: sold 1805: Gottfried Winckler (1731-1795)

Michel Huber and J.G. Stimmel, Catalogue raisonné du cabinet d’estampes de feu monsieur Winckler… Contenant une collection des pièces anciennes et modernes de toutes les écoles, dans une suite d’artistes depuis l’origine de l’art de graver jusqu’à nos jours : Tome troisième (Leipzig 1805), pp.974-978: ‘un recueil de cent trente-trois estampes de divers sujets et de différentes grandeurs’ (entries 5373-5411; link). - unlocated: sold 1817: Louis Maximilien comte Rigal (1748-1830)

François Léandre Regnault-Delalande, Catalogue raisonné des estampes du cabinet de m. le Comte Rigal (Paris 1817), p.339 no. 745: ‘La Peinture ayant pour objet la Nature en peignant la Vérité, frontispice avec huit lignes d’inscription: Cornelii Schvt Antverpiensis… Aestimant, gravé à une draperie que tiennent deux génies ailés; au-dessus, dans les airs, Zéphire, des fleurs et des fruits à la main; différens sujets de l’Ancien et du Nouveau Testament : dans ce nombre, David coupant la tête à Goliath; Judith prête à couper la tête à Holopherne, Suzanne au bain, l’Annonciation, la Visitation, la Nativité; des Sujets de la Vie et de la Passion de Notre-Seigneur, autres de Saintes-Familles et de Vierges; La Conversion de saint Paul; saint Laurent et saint George martyrisés; saint Ignace changeant de vêtement avec un pauvre; Vénus, Bacchus et Cérès; l’Enlèvement d’Europe, Borée enlevant Orithye, Pirame et Thisbé; le Triomphe de la Paix ; les Arts libéraux; Suite d’Enfans, autres de divers Caprices, etc. 171 Estampes, la plupart très-petites’ (link). - unlocated: sold 1827: Johann Christoph Freiherr von Aretin (1772-1824)

François Brulliot, Catalogue raisonné des estampes du cabinet de feu Mr. le Bar. d’Aretin, Conseiller d’État et Ministre de S.M. le Roi de Bavière à la Diète de Francfort… Tome premier contenant l’École Allemande et celle des Pays-Bas… le 5. Juillet 1830 et les jours suivants (Munich 1827), pp.374-377 lots 3977-4003 (link). - unlocated: offered c. 1837-1849: Rudolph Weigel

Rudolph Weigel, Kunstkatalog. Erste Abtheilung mit Nachtrag. Dritte berichtigte Auflage (Leipzig 1849), p.24 no. 277: ‘Das Werk des Malers Cornelius Schut, Rubens Schüler. 176 geistreich radirte Blätter, in verschied. Grössen. Das Titelblatt: Cornelii Schutt Antv. Picturae ludentis genius etc. Auf schönen braunen Untersetzbogen in einer Mappe in gr. fol. 10 [Thlr]’ (link).26

This possibly is the volume now in New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. - unlocated: sold 1856: Joan Quarles van Ufford (1821-1856)

Martinus Nijhoff, Catalogus eener belangrijke en uitgezochte verzameling boeken over alle vakken van wetenschap, kunst en smaak… Meerendeels nagelaten door… Jhr. Mr. J. Quarles van Ufford, Referendaris aan het Ministerie van Binnenlandsche Zaken (Afd. Waterstaat) en Jhr. Mr. H.G. Quarles van Ufford, waarvan de verkooping zal plaats hebben op Maandag, 3 [-7] November 1856… dooren ten huize van Martinus Nijhoff, Boekhandelaar (The Hague 1856), p.75 lot 273: ‘Un vol. gr. in-fol. cont. sur 86 feuilles plus de 200 gravures et eaux fortes de C. Schut. Belle collection très bien conservée. 1 vol. en veau.’ (link). - unlocated: sold 1862: Johann Andreas Boerner (1785-1862)

Rudolph Weigel, Catalog der Börner’schen Kunstsammlung, oder der von dem allbekannten Kunstkenner Johann Andreas Börner, Buch- und Kunst-Auctionator zu Nürnberg hunterlassenen Sammlung… deren erste Abtheilung die Niederlandische Schule enthaltend… 22. Januar 1863 und folgende tage (Leipzig 1862), p.51 lot 933: ‘C. Schut. 27 Bl. Heilige und andere Darstellungen nebst dem Titel mit der Dedication an D. And. Cantelmo. In verschiedenem Format’ (link). - unlocated: sold 1927: Christoph Wenzel von Nostiz-Rieneck (1649-1712)

C.G. Boerner, Sammlung des Reichsgrafen Christoph Wenzel von Nostiz-Rieneck (1649-1712) : Porträt-Sammlung des Sir Alfred Morrison, London († 1897) : Versteigerung… vom 10. bis 12. November 1927 (Leipzig 1927), p.193 lot 1769: ‘Ca. 50 Bl. mit ca. 139 radierten Darstellungen, dabei ein Titel und ein Widmungsblatt. Verschiedene Formate. Einige Bl. lose… Ausgezeichnete Abdrucke, einige wenige leicht verschnitten. Dabei zwei Bl. nach Sch.’ (link).

In this catalogue, item nos. 1685-1778 comprise the ‘Dritte Abteilung: gebundene Folgen und Bücher: Der größte Teil der Bände ist in altes Pergament gebunden, weshalb meist von einer Einbandbeschreibung abgesehen wurde’.

album contents

Folio 1

- [1] Two Lions Holding Flags and a Lion Coat of Arms surmounted by an Eagle. Below, a dedicatory cartouche flanked by Harpies; lettered (11 lines): illvstrissimo et excellentissimo d. andreae cantelmo, sangvine regio, nec sva minvs virtvte ad belli gloriam nato, exercitvvm svmmo cvm imperio dvctori, poliorcetae belgico, qvi salvtem, secvritatem, fidvciam, lvcembvrgo, flandriae, brabantiae dedit, svisqve potissimvm consiliis, et armis victoriam calloanam peperit, heroi inter arma elegantias colenti, [below, in 3 lines: ] has pictvrae lvdentis delicias cornelivs schvt anverpiensis manv, mente, mvnere d.c.q.

Etching, 412 × 274 mm.

Hollstein 149. Nagler 660 (‘Dieses Titelblatt haben wir nicht gesehen’).27 Luitjen, op. cit., p.142.

Other impressions Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.274 (link); National Gallery of Art, 1973.62.2 (link); Lisbon, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, E. 855 V. (link)

The lettering on the print is reproduced in Carlo de Lellis, Discorsi delle famiglie nobili del Regno di Napoli (Naples 1654), p.151 (link).

Folio 2

- [2] Allegory of Nature and Painting: Nature with a child standing at left, Painting seated at right, holding a pallet and brushes; three putti above holding a draped curtain, lettered (8 lines): cornelii schvt antverpiensis pictvrae lvdentis genivs, svis natvram seqvens lineis, exprimens elementis, adornans mysteriis: in gvstvm artis, et vsvm, eorvm omnivm qvi elegantias amant, tractant, aestimani

Etching, 266 × 215 mm.

Hollstein 137 (as 226 × 215 mm). Luitjen, op. cit., pp.140-141 Afb. 7 (Rijksprentenkabinet, as 226 × 215 mm). Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’, op. cit., 8.4 and Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 32 (Brussels, Inv. No. 89899, fº, as 267 × 216 mm).

Other impressions Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.275 (link); National Gallery of Art, 1973.62.1 (link); British Museum, 1929,0114.8 (link)

Folio 3

- [3] Vulcan’s Forge: Venus and Cupid standing at right, Cupid shooting an arrow in the sky, Vulcan behind an anvil at centre, assisted by four men, a canon and armour in foreground

Etching, 246 × 323 mm. Signed in lower margin, at left: Cornel: Schut inu. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 121.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.412 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.265 (link)

The print reproduces a scene from a fresco cycle painted by Schut c. 1624-1627 for the piano nobile of the Casino Pescatore, Frascati (Wilmers, op. cit., pp.64, 341 nos. A1 and A1a; Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., p.102 fig. 70).

Folio 4

- [4] Ceres standing in a landscape and holding a cornucopia, a woman and a young girl next to her, two satyrs offering grapes and fruits at right, another satyr seen from behind in lower left

Etching, 245 × 325 mm. Signed in lower margin, at left: Corn: Schut inuen: Cum priuilegio

Hollstein 119.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.411 (link) and 1929,0114.16 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.268 (link)

Folio 5

- [5] Neptune drawn by two seahorses at centre, Amphitrite (?) at left, three putti in top centre

Etching, 244 × 325 mm. Signed in lower margin, at left: Cornelius Schut inuent. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 124 (244 × 314 mm).

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.406 (lower margin cut, link) and 1929,0114.32 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.269 (link); National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1972.28.94 (link)

Folio 6

- [6] Boreas and Oreithyia; the wind-god abducting the girl, flying towards left, two blowing putti on either side

Etching, 242 × 328 mm. Signed in lower margin, at left: Cornelius Schut inu. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 115.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.17 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-103.391 (link)

Folio 7

- [7] Pyramus and Thisbe: Thisbe kills herself with Pyramus’ sword

Etching, 178 × 232 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuen : cum priuilegio

Hollstein 113. Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’, op. cit., 8.1 (citing a copy in reverse).

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.261 (link)

Folio 8

- [8] Pyramus and Thisbe: Pryamus lying dead, turned to left, Thisbe lying on his chest; in a landscape with a fountain on the right, a lion in left background

Etching, 179 × 235 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 114. Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’, op. cit., 8.2.

Other impressions British Museum, 1982,U.3983 (cropped, link) and 1870,0514.1269 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.260 (link)

Folio 9

- [9] Bacchus, Venus and Ceres (sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus)

Etching, 274 × 208 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuent: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 118.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1882-A-6266 (link)

Folio 10

- [10] Frieze with eight bacchants

Etching, 100 × 330 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inue: cum priuileg:

Hollstein 155/II.

An impression in first state (before Schut’s name) is reported in Munich.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.287 (link)

- [11] Frieze with seven putti around a basket with fruit, one holding a broken branch, a cherub at left, two children playing with a fruit garland at right, a sleeping child in top right corner

Etching, 101 × 329 mm. Signed within image lower left corner: Cornelius Schut inu: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 156.

Other impressions British Museum, 2013,7011.1 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.288 (link)

Folio 11

- [12] Frieze with six putti, seemingly being blown away by an unidentified force, a globe at centre

Etching, 90 × 335 mm. Signed within image, in lower left: Cornelius Schut inu. Cum priuilegio

Hollstein 153/II.

An impression in first state (before Schut’s name) is reported in Munich.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.36 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.283 (link)

- [13] Frieze with five playing children, one holding a bird on a string at left, Bacchus holding a bunch of grapes at centre, two cherubs at right

Etching, 101 × 328 mm. Signed within image, at left: C. Schut in. cum priui.

Hollstein 157/II.

An impression in first state (before Schut’s name) is reported in Munich.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.439 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1951-708 (link)

Folio 12

- [14] Three children with a dog in a landscape

Etching, 128 × 224 mm. Signed in lower margin, at left: Cornelius Schut inuen: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 161.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.278 (link)

For a copy in reverse, see British Museum, 1878,0112.291 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1883-A-6987B (link)

- [15] Eight children playing blind man’s buff

Etching, 130 × 225 mm. Signed in lower margin, at left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 158. Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’, op. cit., 8.6

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.35 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.277 (link)

For a copy in reverse, see British Museum, 1878,0112.293 (link)

Folio 13

- [16] Frieze with nine children engaged in different activities, some hanging garlands, one with bow and arrow

Etching, 112 × 347 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 154.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.37 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.284 (link)

Folio 14

- [17] Four children; in the centre, one child is sitting on a swing while another moves the swing; two children are sitting on the right, one holding a bunch of grapes

Etching, 134 × 168 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 159. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 49 (Brussels, Inv. no. 89977, fº).

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.26 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.290 (link)

For a copy in reverse, see British Museum, 1878,0112.289 (link) - [18] Frieze with five children, in the centre a caduceus, globe, and armillary sphere

Etching, 63 × 293 mm. Signed on the globe: Corn: Schut inu. cum priu

Hollstein 152/II.

An impression in first state (before Schut’s name) is reported in Munich.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.282 (link)

Folio 15

- [19] Four children, one child sitting on a swing; another one moves the swing; two children sitting on the right

Etching, 100 × 130 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn Schut in. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 160. Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’, op. cit., 8.8.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2226 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.292 (link) - [20] Five bacchants: the one at left pulls the plug of a wine-cask

Etching, 99 × 202 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inu cum priuileg

Hollstein 162. Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’, op. cit., 8.7.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.291 (link)

For a copy in reverse, see British Museum, 1878,0112.292 (link) and 1872-10-12-3477 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1883-A-6987C (link)

Folio 16

- [21] Susanna and the Elders; the elders behind her at right, a dolphin-fountain spouting water at left

Etching, 143 × 140 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inuen cum priuilegio

Hollstein 4.

Other impressions British Museum, 1878,0812.2194 (link) and 1878,0713.4723 (later impression, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.180 (link) - [22] Susanna and the Elders; Susanna on the left, bending over, resting on the fountain; one elder behind her, the other on the right near a fountain

Etching, 146 × 131 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 3/II.

Impressions in first state (before Schut’s name) are in Amsterdam (RP-P-1882-A-6258, link) and Leiden.

Other impressions (second state) British Museum, 1878,0713.4722 (link) and 1871,0812.2193 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.179 (link)

For a copy in reverse by Michael Willmann, see British Museum, S.5599 (link).

For the lost painting, recorded in a painting by David Teniers the Younger (Raby Castle, County Durham), see Wilmers, op. cit., p.147 nos. A82 and A82a; Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., pp.99-100; Sotheby’s, Old master paintings, 7 July 2004, lot 24 (link).

Folio 17

- [23] Two putti in a landscape, on either side of a lamb, feeding it with some fruit

Etching, 85 × 110 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuent: cum priuileg

Hollstein 164.

Other impressions British Museum, 1874,0808.984 (77 × 109 mm, inscriptions cut off, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.315 (link) - [24] The Christ Child, blessing, sitting on clouds, flanked by angels; in His right hand the cross of the resurrection with a banner

Etching, 70 × 55 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 22.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.417 ( link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.195 (link) - [25] Virgin and Child sitting on the clouds, in front view, heads of angels above

Etching, 68 × 60 mm. Signed in left corner below: CS in ; at right: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 32.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.427 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.193 (link)

Folio 18

- [26] Two children, one with a bunch of grapes, the other with a dish

Etching, 74 × 95 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inu. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 185.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.316 (link) - [27] Two children, one seen from the back, his right hand on the other’s belly

Etching, 71 × 95 mm. Signed in margin below, left: C. Schut inu cum pri ; and: Primauera

Hollstein 186.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.317 (link)

Folio 19

- [28] Three boys near a fire, one warming his hands

Etching, 74 × 106 mm. Signed lower right: CS in. cum priuileg

Hollstein 184.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.314 (link) - [29] Two boys in a landscape, one picking some fruit

Etching, 71 × 100 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn. Schut inu. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 183.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.313 (link)

Folio 20

- [30] The Christ Child and Infant Saint John the Baptist, sitting, embracing each other

Etching, 65 × 50 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut in. cum priuil.

Hollstein 28 (as 58 × 50 mm).

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.201 (link) - [31] The Christ Child and Infant Saint John the Baptist, Christ sitting on the right, the Cross in His left hand

Etching, 66 × 50 mm. Signed in margin below, left CS inu ; at right: Io Son Del Tempo 1632

Hollstein 25.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.199 (link) - [32] The infant Saint John the Baptist, kneeling to the right near a small stream, in his left hand a tray, the lamb on the left

Etching, 54 × 49 mm. Signed in lower left corner: CS

Hollstein 30.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.9 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.196 (link) - [33] The infant Saint John the Baptist, sitting on a stone near a small well, the lamb to the right, in his hand a little tray

Etching, 52 × 47 mm. Signed with the monogram between Saint John’s feet: CS

Hollstein 29.

Other impressions British Museum, 1869-06-12-548 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.197 (link)

Folio 21

- [34] Christ Child sitting on clouds, the Cross in His left hand, blessing

Etching, 71 × 50 mm. Signed in margin below, left: CS in cum priuilegio

Hollstein 21 (as signed: CS cum priuilegio).

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.200 (signed: CS in cum priuilegio, link) - [35] Christ Child as Salvator Mundi, siting on clouds, orb in His right hand

Etching, 72 × 45 mm. Signed in margin, bottom left: CS in ; San Salvator

Hollstein 20.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1888-A-12898 (link) - [36] Allegory of Vanity: a child blowing bubbles, behind him, on the right, is an hourglass; at left is a skull

Etching, 63 × 52 mm. Signed bottom left: CS in

Hollstein 147.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.25 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.300 (link) - [37] Allegory of Vanity: a child blowing bubbles, behind him, on the left, is an hourglass; below is an overturned wine cup

Etching, 71 × 54 mm. Signed bottom left: CS in cum priuilegio

Hollstein 146.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.319 (link)

Folio 22

- [38] Air; a child sitting on a plough, riding on the clouds, fruit and ears of corn in his arms; part of a series of ‘The Four Elements’

Etching, 72 × 106 mm. In margin below, left: Corn: Schut inuentor cum priuileg:

Hollstein 141.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.305 (link) - [39] A child, sitting left of a gun; bullets in foreground left; fire in the background

Etching, 74 × 104 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 174.

Other impressions British Museum, 1859,0611.155 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.320 (link)

For the same subject in reverse (Hollstein 174a), see British Museum, 1929,0114.29 (link) - [40] Water; a child, sitting, turned left; taking a fish from a fishing-rod; behind him a large jar; part of a series of ‘The Four Elements’

Etching, 69 × 95 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 139.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2236 (link) and 1871-8-12-2235 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.309 (link)

For a smaller copy in reverse (Hollstein 143), see British Museum, 1871,0812.2237 (42 × 52 mm, link) - [41] Three flying putti

Etching, 72 × 97 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 151.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.310 (link)

Folio 23

- [42] A putto with a wreath of flowers in left hand, in right hand a palm; in the clouds; another angel with a flute below and a cherub on the left

Etching, 65 × 100 mm. Signed in top corner: C. Schut in. cum pri

Hollstein 176.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.30 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.324 (link) - [43] Two naked children near a gun; the child on the right sets gunpowder on fire; a building in the background left

Etching, 74 × 93 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 172.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.28 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1888-A-12901 (link) - [44] Fire; a sleeping child, sitting, turned right near a fire, next to him a pair of bellows; part of a series of ‘The Four Elements’

Etching, 74 × 92 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuen: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 140.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2222 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-103.392 (link) and RP-P-OB-59.311 (link) - [45] Earth; a naked child, sitting, turned right; in left hand a shovel, in right hand fruit and ears; part of a series of ‘The Four Elements’

Etching, 67 × 92 mm (upper right corner clipped). Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 138.

Other impressions (both likewise clipped) British Museum, 1871,0812.2227 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.323 (link)

The copper matrice is in the Royal Library of Belgium (Chalcography KBR, A447); Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., p.236.

Folio 24

- [46] Four children, one skipping rope, another at left wearing a helmet and carrying a banner

Etching, 72 × 62 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inuent cum priuilegio

Hollstein 190.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.302 (link) - [47] Three playing children; the right one kneeling to the left, the two others wrestling; in foreground right a croquet ball and stick

Etching, 73 × 63 mm. Signed in margin below, left: C. Schut inu. cum priuileg

Hollstein 192.

Other impressions British Museum, 1859,0611.164 (link) and 1871,0812.2228 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.304 (link)

Folio 25

- [48] Virgin and Child in a cartouche framed by putti

Etching, 263 × 224 mm. Signed in margin left: C: Schut in: Cum Priuilegio ; below: Benedicta Tv in Mvlieribvs

Hollstein 36.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.222 (link)

Folio 26

- [49] Virgin and Child with Saint John in a landscape. Saint John on the left, holding with left hand the right foot of the Child, a lamb behind Saint John, two angels and one cherub in top corners, two angels in a tree on the left

Etching, 287 × 210 mm. Signed in margin below the image, left: Corn: Schut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 79/II.

The first state is only known from a counterproof before Schut’s name in Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1951-705 (link). Copper matrice (292 × 211 mm) in Antwerp, Stedelijk Prentenkabinet, PK.KP.01054 | KP V/55 (link).

Other impressions (second state) British Museum, 1983,U.421 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.221 (link)

A related black chalk drawing is in the National Gallery of Art, Julius S. Held Collection, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund 1984.3.60 (link).

Folio 27

- [50] Virgin and Child with Saint John, sitting in frontal view in a landscape, Saint John kneeling on the right, his left arm on the lamb, a cherub with a wreath of flowers above

Etching, 218 × 157 mm. Signed in the margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuileg

Hollstein 82/I.

The second state of this print has added address: à Anvers chez J. Haest (Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-103.399, link).

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.438 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.240 (link)

Folio 28

- [51] Virgin and Child with Saint John in a landscape, Saint John kneeling on the right, touching the right foot of the Child, a banner in right hand

Etching, 206 × 170 mm. Signed in margin below the image, left: Corn. Schut inuen. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 80.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.420 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.239 (link)

For an associated drawing (Hamburg, Kunsthalle), see Wilmers, op. cit., p.430 figs. 20-21.

Folio 29

- [52] Virgin with Child sitting, half-length and turned to the right

Etching, 132 × 100 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inuen: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 40.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.431 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.219 (link) and RP-P-OB-59.223 (link) - [53] The Virgin and the Child with Saint John and the lamb on the left, the child with a bunch of grapes in His left hand, the two Children sitting on a pedestal, turned to left

Etching, 115 × 200 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn. Schut inue cum priuilegio

Hollstein 75.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.418 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.211 (link)

Folio 30

- [54] Virgin, the Child and Saint John with the lamb, a truncated column on the left with a branch of roses

Etching, 130 × 86 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuen: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 74.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2207 (link) and 1983,U.415 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.202 (link) - [55] Virgin with Child on her lap, sitting half-length, turned to right but head turned to the left, the Child’s hand on right shoulder of the Virgin

Etching, 144 × 96 mm. Inscription in margin, below: Amor Dei ; signed below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 33/I.

Publication details are added in the second state: à Anvers chez J.Haest.

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.430 (cropped, indeterminate state; link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.203 (link) - [56] Virgin with Child; sitting and turned to right, right arm on a table with a vase of roses

Etching, 140 × 138 mm. Signed in lower margin, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 35.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2205 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.204 (link)

Folio 31

- [57] Holy Family, half-length, near a table, Joseph’s hand on a basket, a bunch of grapes in the Virgin’s left hand

Etching, 90 × 106 mm. Signed in the margin below, left: Corn: Schut inuen: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 83.

Other impressions British Museum, 1859,0611.157 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.205 (link) - [58] Virgin and Child turned to left, a column on the left

Etching, 72 × 93 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inuen: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 71. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 42 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89911, fº).

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2199 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.209 (link) - [59] Virgin and the sleeping Child, on the right Saint John with the Cross

Etching, 63 × 108 mm. Signed in the image, upper left: Corn. Schut inu. Cum priuilegio

Hollstein 77.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.174 (link)

Folio 32

- [60] The Holy Family, turned to right, Saint John on the right with the Cross and an apple in his left hand

Etching, 101 × 71 mm. Signed in the margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 86 (as 98 × 109 mm).

Other impressions British Museum, 1869,0612.545 (as 99 × 70 mm, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.214 (as 109 mm × 98 mm, however image identical; link) - [61] Virgin and Child sitting on clouds, turned to left, the Virgin with a large mantle

Etching, 95 × 55 mm. Signed in top corner, right: Cornel: Schut in: cum priuil:

Hollstein 42.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2195 (link) and 1869,0612.547 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.224 (link) - [62] Virgin and Child, half-length and turned to left, a balustrade behind, the Child with apple in left hand

Etching, 80 × 64 mm. Signed in margin, below: C. Schut in: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 61.

Other impressions British Museum, 1859,0611.161 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.237 (link) - [63] Virgin and Child, in the Child’s right hand the Crown of Thorns

Etching, 98 × 71 mm. Signed in margin, left: Cornelius Schut inuen cum priuilegio

Hollstein 39.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.217 (link)

Folio 33

- [64] Virgin and Child, turned right, behind a balustrade

Etching, 122 × 103 mm. Signed in margin, left: Corn: Schut in cum priuilegio

Hollstein 48/I.

The second state of this print has added address: à Anvers chez J. Haest

Other impression Rjksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.175 (link) - [65] Virgin and Child, sitting and turned to right, the Virgin holds a rose in her right hand

Etching, 127 × 103 mm. Signed in top corner left: Cornel: Schut in ; in top corner right: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 44/II.

An impression in first state before Schut’s name is reported in Munich.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2203 (link) and 1983,U.435 (damaged, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1951-710 (link)

Folio 34

- [66] Virgin with Child lying on her lap, sitting half-length, turned to left

Etching, 118 × 112 mm. Signed in margin, left: Cornel Schut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 34/I (as 121 × 104 mm).

The second state of this print has publication line: à Anvers chez J. Haest.

Other impression British Museum, 1983,U.429 (cropped, indeterminate state; link) - [67] The Virgin and Child on the left, Saint John on the right with Cross and banner, an apple in his left hand

Etching, 68 × 95 mm. Signed in margin below the image, left: Corn: Schut inuen: cum priuilegi.

Hollstein 78.

Other impression British Museum, 1871,0812.2206 (link) - [68] The Christ Child and Saint John sitting with the lamb between them, holding a cross with a banner, lettered: Ecce Angnus

Etching, 47 × 76 mm. Signed in top right corner: A CS chut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 27. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 37 (Brussels, Inv. No. 89919, fº).

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2210 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.198 (link)

Folio 35

- [69] Virgin and Child, half-length and turned to right, the left hand of the Child on the Virgin’s bosom

Etching, 135 × 100 mm. Signed in margin, below: Cornelius Schut inuen. cum priuilegio

Hollstein 57. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 39 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89903, fº).

Other impressions British Museum, 1983,U.433 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1883-A-6983 (link) and RP-P-OB-59.234 (cropped, link)

For the same subject in reverse, see British Museum, 1983.U.432 (link) - [70] Virgin and Child, half-length and turned to left, the Virgin’s left hand in the lap of the sitting Christ, His right hand lifted

Etching, 74 × 63 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 62. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 40 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89903, fº).

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2197 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.238 (link) - [71] Virgin and Child, the Virgin’s right hand holding the right foot of the Child

Etching, 90 × 65 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 43 (as 97 × 63 mm). Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 41 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89903, fº).

Other impression Rjksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.225 (link)

Folio 36

- [72] Virgin, half-length, turned to right, the Child turned left

Etching, 111 × 79 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 41(as 98 × 71 mm).

Other impressions British Museum, 1869,0612.549 (111 × 79 mm, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.220 (link) - [73] Virgin and Child, sitting and turned to right, the left hand of the Child on Virgin’s left shoulder

Etching, 100 × 70 mm. Signed in margin below: Cornelius Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 69.

Other impressions British Museum, 1869,0612.546 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.206 (link) - [74] Virgin and Child, half-length in profile to left, both hands of the Child on the Virgin’s neck, his leg lifted

Etching, 95 × 70 mm. Signed in margin below: Cornel: Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 60. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 38 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89910, fº).

Other impressions British Museum, 1912,0513.22 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.236 (link)

Folio 37

- [75] Virgin and Child; the Virgin’s left cheek against the Child’s head, his left hand lifted

Etching, 63 × 71 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 66. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 43 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89921, fº).

Other impressions British Museum, 1874,0808.933 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1939-172 (link) and RP-P-OB-59.168 (link) - [76] Virgin and Child turned right, the Virgin’s right hand holding the Child’s right foot

Etching, 70 × 98 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 58.

No impression in British Museum or Rijksmuseum; impressions in Antwerp, Brussels, Leiden are located by Hollstein

Folio 38

- [77] Virgin and Child, the Child on the right, lying on a cushion

Etching, 45 × 66 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 52.

Other impressions Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1951-707 (45 × 67 mm, link) and RP-P-OB-59.233 (45 × 57 mm, link) - [78] Virgin and Child, half-length and turned to left, the right hand of the Child on Virgin’s right shoulder

Etching, 43 × 70 mm. Signed in top left corner: C. Schut in cum priuil

Hollstein 55.

Other impressions British Museum, 1912,0513.23 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.231 (link) - [79] Virgin and Child, turned right, the right hand of the Child on Virgin’s left shoulder

Etching, 56 × 56 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 67.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.166 (link); a counterproof is in the British Museum, 1983,U.434 (link) - [80] Virgin and Child, turned right

Etching, 45 × 49 mm. Signed in upper left corner: C. Schut in.

Hollstein 64.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.164 (link)

Folio 39

- [81] Virgin and Child, the Virgin bending over the sleeping Child, His hands on His breast

Etching, 97 × 70 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn: Schut inu: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 50.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.228 (link) - [82] Virgin and Child, sitting half-length and turned to right, the Virgin’s right hand picks an apple from a tree

Etching, 100 × 75 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornel: Schut inuen: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 70.

Other impressions British Museum, 1871,0812.2196 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.207 (link) - [83] The Virgin bending backwards, the Child with His head against her left cheek

Etching, 65 × 48 mm. Signed in image, right: CS inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 68. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 44 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89943, fº).

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.169 (link) - [84] Virgin and Child, the right hand of the Child on the Virgin’s chin

Etching, 67 × 62 mm. No lettering.

Hollstein 65.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.167 (link)

Folio 40

- [85] Virgin and Child, sitting on the clouds, in the right hand of the Virgin a bunch of grapes

Etching, 95 × 70 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 63 (as 81 × 69 mm).

Other impressions British Museum, 1869,0612.550 (69 × 61 mm, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.171 (81 × 69 mm, link) - [86] Virgin and Child, in the Child’s left hand a bunch of grapes

Etching, 97 × 69 mm. No lettering

Hollstein 49/I.

A second state signed by Schut is cited by Nagler.28

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.227 (link)

The copper matrice in the Royal Library of Belgium (Chalcography KBR A439); reproduced by Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., p.236 fig. 56a. - [87] Virgin and Child, the left hand of the Child holds the Virgin’s right forefinger

Etching, 92 × 70 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuent cum priuilegio

Hollstein 51.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.229 (link)

Folio 41

- [88] Christ at the Column, turned to left, both hands bound to the column

Etching, 99 × 57 mm. Signed in margin below: Corn: Schut inuent: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 11. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 35 (Brussels, Inv. S II 89952, fº).

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.189 (link) - [89] Christ, standing, bound to the column, the Crown of Thorns in foreground

Soft-ground etching, 98 × 74 mm, using vernis mou. Signed upper left: CSA (Cornelis Schut Antwerpiae) ; signed in margin below: Cornelius Schut inuent cum priuilegio

Hollstein 15. Diels, Shadow of Rubens, op. cit., pp.217-218 and fig. 23.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.188 (link) - [90] Christ, bound to the column, half sitting and bending to the left

Etching, 123 × 82 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Cornelius Schut inuent: cum priuil.

Hollstein 14.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.12 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.186 (link) - [91] Christ standing at the column, turned to left and leaning on the column, his hands bound on his back

Etching, 97 × 74 mm. Signed below the image, right: CS inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 12.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.10 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.187 (link)

Folio 42

- [92] Crucifixion, with Saint John left), Mary Magdalene (right), and two female disciples

Etching, 108 × 66 mm. Signed in margin below, left: Corn Schut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 18.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.176 (link) - [93] Christ at the column, kneeling to right, both hands bound to the column

Etching, 95 × 76 mm. Signed in the margin below, left: Corn Schut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 16. Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., fig. 48 (Brussels, Inv. no. S II 89950).

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.13 (incorrectly identified as Hollstein 11, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.191 (link) - [94] Christ at the Column, kneeling to left, his hands bound behind his back, the instruments of flagellation at left

Etching, 95 × 71 mm. Signed in margin below: Corn: Schut inuent cum priuilegio

Hollstein 13.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.11 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.190 (link)

Folio 43

- [95] The Christ Child, blessing, Orb in his right hand (Salvator Mundi)

Etching, 103 × 66 mm. Signed in margin below, left: C. Schut inu cum priuilegio

Hollstein 19.

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.194 (link) - [96] Saint Michael, in an oval, his left foot on the dragon

Etching, 90 × 65 mm. Signed in margin below left: Corn Schut inuentor cum priuilegio

Hollstein 103/II.

A previous state without Schut’s name is cited by Nagler.29

Other impression Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.253 (link)

Folio 44

- [97] Saint Martin standing in a landscape, the beggar lying at his feet at right

Etching, 145 × 92 mm. Signed in margin below: Cornelius Schut in cum priuilegio

Hollstein 102.

Other impressions British Museum, 1929,0114.31 (link) and F,1.263 (cropped, link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.254 (link)

For the lost painting, recorded in a painting by David Teniers the Younger of one of the Archduke Leopold William’s exhibition rooms, see Wilmers, op. cit., p. 149 no. A84a, and Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., p.99.

Folio 45

- [98] The Rape of Europa. Jupiter as a bull at centre with Europa on his back, surrounded by her companions, Neptune on his chariot at left, putti holding a garland in top right

Etching, 274 × 368 mm. Signed in margin, right: cum priuilegio

Hollstein 110. Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’, op. cit., 8.3.

On this impression, the inscription in image lower right ‘Cor. Schut Inv. Antver.’ has been masked. The copper matrice is in Antwerp, Stedelijk Prentenkabinet, PK.KP.01571 | KP VIII/11 (link).

Other impressions (both are lettered within image, in lower right: Cor. Schut Inv. Antver.) British Museum, 1983,U.409 (link); Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-59.257 (link)

Comparative illustration

Detail from impression lettered ‘Cor. Schut Inv. Antver.’ in Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, RP-P-OB-59.257 (image source)

Detail from our impression, where the lettering has been masked

Comparative illustration

Detail from copper matrice in Antwerp, Museum Plantin Moretus (PK.KP.01571 | KP VIII/11 (G) (image source)

appendix

Prints contained in the Antwerp album (extract from Museum dataset; link):

- Illustrissimo et excellentissimo D.Andreae Cantelmo

- Titelblad voor “Cantelmus”

- Venus en Cupido in de smidse van Vulcanus

- Ceres in een landschap met saters

- De triomf van Neptunus en Amphitrite

- Borias en Eurythia

- Twee naakte kinderen met vlag en trom

- Fries met 8 bacchanten

- Titelpagina voor ‘Livres d’enfants’

- Zeven spelende kinderen en cherubijn met druiven

- Bacchus, Ceres, Venus, Cupido en twee engeltjes

- De besnijdenis

- Fries met 6 putti en een wereldbol

- Fries met 5 kinderen, Bacchus en 2 cherubijnen

- Drie spelende kinderen met hond en hoepel

- 8 kinderen spelen blindemannetje

- Fries met 9 kinderen en 3 cherubijnen met boog

- 4 spelende kinderen, 1 op een schommel

- Fries met 5 putti, wereldbol, papagaai, luit en Mercuriusstaf

- 4 spelende kinderen, waarvan 1 op een schommel

- Vijf bacchanten

- Twee kinderen voeden een lammetje

- Christuskind met bomen in de wolken

- Madonna met kind in wolken

- Twee naakte kinderen tussen fruitschalen

- Twee zittende naakte kinderen

- Drie naakte kinderen bij een houtvuurtje

- Twee kinderen, waarvan er 1 zit en vruchten plukt

- Christuskind en kleine St. Jan omhelzen elkaar

- Kleine St. Jan knielt voor Christuskind met kruis”,

- Kleine St. Jan, knielend bij een bron, met links het lam

- Kleine St. Jan zittend op een rots bij een bron, rechts het lam

- Christuskind op de wolken, zegenend, met kruis

- Christuskind en de wolken, zegenend, met wereldbol

- Vanitas: kind met zandloper, doodshoofd en zeepbellen

- Vanitas: kind met zandloper en zeepbellen

- De lucht: kind met vruchten rijdt op een ploeg door de lucht

- Kind met kanon

- Het water: vissend kind

- 3 vliegende putti met vlindervleugels

- Putto met palmtak en bloemenkrans

- Twee kinderen bij een kanon

- Het vuur: naakte jongen bij vuur met blaasbalg

- De aarde: jongetje met spade en vruchten

- Vier spelende kinderen, 1 met vaandel en helm

- Drie spelende kinderen, twee worstelend, 1 knielend

- Maria gekroond door Christuskind, aanbeden door heiligen

- Madonna met kind in cartouche vastgebonden door putti

- Madonna en kind met Sint Jan en het lam; Putti in de boom en wolken

- Annunciatie

- Madonna met kind, kleine Sint Jan en lam, en engel met krans

- Aanbidding der herders

- Madonna met kind en kleine St. Jan

- Annunciatie

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna, Jezuskind met druiventros en Sint Janneke met lam

- Madonna, met kind, kleine Sint Jan met lam en 4 putti

- Madonna, Jezuskind, kleine Sint Jan met lam, en rozenstruik

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind, tafel met rozen in vaas

- Heilige familie met vruchtenmand

- Madonna met kind naast pilaar

- Madonna met slapend kind, Sint Janneke met kruis

- Heilige familie met kleine Sint Jan

- Madonna met kind in wolken

- Madonna en kind met appel achter ballustrade

- Madonna en kind met doornkroon

- Madonna en kind achter balustrade

- Madonna met zoon

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind, kleine Sint Jan met bomen en appel

- Jezuskind, lam Gods en kleine Sint Jan

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna en kind

- Madonna met kind

- Triomferende Christus op het graf

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met zogend kind

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind

- Heilige familie met kleine Sint Jan

- Madonna met liggend kind

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind

- God de Vader en de Heilige Geest

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna en kind, vruchten plukkend

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind

- Twee engelen met de dode Christus onderaan het kruis

- Madonna met druiventros en kind

- Madonna en kind met druiventros

- Madonna met kind

- Visitatie

- Christus geknielt aan de geselkolom

- Christus naast de geselkolom

- Christus zittend op de geselkolom

- Christus leunend op de geselkolom

- De kroning van Maria met musicerende engelen

- Christus aan het kruis met Johannes en de drie Maria’s

- Gebonden Christus, geknield, halfgedraaid

- Gebonden Christus, geknield

- Drievuldigheid

- Triomferend Christuskind met wereldbol gedragen door engeltjes

- St. Michiel overwint het kwaad

- Stervende St. Sebastiaan bijgestaand door engelen en Irene

- St. Martinus en de bedelaar

- Triomferend Christuskind met laurier in de wolken, steunend op putti

- Suzanna en de ouderlingen

- Suzanna en de ouderlingen

- Maria gekroond door de drievuldigheid

- Tyramus en thisbe

- Tyramus en thisbe

- Madonna met kind en kleine St. Jan

- Madonna met kind en kleine St. Jan

- Madonna met kind

- Madonna met kind en kleine St. Jan

- Madonna met kind op de maansikkel

- De zeven vrije kunsten

- Astrologia

- Geometria

- Dialectica

- Rhetorica

- Grammatica

- Arithmetica

- Musica

- De marteldood van Johannes

- De bekering van Saul

- Christus aan het kruis met Johannes en Maria

- De marteldood van St. Joris

- Portret van François Eugene van Savoye [not by Cornelis Schut]

- De marteldood van Laurentius

- De verheerlijking van St. Laurentius

1. Perhaps a paper manufactured by Heusler, the leading Basel family of paper manufacturers; compare Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (dfg), Piccard Online (link). Related marks with the suspended initials rp are reproduced by W.A. Churchill, Watermarks in paper, in Holland, England, France, etc., in the xvii and xviii centuries (Amsterdam 1935), no. 286; Erik Hinterding, Rembrandt as an etcher, translated from the Dutch by Michael Hoyle (Ouderkerk aan den IJssel 2006), i, p.45 and ii, p.65, from Rembrandt prints struck c. 1635-1647 (reproduction iii, p.111). The album of Schut prints in the Stedelijk Prentenkabinet, Antwerp, is struck on a paper with the same or similar watermark (see comparable albums below).

2. Compare Raymond Gaudriault, Filigranes et autre caractéristiques des papiers fabriques en France aux xviie et xviiie siècles (Paris 1995), p.258 (a Limousin paper, made by Jean Poyleve); C.M. Briquet, Les Filigranes, second edition (Amsterdam 1968), ii, p.655 no. 13,219 (Bruges papers of earlier date, lettered: I Poylevr).

3. See Antony Griffiths, The print before photography: an introduction to European printmaking, 1550-1820 (London 2016), p.179.

4. See Gertrude Wilmers, Cornelis Schut (1597-1655): a flemish painter of the high Baroque (Turnhout 1996), identifying 113 ‘authentic’ paintings, and 318 works mainly known at second hand.

5. F.W.H. Hollstein, Dutch and Flemish etchings, engravings and woodcuts ca. 1450-1700 [volume] 26: François Schillemans to J. Seuler, compiled by Dieuwke de Hoop Scheffer (Amsterdam 1982), pp.115-160 nos. 1-203 (nos. 204-208 are doubtful attributions).

6. Wilmers, op. cit., p.39. The production of devotional images in Early Modern Europe, particularly in specialist workshops located in Antwerp, their intended audience, and their use, has become an established field of research. See the extensive bibliography in Walter S. Melion, The meditative art: studies in the northern devotional print, 1550-1625 (Philadelphia 2009), pp.395-415.

7. Hollstein, op. cit., no. 25 (our album, print ■ [31]).

8. For an analysis of Schut’s prints by subject, see Ann Diels, The shadow of Rubens: print publishing in 17th-century Antwerp: prints by the history painters Abraham van Diepenbeeck, Cornelis Schut and Erasmus Quellinus ii, translated from the Dutch by Irene Schaudies and Michael Hoyle (London 2009), pp.224, 229. She calculates that ‘only 6% of Schut’s paintings were reproduced as prints’ (p.72).

9. On assistants in Schut’s studio who were also printmakers, see Wilmers, op. cit., p.39; Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., pp.207-222. Perhaps the most original etching in the album is a ‘Christ on the Column’ (our album, print ■ [89]), an experiment with soft-ground etching, then a technique practiced only by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione in Italy; Ann Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre de Rubens’ estampes d’après des peintres d’histoire anversois, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Brussels, 27 November 2009-5 February 2010 (Brussels [2009]), pp.115-116 no. 7.15; and Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., pp.217-218 fig. 23.

10. Wilmers, op. cit., p.232.

11. Erik Duverger, Antwerpse kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw [volume] 8: 1658-1666 (Brussels 1995), pp.377-379, no. 2554: ‘1664, 3 Juni. – Inventaris van de platen, prenten en tekeningen door Cornelis Schut, kunstschilder, in het huis van N.N. [i.e., nomen nescio, anonymous or unnamed] de Licht achtergelaten. De inventaris is door notaris J. van Nos opgemaakt op verzoek van Guilliam Huijmans en tegenwoordigheid van N.N. de Licht en N.N. Boulart’. ‘N.N. de Licht’ might be the amateur painter, Andries de Licht, who in 1664-1665 was exempted from payment of dues in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke (De Liggeren : en adere historische archieven der Antwerpsche Sint Lucasgilde, Antwerp 1864-1876, pp.361, 941; link).

12. Ger Luijten, ‘Het prentwerk van Cornelis Schut’ in Liber memorialis Erik Duverger : bijdragen tot de kunstgeschiedenis van de Nederlanden, edited by Henri Pauwels, André Van den Kerkhove, Leo Wuyts (Wetteren 2006), pp.131-152 (p.141). Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., p.223.

13. Hollstein, op. cit., no. 137 (our album, print ■ [2]).

14. Hollstein, op. cit., no. 149 (our album, print ■ [1]). See Wilmers, op. cit., pp.119-128 nos. A57-A64, for the tapestries; Hollstein, op. cit., nos. 127-134, for a suite of etchings (title and seven prints) made from intermediary drawings.

15. For a list of prints in the Antwerp album, see Appendix below (extract from Museum dataset; link).

16. Luijten, op. cit., p.142.

17. These series had no fixed contents: Schut supplied title-prints (respectively Hollstein, op. cit., nos. 166 and 203), and he – or the buyer – gathered behind whatever separate sheets were available, or of interest. Diels, ‘Sortant de l’ombre’, op. cit., no. 8.5.

18. Christopher Mendez, Catalogue 26: Old Master prints (London 1973), p.37 item 25: ‘Our volume although certainly not complete (it lacks four of the Liberal Arts series) is very extensive and includes 142 plates which are either signed or obviously autograph, six which are by other engravers after [Schut] and two other plates. One of [Schut’s] own plates is partially coloured in grey and white wash’.

19. Hollstein, op. cit., nos. 5, 8, 33, 34, 37, 45, 48, 82, 84.

20. Hollstein, op. cit., nos. 81, 87, 95, 99.

21. Hollstein, op. cit., nos. 90, 166; Luitjen, op. cit., Afb. 2.

22. Hollstein, op. cit., no. 135.

23. Hollstein, op. cit., no. 205; Diels, The shadow of Rubens, op. cit., pp.222-223.

24. Luijten, op. cit., p.131.

25. The album contains the title-plate, the plate addressed to Cantelmo, 142 plates ‘which are either signed or obviously autograph’, and six prints ‘which are by other engravers after [Schut]’ (catalogue entry). One of the latter is by Remoldus Eynhoudts (link).

26. G.K. Nagler, Neues allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon (Munich 1845), xv, p.88: ‘Sein Werk, besteht aus 176 Darstellungen, unter dem Titel: Cornelii Schutt Antv. Picturae ludentis Genius etc. Dann gab er eine Dedication bei: Has picturae ludentis delicias Cornelius Schut Antverpianus manu, mente, munere D. C. Q. gr. fol. Die Bilder erscheinen in verschiedenem Formate. Es kommen oft mehrere kleinere auf einem Blatte vor, besonders Madonnen mit dem Kinde, mit und ohne Johannes. Die Zahl derselben beläuft sich auf 64. Die Blätter sind aber öfters zerschnitten werden, so dass diese Darstellungen auch einzeln sich finden’ (link).

27. G.K. Nagler, Die Monogrammisten und diejenigen bekannten und unbekannten Künstler aller Schulen [volume 2] Cf-Gi (Munich 1860), p.246 no. 660: ‘Nach der Angabe im Winkler’schen Cataloge III. S. 974 besteht das Werk des C. Schut aus 133 Blättern verschiedenen Formats. Die Verfasser, Huber und Stimmel, machen auf ein Titelblatt mit folgender Dedication aufmerksam: Has picturae ludentis delicias Cornelius Schut Antverpianus manu, mente, munere D. C. Q.‚ gr. fol. Dieses Titelblatt haben wir nicht gesehen, wir kennen aber ein anderes. Unten rechts ist die allegorische Figur der Malerei, links jene der Natur. Oben sind drei Genien, welche ein Tuch mit folgendem Titel halten: Cornelii Schvt Antverpiensis picturae lvdentis Genivs svis natvram seqvens lineis exprimens elementis adornans mysteriis in gvstvm artis, et vsvm eorvm omnivm qvi elegantias amant, tractant aestimant. Am Piedestale links steht: Natura, an jenem rechts: Pictvra. H. 9 Z. 8 L. Br. 7 Z. 10 L.’ (link).

28. Nagler, Die Monogrammisten, op. cit., p.248 no. 17: ‘Im späteren Drucke steht in dem 3 Linien breiten Rande der Name des Künstlers’ (link).

29. Nagler, Die Monogrammisten, op. cit., p.253 no. 63: ‘Im ersten Drucke fehlt der Name, im zweiten steht links ausser dem Ovale: Schüt inuentor cum priuilegio’ (link).