The Faerie Queen: The Shepheards Calendar: together with the other works of England’s Arch-Poët, Edm. Spenser: collected into one volume, and carefully corrected

Bound with Tasso (Torquato). Godfrey of Boulogne: or The recouerie of Ierusalem. Done into English heroicall verse, by Edward Fairefax Gent. And now the second time imprinted, and dedicated to His Highnesse: together with the life of the said Godfrey. London: Printed by [Eliot’s Court Press, for] Iohn Bill, 1624.

- Subjects

- Literature, Italian - Translations into English

- Authors/Creators

- Spenser, Edmund, 1552-1599

- Tasso, Torquato, 1544-1595

- Printers/Publishers

- Bill, John, active 1604-1630

- Eliot's Court Press, active 1584-1640

- Harrison, John, the younger, fl. 1579-1617

- Lownes, Humphrey, active 1587-1630

- Lownes, Matthew, active 1591-1625

- Owners

- Isham, Thomas, 3rd Baronet, 1657-1681 (?)

- Isham, Vere, 1633-1704 (?)

- Lely, Peter, Sir, 1618-1680

- Murray, Charles Fairfax, 1849-1919

- Other names

- Fairfax, Edward, 1580?-1635

Spenser (Edmund)

London 1552? – 1599 London

The Faerie Queen: The Shepheards Calendar: together with the other works of England’s Arch-Poët, Edm. Spenser: collected into one volume, and carefully corrected

[London]: printed by H[umphrey]. L[ownes]. for Mathew Lownes. Anno. Dom. 1617

folio (280 mm), (303) ff., in four parts, I: The Faerie Queene, (193) ff., signed π2 (general title, transcribed above; dedication to Queen Elizabeth) A6 (–blank A1, extracted) B–P6 Q4 R–Z6 Aa–Hh6 (blank Hh6 retained) ¶8 (A Letter of the Authors, letter to Raleigh, dedicatory verses; blank ¶8 retained) and paginated (4) 1–363 (3), (16). The title of The Second part of The Faerie Queene is dated 1613; colophon of second part dated ‘16012’. II: Prosopopoia, (8) ff., signed A8 and paginated 1–16. Title dated 1612. III: Colin Clouts come home againe, Prothalamion, Amoretti and epithalamion, Epithalamion, Foure hymnes, Daphnaida, Complaints, The teares of the Muses, Muiopotmos, (68) ff., signed A–L6 M2 and paginated (26), (4), (16), (6), (16), (10), (12), (28), (18). The title of Colin Clouts come home againe is undated; the eight sub-titles are each dated 1617. IV: Shepheards calender, (34) ff., signed A–E6 F4 (blank F4) and paginated (10), 1–56 (2). Title dated 1617.

Woodcut compartment on general title-page (R.B. McKerrow and F.S. Ferguson, Title-page Borders used in England and Scotland 1485–1640, London 1932, no. 212, originally cut for the 1593 edition of Sidney’s Arcadia); woodcut head- and tail-pieces, ornaments, series of 12 woodcuts of the seasonal occupations in Shepheards calender (these printed from the same set of blocks used for the preceding quarto editions; see Ruth Samson Luborsky and Elizabeth Morley Ingram, A Guide to English Illustrated Books 1536–1603, Tempe 1998, I, pp.673–681).

Bound with

Tasso (Torquato)

Sorrento 1544 – 1595 Rome

Godfrey of Boulogne: or The recouerie of Ierusalem. Done into English heroicall verse, by Edward Fairefax Gent. And now the second time imprinted, and dedicated to His Highnesse: together with the life of the said Godfrey

London: Printed by [Eliot’s Court Press, for] Iohn Bill, printer to the Kings most Excellent Maiesty, 1624

folio (280 mm), (208) ff., signed ¶4 )(4 A4 B–Z6 Aa–Kk6 Ll4 and paginated (24) 1–392. Title within ornamental woodcut border (McKerrow and Ferguson, op. cit., no. 283). lacking (as often) frontispiece/portrait of Godfrey, by Willem van de Passe (1598–c. 1637).1

provenance (before rebinding) Spenser: early ownership inscription on title-page (cropped by binder’s knife when rebound); occasional marginal annotations (some likewise cropped). Tasso: presentation inscription on title-page: LB’s gift to P Lely 1656 [i.e., John Baptist Gaspars (1620–1691), known as ‘Lely’s Baptist’?] — Peter Lely (1618–1680), inscriptions and monograms on title-pages and endpapers (see below) — [Thomas Isham, 3rd Baronet (1657–1681)?] — inscriptions and pen trials of members of the Isham family, including Vere Isham [Vere Leigh (1633–1704), second wife of the 2nd Baronet, Sir Justinian Isham (1610–1675); or else her granddaughter (1686–1760)] — by family descent, Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, to Sir Vere Isham, 11th Baronet (1862–1941), by whom consigned to — Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable old English books and manuscripts, selected from the library of a gentleman in the country, 17–18 June 1904, lot 3112 — sold to Ellis (James Joseph Holdsworth and George Smith, trading as Ellis, 29 New Bond Street, London), £10 10s3 — Charles Fairfax Murray (1849–1919) — Sotheby, Catalogue of a further portion of the valuable library collected by the late Charles Fairfax Murray, 17–20 July 1922, lot 9804 — to Parsons (Edwin Parsons & Sons, 45 Brompton Road, London), £15 — Maggs Bros., [Catalogue] No. 446 English literature: Manuscripts and Printed Books, 14th to the 18th centuries (London 1924), p.511, item 2087, £10 10s6 — Henry Sotheran Ltd, London7

condition Spenser: wormtrack in inner margin of Shepheards calender, touching a few letters; clean paper tear in folio B2. Tasso: lacking frontispiece/portrait; title-page backed; last page dust-soiled. Joints repaired; abrasions and marks to the binding.

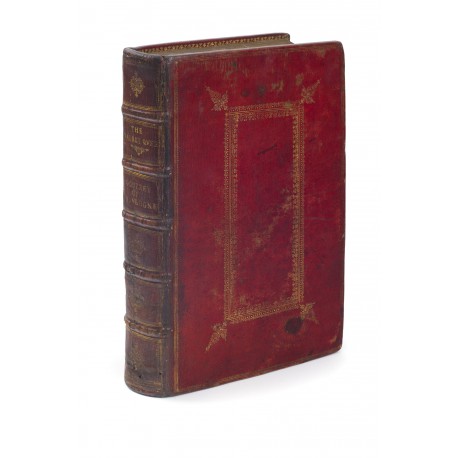

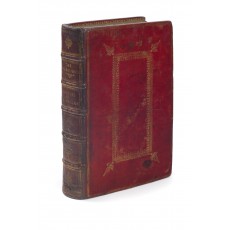

binding London binding circa 1660 of red turkey leather, panel created by a two-line fillet between two sun rolls, floriated ornaments at outer corners, gilt border roll. Back divided into six compartments by raised bands, of which two are lettered directly (The Faerie Queen; Godfrey of Bovlogne) and others decorated by repetition of floriated tools. Gilt sun roll on edges of boards and turn ins. Gilt edges. Comb-marbled pastedowns.

Sir Peter Lely’s copy inscribed with no less than seven different versions of his monogram, and with a rapid landscape sketch on first flyleaf. One of eight known books from Lely’s formal library, it was for more than 200 years subsumed in the famous Isham Library at Lamport Hall, then became the property (briefly) of Charles Fairfax Murray, before passing in 1924 through the hands of Maggs Bros. into private collections, from which it has just emerged.

Unlike most early modern artists, who kept a haphazard accumulation of volumes in their studios, Lely had a ‘Library’, a room in his house on the Piazza in Covent Garden designated for books and for their study. Unfortunately, no inventory survives of this library, and it would seem that the great majority of Lely’s books have been lost, or else have yet to be recognised. Lely’s appointment as Charles II’s Principal Painter in Ordinary and lucrative practice as a portrait painter gave him ample means to collect a library and to assemble also impressive collections of old master paintings, drawings and prints, of all the major European schools, from the late 15th century up to his own time. Lely’s superb collection of old master prints, the first significant collection formed in Britain,8 was an integral part of an extensive repertoire of models useful to Lely in his own practice, to his numerous studio assistants, and perhaps also to students in his ‘academy’. The prints, including some heavily-illustrated books, were thus kept in Lely’s studio, or in an anteroom nearby; accommodated in the formal library were books of a more general nature, though some still were directly relevant to the discipline of the artist.

When Lely died, on 30 November 1680, of an apoplectic fit (said to have been suffered while painting the Duchess of Somerset), his Executors inventoried and valued the paintings in his studio, and slowly began to clear the house of furniture, china, plate, jewellery, and other chattels. The studio contents – Lely’s own paintings, many unfinished, together with pigments, supports, frames, and related materials – were sold at fixed prices, and in April 1682 Lely’s important collection of old master paintings was sold by public auction. Over the following months, the Executors continued to empty the house, in anticipation of letting it to a former studio assistant. The drawing and print collections were removed during the summer for safekeeping elsewhere, and in September 1682 the library was crated up and sent to Lely’s country house in Kew, for the future benefit of his son John, then a pupil of Eton College.9

In March 1686, the lease of Lely’s house was taken over by one of his Executors, Roger North. The drawing and print collections were returned, and North set about organising them for sale. He had metal inkstamps made and with these began to mark the recto of each drawing and print, ‘near 10,000’ separate items, according to North’s computation.10 In April 1688 commenced an auction sale of the drawings and prints, the latter offered in ‘portfolios’ together with some ‘Books of prints bound’.11 Although records of prices and buyers were kept by the auctioneer, and North states that he himself ‘made lists of each book, and described every print and drawing’, no list has survived.12 When, after eight days, ‘the buyers began to be clogged with the quantity, and could not well digest any more’, North interrupted the sale.13 North intended to sell all remaining drawings and prints in April 1689, however ‘this wonderful Revolution came on and hindered me’.14 They eventually were offered in auction sales conducted by Parry Walton on behalf of John Lely in February and November 1694.

The individual prints and ‘Books of prints bound’ sold in 1688 and 1694 can be recognized by the P.L handstamp posthumously applied by Roger North. The books in Lely’s formal library, sent to Kew in 1682, are not thus marked, and their identification depends entirely on inscriptional evidence placed in the volume by Lely or by a subsequent owner. Eight such volumes can be traced (see Checklist A). Of the ‘Books of prints bound’ kept with Lely’s print collection, just two can be identified with certainty;15 another three are indeterminate, as they have since been rebound by later owners (see Checklist B).16 A salient feature of the latter five volumes is that the prints are – unusually – bound on their own paper. In the fashion of the time, Lely normally trimmed his prints close to platemarks or borderlines, and mounted them to album sheets, which were organised in portfolios by artist, subject-matter, or printmaker. Later collectors gathered these mounted prints, sometimes mixing Lely’s impressions with prints they had obtained elsewhere, and placed them in their own bindings.17 Such concocted volumes are excluded from discussion here.

Lely’s marks of ownership

Of the eight known volumes from Lely’s formal library, the present volume, his copy of Spenser’s works (London 1617) bound with Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (London 1624), contains by far the greatest inscriptional evidence. The copies of Spenser and Tasso were acquired by Lely separately and bound-up together at a later date, perhaps in the late 1650s. On the title-page of the Spenser is an ownership inscription left by a previous owner; when the book was rebound, it was cropped by the binder’s knife, and became illegible. Lely effaced what remained, and added his own monogram (PE L). Some of the previous owner’s marginal annotations have also been cropped.

The title-page of the Tasso is inscribed LB’s gift to PLely 1656; the hand might be Lely’s, recording the gift, or the donor’s. Elsewhere in the volume, a pen and ink ornament is flanked by the monograms P Lely and LB. The identity of ‘L.B.’ (or B.L.) is unknown, unless he should be the painter-etcher Jan (John) Baptist Gaspars (1620–1691), a former pupil in Antwerp of Anthony van Dyck and Thomas Willeboirts, who worked as a drapery painter for Lely, and became known as ‘Lely’s Baptist’.18 In 1656, Lely was travelling in Holland with the architect Hugh May, a sometime lodger in his house in Covent Garden, who in 1680 was to become one of the three Executors of his estate.19

The identity of ‘LB’ is unknown, unless he should be John Baptist Gaspars, known as ‘Lely’s Baptist’

The binder has lined the inside covers with a comb-marbled paper and inserted two conjugate plain endleaves at the front of the volume, and another two at the back. These binders’ leaves have been inscribed by Lely with monograms, either his initials in ligature (PL, Pe L) or name (P. Lely). Comparable monograms are seen on Lely’s drawings. Another monogram combines the letters CMAVL (?) and may signify Lely’s sister, Catharina (or Anna Catharina) Maria (1638–1710), wife of Coenraedt Wecke, burgemeester of Groenlo, near Zutphen, whom Peter likely visited in Holland in 1656.20

bound with Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (London 1624

On the front paste-down, the number 2326 is inscribed in reddish-brown ink between two horizontal lines. A similar inscription, the number 130, occurs on the front free-endpaper of Lely’s copy of Antonio Tempesta, Metamorphoseon sive Transformationum Ovidianarum libri quindecim (Antwerp 1606), one of the ‘Books of prints bound’ kept within Lely’s print collection. If we can assume that these two volumes parted company at an early date – Lely’s Spenser / Tasso to Kew with the formal library in 1682, if not removed before; Lely’s Tempesta / Ovid, inkstamped by Roger North in 1686, and sold with the print collection in 1688 or 1694 – then these inscriptions could be by Lely himself.

Below Comparative illustration 130, in Lely’s Tempesta / Ovid

The degree to which these books may have played a role in Lely’s artistic production is unclear. Recent discussions of Lely’s subject paintings produced in the 1640s and 1650s have identified his chief literary influences as the Bible, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Boccaccio’s The Decameron. Lely’s depictions of idyllic, wooded landscape charged with poetic and symbolic content are linked to his possession of editions of Spenser and Tasso, and presumed knowledge of Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, although there is no evidence that ‘influence’ has indeed occurred.24

Isham Library

Sir Justinian Isham (1610–1675), or else her granddaughter (1686–1760)

In addition to inscriptions placed in the volume by Lely himself, an inscription and pen trials were entered by members of the Isham family of Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire. During the 1670s, Lely painted two portraits of the 3rd Baronet, Thomas Isham (1657–1681): one was finished some months before the sitter’s departure to Italy, in October 1676, for presentation to Roger Spencer, Lord Teviot; the other was painted after 1679 (both portraits are now at Lamport).25 It may be that this book became alienated from Lely’s library when Thomas Isham sat for his portrait. The signature ‘Vere Isham’ could be that of Thomas’s mother, Vere Leigh (1633–1704), second wife of the 2nd Baronet, Sir Justinian Isham (1610–1675),26 or else that of her granddaughter (1686–1760).

The library, founded by Thomas Isham (1555–1605), who purchased works of English poetry, including the 1599 editions of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis and The Passionate Pilgrim,27 was enhanced by his son, John, the first baronet (1582–1651), who added the first edition of Don Quixote and about forty Italian books. The latter’s son, Justinian, the second baronet (1610–1675), a fellow-student of Milton’s at Christ’s College, Cambridge, added first editions of Paradise lost and Paradise regained, and books given to him by Ben Jonson, Sir Thomas Browne, Jeremy Taylor, Izzak Walton, and Henry Vaughan. The third baronet, Thomas, who sat for Lely aged nineteen, and had his armorial bookplate engraved by David Loggan in 1676, bought on a protracted Grand Tour large numbers of Italian books and prints;28 this promising bibliophile died of smallpox in July 1681, aged only 20. The Isham Library was brought to general notice in 1867, when Charles Edmonds of the London booksellers Willis & Sotheran made the sensational discovery of the precious Elizabethan books in a storeroom. Edmonds prepared a manuscript catalogue of the Lamport library and in 1880 published an impressionistic précis, in which Lely’s Spenser / Tasso is cited.29 Most subsequent accounts of the Lamport Hall library also cite Lely’s Spenser / Tasso, notably those published by H.A.N. Hallam (in The Book Collector)30 and by Douglas Gordon.31

The many extraordinary rarities of Elizabethan poetry and prose, about 130 titles, were sold in 1893 to Wakefield Christie-Miller of Britwell Court and to the British Museum; a further portion of the library, about 350 volumes, including this volume, was sent to Sotheby’s in 1904. The pencil inscriptions ‘page 222 | H6’ on second front endpaper (verso) locate the book in Edmonds’ manuscript catalogue of the Isham Library and place in the library. Other pencil annotations on the endpapers document its subsequent passage through the trade: ‘Sir Peter Lely’s copy, with his autograph signature several times repeated | The “Godfrey of Boulogne” lacks the portrait | a few wormholes in inner blank margin’ (corresponds to Maggs Bros. printed catalogue entry; on first front endpaper, recto); ‘1990’ | ‘Sir Peter Lely’s copy, with his autograph’ (on first front endpaper, verso); ‘18017’ | ‘Cat.’ | C ] | ÷ (bookseller’s price code; on second back endpaper, recto).

Binding

After Lely’s death his Executors proceeded to settle his debts, among which was one to the bookbinder William Nott (fl. 1660–1691) for the considerable sum of 13 guineas.32 William Nott, mentioned in Pepys’s diary in 1669 as ‘the famous bookbinder that bound for my Lord Chancellor [Clarendon]’s library’,33 was proprietor of a large workshop in Pall Mall, whose clientele during the 1670s included both Catherine of Braganza and Mary of Modena. Nott employed numerous finishers, of varying abilities, working in different styles, who had access to a wide variety of tools. Unfortunately, none of the shop’s most distinctive tools – drawer-handles, four-petalled rosettes, volutes with pointillé outlines – were used on Lely’s Spenser / Tasso, nor on other books from Lely’s library known to the writer. The tools employed on the covers and spine of Lely’s Spenser / Tasso are generic and defy assignment to a specific bindery. Some features – a gilt sun-roll on the edges of the boards and turn-ins, comb-marbled endleaves, and pink, white, and blue headbands – are characteristic of bindings associated with Nott’s shop,34 but it would be unwise to attribute this binding to Nott’s shop on such slender evidence.

The binder has employed for the endleaves a paper from the Durand mill in Normandy: in seventeenth-century England, the name Durand ‘was a symbol of excellent “Paper out of France”’.35 The large watermark (height 98 mm), featuring the arms of France and Navarre, a Maltese cross beneath, and subscript ‘A Durand’, is similar (but not identical) to marks recorded in use in 1651 and c. 1673–1680.36

Spenser

The printing history of Spenser’s collected Works is unconventional. The brothers Humphrey and Matthew Lownes printed all the parts, from 1611 to sometime after 1620, except the 1617 printing of The Shepheardes Calender (printed by John Harrison II). Because of the independence of the sections (each has its own title-page), and the absence of sequential pagination, buyers could purchase an individual part or parts, or the entire folio, and arrange the contents as they saw fit.37 This flexibility also suited the publishers, as it limited their financial risk: if the Works did not sell well, sales of separate parts might recoup the investment. Parts could be reprinted according to demand, often years apart from the date on the general title-page.

Francis Johnson defined four groups under which copies of the Spenser folio containing all seven parts may be classified.38 The present copy belongs in his Group IV, with the parts bound in this order: (1) General title-page and dedication to Queen Elizabeth: corresponds to Johnson 19B (second printing, 1617); (2) Faerie Queene, first part: corresponds to Johnson 19B (second printing, c. 1613–1617); (3) Faerie Queene, second part: corresponds to Johnson 19B (second printing, c. 1612–1613); (4) Letter to Raleigh: corresponds to Johnson 19B (second printing, [1617]); (5) Prosopopoia or Mother Hubberds Tale: corresponds to Johnson 19A (first printing, 1612–1613); (6) Colin Clouts come home againe and minor poems: corresponds to Johnson 19B (second printing, 1617); (7) Shepheards Calender: corresponds to Johnson 19B (second printing, 1617).

Tasso

A reprint of the first edition (1600) of Edward Fairfax’s translation in octaves of Gerusalemme liberata, with a new dedication by John Bill, the King’s printer, to Charles, Prince of Wales, who had highly commended the poem.39 Other matter not in the first edition are a poem to him and a Life of Godfrey; everything else in the edition is merely reprinted and has no independent textual authority.40 This work and Spenser’s Faerie Queene are supposed to have been a solace to Charles I during his imprisonment in Carisbrooke Castle (ODNB).

references Spenser: STC 23085; the ESTC lists the ‘other works’ separately. Tasso: STC 23699

Checklist A — Books from Peter Lely’s Library

A / 1

Ariosto (Lodovico), Orlando furioso in English heroical verse. By Sr Iohn Harington of Bathe Knight (London: Imprinted by G. Miller for I. Parker, 1634)

subsequent provenance

● Victor Albert George Child Villiers, 7th Earl of Jersey (1845–1915)

● Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Osterley Park library: catalogue of this important collection of books, the property of the Rt. Hon. the Earl of Jersey, 6–14 May 1885, p.7, lot 83 (‘fine copy, with autograph of Sir P. Lely, in old English red morocco, gilt edges’; link) – to Pickering, £12 15s

● Robert Hoe (1839–1909); James O. Wright and Carolyn Shipman, Catalogue of books by English authors who lived before the year 1700, forming a part of the library of R. Hoe (New York 1903–1905), II, p.320 (‘contemporary red morocco, gilt back and side panels, gilt edges… The autograph of Sir Peter Lely is on the first title’; link)

● Anderson Auction Company, Catalogue of the library of Robert Hoe of New York; illuminated manuscripts, incunabula, historical bindings, early English literature, rare Americana, French illustrated books, eighteenth century English authors, autographs, manuscripts, etc., part III, 15–19, 22–26 April 1912, p.191, lot 1427 (‘contemporary red morocco, gilt edges… The autograph of Sir Peter Lely is on the first title’; link) – Sold for $10 (American Book Prices Current, 1912, p.31; link)

● San Marino, Huntington Library, 99001 (‘signatures of [Sir] P[eter] Lely, and Robert Hoe 1885’; OPAC)

A / 2

Boccaccio (Giovanni), Il Decameron di Messer Giovanni Boccacci, cittadino Fiorentino. Si come le diedero alle stampe gli SSri Giunti l’anno 1527 (Amsterdam: [Daniel Elzevier], 1665)

subsequent provenance

● Pickering & Chatto, Catalogue of old and rare books (London 1895), p.145, item 1362 (‘Contemporary red morocco extra, gilt edges, with the autograph of Sir Peter Lely, the celebrated portrait painter, on title, £4 4s’; link)

● Pickering & Chatto, Catalogue of old and rare books; and a collection of valuable old bindings (London 1900), p.112, item 1037 (‘contemporary red morocco extra, gilt edges, with the autograph of Sir Peter Lely, the celebrated portrait painter, on title, £4 4s’; link)

● J. Pearson & Co., One hundred books from the cabinets of royal and distinguished bibliophiles from Grolier to Beckford (London 1901), p.34, item 35 (‘Contemporary red morocco, gilt edges. Sir Peter Lely’s copy, with his signature on the title-page. Examples from the library of this great painter are very rare. 25 guineas’; link)

● [Anonymous consignor to] Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable & rare books and illuminated and other manuscripts, 11–15 December 1903, lot 714 (‘old morocco extra… Sir Peter Lely’s copy; his autograph is on the title-page. Examples of his library are rare’) – Sold to Buck, £1 5s [bought-in?] (Book Prices Current, volume 18, 1904, p.124, entry 1472)

● J. Pearson & Co., A unique and extremely important collection of autograph letters of the world’s greatest painters of the XVth, XVIth, XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries (London c. 1911), p.12, item 29 (‘His signature, affixed to the title page of the Elzevir edition of “Il Decameron,” 1665. £8 8s’; link)

citation

● [W.C. Hazlitt], ‘English and Scottish book collectors and collections – Part II’ in The Bookworm; an illustrated treasury of old-time literature 7 (1894), p.102 (‘With his autograph on title’; link)

A / 3

Drayton (Michael), Poly-Olbion or A chorographicall description of tracts, riuers, mountaines, forests, and other parts of this renowned isle of Great Britaine (London: Printed by H[umphrey] L[ownes] for Mathew Lownes: I. Browne: I. Helme, and I. Busbie, 1613)

subsequent provenance

● [possibly William Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Devonshire (1673–1729), a buyer in second sale of the Lely collection, also in the Prosper Henry Lankrink sales in 1693–1696; by descent]

● Chatsworth, Dukes of Devonshire

citation

● James Phillip Lacaita, Catalogue of the library at Chatsworth (London 1879), II, pp.57–58 (‘Sir P. Lely’s copy, with his autograph on the title-page’; link)

A / 4

Fréart de Chambray (Roland), An idea of the perfection of painting : demonstrated from the principles of art, and by examples conformable to the observations, which Pliny and Quintilian have made upon the most celebrated pieces of the ancient painters, parallel’d with some works of the most famous modern painters, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Julio Romano, and N. Poussin (London: In the Savoy: printed for Henry Herringman at the sign of the Anchor in the lower-walk of the New-Exchange, 1668)

provenance

● Presentation inscription by the translator, John Evelyn (1620–1706), to Peter Lely

● Pickering & Chatto, The Book Lovers’ Leaflet no. 245: A Collection of old and rare books of (with some exceptions) English literature. Addenda (Cum-Hey) (London c. 1926–1928), p.1873, item 12356a (‘original calf, Presentation copy from Evelyn to Sir Peter Lely, with autograph inscription, ‘For my honor’d friend | Mr Lely from his | humble servt. | J. Evelyn.’ … and with seven corrections in text in Evelyn’s hand, including the filling in of one word in preface, in all copies left blank: Fine copy. £95’; link)

● Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, *EC65.Ev226.668f (‘Inscribed on front flyleaf: For my honor’d Friend Mr. Lilly [i.e. Sir Peter Lely], from his humble Sert.: Evelyn’; bound in ‘Full contemporary calf’; OPAC)

A / 5

Lomazzo (Giovanni Paolo), A Tracte containing the artes of curious paintinge carvinge & buildinge (Oxford: By Ioseph Barnes For R.H. [Richard Haydocke], 1598)

subsequent provenance

● Unknown purchaser from Peter (or John) Lely, inscription on endleaf ‘20 Sc[h]il[lings] of Mr Lely’

● Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke (1690–1764), armorial bookplate (Philip Lord Hardwicke | Baron of Hardwicke | in ye County of Gloucester, [motto] nec cupias nec metuas)

● by family descent, Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire, until 1894, when the estate sold to Thomas Agar-Robartes, 6th Viscount Clifden (1844–1930)

● by descent, until consigned by Francis Agar-Robartes, 7th Viscount Clifden (1883–1966), to

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, comprising a selected portion of the library at Wimpole hall, Royston, the property of the Rt. Honble. Viscount Clifden, 22–23 July 1937, lot 115 (‘engraved title, slightly defective and laid down, engravings, wants leaf bearing imprint, stained and cut into, old red morocco gilt, panelled sides, g.e., sold not subject to return’) – Sold to ‘Edwards, £5’ (Book Auction Records, volume 34, 1937, p.595)

● Christie’s, ‘Printed books; the property of a charitable trust, the trustees of the Stoneleigh Settlement, the executors of the late 4th Lord Leigh, Stoneleigh Abbey Preservation Trust Ltd and from various sources’, 18 November 1981, lot 191, lot 260 (‘seventeenth century English red morocco, side panelled in gilt, spine gilt, bookplate of Lord Hardwicke… A note in a late seventeenth century hand reads: ‘20 Scill of Mr Lely’. The name is uncommon in England and this very likely refers to Sir Peter Lely.’) – Sold to Alan Thomas, £1200 (Book Auction Records, volume 79, 1982 p.342)

● Dr Howard Knohl, Foxe Ponte Library, Anaheim Hills, CA, consigned to

● Sotheby’s, Selections from the Fox Pointe Manor Library, New York, 26 October 2016, lot 191

● Chicago, T. Kimball Brooker collection

A / 6

Olearius (Adam), The voyages and travells of the ambassadors sent by Frederick, Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy and the King of Persia : begun in the year M. DC. XXXIII. and finish’d in M. DC. XXXIX : containing a compleat history of Muscovy, Tartary, Persia, and other adjacent countries (London: printed for John Starkey, and Thomas Basset, at the Mitre near Temple-Barr, and at the George near St. Dunstans Church in Fleet-street, 1669)

subsequent provenance

● Frederick Clarke (1830–1903), Ormond House, Wimbledon

● Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the valuable library of the late Frederick Clarke (of Ormond House, Wimbledon), 31 October 1904, p.62, lot 851 (‘old morocco extra, g.e.’) – Sold to Elliston, £1 10s (Book Auction Records, volume 2, 1905, p.107)

● Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of fine books, illuminated & other manuscripts, and valuable bindings, 17–18 October 1918, lot 219 (‘old morocco gilt, gilt edges, autograph of Sir Peter Lely on title, w.a.f’) – Sold to Ellis £5 10s (Book Auction Records, volume 16, 1919, p.58; link)

citations

● Frederick Clarke, ‘Sir Peter Lely, 1617–1680’ in Contributions towards a Dictionary of English Book-Collectors as also of some Foreign Collectors whose libraries were incorporated in English collections or whose books are chiefly met with in England, edited by Bernard Alexander Christian Quaritch (London 1892–1921; reprinted London 1969), part IV (April 1893), p.183 (‘bears the painter’s well-known autograph on the title-page… none of [Lely’s] biographers mention his books’)

● [W.C. Hazlitt], ‘English and Scottish book collectors and collections – Part II’ in The Bookworm; an illustrated treasury of old-time literature, volume 7, 1894, p.102 (‘With Lely’s autograph’; link)

A / 7

Randolph (Thomas), Poems with the Muses looking-glasse. Amyntas. Jealous lovers. Arystippus. The fourth edition inlarged (London: [s.n.], Printed in the yeere 1652)

subsequent provenance

● Philadelphia Dyke, daughter of Sir Thomas Nutt, of Selmeston, Sussex, and Philadelphia Nutt; married 1677 Thomas Dyke, 1st Baronet (c. 1650–1706), of Horeham, Sussex

● Thomas Thorpe, A General Catalogue of an interesting and valuable collection of rare, curious, and useful books in all languages and branches of literature, Part III (London 1830), p.148, item 11340 (‘old morocco, gilt leaves, 15s. This copy was the gift of Sir Peter Lely, Knt., the famous painter, to Philadelphia Dyke’; link)

● Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, *EC R1598 638pd (‘Inscribed: Ex donati Petri Lillai equitis aurati pictoris celeberrimi P. Dyke [&] The Gift of Sr Peter Lilly Kt. the most famous painter of the age, to Philadelphia Dyke’; ‘Contemporary maroon calf, gilt’; OPAC)

A / 8

Spenser (Edmund), The faerie queen: The shepheards calendar: together with the other works of England’s arch-poët, Edm. Spenser: collected into one volume, and carefully corrected ([London]: printed by H[umphrey]. L[ownes]. for Mathew Lownes, 1617) — Bound with: Tasso (Torquato), Godfrey of Boulogne: or The recouerie of Ierusalem. Done into English heroicall verse, by Edward Fairefax Gent. (London: Printed by [Eliot’s Court Press, for] Iohn Bill, 1624)

provenance

● Spenser: illegible ownership inscription on title-page (cropped by binder’s knife when rebound), marginal annotations, some likewise cropped

● [possibly John Baptist Gaspars (1620–1691), known as ‘Lely’s Baptist’], inscription (on title-page of Tasso): LB’s gift to P Lely 1656

● Peter Lely (1618–1680), inscriptions and monograms on title-pages and endpapers

● [possibly Thomas Isham, 3rd Baronet (1657–1681)], inscriptions and pen trials, including ‘Vere Isham’ [probably Vere Leigh (1633–1704), second wife of the 2nd Baronet, Sir Justinian Isham (1610–1675); or else her granddaughter (1686–1760)], by family descent, Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, to

● Sir Vere Isham, 11th Baronet (1862–1941), by whom consigned to

● Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable old English books and manuscripts, selected from the library of a gentleman in the country, 17–18 June 1904, lot 311 (‘old English morocco gilt, gilt edges… This volume was formerly Sir Peter Lely’s. It has his autograph twice on the fly-leaf of the Spenser, with some sketches; and also on the title of the Tasso’) – Sold to Ellis (J.J. Holdsworth and George Smith), 29 New Bond Street, London, £10 10s (Book Prices Current, volume 18, 1904, p.578, item 5809; link)

● Charles Fairfax Murray (1849–1919)

● Sotheby, Catalogue of a further portion of the valuable library collected by the late Charles Fairfax Murray, 17–20 July 1922, p.104, lot 980 (‘inscription “P. Lely” on fly-leaf in a 17th century hand… inscription on title [of Tasso] “B.L.’s (or L.B.’s) gift to P. Lely, 1656,” title backed, wants portrait… in 1 vol., old morocco, gilt, g.e., sold not subject to return’) – to Parsons, £1 (Book Auction Records, volume 19, 1922, p.716)

● Maggs Bros., [Catalogue no. 446] English literature: manuscripts and printed books, 14th to the 18th centuries selected from the stock of Maggs Bros.; with sixty-one illustrations (London 1924), p.511 no. 2087 (‘17th century English red morocco, g.e. … From the Library of the celebrated English Painter, Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680), with his Autograph Signature several times repeated’; link)

● Henry Sotheran Ltd, London, offered at ABA Olympia book fair, 26–28 May 2016 (link)

citations

● Charles Edmonds, An annotated catalogue of the library at Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, the seat of Sir Charles E. Isham, Bart. including copious notes and observations on the rare, unique, and hitherto-unknown books of English poetry, early English plays, and prose works, as well as on other interesting books and manuscripts preserved therein ([England: publisher not identified], 1880), p.5 (‘Various autograph signatures… Sir Peter Lely (who painted the Portrait of Sir Thomas Isham), with a pen sketch by him, and the Initials of Miss Vere Isham, in Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Jerusalem. Page 222 [in Edmonds’ manuscript catalogue of the library, now lost)

● Douglas Gordon, ‘The Book-Collecting Ishams of Northamptonshire and Their Bookish Virginia Cousins’ in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 77 (1969), pp.174–179 (p.176, appearance in 1904 sale cited)

● H.A.N. Hallam, ‘Unfamiliar libraries XII: Lamport Hall revisited’ in The Book Collector 16 (1967), pp.439–449 (p.448: ‘There was, for instance, a volume of Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata 1621, bound with Spenser’s Faerie Queen 1617. This contained the signature of Sir Peter Lely, who painted the portrait of Sir Thomas Isham, of which there are two versions in the house, with a pen sketch by him. This volume, which realized two guineas only, has disappeared from view after its sale in 1921 to a dealer who has since died’.)

● Oliver Millar, Sir Peter Lely 1618–80 [catalogue of the] e xhibition at 15 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1 [from 17 November 1978–18 March 1979] (London 1978), p.12 (cited)

● David A.H.B. Taylor, ‘Lely in Arcadia: Religious, pastoral, musical and mythological themes in Peter Lely’s subject pictures’ in Peter Lely: a lyrical vision, edited by Caroline Campbell, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Courtauld Gallery, London, 11 October 2012–13 January 2013 (London [2012]), p.67

Checklist B — Bound suites of prints from Peter Lely’s Print collection

B / 1

Bisschop (Jan de), Signorum veterum icones. – Bound with: Paradigmata graphices variorum artificum ([s.l.; Amsterdam or The Hague?], c. 1668–1671)

provenance

● Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092–2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

● [presumably auction sale of prints and drawings belonging to Lely, at his house in the Great Piazza, Covent Garden, 16 April 1688]

● Prosper Henry Lankrink (1628–1692) (Lugt 2090; link), who spent £242 17s in Lely’s 1688 auction

● [presumably auction sale of the library of Prosper Henry Lankrink at his house in Covent Garden, 29 May 1693 (link); or auction sales of Lankrink’s prints and drawings, 8 May 1693 (link), 22 February 1694 (link)]

● Algernon Capell, 2nd Earl of Essex (1670–1710), by descent to

● George Capel-Coningsby, 5th Earl of Essex (1757–1839), by whom given in 1827 to his son-in-law

● Richard Ford (1796–1858), by descent to

● Brinsley Ford (1908–1999), by descent to

● Augustine Ford (b. 1943), London

citation

● Brinsley Ford, Charles Avery and John Mallet, ‘Richard Ford (1796–1858)’ in The Volume of the Walpole Society 60 (1998), p.26 (‘Two of the most beautiful books in the library were given by Lord Essex to Richard Ford in 1827 – the two volumes of etchings by Ian Bisschop published in The Hague in 1671… These volumes belonged to Sir Peter Lely, since each plate bears his collector’s mark. On Lely’s death the volume passed to P.H. Lankrink who also added his collector’s mark to all the plates…’)

● Diana Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’ in Collecting prints and drawings in Europe, c. 1500–1750, edited by Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam, and Genevieve Warwick (Aldershot 2003), pp.137–138 (‘every individual page has the PL stamp, North’s numbering system appears just once on the title-pages’)

B / 2

Moerman (Joannes), Apologi creaturarum ([Antwerp]: [Christopher Plantin for Gerard de Jode], 1584)

provenance

● Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon (c. 1594/1597–1652), for whom bound in 1637

● Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092–2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

● Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of… the Beckford Library, removed from Hamilton Palace, London, 30 June–11 July 1882, lot 2521 (‘fine impressions, each plate stamped P.L. on margin, old black morocco’) – sold to Quaritch, £9 10s

● Bernard Quaritch, General Catalog of Books Offered to the Public at the Affixed Prices (London 1883) p.1390 no. 13788 (link)

● Alfred Denison (1816–1887), Ossington Hall, Nottinghamshire, by descent to his nephew, William Evelyn Denison (1843–1916), consigned by the latter’s widow, Lady Elinor Denison (1850–1939), to

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the celebrated collection of books relating to angling and of a small general library formed by the late Alfred Denison, London, 17 July 1933, lot 158 – sold to Sexton, £4 15s (Book Auction Records, volume 30, 1933, p.469)

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, illuminated & other manuscripts, autograph letters & historical documents, London, 18 December 1933, lot 79, offered among ‘Other properties’, ‘black morocco, Hamilton Palace (Beckford collection) and Arthur [sic] Denison bookplates’ – sold to Sherwood, 12s (Book Price Current, volume 48, 1934, p.503)

● J.H. Gispen, Nijmegen

● J.L. Beijers, ‘The fine library of the late J.H. Gispen, Esq.’, Utrecht, 29 May 1973, lot 185 (‘From the Hamilton Palace Library’)

● Amsterdam, University Library

citations

● H. de la Fontaine Verwey, ‘Het mysterie van de zwarte banden met het jaartal 1637’ in Bibliotheekinformatie: Mededelingenblad voor de Wetenschappelijke Bibliotheken 11 (1973), pp.11–14 (speculating wrongly that the binding was commissioned by Hendrick Van den Borcht, who in 1637 was appointed curator of the Earl of Arundel’s collections)

● Jan Gerrit van Gelder and Ingrid Jost, Jan de Bisschop and His Icones & Paradigmata: Classical Antiquities and Italian Drawings for Artistic Instruction in Seventeenth Century Holland (Doornspijk 1985), p.203 note 30: ‘once owned by Sir Peter Lely whose collector’s mark (L. 2092) is to be found on all sixty-five illustrations in the book’

● Diana Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’ in Collecting prints and drawings in Europe, c. 1500–1750, edited by Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam, and Genevieve Warwick (Aldershot 2003), p.137

● Ilja M. Veldman, ‘Portrait of the artist as an art collector: Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon’ in Simiolus 38 (2015–2016), pp.228–249 (p.242, citing this volume).

B / 3

Roscius (Julius Hortinus), Emblemata sacra S. Stephani Caelii Montis intercolumniis affixa ([Rome: publisher not identified], 1589)

provenance

● Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092–2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

● William Beckford (1772–1857), re-bound for him by Christian Samuel Kalthoeber

● George Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford and later 5th Duke of Marlborough (1766–1840)

● R.H. Evans, White Knights library: Catalogue of that distinguished and celebrated library, London 7–19 June 1819, p.68, lot 1532 (‘blue morocco, joints’)

● Richard Heber (1773–1833), his note of purchase in the White Knights sale (Bibliotheca Blandfordiana)

● R.H. Evans, Bibliotheca Heberiana; catalogue of the library of the late Richard Heber, Esq., Part VI, 8 April 1835 (15th Day), p.238, lot 3236 (‘blue morocco, Sir Peter Lely’s copy’; link)

● Isaac Comstock Bates (1843–1913), Providence, RI (‘stamp’, presumably Lugt 222f-g; link)

● Ellen D. Sharpe (1861–1953), Providence, RI, her bequest to

● Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, Printing & Graphic Arts Collection, Typ. 525.89.752 (‘stamp’) (link) (link)

citation

● Harvard College Library, Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, Catalogue of books and manuscripts. Part 2, Italian 16th century books, compiled by Ruth Mortimer (Cambridge 1974), II, pp.616–617 no. 447 (‘blue straight-grain morocco by Kalthoeber’, ‘Beckford copy, with the initials of Peter Lely stamped on each engraving, Heber’s note of purchase from the White Knights sale, and stamp of Isaac C. Bates’)

B / 4

Tempesta (Antonio), Metamorphoseon sive Transformationum Ovidianarum libri quindecim, aeneis formis ab Antonio Tempesta Florentino incisi, et in pictorum, antiquitatisque studiosorum gratiam nunc primum exquisitissimis sumptibus a Petro de Iode Antverpiano in lucem editi (Antwerp: Pieter de Jode, 1606)

provenance

● Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092–2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

● Mr A. Goodwin, 39 High Street, Tunbridge Wells

● London, British Museum, 1893,0411.15.1–151 (163*.a.33) (link)

B / 5

Veen (Otto van), Historia septem infantium de Lara (Antwerp: Philip Lisaert, 1612)

provenance

● Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092–2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

● Society of Writers to Her Majesty’s Signet, Edinburgh

● Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of important old master engravings and etchings, London, 11 June 1959, p.36 lot 138 (offered as ‘The Property of the Society of Writers to Her Majesty’s Signet removed from the Signet Library, Edinburgh’, ‘from the Sir Peter Lely collection’, bound in ‘calf, name of artist, on straight-grained morocco inlaid in centre of upper cover, oblong folio’)

● Glasgow, University Libraries, S.M. Add. 14

citations

● Signet Library, A second supplement to the Catalogue of books in the Signet library, 1882–1887, compiled by Thomas Graves Law (Edinburgh 1891), III, p.166 (link)

● Michael Bath, ‘The Proofs of Antonio Tempesta’s Engravings for Historia Septem Infantium de Lara: Glasgow University Library, S.M. Add.14’ in Emblematica: an Interdisciplinary Journal for Emblem Studies 20 (2013), pp.405–413 (wrongly interpreting Lely’s inkstamped monogram as the initials of the printer)

1. Arthur M. Hind, Engraving in England in the sixteenth & seventeenth centuries: a descriptive catalogue. Part II: The Reign of James I (Cambridge 1955), p.289 no. 5. The portrait is lacking also in one of the dedication copies presented to Charles, Prince of Wales (Christie’s, Linley Hall, Shropshire: A Selection from The Library of The Late Sir Jasper & Lady More, London, 9 March 2016, lot 322).

2. ‘Old English morocco gilt, gilt edges… This volume was formerly Sir Peter Lely’s. It has his autograph twice on the fly-leaf of the Spenser, with some sketches; and also on the title of the Tasso’.

3. Book Prices Current 18 (1904), p.578, item 5809 (link).

4. ‘Inscription “P. Lely” on fly-leaf in a 17th century hand… inscription on title [of Tasso] “B.L.’s (or L.B.’s) gift to P. Lely, 1656,” title backed, wants portrait… in 1 vol., old morocco, gilt, g.e., sold not subject to return’.

5. Book Auction Records 19 (1922), p.716.

6. ‘17th century English red morocco, g.e. … From the Library of the celebrated English Painter, Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680), with his Autograph Signature several times repeated’ (link).

7. Offered by Sotheran’s at the ABA Olympia book fair, 26–28 May 2016 (link).

8. Diana Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’ in Collecting prints and drawings in Europe, c. 1500–1750, edited by Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam, and Genevieve Warwick (Aldershot 2003), pp.123–139.

9. The costs of crating and transport are itemised in an account book kept by the Executors, detailing their administration of Lely’s estate (British Library, Add Ms 16,174). The payments ‘To the Joyner for caseing up the Library to be carryed into the Country… 03–07–00’ and ‘For Carriage of the Library 03–10–00’ were made on 25 September 1682 (British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 29 recto).

10. The application of the stamps is described by North in his autobiography, ‘Notes of me’ (British Library, Add Ms 32,506; published as Notes of me: the autobiography of Roger North, edited by Peter Millard, Toronto 2000, p.244). For the lettered inkstamps, see Fondation Custodia, Frits Lugt: Les marques de collections de dessins & d’estampes, online edition, L.2092–2094.

11. The Executors’ account book indicates that twenty-four ‘Portfolios’ of prints and an unspecified number of ‘Books of prints bound’ were sold in 1688, for a total of £597–18–6. Of that sum, ‘Books of prints bound’ amounted to £29–4–6 (British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 85 verso). Diana Dethloff, ‘The Executors’ Account Book and the dispersal of Peter Lely’s collection’ in Journal of the History of Collections 8 (1996), pp.15–51.

12. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., p.244.

13. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., p.244.

14. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., p.244.

15. Joannes Moerman, Apologi creaturarum ([Antwerp]: [Christopher Plantin for Gerard de Jode], 1584), in Amsterdam University Library; Antonio Tempesta, Metamorphoseon sive Transformationum Ovidianarum libri quindecim (Antwerp: Pieter de Jode, 1606), in British Museum, 1893,0411.15.1–151 (163*.a.33).

16. Jan de Bisschop, Signorum veterum icones [and] Paradigmata graphices variorum artificum (The Hague 1671), in London, Brinsley Ford collection; Julius Hortinus Roscius, Emblemata sacra S. Stephani Caelii Montis intercolumniis affixa ([Rome: publisher not identified], 1589), in Houghton Library, Harvard University, Typ. 525.89.752; Otto van Veen, Historia septem infantium de Lara (Antwerp: Philip Lisaert, 1612), in Glasgow, University Libraries, S.M. Add. 14.

17. See Anthony Griffith’s note, ‘False margins and fake collector’s stamps’ in Print Quarterly 13 (1996) pp.184–187, describing two albums in the British Museum (164.a.2 and 164.b.1), both from the Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode bequest. In these albums, prints from Lely’s collection are mixed with impressions obtained elsewhere.

18. Gaspars arrived in England in 1649, however according to a near-contemporary account, he did not enter Lely’s studio until after the Restoration. Cf. Bainbrigg Buckeridge, ‘An Essay towards an English-School, with the lives and Characters of above 100 painters’ in Roger de Piles, The art of painting, and the lives of the painters (London 1706), p.400 (link). The Executors’ accounts record a payment on 22 December 1681 ‘To Mr Baptist for praising the collection with Mr Walton… 2–3–0’ (British Library, Add Ms 16174, f. 29 verso).

19. Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1655–6, edited by Mary Anne Everett Green (London 1882), p.583: warrant for passports ‘For Peter Lely and Hugh May, his servant, to Holland, on request of Lord Strickland’ granted 29 May 1656 (link). John Bold, ‘May, Hugh’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, Jan 2008, accessed 22 November 2016), states the purpose of their visit ‘to join the exiled court’.

20. Several years earlier, in 1652, Peter Lely and his sister had jointly inherited a property in The Hague from an aunt, Odilia van der Faes. Catharina Maria was a prime beneficiary of Lely’s will.

21. Lely’s monogram on his black chalk Portrait of John Lely, as a child, British Museum, 1874,0808.2264 (link). Oliver Millar, Sir Peter Lely 1618–80 [catalogue of the] e xhibition at 15 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1 [from 17 November 1978–18 March 1979] (London 1978), p.80 no. 83.

22. Lely’s monogram on his black chalk Portrait of Anne Lely, as a child, British Museum, 1874,0808.2265 (link). Millar, op. cit., p.80 no. 84.

23. Lely’s monogram on his black and white chalk Portrait of a girl, drawn in the late 1650s, British Museum 1983,0723.35 (link; Lindsay Stainton and Christopher White, Drawing in England from Hilliard to Hogarth, catalogue of an exhibition held at the British Museum, June-August 1987, London 1987, pp.123–124 no. 88).

24. David A.H.B. Taylor, ‘Lely in Arcadia: Religious, pastoral, musical and mythological themes in Peter Lely’s subject pictures’ in Peter Lely: a lyrical vision, edited by Caroline Campbell, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Courtauld Gallery, London, 11 October 2012–13 January 2013 (London [2012]), pp.63–85 (citing Lely’s Spenser / Tasso on p.67); Clare Barron, ‘Sir Peter Lely and the Sister Arts: Painting, poetry and music’ in ‘Teachers’ resource – Peter Lely: a lyrical vision’, CD compilation for the exhibition held at The Courtauld Gallery, 2012–2013, edited by Naomi Lebens and Joff Whitten (online resource).

25. Millar, op. cit., p.70 no. 56. Also at Lamport is a portrait of Thomas Isham by John Baptist Gaspars.

26. A copy of the 1632 second folio Shakespeare, with its dedication leaf inscribed ‘The Lady Vere Isham’s book from Mr. Peter Maidwell [rector of Shangton, a Leicestershire living in the gift of Sir Justinian, from 1669–1684]’ is in the library at Lamport Hall. The two inscriptions require comparison.

27. Robert E. Graves, ‘The Isham books’ in Bibliographica 3 (1897), pp.418–429; William A. Jackson, ‘The Lamport Hall-Britwell Court Books’ in Joseph Quincy Adams Memorial Studies, edited by James G. McManaway (Washington, DC 1948), pp.587–599, reprinted in Records of a Bibliographer: Selected Papers of William Alexander Jackson, edited by William H. Bond (Cambridge 1967), pp.121–133. Of the 130 books listed by Jackson, only 13 were published after Thomas’s death in 1605.

28. On the two versions of the exlibris, see Walter Hamilton, Dated book-plates (Ex libris) with a treatise on their origin and development (London 1895), p.69 (link); Gyles Isham, ‘The Correspondence of David Loggan with Sir Thomas Isham – II’ in The Connoisseur 154 (October 1963), pp.86, 90 (note 49). Gerald Burdon, ‘Sir Thomas Isham: an English collector in Rome, 1677–8’ in Italian Studies 15 (1960), pp.1–25 (esp. pp.17–18; list of purchases in Appendix A); Anne Brooks, ‘Richard Symonds and Thomas Isham as collectors of prints in seventeenth-century Italy’ in The evolution of English collecting: receptions of Italian art in the Tudor and Stuart periods, edited by Edward Chaney (New Haven 2003), pp.337–395. A selection of these books and prints was exhibited at Central Art Gallery, Northampton, 12 July–9 August 1969: Sir Thomas Isham: an English collector in Rome, 1677–8, catalogue by Sir Gyles Isham and Gerald Burdon ([Northampton] 1969), p.[15], list of 17 volumes, including editions in Italian of Tasso, Boccaccio, and Dante, some inscribed ‘T. Isham’ or with his engraved exlibris.

29. Charles Edmonds, An annotated catalogue of the library at Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, the seat of Sir Charles E. Isham, Bart. including copious notes and observations on the rare, unique, and hitherto-unknown books of English poetry, early English plays, and prose works, as well as on other interesting books and manuscripts preserved therein ([England: publisher not identified], 1880), p.5: ‘Various autograph signatures… Sir Peter Lely (who painted the Portrait of Sir Thomas Isham), with a pen sketch by him, and the Initials of Miss Vere Isham, in Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Jerusalem’.

30. H.A.N. Hallam, ‘Unfamiliar libraries XII: Lamport Hall revisited’ in The Book Collector 16 (1967), pp.439–449 (p.448: ‘There was, for instance, a volume of Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata 1621, bound with Spenser’s Faerie Queen 1617. This contained the signature of Sir Peter Lely, who painted the portrait of Sir Thomas Isham, of which there are two versions in the house, with a pen sketch by him. This volume, which realized two guineas only, has disappeared from view after its sale in 1921 to a dealer who has since died’.)

31. Douglas Gordon, ‘The Book-Collecting Ishams of Northamptonshire and Their Bookish Virginia Cousins’ in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 77 (1969), pp.174–179 (appearance in 1904 sale cited p.176); a revision (delivered as Third George Parker Winship Lecture, 4 December 1969) printed in Harvard Library Bulletin 18 (1970), pp.282–297 (suggesting p.288 that Lely ‘perhaps left [the book] behind at Lamport Hall’).

32. The payment in the Executor’s account book is dated 14 December 1681 (British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 26 verso).

33. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Volume IX, 1668–1669, edited by Robert Latham and William Matthews (London 1976), p.480 (12 March 1669).

34. Howard M. Nixon, English Restoration bookbindings: Samuel Mearne and his contemporaries (London 1974), pp.32–34, nos. 56–64; H.M. Nixon, ‘Queens’ Binders A & B’ in Sotheby Parke Bernet & Co., Catalogue of valuable books, London, 16–17 November 1981, pp.53–55 (rubbings of 21 and 10 tools associated respectively with Queens’ Binders A and B); H.M. Nixon, Catalogue of the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. Volume 6: Bindings, compiled by H.M. Nixon (Cambridge 1984), plates 40–43.

35. Alan Stevenson, in Charles Moïse Briquet, Les filigranes (Amsterdam 1968), I, p.*35.

36. A paper with the same arms and subscript ‘A Durand’ is in the Folger Library, E. Williams watermark collection, L.f.733 (letter of attorney, 15 July 1651; link); comparable marks are reproduced by Edward Heawood, Watermarks, mainly of the 17th and 18th centuries (Hilversum 1950), nos. 661 (c. 1673), 678 (1680); Idem, ‘Further notes on paper used in England after 1600’ in The Library, fifth series, 2 (1947–1948), p.144 no. 22 (Raleigh’s History 1677).

37. Steven K. Galbraith, ‘Spenser's First Folio: The Build-It-Yourself Edition’ in Spenser Studies 21 (2006), pp.21–49 (revision of the fourth chapter of his PhD dissertation: Edmund Spenser and the History of the Book, 1569–1679, The Ohio State University, 2006, pp.158–181; link).

38. F.R. Johnson, A Critical Bibliography of the Works of Edmund Spenser Printed Before 1700 (Baltimore 1933), pp.33–48.

39. ‘Sir, The command of his Maieste, seconded by your Highnesse, hath caused mee to renew the impression of this booke. The former edition had the honour to be dedicated to the late Queene Elizabeth, of famous memorie, as appeareth by a worthy Elogie, here preserved. I could not leave this second birth of so excellent an Author, without a living Patron; and none could be found fitter than your Princetly self, who as you have highly commended it, so it is to be presumed, you will take it into your safe and Princely protection’.

40. Godfrey of Bulloigne: a critical edition of Edward Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, together with Fairfax's original poems, by Kathleen M. Lea and T.M. Gang (Oxford 1981), p.67, based on a collation of 18 copies of the first edition and of these with the second.