Printed at the author’s private press in Vigevano

Architectura civil recta, y obliqua. Considerada y dibuxada en el Templo de Ierusalen. Erigido en el Monte Moria por el Rey Salomon. Destruido por Nabucodonosor Emperador de Babylonia. Reedificado por Zorobabel Nieto de los Reyes Iudos. Y restaurado despues por el Rey Herodes. Y ultimamente convertido en cenizas por los Soldados de Tito Hijo de Vespasiano Emperador. Promovida a suma perfeccion en el templo y palacio de S. Lorenço cerca del Escurial

- Subjects

- Architectural books - Early works to 1800

- Architecture, Spanish - Early works to 1800

- Book illustration - Artists, Italian - Bugatti (Giovanni Francesco), active 1670-1695

- Book illustration - Artists, Italian - Durelli (Simone), active 1660-1704

- Book illustration - Artists, Italian - Laurentio (Cesare), 1657-1689

- Perspective - Early works to 1800

- Authors/Creators

- Caramuel Lobkowitz, Juan, 1606-1682

- Artists/Illustrators

- Bailliu, Barend de, active 1641-1678

- Bugatti, Giovanni Francesco, active 1670-1695

- Durelli, Simone, active 1660-1704

- Laurentio, Cesare, 1657-1689

- Printers/Publishers

- Corrado, Camillo, active 1678

- Owners

- Macclesfield, Earls of

Caramuel Lobkowitz, Juan

Madrid 1606 – 1682 Vigevano

Architectura civil recta, y obliqua. Considerada y dibuxada en el Templo de Ierusalen. Erigido en el Monte Moria por el Rey Salomon. Destruido por Nabucodonosor Emperador de Babylonia. Reedificado por Zorobabel Nieto de los Reyes Iudos. Y restaurado despues por el Rey Herodes. Y ultimamente convertido en cenizas por los Soldados de Tito Hijo de Vespasiano Emperador. Promovida a suma perfeccion en el templo y palacio de S. Lorenço cerca del Escurial.

Vigevano [Italy], ‘En la Emprenta Obispal por Camillo Corrado’, 1678

Three parts bound in one volume, folio (365 × 220 mm):

i: (146) ff. signed *4 **4 A4 (blank A4) A–C4 A–G4 H2 (blank H2)A–I4 a–d4 e6 A–H4 I2 and paginated (24) 1–24, 1–58 (2), 1–71 (1), (44), 1–68. contents folio *1 recto title-page, verso engraved vignette (arms of dedicatee); *2 recto dedication to Don Juan José de Austria, verso ‘Refierese en general lo que se contiene en este libro’; *3 recto –**4 verso ‘Orden de los tratados, articulos y secciones en que estos dos tomos se dividen’; A1 recto –A3 verso ‘Catalogo de los Libros que tiene impressos o esta actualmente imprimiendo el Ill. y Rev. S. don Iuan Caramuel [compiled by Domenico Piatti]’; A4 blank; A1 recto and verso ‘Libros que ha de procurar tener en su Bibliotheca un Architecto’; A2 recto–C4 verso ‘Discurso Mathematico de D. Ioseph Chafrion’; A1 recto–H3 verso ‘Tratado proemial’; H4 blank; A1 recto–I4 recto ‘Tratado i [–iii]’; a1 recto–e6 verso ‘Tablas Mathematicas’; A1 recto–I2 verso ‘Tratado iv’. Large woodcut ornaments, including a putto with a compass (title-page), a representation of the Virgin in Glory (folio A3 verso), and the author’s armorial insignia (D2 recto, G3 recto repeated H2 verso); initials from several alphabets, including a large D featuring a portrait of the author (2A1 recto).

ii: (150) ff. signed π2 A–L4 A–I4 K2 L4 M2 A–N4 O2 P4 Q2 (blank Q2) and paginated (4) 1–88, 1–77 (11), 1–109 (11). contents folio π1 recto title-page ‘Tomo ii’, verso blank; π2 recto and verso dedication to Don Juan José Austria; A1 recto–L3 verso ‘Tratado v’; L4 recto ‘Chilias Logarithmorum musicorum’, verso ‘Scala Musica’; A1 recto–E4 recto ‘Tratado vi’; E4 verso–L1 recto ‘Tratado vii’; L1 verso–M2 verso ‘Indice General’; A1 recto–H3 recto ‘Tratado viii’; H3 verso–P1 recto ‘Tratado ix’; P1 verso–Q1 verso ‘Tabula Segunda de las Cosas Notables’; Q2 blank. Large woodcut ornaments, including a putto with a plumb-line (title-page), and initials from several alphabets, one of which features the Virgin of Montserrat (folio π2 recto, 2E4 verso, 3A1 recto).

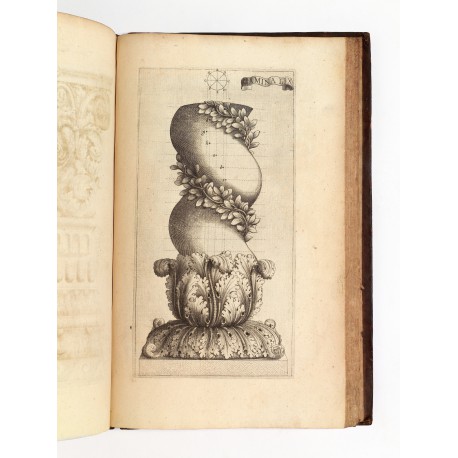

iii: (4) ff. letterpress signed π4, not foliated or paginated; plus 161 engraved plates. contents (letterpress): folio π1 recto title-page ‘Tomo iii ’, verso blank; π2 recto and verso dedication to Don Juan José de Austria; π3 recto–π4 verso ‘Tabla general’. Contents (plates): engraved part-title ‘Parte i. En que se ponen las Orthographias de los Edificios, Altares y Vasos del Templo de Ierusalem’ and eight engraved plates designated ‘Lamina A’ [–H]; engraved part-title ‘Parte ii. En que se contienen las Figuras que conciernen a la Calographia, Arithmetica, Geometria, &c’ and forty-nine engraved plates designated ‘Lamina i’ [–ii, iii prior, iii posterior, iv–xlviii]; engraved part-title ‘Parte iii. En que con sus verdaderas medidas, se dibujan y pintan, no solo los Ordenes Antiguos de Colunas, que en la Architectura Recta labraron los mejores Ingenieros de Grecia’ and fifty-nine plates designated ‘Lamina i’ [ii/iii/iv, v/vi, vii/viii, ix, x/xi/xii, xiii–xxvii, xviii prior, xxviii posterior, xxix–lxiiii]; engraved part title ‘Parte iv. En que con curiosidad se describen y miden las Prostaphereses y Parallaxes con que la Architectura Obliqua’ and forty-one plates designated ‘Lamina i’ [–xli]. Woodcut ornament of a putto with a square and insignia of the dedicatee (folio π2 verso).

early issue, published before completion of an engraved title-page (lettered Templvm Salomonis rectam et obliqvam architectvram exhibens Inventore et Auctore D. Ioanne Caramuel An. m.dc.lxxviii), and portrait plates of the author (lettered D. Ioannes Caramuel Episcopus Viglevanensis. Io Fran.cus Bugattus Mediolanens. sculp. anno 1679) and dedicatee, Don Juan José de Austria (lettered D. Ioannes Austriacvs Serenissimvs Princeps | Jo. Fran.cus Bugattus sculp).

provenance Earls of Macclesfield, Shirburn Castle, embossed stamp on first three leaves, exlibris on paste down South Library dated 1860 and inscribed with shelfmark 114 G 17 (earlier shelfmark iii 2.3 inscribed in ink on pastedown) — Sotheby’s, ‘The Library of the Earls of Macclesfield, Part Ten: Applied arts and science’, London, 30 October 2007, lot 3396

Paper flaw in one leaf (part 2, folio 1 I4), without loss; light waterstaining in some lower margins; otherwise a very well-preserved copy. Binding rubbed, lower joint cracking.

bound in contemporary English calf, covered ruled in blind with ornaments in the angles; back divided by raised bands into six compartments and decorated in gilt; lettering-piece Caramueli | Architectura | Civil .

First printing of the most ambitious Spanish architectural treatise to date, a provocative work in which the author argues the superiority of ‘oblique’ architecture to ‘straight’ (Vitruvian) architecture, and famously censures Bernini’s designs for the colonnade around St. Peter’s Square and staircase (Scala Regia) in the Vatican, and equestrian statue of the Emperor Constantine (the later spoilt, Caramuel argued, by the height at which it was placed). Caramuel’s obsession with geometry and optical distortion was treated as madness by some contemporaries; others, such as the architect and theoretician Guarino Guarini, ‘who carried on with Caramuel intensive discussions as he did with no other theorist’,1 took him very seriously. Intended for Spanish readers, the treatise had greatest impact in Catalonia and in the New World, where Caramuel’s ideas were spread by theologians and mathematicians, and examples of ‘architectura obliqua’ are numerous.2

The astonishing range and sheer volume of Caramuel’s writings (he is author of at least seventy published works) together with the fact that the only constructions he completed were the square and façade of the cathedral at Vigevano, have impeded recognition of the originality of his theoretical contribution to architecture.3 According to the author’s own account, he mastered architectural techniques with Cistercian monks as a young novice at the Monasterio de la Santa Espina (Valladolid), began writing this treatise in 1624, and in 1635 commenced production of the 161 copper matrices eventually used for its illustration.4

The book is the first of eight issued under the imprint ‘En la Emprenta Obispal por Camillo Corrado’ (or ‘Typis Episcopalibus apud Camillum Conradam’) at the Italian town of Vigevano, where Caramuel was bishop from 1673 until the end of his life. In his previous diocese (Campagna and Satriano), Caramuel had also instituted a private press, operated by Sebastiano Alecci under the imprint ‘Ex typographia episcopali Satrianensi’ (or version thereof). Corrado and Alecci were in no sense diocesan printers; both worked exclusively for Caramuel, and their publications are truly private-press books. Like many such books, they were not widely distributed, and today are of notable rarity.

The long-gestated Architectura civil recta, y obliqua begins with a ‘Tratado proemial’ on the Temple of Jerusalem as an example of ‘oblique’ architecture. Elsewhere, Caramuel digresses into a history of world architecture encompassing the pyramids, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, and indigenous architecture from the New World (including Hochelaga, an Iroquoian fortified village on the site of pre sent-day Montréal, Quebec), and concludes that the first architects (‘Los primeros Maestros de obras’) built oblique architecture exclusively.5 He pronounces Juan de Herrera’s Escorial the supreme modern embodiment of oblique architecture,6 the indisputable peak of architectural wisdom, and eighth ‘wonder’ of the modern world (in the 1681 Latin edition, aimed at an international audience, this hispanophilism was toned down markedly).7

The character of the architect and all the knowledge he must possess in order to design a building, particularly mathematics (including the application of logarithms in architecture, comparing Napier’s, Brigg’s, and the author’s own systems),8 is set forth in Books i–iv ; in Book v, ‘architectura recta’, or architecture built according to the authority of the learned, is introduced; and finally, in Book vi, commences the important part of the work, the discussion of ‘architectura obliqua’, or architecture according to what is dictated by (mathematical) reason, regardless of convention, in which Caramuel challenges the authority of the ancients and critiques modern architects.

Book vii is devoted to painting, sculpture, physiognomy, perspective, fortification, and music (the last recommended to students of architecture, but not one of the sciences ‘precisamente necessarias’); Book viii to ‘architectura practica’, with further discussion of buildings in Rome; and the concluding and hastily-redacted Book ix provides glosses and commentaries to the plates.

The illustrations are grouped together and organised in four parts: eight plates show the Temple of Jerusalem (Villalpando’s model is rejected in favour of the asymmetrical reconstruction of Jacob Juda León); forty-nine plates accompany the discussion of the sciences useful to architects; fifty-nine plates illustrate either ‘architectura recta’ or Caramuel’s improvements (he presents eleven different orders of columns);9 and forty-one plates explicate the laws of ‘architectura obliqua’, including a series showing how to determine the optical distortions of sculptures (a reclining figure and a sphinx) (see Fig. 5) and two plates censuring Fernando de Valenzuela’s placement (1676–1677) of Philip iv’s equestrian statue by Pietro Tacca – originally planned for a garden – on top of the main façade of Madrid Alcazar (see Figs. 6–7).

The majority of the engravings are by anonymous printmakers: one print is signed by the Roman engraver Bernard Balliu (part 4, pl.6), five by the Milanese engraver Giovanni Francesco Bugatti (fl. 1670–1695),10 seven by Cesare Laurentio (fl. 1657–1689),11 and eleven by the Milanese printmaker Simone Durello (1641–1719).12 With the exception of a few plates of architectural inscriptions, the forty-nine plates illustrating part 2 are re-struck from matrices used for Caramuel’s Mathesis biceps, vetus, et nova, printed at Campagna ‘in Officina Episcopali’, in two volumes, 1667–1670; woodcut initials and ornaments made for that book are also reused. The four engraved part-titles organising the plates are struck from a single matrice, also used for the Mathesis nova, here adapted by deleting the original title, imprint and dedicatee’s insignia, and substituting Corradi’s imprint, Caramuel’s own heraldic insignia, adding the title (now by letterpress), and altering the date.

Variations between copies signify different issues within the edition. An engraved vignette (platemark 132 × 184 mm) displaying the heraldic insignia of the dedicatee, the Spanish illegitimate prince Don Juan José de Austria, occurs on the verso of the title-page (part 1) in our copy (and also the British Library copy); in all other copies we have examined, the page is blank. It seems that only copies without the vignette contain a portrait of Caramuel by Bugatti, dated 1679, among the preliminaries of part 1; this portrait must have been a late addition, and the copies containing it therefore represent a subsequent issue of the edition.13 The date of first issue is uncertain: it could be 1678, which is the date printed on the title and sub-titles; or 1679; or even later, since a list of the author’s ‘Libros impressos’ (printed among the preliminaries of part 1, folio A2 verso) includes two works published in the later year (nos.38/39 and 40/42, ‘imprime este mismo año de 1679 en la Ciudad de Vegeven’).14

Two other plates can occur among the preliminaries in part 1: an engraved frontispiece, representing a simplified version of Bernini’s ‘Baldacchino’ of St. Peter’s in Rome, lettered Templvm Salomonis rectam et obliqvam architectvram exhibens Inventore et Auctore D. Ioanne Caramuel An. m.dc.lxxviii; and a portrait of the dedicatee, Don Juan José de Austria (d. 17 September 1679). Neither plate was ever present in our copy, nor apparently in the British Library copy (rebound in recent years); however, until additional copies have been examined, it is impossible to say whether the absence of these two plates should be regarded as an imperfection or as an issue point.

Although not truly rare – we locate twenty-four substantially complete copies worldwide, the majority held in libraries in Spain and Italy – this book is famously difficult to obtain ‘complete’ and in good condition, and its absence from collections of architectural books developed over many years, such as the riba /British Architectural Library, Fowler Collection of Early Architectural Books at Johns Hopkins University Library, and Canadian Centre for Architecture, is telling evidence of the difficulty of procuring a copy.15 To our knowledge, only one other copy has appeared in auction sale rooms in the last seventy years.16 The copies known to the writer are these:

presumed early issue (without frontispiece, with engraved vignette on verso of title-page, without portraits ● the copy here offered for sale ● London, British Library, 559 *f 9

presumed intermediate issue (with frontispiece, without vignette on verso of title, with portrait of Don Juan, without portrait of Caramuel) ● Cambridge, ma, Harvard University, Houghton Library, Typ 625.78.260 F ● Cambridge, ma, Harvard University, Houghton Library, FA 1545.215 F* ● London, National Art Library at the Victoria & Albert Museum, 31 G. 1–3 ● Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute, Muzio Collection, 93–B6775 ● Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, Biblioteca, Mad. 252-25417 ● New York, Columbia University, Avery Architectural Library, AA 2515 C17

presumed late issue (with frontispiece, without vignette on verso of title, with portrait of Don Juan and portrait of Caramuel) ● Sotheby’s, ‘Livres et manuscrits, incluant les archives K éditeur’, Paris, 9 June 2004, lot 9 ● unspecified copy utilised for facsimile edition (Madrid: Ediciones Turner, [1984])

undetermined issue ● Albany, New York State Library, 720 fC259 ● Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2° Ny 4642 ● Castell de Sant Miquel d’Escornalbou (formerly)18 ● Córdoba, Bibliotheca Diocesana Cordubensis, Est 305.092 ● Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Ant. Jud. 50 ● Einsiedeln, Stiftung Bibliothek Werner Oechslin19 ● Florence, Biblioteca Marucelliana, 5 ci 1320 ● Freiburg im Breisgau, Universitätsbibliothek, F 1607–1/3 ● Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, R/2488721 ● Madrid, Universidad Complutense, BH FIL 1256622 ● Milan, Biblioteca Comunale, Palazzo Sormani, VET.X VET.95.2 ● Milan, Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, VV XI 2323 ● Milan, Biblioteca Trivulziana ● Novarra, Biblioteca comunale Carlo Negroni ● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, V–2058 ● Pavia, Biblioteca Universitaria Alessandrina, 26 E 2224 ● Rome, Bibliotheca Angelica, i.9.9–1025 ● Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, M. IV. 1. 1–326 ● St. Bonaventure, ny, University Library, Franciscan Institute, F 10,185 ● San Francisco, California State Library, Sutro Library, f NA251.C37 ● Santiago de Compostela, Biblioteca Universitaria27 ● Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Cicognara VII 46328 ● Vigevano, Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile29

References

Architectural theory: from the Renaissance to the present: 89 essays on 117 treatises with a preface by Bernd Evers and an introduction by Christof Thoenes; in cooperation with the Kunstbibliothek der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (Cologne & London 2003), pp.386–397 (eleven plates reproduced)

bonet correa

Antonio Bonet Correa, Bibliografía de arquitectura, ingeniería y urbanismo en España (1498–1880) (Madrid & Vaduz 1980), no. 317

El Libro de arte en España, catalogue of an exhibition held in the Hospital Real de Granada, xxiii Congreso Internacional de Historia del Art, 3–8 September 1973 ([Granada] [1975?]), pp.64–65 no. 94 (copy described in ‘Biblioteca Nacional’, apparently r/24887)

lucas

Florentino Zamora Lucas, Bibliografía española de arquitectura (1526–1850), Publicaciones de la Asociación de Libreros y Amigos del Libro, 3 (Madrid 1947), pp.78–79 no. 69 (copy described in ‘Biblioteca Nacional’, apparently r/24887)

serrai

Alfredo Serrai, Phoenix Europae. Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz in prospettiva bibliografica (Milan 2005), pp.266–268, no. 78

schmutz

Jacob Schmutz, Bibliographia caramueliana: Inventaire général des oeuvres de Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz (1606–82) et bibliographie critique (2005), no. 50 (online resource: http://pagesperso-range.fr/caramuel/index.html)

vagnetti

Luigi Vagnetti, De naturali et artificiali perspectiva: bibliografia ragionata delle fonti teoriche e delle ricerche di storia della prospettiva (Florence 1979), p.415 no. EIII–B67

abbreviations below are expanded in references

1. Werner Oechslin, in Architectural theory and practice from Alberti to Ledoux, catalogue of an exhibition, edited by Dora Wiebenson ([Chicago] 1983), ii–7; Joan-Ramon Triadó, ‘Perspectiva y escenografía barroca: Catalunya y Sicilia. Caramuel versus Guarino Guarini’ in Sicilia barocca: maestri, officine, cantieri, edited by Ferdinando Maurici and Gianni Eugenio Viola (Rome 2005), pp.133–148.

2. David Manuel Vilaplana Zurita, ‘Influencias del tratado de Caramuel en la arquitectura de la Colegiata de Xàtiva’ in Archivo de arte valenciano 66 (1985), pp.61–63; Carlos Chafón Olmos, ‘Los tratadistas Simón García y Juan Caramuel: su proyección en la arquitectura novohispana’ in Mensaje de las imágenes, edited by J.A. Terán Bonilla (Mexico 1998), pp.33–54. The application of Caramuel’s theories can be detected also in projects built in Italy, by Filippo Juvarra (staircase of Palazzo Madama in Turin) and Luigi Vanvitelli (planning of Palazzo Reale at Caserta; see The Dictionary of Art, 5, p.701).

3. The standard presentations of Caramuel as an architectural dilettante (espoused by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Werner Oechslin, especially), as seduced by fanciful optical distortions (Kruft and Oeschlin again), and as the antagonist of Bernini (Bruno Zevi), are revised in two recent publications by Jorge Fernández-Santos Ortiz-Iribas: ‘The elusive role of perfection in architecture: Caramuel’s Raptus Geometricus reconsidered’ in Ad limina ii: incontro di studio tra i dottorandi e i giovani studiosi di Roma, Istituto Svizzero di Roma, Villa Maraini, febbraio–aprile 2003, edited by Renate Burri (Alessandria 2004), pp.363–385; and ‘Classicism Hispanico more: Juan De Caramuel’s presence in Alexandrine Rome and its impact on his architectural theory’ in Annali di architettura 17 (2005), pp.137–165. See also Filippo Camerota, ‘Architecture as mathematical science: the case of “Architectura Obliqua”’ in Practice and science in early modern Italian building: towards an epistemic history of architecture, edited by Hermann Schlimme (Milan 2006), pp.51–60.

4. Part 2, ‘Tratado vi’, p.2. The treatise is first announced in the ‘Omnium operum Caramuelis catalogus’ in Caramuel’s Theologia moralis fundamentalis (Frankfurt am Main 1652), p.5.

5. Joseph Rykwert, On Adam’s house in paradise: the idea of the primitive hut in architectural history (Cambridge, ma 1981), pp.135–140; Alberto Pérez Gómez and Louise Pelletier, Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge (Cambridge, ma 1997), pp.125–129, 145–158.

6. Carlo Peña Buján, ‘¿Diseñó Dios el Escorial?: Caramuel, el solomonismo y la octavia maravilla’ in Studi Secenteschi 46 (2005), pp.259–280.

7. According to available descriptions, the Latin edition is a folio of 184 leaves, paginated [xx], 60, [44], 243 plus a portrait of the author and 140 plates. In some copies, the engraved frontispiece of the 1678 edition (lettered Templum Salomonis rectam et obliquam architecturam exhibens) serves as title-page; in others, the title ‘Mathesis architectonica’ is supplied. Two copies are described by Paolo Pissavino and Alessandra Bracci, ‘L’occaso del sole e i suoi frutti: Il catalogo delle opere di Juan Caramuel conservate nella Biblioteca del Seminario vescovile di Vigevano’ in Bollettino della Società Pavese di Storia Patria 34 (1982), p.125; another is located by the Catálogo Colectivo del Patrimonio Bibliográfico (ccpb) in the Biblioteca Pública de León (Fondo Antiguo 5809; ‘Falto de port.’); and schmutz, ‘Elenchus Operum’, no. 58, locates a fourth copy in ‘Milano BSB’ (presumably Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, but not in its opac). No other copies are known (serrai p.285: ‘List c. Titoli delle edizioni delle opere di Caramuel da rintracciare. L’esistenza di alcune edizioni è soltanto ipotetica’). Differences between the Spanish and Latin editions are cited by Jorge Fernández-Santos Ortiz-Iribas, ‘Austriacus re rectus obliquâ: Juan Caramuel y su interpretación oblicua del Escorial’ in El Monasterio del Escorial y la arquitectura: actas del simposium, edited by F. Javier Campos and Fernández de Sevilla (San Lorenzo del Escorial 2002), pp.393 (note 13), 402–403 (notes 53–55).

8. Juan Navarro-Loidi and José Llombart, ‘The introduction of logarithms into Spain’ in Historia Mathematica 35 (2008), pp.83–101.

9. Carlos Pena Buján, ‘Dórico, jónico, corintio y ocho órdenes más: la interpretación caramueliana de un sistema clásico’ in Actas del xi Congreso Español de Estudios Clásicos, edited by Antonio Alvar Ezquerra (Santiago de Compostela 2005), iii, pp.531–538.

10. Part 3/i, plates F, G; part 2, plate 1; part 3, plate 24. Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon: die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker, 15 (Munich & Leipzig 1997), pp.75–76.

11. Part 3 /i, plates A, B, C, E, H; part 3, plates 53, 58. Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker (Leipzig 1907–1950), xxii, p.453.

12. Part 3/i, plate D; part 3, plates 23, 38, 52, 57, 61, 62 ; part 4, plates 28, 34, 35, 36. Fabrizia Triaca-Fabrizi, ‘Simone Durello, incisore lombardo (1641–1719)’ in Rassegna di Studi e di Notizie [Castello Sforzesco, Comune di Milano] 13 (1986), pp.708, 729 (note 19), 732 (note 57) and fig. 14. An unsigned engraving (Part 3/iv, xxiv) is assigned to Durello on stylistic grounds and dated 1673–1678 by Fernández-Santos, op. cit., 2005, pp.146, 163 (note 140).

13. Cf. online resource of the ‘Centro Virtual Cervantes. Fortuna de España. Ciencia’, ‘Descripción catalográfica’ (http://cvc.cervantes.es/obref/fortuna/expo/ciencia/obras.htm): ‘En vuelto de portada escudo de don Juan de Austria… Salvá no hace mención del retrato del autor que incluyen otros ejemplares. Se trata no obstante de un grabado realizado por el grabador Franciscus Bugattus en 1679 y añadido con posterioridad’.

14. Another list of the author’s publications, printed circa 1679, dates the first part 1678 and the other two 1679 (‘Et excuduntur nunc Viglevani, in Episcopali Palatio, anno 1679’); see Opera omnia, quae prodierunt in lucem: interseruntur etiam libri aliqui, qui ultimam manum subierunt, & lucem opportunam exspectant (Biblioteca universitaria di Pavia, Miscellanea in-folio, Tomo xvi; reproduced in facsimile in La bancarella dell’enciclopedista Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz, 1606–1682: mostra bibliografica, 4 dicembre 2006-27 gennaio 2007, edited by Paolo Pissavino (Como 2006), pp.[v–vi]).

15. No copy in the Library of the Hispanic Society of America, according to Clara L. Penney, Printed Books, 1468–1700 in The Hispanic Society of America (New York 1965). The two ‘copies’ reported at Yale University and University of California – Davis are in fact photocopies produced from microfilm.

16. Sotheby’s, ‘Livres et manuscrits, incluant les archives K éditeur’, Paris, 9 June 2004, lot 9 (€28,800). Fragments were sold by Christie’s, ‘Important printed books and an illuminated manuscript’ [Stirling-Maxwell library], London, 20 May 1958, lot 140 (part 3 only, sold £22 to Nico Israel); Sotheby’s, ‘Catalogue of printed books’, London, 23 October 1979, lot 518 (part 3 only); Bloomsbury Auctions, ‘Catalogue of printed books’, London 20 July 2007, lot 497 (part 1 only, without portrait of Caramuel); Reiss & Sohn, ‘Auktion 118: Wertvolle Bücher’, Königstein im Taunus, 22 April 2008, lot 1804 (part 3 only).

17. Bibliotheca Artis. Tesoros de la Biblioteca del Museo del Prado, catalogue of an exhibition held at Museo del Prado, Madrid, 5 October 2010–30 January 2011, edited by Javier Docampo (Madrid 2010), p.73 no. 23.

18. Eduart Toda y Güell, Bibliografía Espanyola d’Italia dels origens de la imprempta fins a l’any 1900 (Castell 1927–1931), i, pp.323–325, no. 923: ‘vers de la portada, escut reyal d’Espanya gravat en coure’ and portrait of Don Juan José de Austria.

19. Located on opac of Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (eth), Zürich.

20. Reproductions (figs. iii, I, D) in Triaca-Fabrizi, op. cit.

21. This is the Vincente Salvá — Riccardo Heredia copy, in a modern binding of green cloth. It is probable that a portrait has been inserted from another copy; compare Pedro Salvá y Mallen, Catalogo de la biblioteca de Salvá (Valencia 1872), ii, 360–361 no. 2563; and Catalogue de la bibliothèque de M. Ricardo Heredia (Paris 1894), iv, p.117 no. 4815, and the library’s cataloguing: ‘Falto de h. de grab. con retrato del autor’ (online Catálogo Colectivo del Patrimonio Bibliográfico Español); ‘En vuelto de portada escudo de don Juan de Austria… Salvá no hace mención del retrato del autor que incluyen otros ejemplares. Se trata no obstante de un grabado realizado por el grabador Franciscus Bugattus en 1679 y añadido con posterioridad’ (‘Descripción cátalográfica’, cf. ‘Centro Virtual Cervantes’ (ciencia/obras.htm). The copy is accessible in the Library’s ‘Biblioteca Digital: Libros antiguos hasta 1830’ (http://www.bne.es/cgi-bin/wsirtex?FOR=WBNCONS4).

Three incomplete copies in the Biblioteca Nacional de España are recorded by ccpb and also in the Catálogo colectivo del patrimonio bibliográfico español: siglo xvii (Madrid 1992), iii, p.20 no. 2494: 6–i/916 (part 2 only ‘y está falto de las 10 últimas p.’), 8/19726 (part 1 only, ‘No lleva grab. en el verso de port.’), er /4821–23 (‘Falto de los tratados viii y ix del t. ii y de la h. de grab. retr. del autor. No lleva grab. en el verso de port.’).

22. Described by Félix Díaz Moreno, ‘Tratados españoles de arquitectura en el fondo antiguo de la Universidad Complutense’ in Anales de Historia del Arte 5 (1995), pp.197–198, 202 no. 10: ‘Desgraciadamente está incompleto, faltando los tratados viii y ix y el volumen de láminas con el que cierra la edición’.

23. Copy cited by Pissavino and Bracci, op. cit., p.111.

24. Copy exhibited in La bancarella dell’enciclopedista, op. cit.

25. Copy located by serrai pp.266–268, no. 78.

26. Copy located by serrai pp.266–268, no. 78.

27. Catálogos: Impresos del siglo xvii, compiled by José María de Bustamante y Urrutia (Santiago 1952), ii, p.91 no. 3752.

28. Leopoldo Cicognara, Catalogo ragionato dei libri d’arte e d’antichità posseduti dal conte Cicognara (Pisa 1821), no. 463.

29. Copy cited by Pissavino and Bracci, op. cit., pp.121–122.