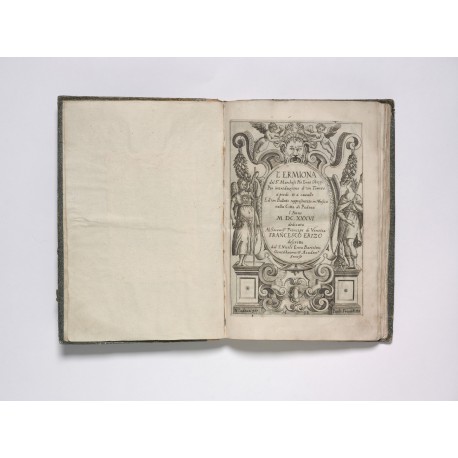

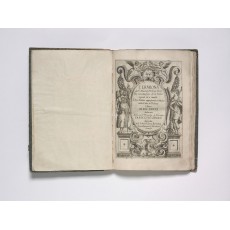

L’Ermiona del S.r Marchese Pio Enea Obizzi. Per introduzione d’vn Torneo à piedi, & à cavallo e d’vn Balletto rappresentato in Musica nella Citta di Padoua l’Anno M DCXXXVI dedicata al Sereniss.o Prencipe di Venetia Francesco Erizo descritta dal S. Nicolò Enea Bartolini, Gentilhuomo, & Academ.o Senese

- Subjects

- Festival books and prints - Italy - Padua, 1636

- Literature, Italian - Libretti - Early works to 1800

- Theatre - Stage-setting and scenery - Designers, Italian - Rivarola (Alfonso), 1607-1640

- Authors/Creators

- Obizzi, Pio Enea degli, 1592-1674

- Artists/Illustrators

- Rivarola, Alfonso, 1607-1640

- Printers/Publishers

- Frambotto, Paolo, active 1625-1664

- Owners

- Gobbis, Ludovico (Vico) de, active 1950

- Gourary, Paul, 1919-2007

- Other names

- Bartolini, Nicolò Enea, active 1638

- Erizzo, Francesco, 1566-1646

- Sances, Giovanni Felice, 1600?-1679

Obizzi, Pio Enea degli

Castello del Catajo (Padua) 1592 – 1674

L’Ermiona del S.r Marchese Pio Enea Obizzi. Per introduzione d’vn Torneo à piedi, & à cauallo e d’vn Balletto rappresentato in Musica nella Citta di Padoua l’Anno mdcxxxvi dedicata al Sereniss.o Prencipe di Venetia Francesco Erizo descritta dal S. Nicolò Enea Bartolini, Gentilhuomo, & Academ.o Senese.

Padua, Paolo Frambotto, 1638

folio (270 × 175 mm), (60) ff. signed +4 (engraved title printed from two matrices; publisher’s dedication Al Serenissimo Prencipe di Venezia; address Al Lettore with cast list Attori on verso; blank) A–O4 (description of the action and libretto) and paginated (8) 1–112; plus fifteen unnumbered folding engraved plates (see below).

Bound in the copy and not normally present are three printed scenari: ‘Argomento del primo Festino’ (at p.10); ‘…secondo Festino’ (p.42); ‘…terzo Festino’ (p.64).

Apart from these minor defects to folding plates, in excellent state of preservation: plate [2] closed tear; [3] one closed and one open tear; [6] open tear.

provenance Davis & Orioli, Catalogue 134: Rare books (London 1949), item 61 — Ludovico (Vico) de Gobbis, his woodcut exlibris with monogram vdg and motto ‘Je fus sage je fus fou’1 — with Carlo Alberto Chiesa, bookseller of Milan — Paul Gourary (1919–2007), exlibris — sale by Christie’s, ‘Splendid Ceremonies: The Paul and Marianne Gourary Collection of Illustrated Fête Books’, New York, 12 June 2009, lot 323

bound contemporary vellum-backed boards.

The illustrated libretto of an opera performed in Padua on 11 April 1636 by a travelling company of ‘mercenarii musici’, as the prelude to a tournament in the Cavallerizza di Prato della Valle of which Obizzi was the promoter.2 A prose description of the horse ballet and tournament by Nicolò Enea Bartolini is interspersed throughout Obizzi’s verse libretto; the music, by Giovanni Felice Sances, was not printed.

Unlike previous operas, L’Ermiona was not commissioned to celebrate a special occasion, nor was it performed before an audience exclusively made-up of the nobility. The architect and stage designer Alfonso Rivarola (called ‘Il Chenda’, 1591 or 1607–1640) set up a temporary wooden theatre with five vertical tiers of separated boxes accessed from the rear by corridors and common staircases. The tiers functioned as class divisions: common citizens occupied the highest and most distant tier, the principal gentlemen and women of Padua and Venice the lowest; students and foreign nobility were sandwiched between. According to Bartolini’s description (pp.6–8), spectators were assigned a time to enter the level of the box they occupied, and a new type of mixed audience was thus accommodated while preserving social hierarchies. It is the first major Italian box theatre on record and had immediate influence, guiding the design of the new Teatro San Cassiano, the first public opera stage in Venice,3 where a year later the modern tradition of commercial opera was inaugurated.4

The unsigned engravings reproduce Chenda’s settings and stage machinery.5 The first folding plate (bound at p.11) is printed from two matrices, one (275 × 400 mm) showing the proscenium and the illustrated stage curtain, the other (55 × 50 mm, irregular) positioned above the arch and displaying the insignia of the dedicatee, Francesco Erizzo, doge of Venice (1566–1646). The fourteen other plates reproduce perspective scenes, each (circa 165 × 165 mm) framed by the same proscenium plate (the curtain now masked).6 Steps at the front of the stage suggest that part of the performance took place on the floor of the hall (see Fig.3).

Stage setting by Alfonso Rivarola detto il Chenda (sheet 320 × 400 mm)

Stage setting by Alfonso Rivarola detto il Chenda (sheet 320 × 400 mm)

Before the curtain was raised, a dance was performed. Bartolini describes the scene:

Along the ground of the theatre were set up two banks on which were arrayed eighty Padovan ladies of surpassing beauty and majestic manners, who, because of the excellency of their noble bearing and the luxury of their adornments, seemed to be worthy of being invited to the wedding of a goddess. To the onlookers their eyes seemed more luminous than stars when they began a stately dance to the music of violins and viols. When this was over and they had returned to their seats, the banks where they sat moved up by means of hidden wheels to a position facing the scene. Then various concerts of musical instruments made the auditorium resound. The most noble senses were so enraptured with the beautiful sight and the sound of harmony that the spectators could believe they had ascended to the skies. Then while the spectators were overwhelmed by the many delights, the music changed and the action on the stage began.7

A ballet danced by twelve ‘giovani padovani’ costumed as shepherds, accompanied by nine musicians representing the Muses, concluded the opera.

The Roman composer Giovanni Felice Sances (1600–1679) had been working in Padua since 1618, latterly under the patronage of Obizzi, to whom he dedicated in 1633 two volumes of cantatas (some accompanying texts supplied by Obizzi). Obizzi’s libretto contains the texts of four laments, two of which employ the descending tetrachord, and that of ‘Europa’ enhanced by the sound of strings. The singers were mostly Romans and included Girolamo Medici, Felicita Uga, Maddalena Manelli (wife of Francesco), Anselmo Marconi, and Monteverdi’s son, Francesco. According to the cast list, the role of Cadmus was sung by Sances himself.

(scenari for Acts ii and iii are also present)

Three scenari (half-sheets, circa 260 × 140 mm) summarising each act of the opera scene-by-scene are preserved in this and a few other copies (see Fig.4).8 It is likely that these sheets were sold at the entrance of the theatre in 1636, were retained by some spectators, and bound by them in the libretto when it was published two years later.

The final leaf O4 is recorded in two states, the first without and the second with errata on p.112.

These copies are known to the writer

• Cambridge, ma, Harvard University, Houghton Library, *IC6 Ob350 638e (first issue, without errata) • Cambridge, ma, Harvard University, Houghton Library, Harvard Theatre Collection, ts 580.168 (second issue, with errata) • Florence, Biblioteca nazionale centrale, magl .9.4.63 • London, British Library, 639.k.5 (first issue, without errata)9 • Madrid, Biblioteca nacional, R/35564 • Milan, Biblioteca nazionale Braidense, Racc. Dramm. 5994 (‘13 c. di Tav.’) • New Haven, Yale University, Beinecke Library, Italian Festivals +43 (second issue, with errata)10 • New York, Hispanic Society of America11 • New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1955 (55.515.4) • New York, New York Public Library, Spencer Collection 163812 • New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, 07740413 • Padua, Biblioteca civica, BP.769 • Padua, Biblioteca universitaria, 36.c.3614 • Paris, Bibliothèque-Musée de l’Opéra National de Paris – Garnier15 • Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Fonds Rondel16 • Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Yd–24 (second issue, with errata) • Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Yd–1477 (‘sans les pl.’) • Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Dép. des Estampes (‘12 pl. et titre gr.’) • Rome, Biblioteca musicale governativa del Conservatorio di musica S. Cecilia17 • Rome, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Vittorio Emanuele II, 35. 5.F.1.1 • Toronto, University, Fisher Rare Book Library, 77779418 • Uppsala, National Library of Sweden, rar :137 G d Ermiona • Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, dramm. 0005. 003 • Venice, Biblioteca del Conservatorio statale di musica Benedetto Marcello, Torrefranca • Venice, Biblioteche della Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Rolandi, Grande Formato • Vicenza, Biblioteca civica Bertoliana, B 008 012 006 • Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, +35.C.38 (Mus. S)19 • Washington, Folger Shakespeare Library20 • Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, A: 298.1 Hist. 2 ̊

references Leone Allacci, Drammaturgia di Lione Allacci: accresciuta e continuata fino all’anno mdcclv (Venice 1755), col. 304; Staatliche Kunstbibliothek, Katalog der Ornamentstichsammlung der Staatlichen Kunstbibliothek, Berlin (Berlin 1939), no. 4115 (destroyed 1939–1945); Cesare Molinari, Le nozze degli dèi: Un saggio sul grande spettacolo italiano nel Seicento (Rome 1968), p.91 and figs. 47–61; Claudio Sartori, I libretti italiani a stampa, dalle origini a 1800: catalogo (Cuneo 1991), iii, no. 9160

1. Exlibris (91 × 80 mm), designed and cut circa 1948–1955 by Alberto Zanverdiani (1894–1977).

2. On Obizzi’s activities as a promoter of spectacles, see Claudia Di Luca, ‘Tra “sperimentazione” e “professionismo” teatrale: Pio Enea ii Obizzi e lo spettacolo nel Seicento’ in Teatro e Storia 11 (1991), pp.257–303; and her ‘Pio Enea 2. Obizzi promotore di spettacoli musicali fra Padova e Ferrara’ in Seicento inesplorato: l’evento musicale tra prassi e stile: un modello di interdipendenza (Como 1993), pp.499–508. Antonella Pietrogrande, ‘I tornei padovani di Pio Enea degli Obizzi’ in Il gran teatro del barocco, 1. Le capitali della festa, 1,1. Italia settentrionale, edited by Marcello Fagiolo (Rome 2007) pp.329–330 and fig. 1 (title-page).

3. Per Bjurström, Giacomo Torelli and Baroque Stage Design (Stockholm 1961), pp.34–36, 38–39; Irving Lavin, ‘On the Unity of the Arts and the Early Baroque Opera House’ in ‘All the world’s a stage–’: Art and pageantry in the Renaissance and Baroque, Part 2: Theatrical spectacle and spectacular theatre, edited by Barbara Wisch and Susan Scott Munshower (University Park, pa 1990), pp.519–579 (especially p.552 notes 40–41).

4. L’Ermiona is generally regarded as the decisive antecedent of the commercial Venetian opera; see Pierluigi Petrobelli, ‘L’Ermiona di Pio degli Obizzi ed i primi spettacoli d’opera veneziani’ in Quaderni della Rassegna musicale 3 (1965), pp.125–141; Ellen Rosand, Opera in Seventeenth-century Venice: The creation of a genre (Berkeley 1991), pp.69–72; and Franco Piperno, ‘Opera production to 1780’ in Opera production and its resources, edited by Lorenzo Bianconi and Giorgio Pestelli (Chicago 1998), pp.7–9. Francesca Gualandri, ‘Spettacoli, luoghi e interpreti a Venezia all’epoca della Didone’ in La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2005–2006, no. 7, pp.45–48, speculates that Chenda’s sets were transferred from Padua to Venice where they were reused for various productions.

5. For this scenery, and especially the symbolic representations of Venice, see Anna Laura Bellina, ‘L’armonia del buon governi. Un’immagine di Venezia nel dramma per musica del primo ’600’ in Letteratura italiana e arti figurative, edited by Antonio Franceschetti (Florence 1988), ii, pp.685–690.

6. The first act, ‘Il Rapimento d’Europa’, in ten scenes, is illustrated by three plates, bound respectively after p.16 (scene 2), p.30 (scene 5), and p.39 (scene 8); the second act, ‘Gli Errori di Cadmo’, in five scenes, by two plates, at p.53 (scene 4) and p.55 (scene 5); and the third act, ‘Gl’ Imenei’, in thirteen scenes, by nine plates, at p.65 (scene 1), p.69 (scene 2), p.76 (scene 4), p.85 (scene 5), p.88 (scene 6), p.92 (scene 7), p.98 (scene 8), p.99 (scene 9), p.105 (scene 10). According to Bartolini (p.65), the libretto of the third act was written by ‘Sig. Abbate Tonti’.

7. Bartolini, p.8; translation by George R. Kernodle, ‘General Introduction: The Renaissance Stage’ in The Renaissance Stage: Documents of Serlio, Sabbattini and Furttenbach, edited by Barnard Hewitt (Coral Cables, fl 1958), pp.3–4.

8. Libreria Vinciana, Autori italiani del ‘600, compiled by Sandro Piantanida, Lamberto Diotallevi, and Giancarlo Livraghi (Milan 1948), no. 226 (inserted at pp.10, 42, 54).

9. Dennis E. Rhodes, Catalogue of seventeenth century Italian books in the British Library (London 1986), p.624.

10. Ex-libris Bruno Brunelli Bonetti. View a digital version in the Beinecke Library’s Digital Images Online database (link).

11. Clara Louisa Penney, Printed books 1468–1700 in the Hispanic Society of America (New York 1965), p.390.

12. Ex-libris Giacomo Soranzo (1742) — E.F.D. Ruggieri (sale 1873, lot 799). ‘The plate facing p.89 is a duplicate of that facing p.16, with a different scene mounted over the original one within the border.’

13. Donald M. Oenslager (1902–1975); Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager, 1981.

14. Maria Ida Biggi, in Le muse tra i libri: il libro illustrato veneto del Cinque e Seicento nelle collezioni della Biblioteca universitaria di Padova, catalogue of an exhibition held at Palazzo Zuckermann, Padua, 11 September–18 October 2009, edited by Pietro Gnan and Vincenzo Mancini (Padua 2009), pp.142–143 no. 28 (plate for Act iii, scene 5 reproduced).

15. Located by Suzanne P. Michel, Répertoire des ouvrages imprimés en langue italienne au xviie siècle conservés dans les bibliothèques de France (Paris 1976), vi, p.30 (also locating copies in the Arsenal and Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

16. Ex-libris Edward Gordon Craig. Bibliothèque nationale (France), Enrichissements de la Bibliothèque nationale de 1945 à 1960: dons et acquisitions (Paris 1960), p.212 no. 1224 (acquired 1957).

17. Exhibited Illusione e pratica teatrale: proposte per una lettura dello spazio scenico dagli Intermedi fiorentini all’opera comica veneziana, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, edited by Franco Mancini, Maria Teresa Muraro, Elena Povoledo ([Vicenza] 1975), p.61 no. 17.

18. Beatrice Corrigan, Catalogue of Italian Plays, 1500–1700, in the Library of the University of Toronto (Toronto 1961), p.68.

19. Europäische Theaterausstellung, Wien, Künstlerhaus, 20. September–5. Dezember 1955, catalogue of an exhibition by Franz Hadamowsky and Heinz Kindermann (Vienna [1955]), p.67 no. 11.

20. Louise George Clubb, Italian plays (1500–1700) in the Folger Library: a bibliography with introduction (Florence 1968), pp.170–171 no. 634 and fig 11.