Monumenta sepulcrorum cum epigraphis ingenio et doctrina excellentium virorum: aliorumque tam prisci quam nostri seculi memorabilium hominum: de archetypis expressa

- Subjects

- Archaeology, Greek & Roman - Early works to 1800

- Art books - Early works to 1800

- Book illustration - Artists, German - Fendt (Tobias), c. 1520/1530-1576

- Epigraphs - Early works to 1800

- Authors/Creators

- Fendt, Tobias, c. 1520/1530-1576

- Artists/Illustrators

- Fendt, Tobias, c. 1520/1530-1576

- Printers/Publishers

- Scharffenberg, Crispin, died 1576

- Owners

- Froben, Johannes, of Neisse, active 1574

- Fürstlich Fürstenbergische Hofbibliothek (Donaueschingen)

- Schmid, Peter, of Coberg, active 1574

- Other names

- Ribisch, Siegfried, 1530-1584

Fendt, Tobias

Antwerp c. 1520/1530 – 1576 Breslau (Wroclaw)

Monumenta sepulcrorum cum epigraphis ingenio et doctrina excellentium virorum: aliorumque tam prisci quam nostri seculi memorabilium hominum: de archetypis expressa.

Breslau (Wroclaw), Crispin Scharffenberg, 1574

folio (313 × 210 mm), (6) ff. signed A6 including engraved title and letterpress ‘Praefatio’, plus 129 etched plates by Fendt numbered 1–3, 3*, 4–13, 13*, 14–21, 21*, 22, 22*, 23–125.

provenance inscription on the front free-endpaper, dated April 1594, recording the gift of the book by Johannes Froben of Neisse to Peter Schmid of Coberg, the local representative of archduke Ferdinand ii of Austria — Fürstlich-Fürstenbergische Bibliothek at Donaueschingen, lettered ink stamp in a corner of the title-print — Reiss & Sohn, ‘Auktion 68: Aus einer Süddeutschen Fürstenbibliothek, Teil 1’, Königstein im Taunus, 20 October 1999, lot 60

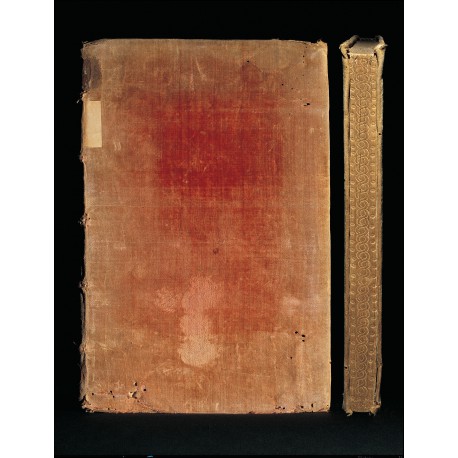

Short wormtracks along the upper edge of the engraved title, pin wormholes in blank margins at end, otherwise in fine state of preservation. The fabric across the back of the binding has lost its pile; general fading and soiling, some worming, edges and corners abraded.

binding contemporary rose-coloured velvet over paper boards, back divided into six compartments by raised bands; gilt gauffered page edges.

First edition of a suite of prints reproducing a sylloge of inscriptions and monumenta sepulchralia, compiled by a Silesian nobleman, Siegfried Ribisch (1530–1584), during his ten-year peregrinatio academica across Europe (1545–1554).1

A younger son of the imperial councillor in Breslau, Heinrich Ribisch (1485–1544),2 Siegfried was sent to study aged fifteen in Strasbourg. After his father’s death, he commenced protracted travels and studies, matriculating at Orléans, Poitiers, Bologna (1554),3 and probably Padua. He maintained throughout a diary or ‘Itinerarium’ in which the monuments he saw were recorded (although the manuscript is autograph, the drawings possibly were contributed by others).4 Upon his return home, Rybisch was appointed Kammerrat in service of Maximilian ii at Pressburg, and subsequently for Rudolph ii in his native Breslau. He both conducted and sponsored scholarship, becoming the ‘Vater der schlesischen Altertumskunde und Geschichtsschreibung’.5

The painter and engraver Tobias Fendt was already active in Breslau by 1565, when he painted ‘Ezechiel’s Vision’ (epitaph of Magdalen Mettel, now in Muzeum Narodowe, Wrocław). At some point Ribisch entrusted his ‘Itinerarium’ to Fendt, who proceeded to etch about 150 inscriptions and monuments. ‘Certaines planches correspondent aux relevés du manuscrit, d’autres donnent des textes d’épitaphes auxquelles le manuscrit se contentait de faire allusion, d’autres enfin, comme celle de Reuchlin, n’ont pas été signalées dans le manuscrit’.6

The plates are arranged by subject, commencing with epitaphs of classical writers (from Naevius to Papinian, including Virgil’s tomb at Posilippo, then Northern humanists and reformers (including Celtes, Erasmus, Oecolampadius, Melanchthon, and Reuchlin), Petrarca, Dante, and Italian humanists (including Politian, Valla, Bessarion, Ficino, Poggio Bracciolini, and Pico della Mirandola), inscriptions in Pontano’s tempietto at Naples, monuments of Bolognese lawyers and humanists, and non-monumental classical (or pseudo-classical) inscriptions, mostly transcribed from the original stones in Rome.7

(reduced from 282 × 175 mm, platemark)

It is an extraordinary blend of the reliable and the fantastic: the sepulchral monuments in the Bolognese church of S. Domenico are copied faithfully and provide a veritable tour of that church;8 yet all fifteen of the ‘ancient’ epitaphs are falsae (tributes rather than deceptions) or wrongly attributed. These include a fake inscription for Ovid and – bizarrely – a Latin epitaph for Euripides.9

The work was extremely well-received and the matrices were re-struck at Breslau in 1584, again at Frankfurt am Main in 1585 and 1589 (in these editions, the plates are extensively reworked, and a new title-print designed by Jost Amman introduced by the publisher, Sigmund Feyerabend), yet again at Amsterdam in 1638 and at Utrecht in 1671 (in these editions, elogia collected by Marcus Zuerius Boxhorn are printed facing the plates, now reduced to 125 in number).

This is a remarkable and highly desirable copy: fabric bindings of the sixteenth century are now seldom encountered on the market.

references Andreas Andresen, Der Deutsche Peintre-Graveur (Leipzig 1872), ii, pp.32–49; Désiré Guilmard, Les Maîtres ornemanistes (Paris 1880), p.372 no. 46; Katalog der Ornamentstichsammlung der Staatlichen Kunstbibliothek Berlin (1939), no. 3673; Marta Burbianka, Produkcja typograficzna Scharffenbergów we Wrocławiu (Wrocław 1968), no. 171; F.W.H. Hollstein, German etchings, engravings & woodcuts, 1400–1700 (Amsterdam 1968), viii, p.37; Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachbereich erschienenen Drucke des xvi. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart 1986), F–727

1. Jean Hiernard, ‘Un étudiant silésien à Poitiers, Seyfried Ribisch’ in Bulletin de la Société des antiquaires de l’Ouest et des musées de Poitiers, fifth series, 13 (1999), pp.27–68; Claudia Zonta, Schlesische Studenten an italienischen Universitäten. Eine prosopographische Studie zur frühneuzeitlichen Bildungsgeschichte (Stuttgart 2004), p.373 no. 1206.

2. Richard Förster, ‘Heinrich und Seyfried Ribisch’ in Zeitschrift des Vereins für Geschichte Schlesiens 41 (1907), pp.180–240.

3. Gustav C. Knod, Deutsche Studenten in Bologna (1289–1562) (Berlin 1899), p.449 no. 3042.

4. Rybisch’s ‘Itinerarium’ (146 ff.), formerly in the Stadtbibliothek Breslau, is now Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej we Wrocławiu, M 1375; see Hiernard, op. cit., p.32. Apparent copies of Rybisch’s sylloge are Graz, Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv, Sign. 205 (Getrud Schomandl, ‘Der sogenannte Boissard-codex im Steiermärkischen Landesmuseum mit den Originalzeichnungen von Tobias Fendt’, dissertation, Universität Graz, 1946; cf. Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon, 38, Munich & Leipzig 2003, p.149); Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Collections Jacques Doucet, MS 618 / BAA 303 a 17.

5. Förster, op. cit., p.227; Oskar Pusch, Die Breslauer Rats- und Stadtgeschlechter in der Zeit von 1241 bis 1741 (Dortmund 1986–1991), iii, p.421.

6. Hiernard, op. cit., p.61; Sergiusz Michalski, ‘Seyfrieda Rybischa i Tobiasza Fendta Monumenta Sepulcrorum cum epigraphis’ in O ikonografii swieckiej doby humanizmu, edited by Jan Bialostocki (Warsaw 1977), pp.77–158, reproducing twenty-one etchings opposite seventeen photographs of monuments.

7. John Sparrow, Visible words: a study of inscriptions in and as books and works of art (Cambridge 1969), pp.28–30.

8. Yoni Asher, ‘Giovanni Zacchi and the tomb of Bishop Zanetti in Bologna’ in Source 12 (1993), pp.24–29.

9. Joseph B. Trapp, ’Ovid’s tomb’ in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 36 (1973), pp.51–52; J.B. Trapp, ‘The Grave of Vergil’ in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 47 (1984), pp.15–16.