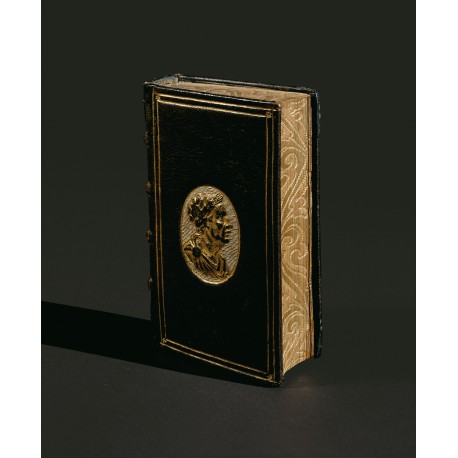

Superbly preserved plaquette binding for Marcus III Fugger (1529-1597)

De vita libri tres, recens iam a mendis situq[ue] vindicati, ac summa castigati diligentia, quorum primus, De studiosorum sanitate tuenda. Secundus, De vita producenda. Tertius, De vita coelitus comparanda

- Subjects

- Bookbindings, Medallion or plaquette

- Medical books - Early works to 1800

- Authors/Creators

- Ficino, Marsilio, 1433-1499

- Printers/Publishers

- Rouillé, Guillaume, active 1546-1588

- Owners

- Fugger, Marcus, 1529-1597

- Fürstlich Oettingen-Wallerstein'sche Bibliothek (Harburg)

Some of the finest and most distinctive works of applied art of the Italian Renaissance are its bindings decorated with medals or plaquettes. Like the columns and broken arches in the background of Mantegna’s paintings they express the passionate interest of contemporary scholars in the visible relics of antiquity. Although they enjoyed a long vogue, they can never have been common. Only about 470 examples have come to light and more than half of these were made for one or another of four collectors. Specimens are known from many different shops, but only a handful of craftsmen seem to have had the skill, or perhaps the patience, to succeed consistently in obtaining good results. No doubt their charges were higher than for ordinary work, and the extra expense was more than most book-buyers chose to incur. Plaquette bindings were thus normally reserved for special copies or special clients. The cost however was not the only consideration; philosophic issues were also at stake. To begin with, at least, ornament of this sort denoted an author’s or an owner’s faithfulness to the spirit of the antique world.’1

Anthony Hobson

Ficino, Marsilio

Figline (Florence) 1433 – 1499 Careggi (Florence)

De vita libri tres, recens iam a mendis situq[ue] vindicati, ac summa castigati diligentia, quorum primus, De studiosorum sanitate tuenda. Secundus, De vita producenda. Tertius, De vita coelitus comparanda.

Lyon, Guillaume Rouillé, 1560

sextodecimo (120 × 72 mm), (232) ff., signed a–z8 A–F8 (blank F8) and paginated 1–461 (3). Printer’s device on title-page.

provenance Marcus Fugger (1529–1597) — Fugger library shelfmark (or inventory note) in brown ink on front pastedown, An 195 Nro 547 —Bibliothek der Fürsten von Oettingen-Wallerstein, Maihingen, heraldic black inkstamp lettered Oetting. Wallerstein on title-page — Karl & Faber, ‘Auktion xi: Bibliophile Kostbarkeiten der Fürstl. Öttingen-Wallerstein’schen Bibliothek in Maihingen (dabei “Marcus Fugger” Teil iv)’, Munich, 7 May 1935, lot 204 — Librairie Lardanchet, ‘Catalogue 45: Beaux Livres Anciens et Modernes’, Paris, 1951, item 1022 (reproduced) — Pierre Berès, ‘Catalogue 93: Livres rares. Six siècles de reliures’, Paris, 2004, item 25

Insignificant repair to upper joint, otherwise in faultless state of preservation.

binding contemporary olive-brown morocco over paper boards; on both covers in high relief a gilt oval medallion head of Julius Caesar laureate, draped bust to right, tunic clasped on right shoulder, hatched ground (44 × 33 mm), covers framed by two gilt rules, single impressions of a gilt eight-pointed star tool in angles between rules; the back divided into seven compartments by four real and two false bands each articulated by three or two gilt rules respectively, within six compartments an impression of a gilt four-petal flower tool; page-edges gauffered and parcel-gilt. Contained in a box.

This beautiful and exceptionally well-preserved binding featuring a medallion portrait of Julius Caesar modelled in high relief is one of a small group of seven books acquired by the celebrated patron and connoisseur of luxury bookbindings, Marcus iii Fugger, in Lyon or Geneva, in the 1560s.2 Two other books of this group are decorated by the same plaquette;3 the others are decorated by well-cut medallion heads of Nero, a young man, a male mask, and Judith.4 All seven books were printed in small format in Lyon between 1552 and 1560. They are evidence of the fashion for medallion bindings which developed in Northern Europe during the 1550s, just as the taste for them was waning in Italy.

Plaquette ornament on bindings had been conceived by the Paduan antiquaries in the mid-1460s, as a style of binding appropriate for humanistic works. The models were Roman imperial coins, antique intaglios, Renaissance and later medals, and the decoration was achieved by impressing the covers with an intaglio stamp, leaving an impression in relief. At first their use was reserved for presentation or other special copies, but by the second quarter of the sixteenth century their commercial use became more frequent. Bindings decorated by plaquettes of Julius Caesar were among the most popular in Italy: twenty-one examples are known, produced in at least five towns, covering books printed between circa 1477 and 1558. The prototype was an antique intaglio in the Medici collection (Hobson 1989 no.15); a concave plaquette which may have been used by the binders has survived.5

The metallic prototype for the plaquette adorning this binding is not yet identified. Hobson draws attention to ‘a somewhat similar plaquette’, a silhouetted lead bust, attributed to a Nuremberg Master of the second third of the sixteenth century, which Ingrid Weber publishes from the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich.6 This lead is significantly smaller (height 31 mm versus 44 mm) and is of different design and proportions; moreover, the head has a schematic character, whereas the plaquette on our binding is based on a more classically accurate profile. The overall impression of the plaquette on our binding suggests a Mediterranean (Italian, or possibly French prototype), rather than Transalpine design.7

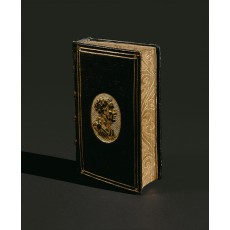

The plaquette of Julius Caesar on the covers of Fugger’s Cicero (British Library) is enclosed by a frame of two gilt rules, with a star in the angles between the rules, just as on our binding (see Fig. 3). The plaquette of Nero on the covers of Fugger’s Actuarius (British Library) is ornamented in each angle by gilt impressions from an azured fleuron tool employed on neither the Cicero nor our binding.8 There are remarkable coincidences in structure and forwarding, however, and it is likely that the three volumes were bound in the same shop.9

Comparative illustration

Fig.3 Marcus Fugger’s Cicero (Lyon 1552–1554)

(British Library, Henry Davis Gift 422; 122 × 72 × 51 mm)

A copy of Martial’s Epigrammata (Lyon: Sebastian Gryphius, 1553), apparently decorated with the same ‘late, northern version of the plaquette of Julius Caesar laureate’ as our Ficino and the British Library’s Cicero, but not associated with Marcus iii Fugger, is also known.10 According to Hobson, it is ‘probably Lyonese or, less probably, Genevan’.11

Another binding, covering Christophe de Roffignac’s De re sacerdotali, seu pontificia, quatuor libris exarata commentatio, printed in octavo format in Paris by Poncet Le Preux, in 1557, is decorated by a similar medallion portrait of Julius Caesar.12 Although the plaquettes on the covers of the Roffignac and Ficino may depend from the same prototype, they were produced by intaglio stamps of quite different shape and detail: the volumes of space behind Julius Caesar’s head are inequal, and the background is stippled on the Roffignac and hatched with parallel lines on the Ficino and Cicero.

reference Henri Louis Baudrier, Bibliographie lyonnaise: recherches sur les imprimeurs, libraires, relieurs et fondeurs de lettres de Lyon au xvie siècle (reprint Paris 1964), ix, p.272

1. Anthony Hobson, Humanists and Bookbinders: the Origins and Diffusion of the Humanistic Bookbinding 1459–1559, with a census of historiated plaquette and medallion bindings of the Renaissance (Cambridge 1989), p.94.

2. The copy is cited by Hobson, op. cit., 1989, no. 134b.

3. (1) Cicero, Les oeuvres (Lyon: Guillaume Rouillé, 1552) bound with Cicero, Les Epistres familiaires (Lyon: Guillaume Rouillé, 1554), in sextodecimo format (British Library, Henry Davis Gift 422). For reproduction, see the British Library’s ‘Database of Bookbindings’, Davis 422 (link). Hobson, op. cit., 1989, p.142 note 62; Mirjam M. Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: a collection of bookbindings. Volume iii: A Catalogue of South-European Bindings (New Castle, de & London 2010), pp.277–278 no. 224. (2) Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (Lyon: Jean de Tournes, 1552), in sextodecimo format, three volumes bound in two (location unknown). Hobson, op. cit., 1989, no. 134a. Like our volume, these two books were in the Oettingen-Wallerstein sales of 1933–1935 (6 November 1933, lots 163 and 452 respectively).

4. Nero: Joannes Actuarius, Opera (Lyon: Jean de Tournes & Guillaume Gazeau, 1556), in sextodecimo format, three volumes bound in one (British Library, Henry Davis Gift 590). Oettingen-Wallerstein sale, 11 May 1934, lot 223; Hobson, op. cit., 1989, no. 133a; Foot, op. cit., 2010, no. 225. For a reproduction, see the British Library’s ‘Database of Bookbinding’, Davis590 (link). Young man: Ammianus Marcellinus, Rerum gestarum libri decem et octo (Lyon: Sebastian Gryphius, 1552), in sextodecimo format (Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg, ii.5.8°.6). Hobson, op. cit., 1989, no. 141a, fig. 190. Male mask: Berosus, De antiquitate Italiae (Lyon: Barthélemy Frein for Jean Temporal, 1554), in sextodecimo format (Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg, iv.12.8°.130). Hobson, op. cit., 1989, no. 142a, fig. 191. Judith: Le Nouueau Testament de Nostre Seigneur Iesus Christ (Lyon: Guillaume Rouillé, 1554), in sextodecimo format (Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg, xiii.1.8°.99). Hobson, op. cit., 1989, no. 143a, fig. 192. The latter three books entered the Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg in 1980.

5. Giuseppe Toderi and Fiorenza Vannel Toderi, Placchette secoli xv–xviii nel Museo Nazionale del Bargello (Florence 1996), no. 30.

6. Ingrid Weber, Deutsche, Niederländische und Französische Renaissanceplaketten (Munich 1975), no. 108/1, Tafel 38.

7. We are guided to this conclusion by Dr. Doug Lewis, Emeritus Curator of Sculpture and Decorative Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington, dc (private communications).

8. See above (note 4); and Foot, The Henry Davis Gift: a collection of bookbindings. Volume i: Studies in the history of bookbindings (London 1978), pp.212, 215 note 53; M. Foot, op. cit., 2010, p.279 no. 225, associating this hatched, three-leaf fleuron tool with the ‘Goldast Binder. Cf. Hobson, op. cit., 1989, p.142, note 62, and Hobson’s reproduction of Fugger’s Ammianus Marcellinus fig. 190.

9. See Foot, op. cit., 2010, pp.277–279. All three books are sewn on four supports, showing on the spine as four real and two false bands; all three have the same (or very similar) four-petal flower tool decorating the spine; the headbands of the Ficino and Actuarius are blue and gold threads (pink thread is used for the Cicero); a blind fillet decorates the turn-ins; and the page-edges are similarly gauffered and parcel-gilt. In our Ficino, the binder has inserted at front and back of the volume eight blank leaves (one leaf of each quire pasted to inner cover); in the Cicero and Actuarius, there are also multiple blank leaves (more are laid to the pastedowns).

10. This volume was in the library of Théophile Belin and was sold by Laure Belin in 1936 (Louis Giraud-Badin and Charles Bosse, ‘Bibliothèque de Mme Th. Belin: Précieux manuscrits à miniatures, livres à figures des xvie, xviie et xviiie siècles, riches reliures anciennes armoriées’, Paris, 19 February 1936, lot 93, the portrait of Julius Caesar mistaken for the poet Martial); in 2001, it reappeared on the market in a catalogue of Librairie Alix, ‘Livres anciens’, Verrue (France), item 48.

11. Anthony Hobson, ‘Three plaquette bindings and a German collector’ in Bibliophiles et reliures: mélanges offerts à Michel Wittock, edited by Annie De Coster, Claude Sorgeloos, and Marcus de Schepper (Brussels 2006), p.266 (not reproduced).

12. Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, A: 57.13 Theol.; inside is the ownership entry of one Georg Wagner, dated 29 May 1586. See Anthony Hobson, ‘Plaquette and medallion bindings: a second supplement’ in For the love of the binding: Studies in bookbinding history presented to Mirjam Foot (London 2000), pp.67–79, no. 134ax.