The Italian historian’s famous ‘History of inventions and discoveries’, the fine Fugger copy of the second, revised edition

Adagiorum liber. Eiusdem de inuentoribus rerum libri octo, ex accurata autoris castigatione, locupletationéq. non uulgari, adeo ut maxima ferè pars primae ante hanc utriusq. uoluminis aeditioni accesserit

- Subjects

- Science books - Inventions and discoveries - Early works to 1800

- Authors/Creators

- Vergilius, Polydorus, 1470?-1555

- Artists/Illustrators

- Graf, Urs, 1485?-1527?

- Printers/Publishers

- Froben, Johann, active 1491-1527

- Owners

- Fugger, Marcus, 1529-1597

- Fürstlich Oettingen-Wallerstein'sche Bibliothek (Harburg)

Vergilius, Polydorus

Urbino 1470? – 1555 Urbino

Adagiorum liber. Eiusdem de inuentoribus rerum libri octo, ex accurata autoris castigatione, locupletationéq. non uulgari, adeo ut maxima ferè pars primae ante hanc utriusq. uoluminis aeditioni accesserit.

Basel, Johann Froben (July 1521)

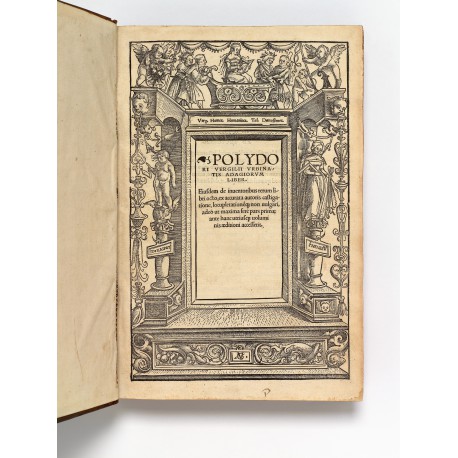

Two parts, folio (302 × 200 mm), (206) ff. signed A6 a–q6 r4, A–D6 E8 F–P6 Q8 and irregularly foliated (6) 1–114 (i.e. 100), (6) 1–92 (i.e. 94). Woodcut border on title-page, horizontal and vertical borders on first page of text, woodcut initials, and printer’s device.

provenance Marcus Fugger (1529–1597), the binding fore-edge boldly lettered in ink Pol. Verg. Adag. by a Fugger librarian, and shelfmark xxvi–a–18 written on free-endpaper — sale of the residue of the Fugger family library by Sotheby’s, ‘Fine Continental Books and Manuscripts’, London, 5 December 1991, lot 215

The spine of the binding abraded at foot, with partial loss of leather in one compartment; vellum spine labels missing; otherwise a faultless copy.

binding near-contemporary French calf; covers panelled in blind.

First printing of revised and vastly enlarged editions of Polydore’s collection of adages or proverbs and of his encyclopaedia De Inventoribus rerum, on those who have discovered things, in a well-preserved contemporary calf binding of circa 1550 executed in Paris for Marcus (Marx) Fugger. The edition is distinguished by a fine woodcut title-border representing the ‘Triumph of Humanitas’ by Urs Graf (see Fig.1).1

The Adagia or Proverbiorum libellus was originally published at Venice in 1498 as a collection of 306 proverbs drawn exclusively from classical sources. In the dedicatory letter to Richard Pace written for our Basel edition, the author explains that he began to collect adagia sacra because he felt that Christians should not depend on Greek and Latin proverbs alone, but should season their writings also with Christian wisdom. These adagia sacra, taken from the Bible and the Gospels in particular, are 431 in number, and practically double the size of the work.

Polydore’s De Inventoribus rerum, an encyclopaedia of inventors and inventions mainly from the classical past, but also Jews, Egyptians, and Asiatics, was first printed at Venice in 1499, as three books dealing with material inventions, natural philosophy, medicine, and other profane matters. In our 1521 edition, Polydore introduced five new books on the history, organisation, and rituals of the church, including much information on pagan customs, which ensured that the book was placed on the Index (first by the Sorbonne in 1551, then on the Trent Index in 1564). The work is celebrated as the earliest history of medicine after the invention of printing, as the first modern effort to explore the history of technology, and as an early and original essay in anthropology and comparative religion. Also considered are painting and painters (notably Raphael), sculpture, and architecture in the author’s native Italy.2 Thirty Latin editions had appeared by Polydore’s death in 1555 and in all more than one hundred editions in various recensions and seven languages were published by the eighteenth century.3

The binding belongs to a group of similarly bound volumes that once formed a substantial part of Marcus Fugger’s library. The material of these tasteful bindings is a smooth brown calf decorated by one, two, or three panels (see Fig.2), each formed by three fillets, with a fleur-de-lys stamped at the angles in gilt or blind (as here). The centres of the covers sometimes are left empty (as here), or are decorated by an emblematic bird tool or double-headed eagle.4 The volumes of this group were all bound circa 1545–1552 in the same anonymous (probably Parisian) workshop, which apparently also executed luxurious bindings for Fugger.5

Most of Fugger’s books have the author’s name (and/or title) boldly lettered in ink up the fore-edge, indicating how the books originally stood on the shelves in his library. At an uncertain, later date, the volumes were shelved in the modern manner, and a librarian pasted vellum labels descriptive of the contents onto the spines (as often, the label has fallen away from our volume, leaving a residue of the adhesive).6

A large part (if not all) of Marcus Fugger’s books descended to the princes of Oettingen-Wallerstein; the finest were sold in Munich by Karl & Faber in 1933–1934. Many others, incorporated in the Oettingen-Wallerstein family library at Schloss Harburg (formerly Maihingen), were sold in 1980 to Freistaat Bayern and deposited in Augsburg University Library. The remnants, including the present volume, were consigned anonymously to Sotheby’s, and sold on 5 December 1991.

references H.M. Adams, Catalogue of books printed on the continent of Europe, 1501–1600, in Cambridge libraries (Cambridge 1967), V–442; Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachbereich erschienenen Drucke des xvi. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart 1994), V–772

1. F.W.H. Hollstein, German etchings, engravings & woodcuts, 1400–1700 (Amsterdam 1977), xi, p.138; Frank Hieronymus, Oberrheinische Buchillustration, 2: Basler Buchillustration 1500–1545, catalogue of an exhibition held in Universitätsbibliothek Basel (Basel 1984), pp.120–121, fig. 176.

2. Brian P. Copenhaver, ‘The historiography of discovery in the Renaissance: the sources and composition of Polydore Vergil’s De Inventoribus rerum’ in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 41 (1978), pp.192–214; Catherine Atkinson, Inventing inventors in Renaissance Europe: Polydore Vergil’s ‘De inventoribus rerum’ (1499 and 1521) (Tübingen 2007), p.98.

3. Helmut Zedelmaier, ‘Karriere eines Buches: Polydorus Vergilius De inventoribus rerum’ in Sammeln, Ordnen, Veranschaulichen: Wissenskompilatorik in der Frühen Neuzeit (Münster 2003), pp.175–203 (esp. p.190); details of eighty-four 16th and 17th century editions, with locations of 479 copies (including fifteen of our 1521 Basel edition), are provided on Zedelmaier’s online project (http://dbs.hab.de/Polydorusvergilius/portal-texte/text_01_e.htm; link).

4. Ilse Schunke, ‘Der Pariser Marx-Fugger Meister’ in Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 1952, pp.189–194; Anthony Hobson and Paul Culot, Italian and French 16th-century bookbindings (revised edition Brussels 1991), pp.100–103 no. 41; Michael Laird, ‘Some sixteenth-century bindings in the New York Public Library’ in Bulletin du Bibliophile 1994, pp.308–311.

5. Paul Needham, Twelve Centuries of Bookbinding 400–1600 (New York 1979), pp.204–205; Paul Rupp, ‘Pracheinbände Pariser Meister aus der Bibliothek des Marcus Fugger’ in Bibliotheksforum Bayern 13 (1985), pp.77–86.

6. See reproductions in Hobson and Culot, op. cit., pp.100, 103.