Lely's Library

Although the English court portraitist Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680) has long been renowned as a collector and connoisseur of old master paintings, drawings and prints,1 he is still virtually unknown as a bibliophile. A single book from Lely’s library was identified by Frederick Clarke, in 1893;2 another was reported by W.C. Hazlitt the next year;3 and subsequent literature has referred exclusively to a third volume, containing Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (1624), bound with a collected edition of Spenser’s works (1617), which disappeared from view in the 1920s.4 Its return to the market, in June 2016, with Henry Sotheran Limited, followed by the reappearance of Lely’s Lomazzo (1598), in the Foxe Pointe Library sale (Sotheby’s, New York, 26 October 2016, lot 191), provide an occasion for these notes.

An account book kept by the Executors, detailing their administration of Lely’s estate, recording debtors, proceeds from the sales of household goods, studio materials, works by Lely himself, and Lely’s art collections, is our principal source of knowledge about Lely’s possessions, since no probate inventory has survived.8 Regrettably, the Executors’ account book contains little information regarding Lely’s books and library. The earliest of the few relevant entries is a payment on 14 December 1681 ‘To Nott the bookbinder in full… 13-00-00’.9 William Nott (fl. 1660-1691), mentioned in Pepys’s diary in 1669 as ‘the famous bookbinder that bound for my Lord Chancellor [Clarendon]’s library’,10 was proprietor of a large workshop in Pall Mall, whose clientele during the 1670s included both Catherine of Braganza and Mary of Modena.11 Another entry records a payment on 25 September 1682 ‘To Mr Pitt for 2 volumnes of his Atlas according to Sr Peter’s subscription and binding… 06-10-00’.12 Moses Pitt (c. 1639-1697) was a bookseller and printer, whose English Atlas appeared (in four volumes) at Oxford in 1680.13

These debts were among a great many that the Executors settled with proceeds from sales of furniture, china, jewellery, and other belongings removed from Lely’s house and studio, 10-11 the Great Piazza, Covent Garden.14 The contents of Lely’s studio – more than 100 paintings by Lely himself, some unfinished, together with very numerous copies – was inventoried and valued, and during April-May 1681 a former studio assistant, Frederick van Son (Sonnius), was installed in the house to receive prospective purchasers and sell the paintings at fixed prices.15 About the same time, the ‘utensils of painting’ – pigments, supports, frames, and related materials – were likewise sold.16 As the Executors ‘cleared the hous of trumpery, which was the furniture’, Lely’s principal assets – his collections of paintings, drawings and prints – remained ‘sealed up’ for safety.17

The Executors at first proposed to sell these valuable collections by lottery, then a more-established sales mechanism than public auction. By 28 November 1681, however, they had abandoned that idea, and resolved to sell Lely’s art collections by auction. On 18 April 1682, the Executors commenced a four-day sale of paintings and large-scale drawings (approximately 575 items altogether).18 Afterwards, they continued to clear the house, in anticipation of letting it. During the summer of 1682, the drawing and print collections were withdrawn for safekeeping in the house of one of Roger North’s brothers;19 the library was emptied about the same time. On 25 September 1682, the Executors made two payments: ‘To the Joyner for caseing up the Library to be carryed into the Country… 03-07-00’ and ‘For Carriage of the Library 03-10-00’.20 The amounts are conspicuous, and signify that Lely had more than the usual artist’s haphazard accumulation of volumes. Moreover, they reveal that he had a ‘Library’, a place reserved in his house for keeping books and for their study.

The destination of the library was Lely’s house at Kew, the lease of which the Executor Roger North successfully transferred (in trust) to John Lely, then a pupil of Eton College.21 A wayward youth, John took up residence in 1689, when he married, six months before his twenty-first birthday, Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Knatchbull, Bart. Widowed three years later, John married on 23 January 1693 (Old Style) Anne, daughter of Richard Mounteney of Kew,22 and it appears that he resided in the house at Kew up until his death in November 1728.23 On 31 January 1729, the auctioneer Christopher Cock (fl. 1717-1748) offered in his Soho salerooms ‘The Collection of Paintings belonging to Mr. Lely; of Kew-Green, deceased, collected by his Father, the famous Sir Peter Lely’ together with property of Henry Clinton, 7th Earl of Lincoln (died 7 September 1728). An advertisement for this sale in the Daily Post, 23 January 1729, does not mention books, nor any other chattels of John Lely; however, it does conclude ‘the House of Mr. Lely, on Kew-Green, is to be lett. Enquire of Mr. Cock’, which implies that the house had been completely cleared.24 No copy of a printed ‘catalogue’ (presumably a handbill) circulated by the auctioneer is known.

It seems that Peter Lely kept some heavily illustrated books alongside his drawings and prints, apart from the formal library. In the spring of 1686, the Executor Roger North came to dwell in Lely’s house and the drawing and print collections – removed over the summer of 1682, for safekeeping – were returned. Roger North set himself the laborious task of organising them for sale: by his account, there were ‘neer 10,000’ items. As North relates in his autobiography, he obtained ‘a stamp P.L. and with a little printing ink, I stampt every individuall paper’ and ‘digested them into books, and parcells, such as wee called portofolios’. An auction of the drawing and print collections was widely advertised in London, Holland, and Paris,25 and on 16 April 1688 the sale commenced. When, after eight days, ‘the buyers began to be clogged with the quantity, and could not well digest any more’, Roger North interrupted the sale.26 North intended to sell all remaining drawings and prints in April 1689, however ‘this wonderful Revolution came on and hindered me’.27 They eventually were offered in auction sales conducted by Parry Walton on behalf of John Lely in February and November 1694.28

Unlike the paintings sold in 1682, there is no detailed list in the Executors’ account book of drawings and prints, and few buyers in the 1688 auction sale are named. Various lists are known to have made, by several parties: North states that he ‘made lists of each book, and described every print and drawing’,29 and records of prices and buyers were kept by both Frederick van Son, who executed commission bids, and by the cashier, Thomas Mills; but none is known to survive. The Executors’ account book indicates that twenty-four ‘Portfolios’ of prints and an unspecified number of ‘Books of prints bound’ were sold in 1688, for a total of £597-18-6. Of that sum, ‘Books of prints bound’ amounted to £29-4-6.30

What were these ‘Books of prints bound’: sets of prints, bound together on their own paper, which we might recognize as books; or bound quires of blank leaves with prints attached to them, more like albums than books? Were similar items sold in 1694? There is uncertainty too about the appearance and construction of Lely’s ‘Portfolios’. Some perhaps were no more than two rigid covers, between which was placed a bundle of prints; others may have held backing sheets, either loose or in a fixed position, to which trimmed prints could have been inlaid, or pasted by their four corners.31 A number of suites of prints, each marked with the P.L monogram, exist in later bindings. Some of these sets could be Lely’s ‘Books of prints bound’, albeit in new bindings applied by their subsequent owners; others doubtless were confected by later collectors, from Lely’s dismembered portfolios.

In the University of Glasgow Library, for example, is a set of forty prints by Antonio Tempesta for Otto van Veen’s Historia septem infantium de Lara, published at Antwerp by Philip Lisaert in 1612 (Checklist B-7).32 The prints have not been trimmed and pasted to album sheets, but retain their broad, original margins, and are bound on their own paper. The current binding dates from the late eighteenth century; it may replace one commissioned by Lely, in which several Tempesta suites were gathered together.33 In the Houghton Library is a set of emblems and illustrations of martyrdoms by Tempesta, Emblemata Sacra S. Stephani Caeli Montis intercolumniis affixa, with verses by the Jesuit polygraph Giulio Roscio, printed at Rome in 1589 (Checklist B-5). This also was bound in the late eighteenth century, by Christian Kalthoeber for the collector William Beckford.34 In the Brinsley Ford collection are sets of etchings of classical antiquities and Italian drawings, intended as manuals for artists, published by Jan de Bisschop as Signorum veterum icones and Paradigmata graphices variorum artificum at The Hague in 1671 (Checklist B-1). These two suites, evidently purchased at Lely’s sale 1688 by Prosper Henry Lankrink (1628-1692), passed thereafter into the collection of William Anne Holles, 4th Duke of Essex (1732-1799), who probably commissioned their present binding.35 Examples of albums assembled by later collectors from the contents of Lely’s portfolios include two in the British Museum, both composed of the thirty-two engravings by Agostino Veneziano and Master of the Die depicting the ‘Story of Cupid and Psyche’. These sets were bound thirty or more years after Lely’s death, by different collectors, who mixed Lely’s impressions with prints they had obtained elsewhere.36

Just two of Lely’s ‘Books of prints bound’ can be identified with confidence. One is a copy of Jan Moerman’s Apologi creaturarum, a fable book with etched illustrations by Marcus Gheeraerts, published at Antwerp by Gerard de Jode in 1584 (Checklist B-2). This volume had belonged to the Swedish envoy and art collector, Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon (1594/1596-1652), who in 1637 caused it to be bound in black sheepskin (or goatskin), to match similar volumes which he kept in his country house, Vijversteyn, near The Hague. It is conceivable that Lely acquired the book directly from Spiering, who was in London at the very end of his life (4 December 1651-19 February 1652),37 but more probable that it was bought in Holland, via Gerrit Van Uylenburgh, or another of Lely’s Dutch agents, in the 1670s.38 Lely did not rebind the book; repeated throughout is the P.L monogram, added posthumously by Lely’s Executor, Roger North.39

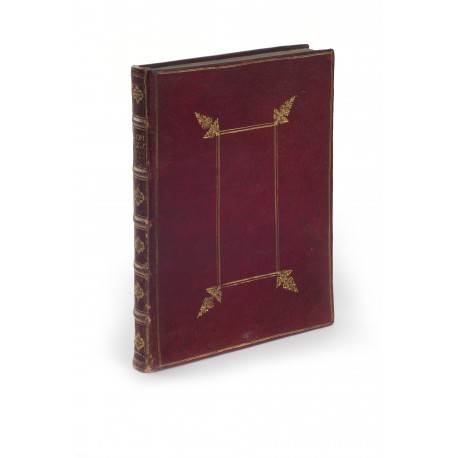

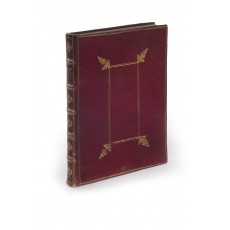

The other volume is Lely’s copy of Metamorphoseon sive transformationum Ovidianarum libri quindecim, a set of title and 150 prints by Antonio Tempesta, published at Antwerp by Petrus de Jode in 1606 (Checklist B-6).40 The prints are bound on their own paper in seventeenth-century red turkey leather, the covers decorated by gilt panels created by a two-line fillet in combination with a single-line fillet, with a flower tool placed at each outer angle; the back, divided into compartments by five raised bands, is decorated by other gilt flower tools. The binding possibly was commissioned by Lely himself, as it conforms closely to others in his library. Each print has been inkstamped P.L.

We may conjecture that Lely kept such books with his drawing and print collections, because they were an integral part of an extensive repertoire of models useful to him in his own practice, to his numerous studio assistants, and perhaps also to students in his ‘academy’.41 Lely’s formal library – transferred to the house in Kew, in September 1682, and therefore unblemished by the P.L ink ownership stamp applied six years later by Roger North – contained books of a more general nature, though some still were directly relevant to the discipline of the artist.

Judging by the volumes traced so far, Lely had a broad range of interests, or else he conceived of himself as a man of culture, who ought to be familiar with (and possess) the texts of ancient and modern poets, such as Ariosto (Checklist A-1), Boccaccio (Checklist A-2), Michael Drayton (Checklist A-3), Thomas Randolph (Checklist A-7), Spenser (Checklist A-8) and Tasso (Checklist A-8). Other books suggest an interest in contemporary political and military events: an English edition of Adam Olearius’ popular travel narrative of Muscovy and Safavid Persia (Checklist A-6), and the aforementioned English Atlas, the initial volume of which was a ‘Description of the places next to the North Pole, as also of Muscovy, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, and their several dependencies’. Lely evidently was familiar with the Dutch diplomat Lieuwe van Aitzema’s chronicle of seventeenth-century political order, since he recommended that massive work to Lord Keeper Francis North, who is supposed to have learned Dutch in order to read it.42 (If Lely possessed a copy himself, it is unknown.)

Lely’s copy of Lomazzo, A Tracte containing the artes of curious paintinge carvinge & buildinge (Oxford 1598) (Checklist A-5)

Lely had a copy of An idea of the perfection of painting (London 1668), a translation by John Evelyn of Roland Fréart de Chambray’s Idée de la perfection de la peinture… (Le Mans 1662), given to him by Evelyn himself (Checklist A-4).43 He also owned a copy of Tracte of paintinge (Oxford 1598), a translation by Richard Haydocke of the first five books of an encyclopaedia of Italian artistic theory compiled by Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo and first printed at Milan in 1584 (Checklist A-5). The front free-endpaper of that volume bears an ambiguous purchase note of its subsequent owner: ‘20 scill of Mr Lely’, which could mean that Peter Lely sold the book for 20 shillings before he was invested with the title of knight, or else that the vendor was his son, John Lely. Peter Lely was the dedicatee of Alexander Browne’s An Appendix to the art of painting in miniature or limning (London 1675);44 if he received a copy from the author, it cannot now be traced.

A copy of Thomas Randolph’s poetical and dramatic works, Poems with the Muses looking-glasse (London 1652), was given by Lely to Philadelphia Dyke (née Nutt), evidently after her marriage, in 1677, possibly after Lely’s investiture in 1679, as the copy is inscribed by her: Ex donati Petri Lillai equitis aurati pictoris celeberrimi P. Dyke (Checklist A-7). Another volume given away by Lely around the same time contained a collected edition of Spenser’s works (London 1617) bound with Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (London 1624). In addition to various inscriptions placed in the volume by Lely himself, it contains inscriptions entered by members of the Isham family of Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire (Checklist A-8). During the 1670s, Lely painted two portraits of the 3rd Baronet, Thomas Isham (1657-1681): one was finished some months before the sitter’s departure to Italy, in October 1676, for presentation to Roger Spencer, Lord Teviot; the other was painted after 1679 (both portraits are now at Lamport).45 It may be that this book became alienated from Lely’s library when Thomas Isham sat for his portrait. The signature ‘Vere Isham’ could be that of Thomas’s mother, Vere Leigh (1633-1704), second wife of the 2nd Baronet, Sir Justinian Isham (1610-1675), or else that of her granddaughter (1686-1760).46

Lely’s copy of Spenser’s works (London 1617), bound with Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (London 1624) (Checklist A-8)

Inscription on the title-page of Lely’s Tasso (Checklist A-8): LB’s gift to P Lely 1656. The identity of ‘L.B.’ is unknown, unless he should be John Baptist Gaspars, known as ‘Lely’s Baptist’

Ornament flanked by monograms of Lely and ‘LB’, drawn on an endleaf of Lely’s copy of Spenser’s works (London 1617), bound with Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (London 1624) (Checklist A-8)

The Spenser and Tasso seem to have been acquired by Lely separately, and bound-up together at a later date.47 An inscription by a previous owner on the title-page of the Spenser became cropped during rebinding; Lely effaced what remained, and added his own monogram (PEL). On the endpapers are more monograms incorporating Lely’s initials in ligature (P.L., Pe.L.) and name (P. Lely); these are closely comparable to monograms appearing on Lely’s drawings.48 On the title-page of the Tasso, employing a similar monogram, Lely has written ‘LB’s gift to PLely 1656’. In that year, Lely travelled to Holland with the architect Hugh May, sometime lodger in his house in Covent Garden, and in 1680 one of the three Executors of his estate.49 The identity of ‘L.B.’ (or B.L.) is unknown, unless he should be the painter-etcher John Baptist Gaspars (1620-1691), a former pupil in Antwerp of Anthony van Dyck and Thomas Willeboirts, who worked as a drapery painter for Lely, and became known as ‘Lely’s Baptist’.50 Another monogram combining the letters CMAVL (?) could signify Lely’s sister Catharina (or Anna Catharina) Maria, married to the burgemeester of Groenlo, near Zutphen, whom he likely visited in Holland in 1656.51

Monograms in Lely’s copy of Spenser’s works (London 1617), bound with Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (London 1624) (Checklist A-8)

The degree to which these books may have played a role in Lely’s artistic production is unclear. In a recent discussion of Lely’s subject paintings, David A.H.B. Taylor, considers Lely’s principal literary influence to be the Bible, then Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Boccaccio’s The Decameron, the last providing the probable source for Lely’s two paintings of the story of Cimon and Efigenia (Knole and Doddington Hall, respectively).52 He and other scholars have sought to affix to those pictures an edition of the text accessible to the artist. Esther van der Hoorn speculated that while Lely might have relied on William Painter’s collation of Boccaccio’s fables, The Palace of Pleasure (1556-1567), or else on John Florio’s complete English translation (1620), since he read Dutch ‘[Lely] could have also consulted the Dutch translation of 1564 by Dirck Coornhert’.53 Caroline Campbell reflected that as ‘Lely read Italian […] he did not need to use any of these translations’.54 Indeed, Lely possessed – probably among several editions – the text in the original Italian, a pocket-sized reprint of the authoritative version issued by the Giunti in 1527, published at Amsterdam by Daniel Elzevier in 1665 (Checklist A-2).55

Landscape sketch in Lely’s copy of Spenser’s works (London 1617), bound with Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (London 1624) (Checklist A-8). The Arcadian scene could have been evoked by these literary works.

Although there is some uniformity to these bindings – gold-tooled red turkey leather, panelled sides, floriated ornaments, gilt edges – it is impossible to know whether this was Lely’s personal preference; he may have taken no interest whatsoever in the binding of his books, and there is moreover some evidence that Lely handled his books carelessly.56 The comparatively plain bindings have been variously decorated using rolls and tools of generic types, which cannot be assigned to specific binderies. Prolific shops like William Nott’s, to which Lely’s Executors had paid the grand sum of £13 on 14 December 1681, for unspecified bookbinding work, employed numerous finishers, of varying abilities, working in different styles. None of Nott’s most distinctive tools – drawer-handles, four-petalled rosettes, volutes with pointillé outlines – appear on these books, however the Spencer/Tasso volume (Checklist A-8) has a gilt sun-roll on the edges of the boards and turn-ins, comb-marbled endleaves, and pink, white, and blue headbands, familiar features on many bindings associated with Nott’s shop.57

Cover decoration on books belonging to Peter Lely:

Lely's Lomazzo (Checklist A-5)

Lely's Ovid (Checklist B-6)

Lely's Spenser/Tasso (Checklist A-8)

Comparative illustration Tools associated with ‘Queen’s Binder A’ (William Nott?)58

Lely's Lomazzo (Checklist A-5)

Lely's Ovid (Checklist B-6)

Lely's Spenser/Tasso (Checklist A-8)

Lely's Spenser/Tasso (Checklist A-8)

Gilt sun-roll on Lely's Spenser/Tasso (Checklist A-8)

Checklist A – Books from Peter Lely’s Library

A / 1

Ariosto (Lodovico), Orlando furioso in English heroical verse. By Sr Iohn Harington of Bathe Knight (London: Imprinted by G. Miller for I. Parker, 1634)

subsequent provenance

- Victor Albert George Child Villiers, 7th Earl of Jersey (1845-1915)

- Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Osterley Park library: catalogue of this important collection of books, the property of the Rt. Hon. the Earl of Jersey, 6-14 May 1885, p.7, lot 83 (‘fine copy, with autograph of Sir P. Lely, in old English red morocco, gilt edges’; link)

- Pickering, London - bought in sale (£12 15s)

- Robert Hoe (1839-1909)

- Anderson Auction Company, Catalogue of the library of Robert Hoe of New York; illuminated manuscripts, incunabula, historical bindings, early English literature, rare Americana, French illustrated books, eighteenth century English authors, autographs, manuscripts, etc., part III, 15-19, 22-26 April 1912, p.191, lot 1427 (‘contemporary red morocco, gilt edges… The autograph of Sir Peter Lely is on the first title’; link) – Sold for $10 (American Book Prices Current, 1912, p.31; link) [RBH 15Apr1912-1427]

- San Marino, Huntington Library, 99001 (‘signatures of [Sir] P[eter] Lely, and Robert Hoe 1885’; OPAC)

citation

James O. Wright and Carolyn Shipman, Catalogue of books by English authors who lived before the year 1700, forming a part of the library of R. Hoe (New York 1903-1905), II, p.320 (‘contemporary red morocco, gilt back and side panels, gilt edges… The autograph of Sir Peter Lely is on the first title’; link)

A / 2

Boccaccio (Giovanni), Il Decameron di Messer Giovanni Boccacci, cittadino Fiorentino. Si come le diedero alle stampe gli SSri Giunti l’anno 1527 (Amsterdam: [Daniel Elzevier], 1665)

subsequent provenance

- Pickering & Chatto, Catalogue of old and rare books (London 1895), p.145, item 1362 (‘Contemporary red morocco extra, gilt edges, with the autograph of Sir Peter Lely, the celebrated portrait painter, on title, £4 4s’; link); Catalogue of old and rare books; and a collection of valuable old bindings (London 1900), p.112, item 1037 (‘contemporary red morocco extra, gilt edges, with the autograph of Sir Peter Lely, the celebrated portrait painter, on title, £4 4s’; link)

- J. Pearson & Co., One hundred books from the cabinets of royal and distinguished bibliophiles from Grolier to Beckford (London 1901), p.34, item 35 (‘Contemporary red morocco, gilt edges. Sir Peter Lely’s copy, with his signature on the title-page. Examples from the library of this great painter are very rare. 25 guineas’; link)

- [anonymous consignor to] Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable & rare books and illuminated and other manuscripts, 11-15 December 1903, lot 714 (‘old morocco extra… Sir Peter Lely’s copy; his autograph is on the title-page. Examples of his library are rare’)

- ‘Buck’ - bought in sale (£1 5s) (Book Prices Current, volume 18, 1904, p.124, entry 1472) [RBH Dec111903-714]

- J. Pearson & Co., A unique and extremely important collection of autograph letters of the world’s greatest painters of the XVth, XVIth, XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries (London c. 1911), p.12, item 29 (‘His signature, affixed to the title page of the Elzevir edition of “Il Decameron,” 1665. £8 8s’; link)

citation

- [W.C. Hazlitt,] ‘English and Scottish book collectors and collections – Part II’ in The Bookworm; an illustrated treasury of old-time literature 7 (1894), p.102 (‘With his autograph on title’; link)

A / 3

Drayton (Michael), Poly-Olbion or A chorographicall description of tracts, riuers, mountaines, forests, and other parts of this renowned isle of Great Britaine (London: Printed by H[umphrey] L[ownes] for Mathew Lownes: I. Browne: I. Helme, and I. Busbie, 1613)

subsequent provenance

- [possibly William Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Devonshire (1673-1729), a buyer in second sale of the Lely collection, also in the Prosper Henry Lankrink sales in 1693-1696; by descent]

- Chatsworth, Dukes of Devonshire

citation

- James Phillip Lacaita, Catalogue of the library at Chatsworth (London 1879), II, pp.57-58 (‘Sir P. Lely’s copy, with his autograph on the title-page’; link)

A / 4

Fréart de Chambray (Roland), An idea of the perfection of painting : demonstrated from the principles of art, and by examples conformable to the observations, which Pliny and Quintilian have made upon the most celebrated pieces of the ancient painters, parallel’d with some works of the most famous modern painters, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Julio Romano, and N. Poussin (London: In the Savoy: printed for Henry Herringman at the sign of the Anchor in the lower-walk of the New-Exchange 1668)

provenance

- Presentation inscription by the translator, John Evelyn (1620-1706), to Peter Lely

- Pickering & Chatto, The Book Lovers’ Leaflet no. 245: A Collection of old and rare books of (with some exceptions) English literature. Addenda (Cum-Hey) (London c. 1926-1928), p.1873, item 12356a (‘original calf, Presentation copy from Evelyn to Sir Peter Lely, with autograph inscription, ‘For my honor’d friend | Mr Lely from his | humble servt. | J. Evelyn.’ … and with seven corrections in text in Evelyn’s hand, including the filling in of one word in preface, in all copies left blank: Fine copy. £95’; link)

- Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, *EC65.Ev226.668f (‘Inscribed on front flyleaf: For my honor’d Friend Mr. Lilly [i.e. Sir Peter Lely], from his humble Sert.: Evelyn’; bound in ‘Full contemporary calf’; OPAC)

A / 5

Lomazzo (Giovanni Paolo), A Tracte containing the artes of curious paintinge carvinge & buildinge (Oxford: By Ioseph Barnes For R.H. [Richard Haydocke], 1598)

subsequent provenance

- Unknown purchaser from Peter (or John) Lely, inscription on endleaf ‘20 Sc[h]il[lings] of Mr Lely’

- Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke (1690-1764), armorial bookplate (Philip Lord Hardwicke | Baron of Hardwicke | in ye County of Gloucester, [motto] nec cupias nec metuas)

- by family descent, Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire, until 1894, when the estate sold to Thomas Agar-Robartes, 6th Viscount Clifden (1844-1930)

- by descent, until consigned by Francis Agar-Robartes, 7th Viscount Clifden (1883-1966), to

- Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, comprising a selected portion of the library at Wimpole hall, Royston, the property of the Rt. Honble. Viscount Clifden, 22-23 July 1937, lot 115 (‘engraved title, slightly defective and laid down, engravings, wants leaf bearing imprint, stained and cut into, old red morocco gilt, panelled sides, g.e., sold not subject to return’) – Sold to ‘Edwards, £5’ (Book Auction Records, volume 34, 1937, p.595)

- Christie’s, ‘Printed books; the property of a charitable trust, the trustees of the Stoneleigh Settlement, the executors of the late 4th Lord Leigh, Stoneleigh Abbey Preservation Trust Ltd and from various sources’, 18 November 1981, lot 191, lot 260 (‘seventeenth century English red morocco, side panelled in gilt, spine gilt, bookplate of Lord Hardwicke… A note in a late seventeenth century hand reads: ‘20 Scill of Mr Lely’. The name is uncommon in England and this very likely refers to Sir Peter Lely.’) – Sold to Alan Thomas, £1200 (Book Auction Records, volume 79, 1982, p.342)

- Dr Howard Knohl, Foxe Pointe Library, Anaheim Hills, CA, consigned to

- Sotheby’s, Selections from the Fox Pointe Manor Library, New York, 26 October 2016, lot 191 ($15,000; RBH n09753-191]

- T. Kimball Brooker, Chicago

- Sotheby’s, Bibliotheca Brookeriana III: Art, architecture and illustrated books, London, 9 July 2024, lot 561 [catalogue online, link]

- unidentified owner - bought in sale (£22,860) [RBH L24402-561]

A / 6

Olearius (Adam), The voyages and travells of the ambassadors sent by Frederick, Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy and the King of Persia : begun in the year M. DC. XXXIII. and finish’d in M. DC. XXXIX : containing a compleat history of Muscovy, Tartary, Persia, and other adjacent countries (London: printed for John Starkey, and Thomas Basset, at the Mitre near Temple-Barr, and at the George near St. Dunstans Church in Fleet-street, 1669)

subsequent provenance

- Frederick Clarke (1830-1903), Ormond House, Wimbledon

- Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of the valuable library of the late Frederick Clarke (of Ormond House, Wimbledon), 31 October 1904, p.62, lot 851 (‘old morocco extra, g.e.’)

- Ellis (J.J. Holdsworth & G. Smith), London - bought in sale (£1 10s) (Book Auction Records, volume 2, 1905, p.107); their Catalogue 112: Rare and valuable books including incunabula (London 1906), item 584 (‘Sir Peter Lely’s copy … old English red morocco, panelled sides, full gilt back, gilt edges, by Mearne, £4 4s. A fine copy, with the autograph of Sir Peter Lely on the title-page’)

- Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of fine books, illuminated & other manuscripts, and valuable bindings, 17-18 October 1918, lot 219 (‘old morocco gilt, gilt edges, autograph of Sir Peter Lely on title, w.a.f’)

- Ellis, London - bought in sale (£5 10s) (Book Auction Records, volume 16, 1919, p.58; link) [RBH Oct171918-219]

- Sir Robert Leicester Harmsworth, 1st Bt (1870-1937)

- Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of a rare and valuable collection of voyages and travels, early atlases, manuscript collections and autograph letters of African explorors, etc., forming part of the reknowned library originally formed by the late Sir R. Leicester Harmsworth, bt., LL.D. (and now sold by order of the trustees), London, 28-29 June 1939, lot 1391

- Maggs Bros, London - bought in sale (£6 10s) [RBH 28Jun1939-1391]

- Chas. J. Sawyer, Ltd, Catalogue 239: Fine books including Africana, Robert Boyle's first work, coloured plate books (London 1957), item 531 (£21; ‘Sir Peter Lely’s copy … contemporary English red morocco extra, gilt line panels with corner ornaments on sides, gilt tooled back, gilt edges, with signature of Sir Peter Lely on title-page’) [RBH 239-531]

- Dublin, Chester Beatty Library, Inventory AD441, RSN 1344 [link]

citations

- Frederick Clarke, ‘Sir Peter Lely, 1617-1680’ in Contributions towards a Dictionary of English Book-Collectors as also of some Foreign Collectors whose libraries were incorporated in English collections or whose books are chiefly met with in England, edited by Bernard Alexander Christian Quaritch (London 1892-1921; reprinted London 1969), part IV (April 1893), p.183 (‘bears the painter’s well-known autograph on the title-page… none of [Lely’s] biographers mention his books’)

- [W.C. Hazlitt], ‘English and Scottish book collectors and collections – Part II’ in The Bookworm; an illustrated treasury of old-time literature, volume 7, 1894, p.102 (‘With Lely’s autograph’; link)

A / 7

Randolph (Thomas), Poems with the Muses looking-glasse. Amyntas. Jealous lovers. Arystippus. The fourth edition inlarged (London: [s.n.], Printed in the yeere 1652)

subsequent provenance

- Philadelphia Dyke, daughter of Sir Thomas Nutt, of Selmeston, Sussex, and Philadelphia Nutt; married 1677 Thomas Dyke, 1st Baronet (c. 1650-1706), of Horeham, Sussex

- Thomas Thorpe, A General Catalogue of an interesting and valuable collection of rare, curious, and useful books in all languages and branches of literature, Part III (London 1830), p.148, item 11340 (‘old morocco, gilt leaves, 15s. This copy was the gift of Sir Peter Lely, Knt., the famous painter, to Philadelphia Dyke’; link)

- Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, *EC R1598 638pd (‘Inscribed: Ex donati Petri Lillai equitis aurati pictoris celeberrimi P. Dyke [&] The Gift of Sr Peter Lilly Kt. the most famous painter of the age, to Philadelphia Dyke’; ‘Contemporary maroon calf, gilt’; OPAC)

A / 8

Spenser (Edmund), The faerie queen: The shepheards calendar: together with the other works of England’s arch-poët, Edm. Spenser: collected into one volume, and carefully corrected ([London]: printed by H[umphrey]. L[ownes]. for Mathew Lownes, 1617) — Bound with: Tasso (Torquato), Godfrey of Boulogne: or The recouerie of Ierusalem. Done into English heroicall verse, by Edward Fairefax Gent. (London: Printed by [Eliot’s Court Press, for] Iohn Bill, 1624)

provenance

- Spenser: illegible ownership inscription on title-page (cropped by binder’s knife when rebound), marginal annotations, some likewise cropped

- [possibly John Baptist Gaspars (1620-1691), known as ‘Lely’s Baptist’], inscription (on title-page of Tasso): LB’s gift to P Lely 1656

- Peter Lely (1618-1680), inscriptions and monograms on title-pages and endpapers

- [possibly Thomas Isham, 3rd Baronet (1657-1681)], inscriptions and pen trials, including ‘Vere Isham’ [probably Vere Leigh (1633-1704), second wife of the 2nd Baronet, Sir Justinian Isham (1610-1675); or else her granddaughter (1686-1760)], by family descent, Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, to

- Sir Vere Isham, 11th Baronet (1862-1941), by whom consigned to

- Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of valuable old English books and manuscripts, selected from the library of a gentleman in the country, 17-18 June 1904, lot 311 (‘old English morocco gilt, gilt edges… This volume was formerly Sir Peter Lely’s. It has his autograph twice on the fly-leaf of the Spenser, with some sketches; and also on the title of the Tasso’) – Sold to Ellis (J.J. Holdsworth and George Smith), 29 New Bond Street, London, £10 10s (Book Prices Current, volume 18, 1904, p.578, item 5809; link)

- Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919)

- Sotheby, Catalogue of a further portion of the valuable library collected by the late Charles Fairfax Murray, 17-20 July 1922, p.104, lot 980 (‘inscription “P. Lely” on fly-leaf in a 17th century hand… inscription on title [of Tasso] “B.L.’s (or L.B.’s) gift to P. Lely, 1656,” title backed, wants portrait… in 1 vol., old morocco, gilt, g.e., sold not subject to return’)

- Edwin Parsons, London - bought in sale (£1) (Book Auction Records, volume 19, 1922, p.716)

- Maggs Bros, London; their Catalogue 446: English literature: manuscripts and printed books, 14th to the 18th centuries selected from the stock of Maggs Bros.; with sixty-one illustrations (London 1924), p.511 no. 2087 (‘17th century English red morocco, g.e. … From the Library of the celebrated English Painter, Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680), with his Autograph Signature several times repeated’; link)

- Henry Sotheran Ltd, London, offered at ABA Olympia book fair, 26-28 May 2016 (link)

- New York, Morgan Library & Museum, 199181 (opac [link])

citations

- Charles Edmonds, An annotated catalogue of the library at Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, the seat of Sir Charles E. Isham, Bart. including copious notes and observations on the rare, unique, and hitherto-unknown books of English poetry, early English plays, and prose works, as well as on other interesting books and manuscripts preserved therein ([England: publisher not identified], 1880), p.5 (‘Various autograph signatures… Sir Peter Lely (who painted the Portrait of Sir Thomas Isham), with a pen sketch by him, and the Initials of Miss Vere Isham, in Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Jerusalem. Page 222 [in Edmonds’ manuscript catalogue of the library, now lost])

- Douglas Gordon, ‘The Book-Collecting Ishams of Northamptonshire and Their Bookish Virginia Cousins’ in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 77 (1969), pp.174-179 (p.176, appearance in 1904 sale cited)

- H.A.N. Hallam, ‘Unfamiliar libraries XII: Lamport Hall revisited’ in The Book Collector 16 (1967), pp.439-449 (p.448: ‘There was, for instance, a volume of Fairfax’s translation of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata 1621, bound with Spenser’s Faerie Queen 1617. This contained the signature of Sir Peter Lely, who painted the portrait of Sir Thomas Isham, of which there are two versions in the house, with a pen sketch by him. This volume, which realized two guineas only, has disappeared from view after its sale in 1921 to a dealer who has since died’.)

- Oliver Millar, Sir Peter Lely 1618-80 [catalogue of the] exhibition at 15 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1 [from 17 November 1978-18 March 1979] (London 1978), p.12 (cited)

- David A.H.B. Taylor, ‘Lely in Arcadia: Religious, pastoral, musical and mythological themes in Peter Lely’s subject pictures’ in Peter Lely: a lyrical vision, edited by Caroline Campbell, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Courtauld Gallery, London, 11 October 2012-13 January 2013 (London [2012]), p.67 (cited incorrectly)

Checklist B – Bound suites of prints from Peter Lely’s Print collection

B / 1

Bisschop (Jan de), Signorum veterum icones. – Bound with: Paradigmata graphices variorum artificum ([s.l.; Amsterdam or The Hague?], c. 1668-1671)

provenance

- Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092-2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

- [presumably auction sale of prints and drawings belonging to Lely, at his house in the Great Piazza, Covent Garden, 16 April 1688]

- Prosper Henry Lankrink (1628-1692) (Lugt 2090; link), who spent £242 17s in Lely’s 1688 auction

- [presumably auction sale of the library of Prosper Henry Lankrink at his house in Covent Garden, 29 May 1693 (link); or in auction sales of Lankrink’s prints and drawings, 8 May 1693 (link), 22 February 1694 (link)]

- Algernon Capell, 2nd Earl of Essex (1670-1710), by descent to

- George Capel-Coningsby, 5th Earl of Essex (1757-1839), by whom given in 1827 to his son-in-law

- Richard Ford (1796-1858), by descent to

- Brinsley Ford (1908-1999), by descent to

- Augustine Ford (b. 1943), London

citation

- Brinsley Ford, Charles Avery and John Mallet, ‘Richard Ford (1796-1858)’ in The Volume of the Walpole Society 60 (1998), p.26 (‘Two of the most beautiful books in the library were given by Lord Essex to Richard Ford in 1827 – the two volumes of etchings by Ian Bisschop published in The Hague in 1671… These volumes belonged to Sir Peter Lely, since each plate bears his collector’s mark. On Lely’s death the volume passed to P.H. Lankrink who also added his collector’s mark to all the plates…’)

- Diana Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’ in Collecting prints and drawings in Europe, c. 1500-1750, edited by Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam, and Genevieve Warwick (Aldershot 2003), pp.137-138 (‘every individual page has the PL stamp, North’s numbering system appears just once on the title-pages’)

B / 2

Moerman (Joannes), Apologi creaturarum ([Antwerp]: [Christopher Plantin for Gerard de Jode], 1584)

provenance

- Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon (c. 1594/1597-1652), for whom bound in 1637

- Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092-2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

- Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of… the Beckford Library, removed from Hamilton Palace, London, 30 June-11 July 1882, lot 2521 (‘fine impressions, each plate stamped P.L. on margin, old black morocco’)

- Betrnard Quaritch, bought in sale (£9 10s); their General Catalog of Books Offered to the Public at the Affixed Prices (London 1883), p.1390 no. 13788 (link)

- Alfred Denison (1816-1887), Ossington Hall, Nottinghamshire, by descent to his nephew, William Evelyn Denison (1843-1916), consigned by the latter’s widow, Lady Elinor Denison (1850-1939), to

- Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the celebrated collection of books relating to angling and of a small general library formed by the late Alfred Denison, London, 17 July 1933, lot 158

- Sexton - bought in sale (£4 15s) (Book Auction Records, volume 30, 1933, p.469)

- Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of valuable printed books, illuminated & other manuscripts, autograph letters & historical documents, London, 18 December 1933, lot 79 (offered among ‘Other properties’; ‘black morocco, Hamilton Palace (Beckford collection) and Arthur [sic] Denison bookplates’)

- Sherwood, bought in sale (12s) (Book Prices Current, volume 48, 1934, p.503)

- J.H. Gispen, Nijmegen

- J.L. Beijers, ‘The fine library of the late J.H. Gispen, Esq.’, Utrecht, 29 May 1973, lot 185 (‘From the Hamilton Palace Library’)

- Amsterdam, University Library (link)

citations

- H. de la Fontaine Verwey, ‘Het mysterie van de zwarte banden met het jaartal 1637’ in Bibliotheekinformatie: Mededelingenblad voor de Wetenschappelijke Bibliotheken 11 (1973), pp.11-14 (speculating wrongly that the binding was commissioned by Hendrick Van den Borcht, who in 1637 was appointed curator of the Earl of Arundel’s collections)

- Jan Gerrit van Gelder and Ingrid Jost, Jan de Bisschop and His Icones & Paradigmata: Classical Antiquities and Italian Drawings for Artistic Instruction in Seventeenth Century Holland (Doornspijk 1985), p.203 note 30: ‘once owned by Sir Peter Lely whose collector’s mark (L. 2092) is to be found on all sixty-five illustrations in the book’

- Diana Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’ in Collecting prints and drawings in Europe, c. 1500-1750, edited by Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam, and Genevieve Warwick (Aldershot 2003), p.137

- Ilja M. Veldman, ‘Portrait of the artist as an art collector: Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon’ in Simiolus 38 (2015-2016), pp.228-249 (p.242, citing this volume).

B / 3

Müller (Theobald), Mvsaei Ioviani Imagines Artifice manu ad viuum expressae. Nec minore industria Theobaldi Mvlleri Marpurgensis Musis illustratae (Basel: Peter Perna for Heinrich Petri, 1577)

provenance

- Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092-2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

- Dawson’s Book Shop, Manuscripts, Incunabula & Books of Famous Presses (Los Angeles 1932), item 52 (‘130 woodcut portraits with Latin verse for each. Initials “P. L.” stamped on each cut. Roman and italic type. Pencilled note on fly-leaf “Sir Peter Lely’s copy.” Old mottled calf, hinges cracked’)

B / 4

Perrier (François), Ill.mo D.D. Rogerio Duplesseis dno de Lioncourt Marchioni de Montfort, comiti de la Rochegvion … Heroi virtutum et magnarum artium eximio cultori. Auorum pace belloque præstantium et ævi melioris decora referenti; Segmenta nobilium signorum e[t] statuarii, quæ temporis dentem inuidium euasere Urbis æternæ ruinis erepta typis æneis ab se commissa perptuæ uenerationis monumentum (Paris: [s.n.], 1638)

provenance

- Peter Lely, inscription, ownership stamp (Lugt 2092-2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

- Maggs Bros, London; their Catalogue 279: Books on art and allied subjects, Part II: K-Z (London 1912), item 1683 (‘orig. calf, rebacked, and gilt Sir Peter Lely’s copy (the famous painter), with his rare autograph on title and his stamp on each plate. Plate no. 63 wanting’)

B / 5

Roscius (Julius Hortinus), Emblemata sacra S. Stephani Caelii Montis intercolumniis affixa ([Rome: publisher not identified], 1589)

provenance

- Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092-2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

- William Beckford (1772-1857), re-bound for him by Christian Samuel Kalthoeber

- George Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford and later 5th Duke of Marlborough (1766-1840)

- R.H. Evans, White Knights library: Catalogue of that distinguished and celebrated library, London, 7-19 June 1819, p.68, lot 1532 (‘blue morocco, joints’)

- Richard Heber (1773-1833), his note of purchase in the White Knights sale (Bibliotheca Blandfordiana)

- R.H. Evans, Bibliotheca Heberiana; catalogue of the library of the late Richard Heber, Esq., Part VI, 8 April 1835 (15th Day), p.238, lot 3236 (‘blue morocco, Sir Peter Lely’s copy’; link)

- Isaac Comstock Bates (1843-1913), Providence, RI (‘stamp’, presumably Lugt 222f-g; link)

- Ellen D. Sharpe (1861-1953), Providence, RI, her bequest to

- Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, Printing & Graphic Arts Collection, Typ. 525.89.752 (‘stamp’) (link) (link)

citation

- Harvard College Library, Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, Catalogue of books and manuscripts. Part 2, Italian 16th century books, compiled by Ruth Mortimer (Cambridge 1974), II, pp.616-617 no. 447 (‘blue straight-grain morocco by Kalthoeber’, ‘Beckford copy, with the initials of Peter Lely stamped on each engraving, Heber’s note of purchase from the White Knights sale, and stamp of Isaac C. Bates’)

B / 6

Tempesta (Antonio), Metamorphoseon sive Transformationum Ovidianarum libri quindecim, aeneis formis ab Antonio Tempesta Florentino incisi, et in pictorum, antiquitatisque studiosorum gratiam nunc primum exquisitissimis sumptibus a Petro de Iode Antverpiano in lucem editi (Antwerp: Pieter de Jode, 1606)

provenance

- Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092-2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

- Mr A. Goodwin, 39 High Street, Tunbridge Wells

- London, British Museum, 1893,0411.15.1-151 (163*.a.33)

B / 7

Veen (Otto van), Historia septem infantium de Lara (Antwerp: Philip Lisaert, 1612)

provenance

- Peter Lely, with his ownership stamp (Lugt 2092-2094; link) added posthumously by Roger North

- Society of Writers to Her Majesty’s Signet, Edinburgh

- Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of important old master engravings and etchings, London, 11 June 1959, p.36 lot 138 (offered as ‘The Property of the Society of Writers to Her Majesty’s Signet removed from the Signet Library, Edinburgh’, ‘from the Sir Peter Lely collection’, bound in ‘calf, name of artist, on straight-grained morocco inlaid in centre of upper cover, oblong folio’)

- Glasgow, University Libraries, S.M. Add. 14

citations

- Signet Library, A second supplement to the Catalogue of books in the Signet library, 1882-1887, compiled by Thomas Graves Law (Edinburgh 1891), III, p.166 (link)

- Michael Bath, ‘The Proofs of Antonio Tempesta’s Engravings for Historia Septem Infantium de Lara: Glasgow University Library, S.M. Add.14’ in Emblematica: an Interdisciplinary Journal for Emblem Studies 20 (2013), pp.405-413 (wrongly interpreting Lely’s inkstamped monogram as the initials of the printer)

1. Diana Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’ in Collecting prints and drawings in Europe, c. 1500-1750, edited by Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam, and Genevieve Warwick (Aldershot 2003), pp.123-139.

2. Frederick Clarke, ‘Sir Peter Lely, 1617-1680’ in Contributions towards a Dictionary of English Book-Collectors as also of some Foreign Collectors whose libraries were incorporated in English collections or whose books are chiefly met with in England, edited by Bernard Alexander Christian Quaritch (London 1892-1921; reprinted London 1969), part IV (April 1893), p.183, remarking ‘none of [Lely’s] biographers mention his books’. See Checklist A-6.

3. [W.C. Hazlitt], ‘English and Scottish book collectors and collections, Part II’ in The Bookworm; an illustrated treasury of old-time literature 7 (1894), p.102 (‘specimens of his library are very uncommon’). See Checklist A-2.

4. Oliver Millar, Sir Peter Lely 1616-80, catalogue of an exhibition organised by the National Portrait Gallery, 17 November 1978-18 March 1979 (London 1978), p.12. Diana Dethloff, ‘Lely, Sir Peter (1618-1680)’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (online edition, May 2009; accessed 19 Nov 2016). David A.H.B. Taylor, ‘Lely in Arcadia: Religious, pastoral, musical and mythological themes in Peter Lely’s subject pictures’ in Peter Lely: a lyrical vision, edited by Caroline Campbell, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Courtauld Gallery, London, 11 October 2012-13 January 2013 (London [2012]), p.67.

5. Kew, Public Record Office, PCC, Prob/11,365, ff. 45 verso-47. Reprinted in Wills from Doctors’ Commons: a selection from the wills of eminent persons proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 1495-1695, edited by John Gough Nichols and John Bruce (London 1863), pp.133-137 (link).

6. Lely’s common-law wife, Ursula, had died during childbirth, in 1673. See The registers of St. Paul’s Church, Covent Garden, London. Volume I: Christenings, 1653-1752, edited by William H. Hunt (London 1906), p.41, an entry on 7 January 1673 for ‘Peter Son of Peter Lely by Vrcila, his reputed wife’; and The Registers of St Paul’s Church, Covent Garden, London. Volume 4: Burials, 1653-1752, edited by William H. Hunt (London 1908), p.64, entries for her burial on 11 January 1673 (‘Vrsilla Lelly In the Church’) and that of the infant on 16 January 1673 (‘Peter Son of Peter Lelly In the Church’). A drawing by Lely of Ursula as a young woman was sold by Sotheby’s, Old Master and British Works on paper including drawings from the Oppé Collection, 5-6 July 2016, lot 218 (link).

7. J.A.C.Ab. Wittenaar, ‘De geboorteplaats en de naam van Peter Lely: nieuwe documenten’ in Oud Holland 67 (1952), pp.122-124. Catharina was the widow of Coenraedt Wecke (d. 1672), burgemeester of Groenlo, near Zutphen (1647-1672). By this date, Lely’s father, Johan van der Faes, alias Lelij (1592-c. 1643); mother, Abigael, née van der Vliet (?-after 1661); and elder sister Anna (1616-c. 1655) were dead.

8. British Library, Add Ms 16,174. The Executors’ account book is examined by Mansfield Kirby Talley, ‘Extracts from the Executors Account-Book of Sir Peter Lely, 1679-1691: an account of the contents of Sir Peter’s studio’ in The Burlington Magazine 120 (1978), pp.745-749; and Diana Dethloff, ‘The Executors’ Account Book and the dispersal of Peter Lely’s collection’ in Journal of the History of Collections 8 (1996), pp.15-51.

9. British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 26 verso.

10. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Volume IX, 1668-1669, edited by Robert Latham and William Matthews (London 1976), p.480 (12 March 1669).

11. On the presumable identification of Nott as ‘Queens’ Binder A’, see Howard M. Nixon, British bookbindings presented by Kenneth H. Oldaker to the Chapter Library (London 1982), p.22 (with earlier literature); Howard Nixon and Mirjam Foot, The History of decorated bookbinding in England (Oxford 1992), p.74.

12. British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 29 recto.

13. Printed ‘Proposals’, inviting subscriptions to this work (projected in eleven volumes), were issued c. 1678 and c. 1679/1680; Lely is named among committed subscribers in both: Moses Pitt, Proposals for printing a new Atlas (London: s.n., 1678) [Wing P2308], p.3, as ‘Peter Ely’ [sic]; Proposals for printing the English Atlas (London: s.n., 1679/1680?) [Wing P2308B], p.3, as ‘Sr. Peter Lely of London’. According to the antiquary George Vertue, Lely was knighted at Whitehall on 11 June 1679; Millar, op. cit., p.15, gives the date January 1680. Lely is not named in Pitt’s Catalogue of the Subscribers Names to the English Atlas, now Printing at the Theater in Oxford (Oxford, before 14 June 1680) [Wing C1411aA]. In this announcement, Pitt advises his subscribers that ‘the first Volume is finished… and will be delivered to the said Subscribers on the 24th of June 1680 on the paiment of 40s. more for the next Volume’.

14. In about 1651, Lely had become a tenant of nos. 10-11, the two easternmost buildings in the north range of the Great Piazza, Covent Garden, sharing the house initially with the Dutch painter and framemaker Tobias Flessiers and Hugh May; by 1662, Lely is recorded as the only ratepayer. The superior landlord was the Earl of Bedford. Millar, op. cit., pp.14, 28 (footnote 21). These portico buildings were demolished in 1858 for the erection of the Opera House and the Floral Hall; cf. Survey of London: Volume 36, Covent Garden, edited by F.H.W. Sheppard (London 1970), pp.88-89. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol36/pp88-89 [accessed 11 November 2016] (link).

15. Millar, op. cit., p.17.

16. Talley, op. cit., pp.745-749. Sale of artists’ materials from Sir Peter Lely’s studio, at the Great Piazza in Covent Garden, 1681; in ‘The art world in Britain 1660 to 1735,’ at http://artworld.york.ac.uk; accessed 18 November 2016 (link).

17. Quotations from Roger North’s autobiography (British Library, Add Ms 32,506); Roger North, Notes of me: the autobiography of Roger North, edited by Peter Millard (Toronto 2000), p.239.

18. The names of individual buyers and prices realised are recorded in the Account Book; see Dethloff, ‘The Executors’ Account Book and the dispersal of Peter Lely’s collection’, op. cit., pp.15-51. Part of the 1682 sale catalogue was published by C.H. Collins Baker, Lely and the Stuart portrait painters: a study of English portraiture before and after Van Dyck (London 1912), II, pp.144-149; the catalogue is reprinted in its entirety in ‘Editorial: Sir Peter Lely’s Collection’ in The Burlington Magazine 83 (1943), pp.185-91. See also Henry Ogden and Margaret Ogden, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s Collection: further notes’ in The Burlington Magazine 84 (June 1944), p.154. Sale of the picture collection of Sir Peter Lely at the Great Piazza in Covent Garden, 18 April 1682; in ‘The art world in Britain 1660 to 1735,’ at http://artworld.york.ac.uk; accessed 18 November 2016 (link).

19. British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 30 recto: ‘to porters for carrying the drawings… 00-05-00’ (14 June 1682); ‘to porters for removing ye remaining pictures & prints… 00-09-00’ (27 June 1682), ‘For porters for removing the prints…00-04-06’ (28 September 1682). See Dethloff, ‘The Executors’ Account Book and the dispersal of Peter Lely’s collection’, op. cit., pp.19-20.

20. British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 29 recto.

21. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., pp.237-238; Roger North, Life of the Lord Keeper North, edited by Mary Chan (Lewiston, NY 1995), pp.196-198. The house was demolished in 1765.

22. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., pp.249-252. Allegations for marriage licences issued by the Vicar-General of the Archbishop of Canterbury, July 1687 to June 1694, edited by George J. Armytage (London 1890), p.281.

23. Notice of John Lely’s death in London Evening Post, 12 November 1728: ‘Last Week died at his House on Kew Green, near Richmond in Surrey, and on Tuesday was buried at the Chapel there, John Lely, Esq; a Gentleman of good Character, and of a very extensive Charity; he was Son and Heir to Sir Peter Lely, the famous Painter, who left him a great Estate.’ (link). John Lely had been among the subscribers for the Parish Church of St Anne, Kew Green (consecrated on 12 May 1714).

24. Daily Post, 23 January 1729 (link):

To be sold by AUCTION, On Friday the 31st of this Instant, at Mr. COCK’s Auction-Room, in Poland-street, near Golden-Square, THE Plate of the Right Hon. the Earl of LINCOLN, deceased, consisting of great Variety of Gilt and other Plate; as Dishes, Plates, Cisterns, Fountains, and whatever else is useful or ornamental, of the newest Fashion. To which is added, The Collection of Paintings belonging to Mr. LELY; of Kew-Green, deceased, collected by his Father, the famous Sir PETER LELY. As likewise many other Curiosities, Particularly a very curious Musical Clock, which plays great Variety of the most celebrated Opera and other Tunes, with many rare Mathematical Movements, &c. being one of the finest yet made by Mr. Pinchbeck; two large and fine Lapis Lazula Tables; a Harpsichord of the Silver Tone, by the famous Hans Rucker upwards of 40 very rich Cravats and Ruffles, of the finest Point, Mechlin, and Flanders lace; several very curious repeating Watches, Equipages, Snuff-Boxes, &c. set with Diamonds, and other Jewels; a large Quantity of the old Japan China; several very rich Sets of Horse Furniture, Pistols, &c. The Collection may be view’d at the Plate aforesaid on Monday the 27th, and every Day after till the Hour of Sale, which will begin each Day at 11 o’Clock in the Forenoon. Catalogues to be had on the first Day of Showing, Gratis, at the Place of Sale. N.B. There are two very good Chariots of my Lord’s to be sold in the first Day’s Sale. And the House of Mr. LELY, on Kew-Green, is to be lett. Enquire of Mr. Cock.

25. British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 79 verso: ‘Advertisements in the Gazett… 1-0-0’ (i.e. London Gazette, 13 February 1688, link; London Gazette, 9 April 1688, link); ‘For composing printing publishing and dispersing the advertisements at Paris… 2-0-0’; ‘For the Advertisement in Holland…0-10-0’.

26. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., p.244.

27. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., p.244. Cf. London Gazette, 4 March 1689: ‘Whereas the sale of the Remainder of Sir Peter Lely’s Italian Drawings and Prints, was put off to the beginning of April next: Now it is thought fit to give Notice, that the said sale is put off to a farther time; but the same not being yet appointed, it is declared that before the sale is resumed, timely notice shall be given thereof by publick Advertisement’ (link).

28. Sale of pictures of Dr Henry Davenant, including drawings from Sir Peter Lely’s collection, at Parry Walton’s premises in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 2 February 1694 (link); Sale of the remaining drawings of Sir Peter Lely, at the premises of Parry Walton in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, November 1694 (link). ‘The art world in Britain 1660 to 1735,’ at http://artworld.york.ac.uk; accessed 18 November 2016 (link). London Gazette, 17 September 1694 (link), 22 October 1694 (link), 8 November 1694 (link).

29. Roger North, Notes of me, op. cit., p.244.

30. British Library, Add Ms 16,174, f. 85 verso. Cf. Dethloff, ‘The Executors’ Account Book and the dispersal of Peter Lely’s collection’, op. cit., p.40.

31. Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’, op. cit., pp.136-137.

32. University of Glasgow Library, Stirling Maxwell Collection, SM 14 (OPAC, image). Cf. Michael Bath, ‘The Proofs of Antonio Tempesta’s Engravings for Historia Septem Infantium de Lara: Glasgow University Library, S.M. Add.14’ in Emblematica: an Interdisciplinary Journal for Emblem Studies 20 (2013), pp.405-413, interpreting the ‘P.L.’ monograph as the initials of the publisher.

33. The upper cover of the binding is inlaid with a goatskin panel lettered ‘Antonio Tempesta’ (Bath, op. cit., fig. 1). One of the binder’s endleaves is watermarked ‘1796’ (private communication from Julie Gardham, Senior Assistant Librarian, University of Glasgow Library, 5 December 2016).

34. Harvard College Library, Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, Catalogue of books and manuscripts. Part 2, Italian 16th century books, compiled by Ruth Mortimer (Cambridge 1974), II, pp.616-617 no. 447 (‘blue straight-grain morocco by Kalthoeber’, ‘Beckford copy, with the initials of Peter Lely stamped on each engraving, Heber’s note of purchase from the White Knights sale, and stamp of Isaac C. Bates’).

35. Brinsley Ford, Charles Avery and John Mallet, ‘Richard Ford (1796-1858)’ in The Volume of the Walpole Society 60 (1998), p.26: ‘Two of the most beautiful books in the library were given by Lord Essex to Richard Ford in 1827 – the two volumes of etchings by Ian Bisschop published in The Hague in 1671… These volumes belonged to Sir Peter Lely, since each plate bears his collector’s mark. On Lely’s death the volume passed to P.H. Lankrink who also added his collector’s mark to all the plates…’. Cf. Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’, op. cit., pp.137-138 (‘every individual page has the PL stamp, North’s numbering system appears just once on the title-pages’).

36. In one album (British Museum, L,67.1-33; 164.a.2), the impressions are ‘inlaid into sheets which are in an English or Dutch gold-tooled binding of the first two decades of the XVIIIc’ (link). Lely’s genuine monogram is on fourteen prints; a pen imitation of his monogram has been added to the other eighteen. The album was purchased by Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode at the Duke of Argyll sale, 21 May 1798 (lot 330), and was bequeathed to the British Museum in 1799. The other album (M.44.2-33; 164.b.1) is bound ‘in Russia tooled leather of the XVIIIc’ (link); five prints in it have Lely’s genuine monogram. See Anthony Griffith’s note, ‘False margins and fake collector’s stamps’ in Print Quarterly 13 (1996), pp.184-187 (binding on 164.a.2 reproduced as fig. 136).

37. Spiering, who was in London with two of his daughters, died of a sudden illness on 19 February; the possessions that he had with him are said to have returned to Holland with his family. See Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1651-1652, edited by Mary Anne Everett Green (London 1877), p.551, for a warrant of the Council of State, issued ‘For transportation of the body of Peter Spiering, Lord of Silverchrone, late agent from the Queen of Sweden, his train and household stuff’; and pp.145-146, for an order of the Council of State to the Navy Commissioners, appointing a frigate ‘as convoy to the ship which carried over the body of Lord Spiering, minister from the Queen of Sweden, who died here, with his family and goods’ (link).

38. Ilja M. Veldman, ‘Portrait of the artist as an art collector: Pieter Spiering van Silvercroon’ in Simiolus 38 (2015-2016), pp.228-249 (p.242, citing this volume). In the 1670s, Spiering’s son and heir, Johan Philip Silvercroon, sold various volumes.

39. Jan Gerrit van Gelder and Ingrid Jost, Jan de Bisschop and his Icones & Paradigmata: Classical Antiquities and Italian Drawings for Artistic Instruction in Seventeenth Century Holland (Doornspijk 1985), pp.202-203 note 30: ‘once owned by Sir Peter Lely whose collector’s mark (L. 2092) is to be found on all sixty-five illustrations in the book’.

40. British Museum, 1893,0411.15.1-151 (link). Lely also owned a set of Tempesta’s Septem orbis admiranda (1608), which passed afterwards into the collection of Richard Houlditch, and is now British Museum, 1928,0313.57-63 (link); these impressions are trimmed to the image, and probably were extracted from one of Lely’s portfolios. Twelve prints from two series of Tempesta’s hunting scenes (V, VII), similarly trimmed to the images, are British Museum, 1848,1125.54-61, 63-64, 67, 71 (link). Lely’s set of Jacques Callot’s series of hunchbacked figures and grotesque dwarfs, Varie figure gobbi di Iacopo Callot fatto in firenza l’anno 1616, likewise trimmed, is British Museum, X,4.439-459 (link). According to Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’, op. cit., p.128, that suite was once bound (‘[Lely] also owned… a bound volume of Callot’s Varie Figure Gobbi’).

41. For a specific instance of the artist’s use of this repertoire, see David Ekserdjian, ‘A Portrait by Lely and a drawing after Correggio: An artist's use of his collection of drawings’ in Apollo 147 (1998), pp.28-29. A drapery study in pencil on the verso of one of the plates of Historia septem infantium de Lara (Checklist B-5) is evocative of studio use.

42. Saken van staet en oorlogh, in ende omtrent de Vereenigde Nederlanden (in 14 quarto volumes, The Hague 1657-1671; reprinted in folio, The Hague 1669-1672). North, Life of the Lord Keeper North, op. cit., p.45: ‘[Lely] recommended to his Lordship the reading of a voluminous work, ‘tituled Saken van Staten, as if that had been a code of all manner of knowledge…’.

43. Evelyn inscribed another copy of this book ‘For Mr Wright, from his most humble servant J. Evelyn’ (Puttick & Simpson, Catalogue of rare and valuable books, etc., from the private collection of Basil Montague Pickering, Esq., and other sources, London, 28 May 1879, lot 139 – to Pearson, £3-5-0).

44. The second part of a corrected and enlarged second edition of Browne’s Ars pictoria: or An academy treating of drawing, painting, limning, etching, licensed 10 May 1675. The dedication ‘To My Worthy and Honoured Friend, Peter Lely, Esq. Painter to His Majesty of Great Britain, &c’ (link) cancels one to Sir William Ducie.

45. Millar, op. cit., p.70 no. 56.

46. The library at Lamport Hall was built up over several generations and contained many extraordinary rarities of Elizabethan poetry and prose, discovered there in 1867, and sold in 1893 to Wakefield Christie-Miller of Britwell Court and to the British Museum. A further portion of the library, including this volume, was sent to Sotheby’s in 1904.

47. The binder has employed for the endleaves a paper from the Durand mill in Normandy: in seventeenth-century England, the name Durand ‘was a symbol of excellent “Paper out of France”’ (Alan Stevenson, in Charles Moïse Briquet, Les filigranes, Amsterdam 1968, I, p.*35). The large watermark featuring the arms of France and Navarre, a Maltese cross beneath, and subscript ‘A Durand’, is similar (but not identical) to Edward Heawood, Watermarks, mainly of the 17th and 18th centuries (Hilversum 1950), nos. 661 (c. 1673), 678 (1680); and to Heawood, ‘Further notes on paper used in England after 1600’ in The Library, fifth series, 2 (1947-1948), p.144 no. 22 (Raleigh’s History 1677). An earlier a paper with the same arms and subscript ‘A Durand’ is in the Folger Library, E. Williams watermark collection, L.f.733 (Letter of attorney, 15 July 1651; link).

48. Compare the monograms on Lely’s drawn portrait of his son John and daughter Anne, respectively British Museum, 1874,0808.2264 (link) and 1874,0808.2265 (link); and a portrait of a girl, drawn in the late 1650s, British Museum, 1983,0723.35 (link; Lindsay Stainton and Christopher White, Drawing in England from Hilliard to Hogarth, catalogue of an exhibition held at the British Museum, London, June-August 1987, London 1987, pp.123-124 no. 88).

49. Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1655-6, edited by Mary Anne Everett Green (London 1882), p.583: passport ‘For Peter Lely and Hugh May, his servant, to Holland, on request of Lord Strickland’ (link). John Bold, ‘May, Hugh’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, Jan 2008, accessed 22 November 2016), states the purpose of their visit ‘to join the exiled court’.

50. According to a near-contemporary account, however, Gaspars did not enter Lely’s studio until after the Restoration. Cf. Bainbrigg Buckeridge, ‘An Essay towards an English-School, with the lives and Characters of above 100 painters’ in Roger de Piles, The art of painting, and the lives of the painters (London 1706), p.400 (link). The Executors’ accounts record a payment on 22 December 1681 ‘To Mr Baptist for praising the collection with Mr Walton… 2-3-0’ (British Library, Add Ms 16174, f. 29 verso).

51. Several years earlier, in 1652, Peter Lely and his sister had jointly inherited a property in The Hague from an aunt, Odilia van der Faes. Catharina Maria was a beneficiary of Lely’s will.

52. Taylor, ‘Lely in Arcadia’, op. cit., pp.63-85 (pp.65-69, ‘Painterly and literary influences’).

53. ‘A Historical and technical Investigation of Sir Peter Lely’s Cimon and Efigenia from the Collection at Doddington Hall’ in Researching The Courtauld Collections: Conservation and Art-Historical Analysis, Courtauld Institute of Art Research Forum (London: Courtauld Institute of Art, 2014), p.3 (link).

54. Caroline Campbell, in Peter Lely: a lyrical vision, op. cit., p.132 no. 11.

55. The Dutch publishing house perhaps supplied books to Lely, as the Executors’ account book records a ‘debt due on acct. from the Elzevirs in Holland… 21-7-6’ (British Library Add Ms 16,174, fol. 52 verso).

56. Dethloff, ‘Sir Peter Lely’s collection of prints and drawings’, op. cit., pp.131, 133.

57. Howard M. Nixon, English Restoration bookbindings: Samuel Mearne and his contemporaries (London 1974), pp.32-34, nos. 56-64; H.M. Nixon, ‘Queens’ Binders A & B’ in Sotheby Parke Bernet & Co., Catalogue of valuable books, London, 16-17 November 1981, pp.53-55 (rubbings of 21 and 10 tools associated respectively with Queens’ Binders A and B); H.M. Nixon, Catalogue of the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. Volume 6: Bindings, compiled by H.M. Nixon (Cambridge 1984), plates 40-43.

58. The Henry Davis gift: a collection of bookbindings. Volume II: A catalogue of north-European bindings, compiled by Mirjam M. Foot (London 1983), pp.154-155 no. 117 (Davis 197-198) (image source).