View larger

View larger

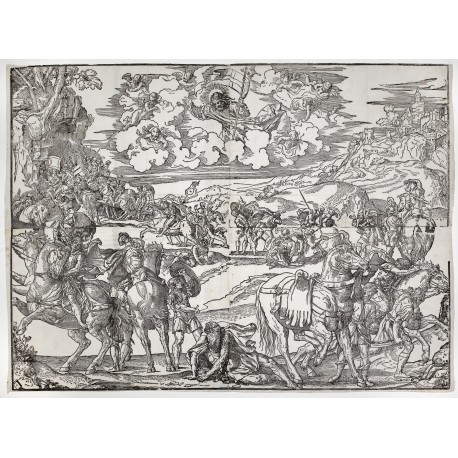

Conversion of Saint Paul

Ten complete impressions and three fragments of this print are known, of which at least four were printed in the seventeenth century. This impression is on a watermarked paper produced at mills in the Trentino and Friuli, c. 1580-1587.

- Subjects

- Prints - Artists, Italian - Monogrammist LA (Lucantonio degli Uberti?)

- Authors/Creators

- Monogrammist LA (Lucantonio degli Uberti?), active c. 1489-1520

- Artists/Illustrators

- Monogrammist LA (Lucantonio degli Uberti?)

- Uberti, Lucantonio degli, c. 1457-1520

- Owners

- Heseltine, John Postle, 1843-1929

- Poggi, Antonio Cesare, 1744-1836

- Other names

- Giunta, Lucantonio, died 1538

Monogrammist la (Lucantonio degli Uberti?)

Conversion of Saint Paul

[Venice], c. 1515-1520

woodcut, printed from four blocks on four sheets of paper, joined as dictated by the composition (dimensions overall: blocks 784 × 1047 mm; sheets 786 × 1070 mm).

paper laid paper, each sheet with watermark of trefoil with pendant Vd (similar to Briquet 662: Udine, dated 1587)1

provenance Antonio Cesare Poggi (1744-1836), London and Paris, his black ink stamp in lower left corner (Lugt 617; link)2 – John Postle Heseltine (1843-1929), his ink stamp on verso (Lugt 1507; link)3 – Christie’s, Old Master Prints, London, 14 December 2017, lot 82 (link)

condition printing cleanly and clearly, some gaps in borderline, some wormholes in the blocks touched with pen and ink, overall in good condition.

Hinged onto acid-free museum board, framed with uv-filtering acrylic glazing by Arnold Wiggins & Sons.

A four-sheet woodcut print representing the dramatic biblical account of Saul’s conversion on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:1-18). Woodcuts of this type, grand pictorial compositions printed from multiple blocks, were produced in Venice in the early decades of the sixteenth century to serve decorative, educational or devotional purposes. Customarily displayed on walls, or stored as large rolls, they soon deteriorated, and despite substantial print runs and multiple editions, few examples have remained intact through the centuries. Of this print, ten other complete impressions and three fragments are recorded (see provisional census of impressions).

According to present knowledge of the Venetian print market, the production of these monumental woodcuts was initiated by a commercial printer or print dealer, who would pay a designer for drawing his composition on the woodblock, or for providing a drawing that could be directly transferred to the block by a cutter. In a few instances, these individuals are named on the print, or in an ancillary document, such as an application for a privilegio (a kind of copyright). Here, the identities of both publisher and designer are unknown, and matters of scholarly debate.

The anonymous designer of the woodcut has assimilated elements from various sources, including a Quattrocento engraving of this subject attributed to Baccio Baldini.4 Saul, an elderly bearded man, dressed as a Roman soldier, lies in the centre foreground; the men who are journeying with him, on foot and on horseback, turn in all directions, shielding their faces from the light emanating from clouds at upper centre, in which Saul has seen a vision of the risen Christ. In the background at the left, a troupe of soldiers retreat into a wooded ravine; to the right, is a fortress in a mountain landscape.

The designer may have been active in the circle of Titian, whose vigorous graphic style he has absorbed to a high degree. Striking similarities with two multi-block woodcuts produced in Venice about 1515, and long associated with Titian as inventor – ‘The Sacrifice of Abraham’ and ‘The Submersion of Pharaoh’s Army in the Red Sea’ – are noted by David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro,5 Caroline Karpinski,6 Bert Meijer,7 and other critics, who conjecture near-contemporaneous dates of invention or execution. Indeed, the ‘Conversion’ might be one of the unnamed prints (‘altre hystorie noue’) included in a privilege granted for the ‘Sacrifice’ and the ‘Submersion’ to the publisher Bernardino Benalio, on 9 February 1515.8

Collateral evidence connecting the print with Titian is a letter written by the Flemish painter-humanist Dominicus Lampsonius to Titian, on 13 March 1567, in which he acknowledges Titian’s recent gift of a parcel of his prints, among them a ‘brava Conversione di S. Paulo’.9 Two woodcuts of the subject made in Titian’s lifetime are extant: this four-sheet woodcut, and a single-sheet woodcut ‘Conversion’. The smaller print is executed in a profoundly different style and is not generally associated with Titian.10

Designers of woodcuts did not usually cut the blocks themselves. During his long working life, Titian collaborated with various blockcutters, notably Giovanni Britto (c. 1500-after 1550), Nicolò Boldrini (active 1530-1570), and a cutter working much earlier in the century, Ugo da Carpi (active in Venice until c. 1518). Baseggio’s early assignment of the ‘Conversion of Saint Paul’ to Boldrini11 was sustained by Korn12 and by Gheno,13 and is enshrined in the online collection catalogues of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (link) and Rijksprentenkabinet in Amsterdam (link). In 1974, Susan Siegfried speculated that the cutter might be Ugo da Carpi, an attribution repeated by David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro,14 and again in the online collection catalogues of the British Museum (link) and Metropolitan Museum of Art (link).

These and other discussions of the print were centred on impressions in later states, where the small tablet in the lower left corner is empty. In early states, the cutter’s monogram l.a. appears on the tablet, a fact recorded long ago by Passavant, but largely overlooked.15 Passavant associated this monogram with the book publisher Lucantonio Giunta, a Florentine, active in Venice from the late 1480s (died there in 1538). In 1911, G.F. Hartlaub drew attention to a fragment of the ‘Conversion of Saint Paul’ in the Segelken Collection in Kunsthalle Bremen, which bears the monogram l.a.* on the tablet in lower left corner (fig. 1).16 In 1976, Caroline Karpinski discovered another fragment with the monogram l.a in the Victoria & Albert Museum (fig. 2);17 simultaneously, a trimmed impression of the complete print, with an illegible monogram, was published by Christian von Heusinger (fig. 3).18

The Monogrammist la: Lucantonio degli Uberti?

Comparative illustrations

Fig. 1 Detail from fragment in Kunsthalle Bremen19

Fig. 2 Detail from fragment in Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 3 Detail from complete impression in Kunstmuseum Basel20

Convinced by arguments presented by Paul Kristeller in 1897,21 both Hartlaub and Karpinski presumed the individual hiding behind the monogram l.a. to be Lucantonio degli Uberti, a native of Florence, active during the first two decades of the sixteenth century as a book and print publisher, woodblock cutter and intaglio printmaker. Kristeller had disentangled his work from that of Lucantonio Giunta, the Florentine publisher active in Venice to whom Passavant had credited the ‘Conversion of Saint Paul’, and A.M. Hind and others endorsed the distinction.22 Seventeen monograms (various forms of la*, la, lf, l) occurring on woodcuts in Venetian books were then associated with Lucantonio degli Uberti by Essling, who tracked their usage through numerous editions.23

In recent research, Lucantonio degli Uberti is revealed as an itinerant printer and print publisher, active at various times in Verona, Venice, and Florence, and perhaps also in Milan and Esztergom in Hungary. No evidence has yet emerged to dispel the traditional view of him as an aspiring printer-publisher, impecunious, and thus often obliged to cut blocks for his rivals.24 The vast number of book illustrations imputed to him by Essling is, however, surely due for correction: the stylistic range and the quality of these woodcuts is extreme, more than may be accounted for by the difference of designer, and the variety of monograms is not credible.

Comparative illustration

Fig. 4 Printer’s device of Lucantonio degli Uberti, signed lafe (Lucas Antonius Florentinus Excudebat)

Comparative illustration

Fig. 5 Printer’s device of Lucantonio degli Uberti and Bernardino Misinta, signed laf (Lucas Antonius Florentinus) and bm (Bernardinus de Misintis)

Lucantonio degli Uberti is first documented in Verona in 1481-1483, age 24, working for the printer Bonino Bonini.25 By 1489, he was in Venice, where he signed as ‘Luca Antonio Fiorentino’ (without his surname) three quartos in a short-lived partnership with Matteo Capcasa,26 and in 1498 an octavo under his own name alone.27 A folio, dated at Venice 17 August 1500, was perhaps first issued in Verona,28 where in 1503-1504 he published as ‘Lucas Antonius Florentinus’ nine books, modest quartos of a few quires, some jointly with Bernardino Misinta or Girolamo da Arcole.29 The latter editions were ornamented by the relevant version of a woodcut device of Fortune with her Sail, lettered lafe (Lucas Antonius Florentinus Excudebat) or laf | bm.30 These devices (figs. 4-5) and the blocks of several woodcut text illustrations may have been cut by Lucantonio degli Uberti himself.31

Comparative illustrations

Monograms on engravings associated with Lucantonio degli Uberti

Fig. a32 – Fig. b33 – Fig. c34 – Fig. d35 – Fig. e36

Sometime during this period, Lucantonio degli Uberti possibly returned to his native Florence and worked as a printmaker. Seven signed engravings – one imperfectly inscribed (Luc…tno), the others bearing his monogram la, laf (Lucas Antonius Florentinus), or laff (Lucas Antonius Florentinus Fecit) – and a number of unsigned engravings are ascribed to him, with the earliest dated c. 1500.37 A lost woodcut city plan of Rome, known only from an entry in the inventory of Ferdinand Columbus’s collection, apparently was lettered on a white-on-black tablet hanging from a tree with Lucantonio’s name, Florence as the place of publication, and date 1499.38 A large woodcut map of Florence, known as the ‘Pianta della catena’, or Chain View of Florence, based upon Francesco Rosselli’s lost engraving of 1482-1490,39 although unsigned, is generally accepted as Lucantonio’s work, and dated c. 1500-1510.40 It perhaps was not published in Florence, as the titles that identify some buildings on the print are in Venetian dialect.41

Lucantonio degli Uberti is next documented in Venice, where on 7 January 1513 as ‘Luca Antonio de Uberti fiorentino stampatore’ he was condemned for blasphemy (bestemmia) by the Council of Ten, and banished from the Republic for three years.42 Three prints suggest that he travelled north of the Alps during his exile. The first of these, known only from an entry in Ferdinand Columbus’s inventory, is a woodcut copy of Hans Burgkmair’s series of ‘The Seven cardinal Virtues’ (c. 1510), with lettering (on a tablet, beside Virtue) which the scribe renders as ‘opus Lucen Florentin con impresa in Milano’ (printed in Milan).

The second print is a copy in reverse of Hans Baldung Grien’s woodcut ‘Preparation for the Witches’ Sabbath’, printed as a chiaroscuro from two blocks, signed la* on a tablet hanging on the trunk of a tree, and dated 1516 in the key block (fig. q).43 The chiaroscuro technique had been invented by Burgkmair in Augsburg about 1508, and passed by blockcutters working in his studio to Strasbourg, where in 1510 Baldung executed his chiaroscuro woodcut of a ‘Witches’ Sabbath’. Did Lucantonio degli Uberti receive guidance in the new technique in Germany, from Baldung, or from another practitioner, or was observation sufficient for him to understand how it was made, and to produce this print?44

The third print is a woodcut copy of Antonio Pollaiuolo’s ‘Battle of the Nude Men’, lettered on a tablet hanging at left ‘Opvs lvce m florentini ed inplesa in stragva’.45 This garbled inscription is interpreted by Louis Waldman as ‘Opus luce An[tonii] Florentini ed[edita? editum?] impressa [impressum?] in Strigonia’, meaning that Uberti published it in Esztergom in Hungary. Waldman postulates, however, a visit by Lucantonio to the Hungarian court made during the mid-1490s, not twenty years later.46

Comparative illustrations

Monograms on woodcuts associated with Lucantonio degli Uberti

Fig. f47 – Fig. g48 – Fig. h49 – Fig. i50 – Fig. j51 – Fig. k52 – Fig. l53

When he returned to Venice, Lucantonio seems to have been occupied with the publication of woodcuts, which for a time he sold from a shop situated beside the Ponte San Moise. A small map of Lombardy signed ‘inmpressit venetis Lucas Antonius De Rubertis apde Ponte Dive Moises cum gratia’ was issued c. 1515-1525.54 Other prints signed by Lucantonio at Venice, but without this shop address, include a multi-block map of Italy (four sheets long by four wide);55 a map (or town plan, or view) of Constantinople (five sheets by four wide);56 a ‘Twelve Apostles and Christ’ (on seven sheets);57 and a pirated version of a woodcut series designed by Titian, known as the ‘Triumph of Caesar’ (on nine sheets).58

Lucantonio issued under his name – but without specifying their place of publication – a large-format woodcut of ‘Saint George and the Dragon’, lettered ‘Opvs Lvce A[n]tonii V[berti] F[lorentini]’ (on nine sheets);59 a woodcut of ‘The Ship of the Franciscans and the Dominicans’ (four sheets long by two wide);60 a woodcut of ‘The Twelve Labours of Hercules’ (six sheets long by two wide);61 and a map representing the province of Grenada (six sheets long).62

Comparative illustration

Fig. 6 Detail from woodcut book illustration (block reused in Lorenzo Spirito, Libro de la ventura, Venice 1544)

Comparative illustrations

Fig. 7 Details from woodcut book illustrations (from Girolamo Tagliente, Libro dabaco, [Venice c. 1520?])

Evidence of continued activity as a book publisher are two editions, both undated. One is Lorenzo Spirito’s Libro de la ventura, featuring a full-page woodcut wheel of fortune within a white-on-black floral border, signed with monogram l.a. with cross and star above the xylographic subscription ‘Inpreso i[n] venetis p[resso] lvchantonio uderti. a san moise i[n] pesina’ (fig. 6).63 The other book is Girolamo Tagliente’s Libro Dabaco… se chiama Thesauro uniuersale, with letters .la. cut in the title-block, and xylographic colophon ‘Opus lucha a[n]tonio de uberti fe[cit] i[n] uinetia’ (fig. 7).64

Comparative illustrations

Top row Fig. m Detail from woodcut book illustration, published 1514 – Fig. n Detail from single-sheet woodcut, dated 1517 – Fig. o Detail from multi-block woodcut, undated – Fig. p Detail from multi-block woodcut, c. 1517. Bottom row Fig. q Detail from single-sheet woodcut, printed in colour from two blocks, dated 1516 – Fig. r Detail from woodcut book illustration, published 1517 – Fig. s Detail from woodcut book illustration, published 152365 – Fig. t Detail from woodcut book illustration, published 152066

These monograms composed of the letters la with (and without) a star and cross, appear in numerous single sheet woodcuts and book illustrations. The monogram la is seen (with the cross, but without the star) in a cut of ‘The Betrayal of Christ’ in a book published by Lucantonio Giunta, 20 May 1514 (fig. m);67 a woodcut of a courtroom signed with the same monogram appears in three books published in 1522 by Gregorio de Gregori,68 and in two books published the same year by Battista Torti.69

The monogram la is seen (with a star, but without a cross) on a woodcut of ‘Virgin and Child seated between St. John the Baptist and St. Gregory the Great’, with publication line ‘Gregorius de gregoriis m.d.xvii’ (fig. n).70 A two-block woodcut of Christ on the Cross with Saints Francis of Assisi and Saint Jerome is signed l*a (fig. o).71 A two-block woodcut of the ‘Adoration of the Magi’ is signed on separate tablets with the name of its designer, Domenico Camagnola, and the cutter’s monogram la* (fig. p).72 A comparable monogram appears in a Breuiarium Patauiensis, published by Lucantonio Giunta for Leonhard and Lucas Alantsee, on 17 October 1517 (fig. q).73 An eight-block woodcut of ‘Martyrdom of the ten thousand Christians on Mount Ararat’ after an anonymous designer is signed l* (fig. r).74

Also attributed to Lucantonio are some blocks signed simply l.a. without either cross or star (figs. s-t), some of which are cut white-on black, or with a criblé ground. One such cut of dolphins and vase ornament, on a criblé ground, was utilised by the publisher Giorgio Rusconi, on 14 August 1512;75 another, of David with the head of Goliath, signed with white initials, was used by Peter Liechtenstein, in 1529, but probably was in use at earlier dates.76 Essling attributed to Lucantonio degli Uberti small woodcuts of Saint Anthony of Padua (signed la, lettered on a banderol ‘S. Antonio Padove’, with a city view lettered ‘Pado[v]a’), Saints Cosmo and Damian (signed l, lettered across background ‘S. Chosimo e S. Dami[ano]’), and Saint Stephen (signed la, lettered ‘Co[n] Grazia’), which are known only from re-impressions taken after mid-century.77

Provisional census of impressions

early states

Comparative illustrations

Fig. 8 Detail from fragment in Kunsthalle Bremen79

Comparative illustrations

Fig. 9 Detail from fragment in Kunsthalle Bremen

At present, two early states of the ‘Conversion of Saint Paul’ are known, both with the monogram of the cutter on the tablet in the bottom left corner (figs. 1-3). In the presumed first state, surviving uniquely in a fragment in Kunsthalle Bremen, two banderols are lettered respectively with the voice of Christ ‘Saule saule. Cur me p[er]seq[ue]ris’ (Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?) and with Saul’s reply ‘O D[omi]ne quid vis ut fa[ci]a[m]’ (Oh, Lord, what wilt thou that I should do?) (figs. 8-9). It is not evident from photographs whether these words were cut directly into the blocks, or on inserted plugs (small gaps in the design at the bottom end of the lower banderol might be caused by an ill-fitting plug, contracting over time).

In the other early state (fragment in Victoria & Albert Museum; complete impression in Kunstmuseum Basel), no banderols are featured. Were these sections cut out (or plugs extracted) and replacement plugs fitted to complete the composition? Other areas of the print appear to have been revised, and the possibility cannot be excluded that these ‘two early states’ are really an original and a very close copy printed from different blocks. All other known impressions of the print were taken from the set of blocks without the two lettered banderols. That composition was repeated exactly in a woodcut in the same direction and of a similar size, attributed to the Augsburg printmaker Jörg Breu the Younger (c. 1510-1547).78

● Basel, Kunstmuseum, Kupferstichkabinett, Inv. X.2528

762 × 1030 mm, joined (trimmed). Cutter’s monogram on the tablet (see above, fig. 3).

Presently catalogued as ‘Anonym, Italien, 16. Jh. / Lucantonio degli Uberti (zugeschrieben)’.

Provenance: Sammlung Birmann, 1847-185880

Literature: Horst Appuhn and Christian von Heusinger, Riesenholzschnitte und Papiertapeten der Renaissance (Unterschneidheim 1976), pp.32-34 (reproduced as fig. 24, the monogram not discernible); Caroline Karpinski, review of Titian and the Venetian Woodcut by David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro, in The Art Bulletin 59 (December 1977), pp.637-641 (p.637)

● Bremen, Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, Inv. no. 33029

Fragment (left half, only), 749 × 539 mm, joined. Cutter’s monogram on the tablet (see above, fig. 1). Inscribed on banners ‘Saule saule. Cur me p[er]seq[ue]ris’ and ‘O D[omi]ne quid vis ut fa[ci]a[m]’.

Presently catalogued as Monogrammist la, after Domenico Campagnola.

Provenance: Melchior Hermann Segelken (1814-1885) – acquired by the Kunsthalle in 1895

Literature: Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, ‘Die Sammlung des Doktors Segelken’ in Jahrbuch der bremischen Sammlungen 4 (1911), pp.113-128 (pp.119-120)81

● London, Victoria & Albert Museum, Bernard H. Webb Bequest, Inv. E. 4176-1919 (link)

Fragment (lower left sheet only), c. 430 × 530 mm (irregular). Cutter’s monogram on the tablet (see above, fig. 2).

Presently catalogued as Lucantonio Giunta, after Domenico Campagnola.

Provenance: Giuseppe Storck (1766-1836; Lugt 2318, link), inscribed on verso: ‘G. Storck a Milano 1803 | In. No. 13013’

Literature: Caroline Karpinski, ‘Some woodcuts after early designs of Titian’ in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 39 (1976), pp.258-274 (p.268 note 47)

presumed intermediate states

Fig. 10 Details showing damage to the blocks caused by woodworm

Left and centre Early states (Kunsthalle Bremen; Victoria & Albert Museum) Right Intermediate state (our impression)

Fig. 11 Details showing damage to the blocks caused by woodworm

Left and centre Early states (Kunsthalle Bremen; Victoria & Albert Museum) Right Intermediate state (our impression)

In these states, the tablet in lower left corner is blank. Over time, the blocks suffered from worming and cracking, and impressions show more signs of wear. Impressions here designated ‘intermediate states’ were taken at various times later during the sixteenth century.

● Bassano, Museo Civico, Gabinetto delle stampe e dei disegni, II-6-6

775 × 1035 mm, joined.

Provenance: Gian Maria Sasso (1742-1803) – Antonio Remondini (1752-1832)82 – donated to the Comune in 1849 by his son, Giambattista Remondini

Literature: Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat, ‘Tizian-Graphik: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte von Tizians Erfindungen’ in Die Graphischen Künste, Neue Folge, 3 (1938), p.14 fig. 4; Antonio Gheno, ‘Nicolò Boldrini vicentino, incisore in legno del secolo xvi’ in Rivista del collegio araldico 3 (1905), p.342-349 no. 44; Michelangelo Muraro and David Rosand, Tiziano e la silografia veneziana del Cinquecento, catalogue for an exhibition presented by the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, in 1976 (Vicenza 1976), p.89 no. 16 (reproduced)

● Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of W.G. Russell Allen, 52.1089 a-b (link)

792 × 1060 mm, joined and framed (1051 × 1299 × 19 mm). ‘Loss in lower right corner ca. 3 × 5 cm’ (Siegfried).

Presently catalogued as Nicolò Boldrini (‘formerly attributed to Domenico dalle Greche’), after Titian.

Provenance: Friedrich August ii, King of Saxony (1797-1854), inkstamp Lugt 971 on recto (link) – C.G. Boerner, Kupferstiche, Radierungen und Holzschnitte des xv. – xvii. Jahrhunderts aus der Sammlung König Friedrich August ii. von Sachsen (gestorben 1854) und aus zwei alten fürstlichen Sammlungen, Leipzig, 14-15 November 1933, p.129 lot 1089 (catalogued as anonymous, ‘Wohl nach Tizian’; 790 × 1050 mm, ‘Ausgezeichnet und vollständig, nur die rechte untere Ecke beschädigt. Alt aufgezogen’; link) – William G. Russell Allen (1882-1955) – his gift to MFA83

Literature: Susan Siegfried, in Rome and Venice: Prints of the High Renaissance, catalogue of an exhibition, edited by Konrad Oberhuber, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 5-30 May 1974 (Cambridge, ma 1974), pp.91-93 no. 56 (as cut by Ugo da Carpi, after ‘an artist working under Titian’s influence whose style remains essentially old-fashioned, such as the art of Palma Vecchio’); David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro, Titian and the Venetian woodcut: a loan exhibition, held at the National Gallery of Art, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, and the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1976-1977 (Washington, dc 1976), pp.111-113 no. 13; Patricia Meilman, ‘Titian studies Raphael’ in Source: Notes in the History of Art 3 (Winter 1984), pp.53-59 (p.58 fig. 6, as a woodcut by Lucantonio degli Uberti)

● London, British Museum, 1935,0713.1 (link)

790 × 1060 mm, joined and framed. Lower right corner of the bottom right sheet (block 4) made up with new paper, and the design improvised in pen and ink.

Present cataloguing: ‘Rosand & Muraro suggest an attribution of the cutting to Ugo da Carpi’, ‘certainly not after Titian’.

Provenance: reputedly John Postle Heseltine (1843-1929) – Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the well-known collection of engravings and etchings of the late J.P. Heseltine, Esq., London, 3-5 June 1935, lot 535 (included among ‘Framed old master engravings’, lots 513-538) – [vendor] P. & D. Colnaghi & Co.

● New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 49.95.147B (link)

Fragment (two left sheets, only), 780 × 528 mm, joined.

Presently catalogued as ‘attributed to Ugo da Carpi (Former Attribution: Nicolò Boldrini)’.

Provenance: Princes of Liechtenstein – [vendor] P. & D. Colnaghi & Co.

● Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans-Van Beuningen, D.N. 569/132

770 × 1050 mm.

Presently catalogued as Nicolò Boldrini.

Literature: Museum Boijmans-Van Beuningen, Venetiaanse prentkunst van Jacopo de’ Barbari tot Tiepolo, catalogue for an exhibition, March 1955 (Rotterdam 1955), p.26 no. 36 (as cut by Nicolò Boldrini); Museum Boijmans-Van Beuningen, Houtsneden, xve, xvie en xviie eeuw, catalogue for an exhibition, September 1957 (Rotterdam 1957), p.56 no. 168

late states

The number and distribution of wormholes identify impressions in late states. Some of the most heavily wormed impressions have a publication line printed outside the borderline of the lower left block, ‘In Venetia Il Vieceri’, alluding to a family of publishers documented across the Veneto in the mid-17th century. Francesco Vieceri was active at Belluno, Venice, Verona and Conegliano, from c. 1629 to c. 1661;84 while Lunardo, Felice, and Zuane Vieceri are listed at later dates in the ‘Mariegola degli stampatori e librai veneziani’.85 The same publication line is seen on impressions of the multi-block woodcut ‘Massacre of the Innocents’ (designed and perhaps executed by Domenico Campagnola, 1517),86 ‘Martyrdom of the ten thousand Christians on Mount Ararat’ (cut by Lucantonio degli Uberti, c. 1515-1520),87 and a three-sheet ‘Tabula Cebetis’.88

● Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, RP-P-OB-70.462 (link)

Presently catalogued as Nicolò Boldrini, after Titian.

Literature: Horst Appuhn and Christian von Heusinger, Riesenholzschnitte und Papiertapeten der Renaissance (Unterschneidheim 1976), p.34 (‘ein gleichfalls sehr später Druck’)

● Bremen, Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, Inv.no. 33030-33031

Four sheets, joined, 806 × 1088 mm. Late state with publication details in margin of lower left sheet: ‘In Venetia Il Vieceri’. Mounted on canvas.89

Presently catalogued as Monogrammist la, after Domenico Campagnola.

Provenance: Melchior Hermann Segelken (1814-1885) – acquired in 1895 by the Kunsthalle90

Literature: Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, ‘Die Sammlung des Doktors Segelken’ in Jahrbuch der bremischen Sammlungen 4 (1911), pp.113-128 (p.120: ‘Der zweite Zustand mit der Adresse des Vieceri ist in einem gröberen Abdruck vollständig vorhanden’; link).

● Paris, Fondation Custodia, Frits Lugt Collection, Inv. No. 1994-P.1

780 × 1050 mm. Watermark: initials cv (compared by Meijer with Briquet 9368, dated Milan 1526). Impression with publication line ‘In. Venetia *Il. Vieceri’ (outside borderline of lower left sheet).

Presently catalogued as ‘Lucantonio degli Uberti (?) (d’après Titien)’.

Provenance: [vendor] Paul Prouté sa, Catalogue 103: Dessins anciens et modernes: Estampes (Paris 1994), pp.28-29 item 127 (as cut by Ugo da Carpi after Jacopo Palma il Vecchio, reproduced)91

Literature: Bert Meijer, in Morceaux choisis parmi les acquisitions de la Collection Frits Lugt réalisées sous le directorat de Carlos van Hasselt, 1970-1994, edited by Mària van Berge-Gerbaud and Hans Buijs (Paris 1994), pp.148-149 no. 68; Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart's Renaissance: the Complete Works, catalogue for an exhibition, 6 October 2010-17 January 2011, edited by Maryan W. Ainsworth (New York 2010), p.354 fig. 281.

● Unlocated: ex-William Drummond (born 1934), sold 2017

Blocks and sheets 787 × 1053 mm. Publication line not present; numerous defects: ‘Printing unevenly and with wormholes in the block, with various losses, holes, tears and creases, in particular along the upper sheet edge, some stains, the sheets secured with thin Japan paper’ (Christie’s).

Literature: Christie’s, Old Master Prints, New York, 25 January 2017, lot 78 (link)

undetermined states

Information could not be obtained for these impressions:

● Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (?)

Later state, without cutter’s monogram on tablet.

Literature: Pietro Zani, Enciclopedia metodica critico-ragionata delle belle arti: Parte Seconda, Vol. ix (Parma 1822), pp.221-222 (‘Ma ecco che dopo il mio viaggio di Parigi trovo appunto nel Gab. Reale la prova stessa qui nominata dall’Heinecken con al basso nell’angolo del primo foglio una pietra quadra col fondo bianco’)

● Unlocated: ex-Gottfried Winckler (1731-1795), sold 1803

Literature: Michel Huber, Catalogue raisonné du cabinet d’estampes de feu Monsieur Winckler, sale by Weigel, Leipzig, 1803, ii, p.1193 no. 5593: ‘Grande Taille de bois, Piece anonyme représentant la Conversion de St. Paul, immense composition, de 40 pouces de large, sur 30 de haut. Piece attribuée au Titien pour l’invention et même par quelques uns pour l’exécution’ (link)

● Unlocated: ex-David Laing, sold 1880

Literature: Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Catalogue of a collection of prints formed by the late David Laing, Esq., London, 21 February 1880, lot 89 (part-lot, including ‘The Conversion of Saint Paul (P.43) after Titian’)

references Carl Heinrich von Heinecken, Dictionnaire des artistes dont nous avons des estampes (Leipzig 1788), ii, p.300 (link); Giovanni Battista Baseggio, Intorno tre celebri intagliatori in legno vicentini (Bassano 1839), p.17 no. 1 (link); Johann David Passavant, Le Peintre-graveur contenant l’histoire de la gravure sur bois, sur métal et au burin jusque vers la fin du xvi. siècle (Leipzig 1864), vi, p.231 no. 43 (link); Wilhelm Korn, Tizians Holzschnitte (Breslau 1897), p.47 no. 3 (link); Antonio Gheno, ‘Nicolò Boldrini vicentino incisore in legno del sec. xvi’ in Rivista del Collegio araldico 3 (1905), pp.342-349 (p.349 no. 44); Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat, ‘Titian’s Woodcuts’ in Print Collector's Quarterly 25 (1938), pp.333-360, 465-477 (pp.341, 354, 476); Fabio Mauroner, Le incisioni di Tiziano (Padua 1943), p.72; Susan Siegfried, in Rome and Venice: Prints of the High Renaissance, catalogue of an exhibition, edited by Konrad Oberhuber, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 5-30 May 1974 (Cambridge, ma 1974), pp.91-93 no. 56; David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro, Titian and the Venetian woodcut: a loan exhibition, held at the National Gallery of Art, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, and the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1976-1977 (Washington, dc 1976), pp.111-113 no. 13; Michelangelo Muraro and David Rosand, Tiziano e la silografia veneziana del Cinquecento, catalogue for an exhibition presented by the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, in 1976 (Vicenza 1976), p.89 no. 16; Caroline Karpinski, ‘Some woodcuts after early designs of Titian’ in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 39 (1976), pp.258-274 (p.267 fig. 8; p.268 note 47); Caroline Karpinski, review of Titian and the Venetian Woodcut by David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro, in The Art Bulletin 59 (December 1977), pp.637-641 (p.637); Dino Casagrande, ‘Le xilografie ombreggiate di Luc’Antonio degli Uberti’ in Charta 14 (no. 79, November-December 2005), pp.34-38

1. Compare Charles-Moïse Briquet, Les Filigranes (Amsterdam 1968), i, p.47 no. 662 (as a countermark, representing the initials of the papermaker, opposite watermark of an Angel in a circle, with hands outstretched, a star above); Piccard-Online 21409 (Castelnuovo, Trentino, dated 1582), 21411 (Telvana, Valsugana, dated 1580).

2. A painter, Poggi arrived in England in 1769, and exhibited portraits at the Royal Academy in 1776; he subsequently became a dealer, initially in London, and after 1801 in Paris. Five auction sales of his property are recorded, in 1782, 1791, 1801, 1836 and 1873. See Camilla Murgia, ‘Transposed models: the British career of Antonio Cesare de Poggi (1744-1836)’ in Predella 34 (2014), pp.173-183.

3. Possibly the print offered by Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the well-known collection of engravings and etchings of the late J.P. Heseltine, Esq. of 91 Eaton Square, S.W., comprising old master engravings, engravings of the English and French schools, and modern etchings, London, 3-5 June 1935, p.63 as lot 535 (‘Titian: The Conversion of St. Paul, by N. Boldrini (Pass. 43), large woodcut’), sold to P. & D. Colnaghi. The same provenance is claimed for the impression in the British Museum (1935,0713.1; link); see provisional census of impressions below. On the dispersal of Heseltine’s collections, see Louise Campbell, ‘Drawing attention: John Postle Heseltine, the etching revival and Dutch art of the age of Rembrandt’ in Journal of the History of Collections 26 (2014) pp.103-115 (p.112 and notes).

4. Arthur M. Hind, Early Italian engraving: a critical catalogue (London & New York 1938), i, p.67 no. A.ii.10; Early Italian engravings from the National Gallery of Art, by Jay A. Levenson, Konrad Oberhuber, Jacquelyn L. Sheehan (Washington, dc 1973), p.16 and fig. 2-6; Susan Siegfried, in Rome and Venice: Prints of the High Renaissance, catalogue of an exhibition, edited by Konrad Oberhuber, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 5-30 May 1974 (Cambridge, ma 1974), p.92: ‘…The composition, with its symmetrical structure and row of large figures pushed to the front, recalls a Quattrocento mode of construction… The figure of a youth with his hand on the bridle of a horse rushing out at the right corresponds very well to a (reverse) figure in an engraved Conversion of Saint Paul from 1465 which Konrad Oberhuber has recently attributed to the Florentine Baccio Baldini. The unusual motif of horsemen galloping into a cave in the cliff, seen in the left background of the woodcut, is also found in this Florentine print’.

5. David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro, Titian and the Venetian woodcut: a loan exhibition, held at the National Gallery of Art, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, and the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1976-1977 (Washington, dc 1976), pp.111-113 no. 13; Michelangelo Muraro and David Rosand, Tiziano e la silografia veneziana del Cinquecento, catalogue for an exhibition presented by the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, in 1976 (Vicenza 1976), p.89 no. 16. The authors observe identical modes of drawing and cutting, figural motifs, and landscape elements in all three woodcuts.

6. Caroline Karpinski, ‘Some woodcuts after early designs of Titian’ in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 39 (1976), pp.268-272. Karpinski finds the same formal structure and a ‘counterclockwise movement around an empty centre’ in the woodcut ‘Sacrifice’, ‘Conversion’ and ‘Submersion’, as well as in Titian’s painted ‘Battle of Cadore’ (conceived in 1513, but not finished until 1538).

7. Bert Meijer, in Morceaux choisis parmi les acquisitions de la Collection Frits Lugt réalisées sous le directorat de Carlos van Hasselt, 1970-1994, edited by Mària van Berge-Gerbaud and Hans Buijs (Paris 1994), p.148: ‘La clarté de la composition, la grandeur de la conception et les autres correspondances avec deux gravures sur bois [Sacrifice d’Abraham et Passage de la mer Rouge] dessinées par Titien pendant cette période désignent donc cet artiste comme l’ inventor, peu après 1515, de la Conversion’. Siegfried, in Rome and Venice, op. cit., p.92, observed: ‘The Conversion of Saint Paul belongs to the vogue of monumental prints initiated by Titian’s early woodcuts and clearly reflects the experience of Pharaoh’s Destruction in the Red Sea…The fallen horse in the right background, for example, is based on the drowning horse in the lower left corner of Titian’s print; the cliff at the left also seems to recall the cliff looming in the back of Titian’s print’.

8. The privilege of 9 February 1515 (Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Collegio Notatorio, Reg. 17, Anno 1512-1515, folio 103 recto) was first published by Rinaldo Fulin, ‘Documenti per servire alla Storia della Tipografia Veneziana’ in Archivio Veneto 23 (1882), pp.84-212 (p.181, no. 196). See Christopher L.C.E. Witcombe, Copyright in the Renaissance: prints and the privilegio in sixteenth-century Venice and Rome (Leiden 2004), pp.97-99, on Benalio’s publishing activities.

9. Johann Wilhelm Gaye, Carteggio inedito d’artisti (Florence 1839-1840), iii, pp.243-245 no. ccxviii (link).

10. The unsigned single-sheet print (405 × 498 mm) is known by a single impression in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Cabinet des Etampes, Inv. Bc6 fol. 63. The designer has been variously identified as Titian, Domenico Campagnola, Aspertini, or Girolamo Genga, and the cutter as Lucantonio degli Uberti or Francesco de Nanto; see Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., p.20 (note 5), pp.111-112 (reproduced as fig. I-20), p.125 (note 6), citing the publications of Han Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat (1938) and Fabio Mauroner (1941).

11. Giovanni Battista Baseggio, Intorno tre celebri intagliatori in legno vicentini (Bassano 1839), p.17 no. 1 (link).

12. Wilhelm Korn, Tizians Holzschnitte (Breslau 1897), p.47 no. 3 (link).

13. Antonio Gheno, ‘Nicolò Boldrini vicentino, incisore in legno del secolo xvi’ in Rivista del collegio araldico 3 (1905), p.349 no. 44.

14. Siegfried, in Rome and Venice, op. cit., pp.91-93 no. 56. Compare Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., p.112; Murano and Rosand, op. cit., p.89.

15. Johann David Passavant, Le Peintre-graveur contenant l’histoire de la gravure sur bois, sur métal et au burin jusque vers la fin du xvi. siècle (Leipzig 1864), v, p.66 no. 17 (as by Lucantonio Giunta; link); op. cit., vi, p.231 no. 43 (among anonymous ‘Gravures sur bois italiennes… Additions à Bartsch’; link). Two earlier connoisseurs may have seen a monogram, but misread it. Pietro Zani, Enciclopedia metodica critico-ragionata delle belle arti: Parte Seconda, Vol. ix (Parma 1822), pp.221-222, records ‘… Al b. nell’angolo de 1.º f.º sopra una pietra quadra BdaS … [Annotazione] Le lettere però BdaS da me riportate mi fanno ragionevolmente sospettare, che non possa essere altrimenti del sopralodato Artefice, ma piuttosto di Baldassarre Peruzzi, detto volgarmente Baldassarre da Siena.’ (link). Carl Heinrich von Heinecken, Dictionnaire des artistes dont nous avons des estampes (Leipzig 1788), ii, p.300, writes ‘…C’est une grande composition de beaucoup de figures, bien dessinées, mais asses mal gravées, sans nom de Graveur. On voit au coin gauche en bas une espèce de tablette, qui est en blanc.’ (link). Although Heinecken clearly states that no monogram is present, he inexplicably entered the print into the œuvre of Domenico Beccafumi. Pietro Zani (op. cit., p.222) thus supposed that Heinecken had seen other impressions, which like the one known to him were lettered BdaS on the tablet. He concluded that Heinecken had interpreted these letters B da S as Beccafumi da Siena (link).

16. Bremen, Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, Inv. no. 33029. Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, ‘Die Sammlung des Doktors Segelken’ in Jahrbuch der bremischen Sammlungen 4 (1911), pp.113-128 (pp.119-120, link). A second impression in the Segelken collection, in a later state with empty tablet, was attributed by the collector to the cutter Domenico dalle Greche (active 1543-1548): Heinrich Segelken, ‘Alfred Tonnellé über die italienischen Holzschnitte der Manchester-Ausstellung im Jahr 1857’ in Archiv für die zeichnenden Künste mit besonderer Beziehung auf Kupferstecher 9 (1863), p.222 (link).

17. London, Victoria & Albert Museum, Bernard H. Webb Bequest, Inv. E. 4176-1919. The print is catalogued as the work of Lucantonio Giunta (online collection catalogue, link). Karpinski, ‘Some woodcuts’, op. cit., p.268 (note 47); Caroline Karpinski, review of Titian and the Venetian Woodcut by David Rosand and Michelangelo Muraro, in The Art Bulletin 59 (December 1977), pp.637-641 (p.637).

18. Basel, Kunstmuseum, Kupferstichkabinett, Inv. X.2528. Christian von Heusinger read the monogram as dc, which he interpreted as the draughtsman and cutter Domenico Campagnola; see Horst Appuhn and Christian von Heusinger, Riesenholzschnitte und Papiertapeten der Renaissance (Unterschneidheim 1976), p.32 fig. 24: ‘Domenico Campagnola (?): Die Bekehrung Pauli, um 1517 (76.5 × 103 cm, Basel)’. ‘Im Kupferstichkabinett Basel hat sich aber ein herrlicher Frühdruck erhalten, der nicht nur die Einzelheiten der Zeichnung, sondern auch das Monogramm in dem Täfelchen links unten überliefert. Das Täfelchen ist zwar knapp beschnitten, die Buchstaben darin müssen jedoch d c gelesen werden. Damit ist Tizian fortan aus der Diskussion ausgeschlossen und nur noch zu fragen, ob das Monogramm wirklich mit Domenico Campagnola aufgelöst werden darf oder nicht’ (p.34). For Campagnola’s monogram, see G.K. Nagler, Die Monogrammisten (Munich 1860), ii, pp.393-398 no. 1004 (link).

19. Image courtesy of Dr Christien Melzer, Kustodin Kupferstichkabinett, Zeichnung und Druckgraphik 15.-18. Jahrhundert, Kunsthalle Bremen, Am Wall 207, 28195 Bremen.

20. Image courtesy of Géraldine Meyer, Mitarbeiterin Kupferstichkabinett, Kunstmuseum Basel, St. Alban-Graben 10, CH-4010 Basel.

21. Paul Kristeller, Early Florentine woodcuts: with an annotated list of Florentine illustrated books (London 1897), pp.xl-xlv.

22. Arthur M. Hind, An Introduction to the history of woodcut (London 1935), ii, pp.452-455; Hind, Early Italian engraving, op. cit., i, pp.211-214; Giuliana Patellani, ‘Lucantonio degli Uberti’ in Quaderni del conoscitore di stampe 20 (January-February 1974), pp.46-55; Maria Cecilia Mazzi, ‘Degli Uberti, Luca Antonio’ in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 36 (1988), pp.173-174; Marco Menato, ‘“Lucantonio ritrovato”: Appunti bibliografici su Lucantonio degli Uberti alias Lucantonio Fiorentino’ in Paratesto. Rivista internazionale 10 (2013), pp.37-45.

23. Victor Masséna prince d’Essling, Les livres a figures vénitiens de la fin du xve siècle et du commencement du xvie: Troisième partie (Florence and Paris 1914), pp.247-249 (link); Menato, op. cit., p.44 (summary of editions).

24. Two critics regard such employment by rivals to be incompatible with Lucantonio degli Uberti’s own aspirations as a printer-publisher; see Michael Bury and David Landau, ‘Ferdinand Columbus’s Italian Prints: Clarifications and Implications’ in Mark P. McDonald, The Print Collection of Ferdinand Columbus (1488-1539) (London 2004), i, pp.186-196 (pp.192-193).

25. Gian Maria Varanini, ‘Nuove schede e proposte per la storia delle stampa a Verona nel Quattrocento’ in Atti e Memorie della Accademia di Agricoltura Scienze e Lettere di Verona 38 (1986-1987), pp.243-267 (pp.258-260); Fernanda Ascarelli and Marco Menato, La tipografia del ’500 in Italia (Florence 1989), pp.456-457; Menato, op. cit., p.37.

26. Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (istc), ii00047000 (26 November 1489), io00135000 (31 December 1489), ih00258000 (17 February 1489/1490). These books were formerly credited to Lucantonio Giunta; for their new assignment, see Paolo Veneziani, ‘Lucantonio ritrovato’ in Le fonti, le procedure, le storie: raccolta di studi della Biblioteca, edited by Leonardo Lattarulo (Rome 1993), pp.195-203; Menato, op. cit., p.38.

27. istc ib01208000 (image).

28. istc iv00195000. Colophon: Venetiis a Lucantonio florentino. Anno domini .M.ccccc, die xxvii. Augusti (image). ‘Lucantonio florentino’ was identified with Lucantonio Giunta by Dennis E. Rhodes, ‘Problemi di bibliografia veronese alle fine del Quattrocento’ in Atti e Memorie della Accademia di Agricoltura Scienze e Lettere di Verona 31 (1979-1980), pp.307-317 (p.315); see also Martin Davies and John Goldfinch, Vergil: a census of printed editions, 1469-1500 (London 1992), p.74 no. 83. For the new assignment to Lucantonio degli Uberti, and treatment of the edition as a postincunable, see the Indice generale degli incunaboli delle biblioteche d’Italia (Rome 1972), v, p.302 (‘[Verona… dopo il 1503]’); Veneziani, op. cit., pp.195-203.

29. Lorenzo Carpanè and Marco Menato, Annali della tipografia veronese del Cinquecento (Baden-Baden 1992-1994), i, pp.149-154 no. 1 (Edit 16, CNCE 3622), no. 2 (Edit 16, CNCE 54442), no. 3 (Edit 16, CNCE 57391), no. 4 (Edit 16, CNCE 51151), no. 5 (Edit 16, CNCE 29426; istc im00015500), no. 6 (Edit 16, CNCE 3623), no. 7 (Edit 16, CNCE 42515), no. 8 (Edit 16, CNCE 35834), no. 9 (not in Edit 16; copy formerly in Munich, Bayerisches Staatsbiblothek, 4 P.o.it. 382,48).

30. Edit 16, K345-V542, K346-V541. Paul Kristeller, Die italienischen Buchdrucker- und Verlegerzeichen bis 1525 (Strassburg 1893), figs. 345-346; Emerenziana Vaccaro, Le marche dei tipografi ed editori italiani (Florence 1983), figs. 541-542; Carpanè and Menato, op. cit., ii, pp.633-634 nos. 1-2.

31. Francesco Corna, Fioreto, published 2 March 1503 (Carpanè and Menato, op. cit., no. 2): title-page woodcut view of the city, fountain of Madonna Verona (111 × 128 mm), the arena (111 × 128 mm); Inamoramento et morte de Pirramo et Tisbe, published 1503 (Carpanè and Menato, op. cit., no. 3): Thisbe throwing herself on the sword with which Pyramus has killed himself (112 × 126 mm; Kristeller, Early Florentine woodcuts, op. cit., no. 334g, link); Le Malitie delle donne col governo de la famiglia, published [1504?]: three women speaking to a devil (113 × 122 mm; Kristeller, Early Florentine woodcuts, op. cit., no. 254c, link).

32. Fig. a: Monogram on ‘Salome with the Head of John the Baptist’. Mark J. Zucker, The Illustrated Bartsch, 25 (Commentary): Early Italian masters (New York 1984), hereafter TIB, no. 2520.002; Hind, Early Italian engraving, op. cit., i, p.213 D.III.2. Impression in Vienna, Albertina (link).

33. Fig. b: Monogram on ‘The Archer’. TIB 2520.006; Hind, Early Italian engraving, op. cit., i, p.214 D.III.5. Impression in London, British Museum, 1858,0417.840 (link); impression in Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ea 19 rés (Lambert, op. cit., no. 244, link).

34. Fig. c: Monogram on ‘Lion, Lioness, and Dragon fighting’. TIB 2520.005; Hind, Early Italian engraving, op. cit., i, p.213 D.III.4. Impression in London, British Museum, 1846,0509.12 (link).

35. Fig. d: Monogram on ‘Woman seated in a Landscape with Two Children embracing’. TIB 2520.004; Hind, Early Italian engraving, op. cit., i, p.213 D.III.3. Impression in London, British Museum, 1841,0809.87 (link); impression in Vienna, Albertina (link).

36. Fig. e: Monogram on ‘Profile Head of a Roman Emperor’. TIB 2520.007; Hind, Early Italian engraving, op. cit., i, p.214 D.III.6. Unique impression in London, British Museum, 1873,0809.619 (link). A similar monogram (without the ‘F’) on ‘Saint Sebastian’. TIB 2520.003; Hind, Early Italian engraving, op. cit., i, p.212; v, p.308 D.III. Add.7. Monogram not visible on impression in London, British Museum, 1863,0725.52 (link); see impression in Bibliothèque nationale de France, Eb 5 rés (Lambert, op. cit., no. 245, link).

37. Zucker, The Illustrated Bartsch, op. cit., pp.517-526 (2520.001-2520.007), is ‘unconvinced’ by former attributions of unsigned prints to Lucantonio degli Uberti; cf. M.J. Zucker, The Illustrated Bartsch, 24 (Commentary, 4): Early Italian masters (New York 1999), p.200 (2417.025), pp.203-209 (2417.027-2417.031), pp.222-226 (2417.040-2417.042), pp.230-232 (2417.045), etc.

38. Entered in the Inventory as a plan on ten sheets, plus 2½ sheets of images depicting the Emperors and the history of Constantine; the scribe renders the lettering on the tablet as ‘ympressa en Florencia per Lucha Antonio anno 1499’. McDonald, op. cit., ii, p.571 Inv. 3170; cf. i, pp.111-112.

39. Woodcut from eight blocks on eight sheets, mounted 57.8 × 131.6 cm. Unique impression in Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Kupferstichkabinett, I.N. 899-100 (image).

40. The attribution to Lucantonio degli Uberti is reinforced by an observation made recently by Caroline Elam, who noted that the padlock (lucchetto) at upper left of the print could be the printmaker’s visual signature (lucchetto meaning ‘Little Luca’). See Caroline Elam, Firenze bella: The Renaissance City View, The Bernard Berenson Lectures at Villa I Tatti, 13-20 April 2010 (Cambridge, ma, forthcoming), cited by Louis A. Waldman, ‘Octahedron Tattianum: ii. Lucantonio degli Uberti, “Albertus pictor florentinus”, and the Master of the Esztergom Virtues’ in Renaissance Studies in Honor of Joseph Connors, edited by Machtelt Israëls and Louis A. Waldman (Florence & Milan 2013), i, p.5.

41. Christian Hülsen, ‘Die alte Ansicht von Florenz im kgl. Kupferstichkabinett und ihr Vorbild’ in Jahrbuch der Königlich-Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 35 (1914), pp.90-112 (p.96); Giuseppe Boffito and Attilio Mori, Piante e vedute di Firenze: studio storico topografico cartografico (Florence 1926), p.20 (‘el’ for ‘il’, ‘c’ for ‘ch’, omitting concluding vowels); David Friedman, ‘“Fiorenza”: Geography and Represention in a Fifteenth Century City View’ in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 64 (2001), pp.56-77 (p.77), noting that Rosselli is documented in Venice in 1504 and again in 1508.

42. Witcombe, op. cit., p.106 (citing Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Consiglio dei Dieci, Parti Comuni, Busta 2).

43. Adam Bartsch, Le peintre graveur (Vienna 1808), vii, p.447 no. 1 (link); The Illustrated Bartsch, 13: Sixteenth century artists, edited by Walter L. Strauss (New York 1981), p.25. Impression in London, British Museum, 1852,0612.105 (link).

44. The first Italian chiaroscuro woodcut is generally assumed to be Ugo da Carpi’s print after Titian’s painting of Saint Jerome, dated c. 1516 with regard to Ugo’s petition before the Venetian Senate on 24 July 1516 for a privilege protecting his ‘invention’ of printing in chiaro et scuro. Segelken speculated that Ugo received his training from the Monogrammist l.a. (Hartlaub, op. cit., p.121); if this can be proven, then Lucantonio’s ‘Preparation for the Witches’ Sabbath’ most probably antedates Ugo’s ‘Saint Jerome’, and credit for introducing the chiaroscuro technique in Italy belongs to Lucantonio. See Elizabeth Savage, ‘A Printer’s Art: The Development and Influence of Colour Printmaking in the German Lands c. 1476-c. 1600’ in Printing colour 1400-1700: history, techniques, functions and receptions, edited by Ad Stijnman and Elizabeth Savage (Leiden 2015), p.102; E. Savage, ‘Inventing chiaroscuro: Lucantonio degli Uberti’s Copy of Hans Baldung, Preparation for the Witches’ Sabbath, 1516’ (in progress).

45. Unique impression in London, British Museum, 1927,0614.96 (link). Shelley R. Langdale, Battle of the nudes: Pollaiuolo's Renaissance masterpiece, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Cleveland Museum of Art, 25 August-27 October 2002 (Cleveland 2002), p.84 no. 6 (reproduced p.7).

46. Waldman, op. cit., pp.3-7, suggesting that in addition to his work as a printmaker, Lucantonio may have painted frescoes in the Archiepiscopal Palace of Esztergom.

47. Fig. f: Passavant, op. cit., v, pp.62-66 (‘Luc Antonio de Giunta’, link); Nagler, op. cit., iv, p.262 no. 894 (‘Luca Antonio de Giunta’, link).

48. Fig. g: Passavant, op. cit., v, pp.62-66 (‘Luc Antonio de Giunta’, link).

49. Fig. h: Passavant, op. cit., v, pp.62-66 (‘Luc Antonio de Giunta’, link); Nagler, op. cit., iv, p.268 no. 903 (‘Luca Antonio de Giunta’, link).

50. Fig. i: Passavant, op. cit., v, pp.62-66 (‘Luc Antonio de Giunta’, link); Nagler, op. cit., iv, p.268 no. 903 (‘Luca Antonio de Giunta’, link).

51. Fig. j: Bartsch, op. cit., vii, p.447, monogram no. 196 (link); Passavant, op. cit., v, pp.62-66 (‘Luc Antonio de Giunta’, link); Essling, op. cit., Troisième partie, p.248 (link).

52. Fig. k: Nagler, op. cit., iv, p.265 no. 896 (‘Unbekannter Formschneider’, link).

53. Fig. l: Nagler, op. cit., iv, p.264 no. 895 (‘Luca Antonio de Giunta’, link).

54. Novum Langobardie opus sunma diligenta; the date of the map is presumed to be 1515-1525, since the Battle of Marignano is mentioned, but not the Battle of Pavia. Impressions are in Rome, Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele; Milan, Raccolte delle Stampe ‘Achille Bertarelli’, AFCV, XLIX-323 (C.G. m. 16-28) (530 × 387 mm, image); Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Estampes et photographie, FOL-QB-201 (3) (image).

55. McDonald, op. cit., ii, p.570 Inv. 3162, the scribe rendering the lettering on a scroll hanging from a column as ‘Lucha Antho de Uberti floren. ympressum Venetis anno a nativitate MVVIIII 23 Decembris’.

56. McDonald, op. cit., ii, p.569 Inv. 3159, the scribe rendering the lettering hanging on a tree as ‘opera de Lucha Antonis Florentino ympressum Venecie’.

57. McDonald, op. cit., ii, pp.498-499 Inv. 2732, the scribe rendering the lettering on a tablet as ‘imprensis en Venetia per Lucca Antonio de Uberti Florentino’.

58. The first block is signed ‘Opus luce Antonii Rubertii i[n] venetiis i[m]presso’. Essling, op. cit., Troisième partie, pp.102-103, reproduced (link); Peter Dreyer, Tizian und sein Kreis: 50 venezianische Holzschnitte aus dem Berliner Kupferstichkabinett Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Berlin [1972]), pp.38-39 no. 1-iv; Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., pp.38 no. iii; Michael Bury, ‘The “Triumph of Christ” after Titian’ in The Burlington Magazine 131 (1989), pp.188-197; Caroline Karpinski, ‘II Trionfo della Fede: l’‘affresco’ di Tiziano e la silografia di Lucantonio degli Uberti’ in Arte veneta 46 (1994), pp.7-13; Bury and Landau, op. cit., i, pp.192-193.

59. Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, KKSgb5195; the joined sheets measure 859 × 1184 mm (image). Passavant, op. cit., v, p.64 no. 7 (link); Kristeller, Early Florentine woodcuts, op. cit., p.xlii (link). See McDonald, op. cit., i, p.108; ii, pp.481-482 Inv. 2656 and pp.521-522 Inv. 2825.

60. McDonald, op. cit., ii, pp.497-498 Inv. 2728, the scribe rendering the lettering on a tablet as ‘Lucca Antonio Pepite’.

61. McDonald, op. cit., ii, p.495 Inv. 2719, presumably separate images here joined to make a roll. The scribe has rendered the lettering on tablets on two prints as ‘Luca Antonio Florentino fratris eben’.

62. McDonald, op. cit., ii, p.568 Inv. 3151, the scribe rendering the lettering on a tablet as ‘ympresso por Lucha Antonis Florentino’.

63. Lucantonio’s own edition of this very popular work (first published in Perugia in 1482) is lost; the two earliest surviving Venetian editions were printed ‘per Giuanni Padouano & Venturin Roffinelli compagni, 1537’ and ‘per Venturino Roffinelli, settembre 1544’ (Edit 16, CNCE 61842 and 61843). Lucantonio’s woodcut is illustrated from a copy of the 1544 edition in Harvard College Library (Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, Typ 525 44.804) by Ruth Mortimer, Catalogue of books and manuscripts, Part 2: Italian 16th century books (Cambridge, ma 1974), ii, p.668; cf. Kristeller, Early Florentine woodcuts, op. cit., p.xl.

64. The earliest dated edition was printed at Venice in February 1515 (Edit 16, CNCE 67544); for comparison of the original and Lucantonio’s undated edition, see Baldassare Boncompagni, ‘Intorno ad un trattato d’arithmetica stampato nel 1478’ in Atti dell’ Accademia Ponificia de’ Nuovi Lincei 16 (1862-1863), esp. pp.204-209 (designating the latter as ‘Edizione C’, link). The blocks were reprinted by other publishers; compare Mortimer, op. cit., ii, pp.674-676 no. 489; A.W. Pollard, Italian book-illustrations and early printing: a catalogue of early Italian books in the library of C.W. Dyson Perrins (Oxford 1914), nos. 268-270, 290, 297-298 (describing editions issued c. 1548-1561). Digitised copies in Kansas City, Linda Hall Library (link) and Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (link).

65. Pietro Aron, Thoscanello de la musica (Venice: Bernardino & Matteo de Vitali, 24 July 1523). Essling, op. cit., Seconde partie (Florence & Paris 1909), p.379 (link) and Troisième partie, p.158 (link). The woodblock portrait possibly was commissioned by the author, who held the privilege for this work (Fulin, op. cit., p.198 no. 234; link).

66. Ibn Abī al-Rijāl, ʿAlī, Haly De iuditijs: Preclarissimus in in iuditijs astrorum Albohazen Haly filius Abenragel nouiter impressus [et] fideliter emendates (Venice: Lucantonio Giunta, 2 January 1520). Passavant, op. cit., v, pp.65-66 no. 15 (as Lucantonio Giunta; link); Essling, op. cit., Seconde partie (Florence & Paris 1909), p.61 no. 1381 (link). The woodcut is based on Giulio Campagnola’s engraving ‘The Astrologer’ dated 1509 (Konrad Oberhuber, in Early Italian engravings, op. cit., pp.391, 393-395, 400-401; impression in London, British Museum, 1845,0825.771, link).

67. Decretum Gratiani. Cum glossis Ioannis Theutonici (Edit 16 CNCE 133670); Essling, op. cit., Première partie, pp.523-524 no. 523 (reproduced, link). Image from copy sold by Bonhams, Law books: Property of LA Law Library, London, 5 March 2014, lot 18 (link).

68. Innocentius. Apparatus preclarissimi iuris canonici (1 April 1522; Edit 16 CNCE 74175); see Essling, op. cit., Seconde partie, p.432 no. 2135 (link). For usage of the same block by De Gregori on 23 May 1522, see Essling no. 2152 (link); for usage by De Gregori on 3 June 1522, see Essling no. 2151 (link).

69. Pietro Paolo Parisio, Commentaria super capitulo in presentia (20 May 1522; Edit 16 CNCE 70789); Essling, op. cit., Seconde partie, pp.438-440 no. 2147 (reproduced, link). For usage of the same block by Torti on 25 May 1522, see Essling, op. cit., Seconde partie, p.433 no. 2157 (link). Digitised copy in Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (link).

70. The impression in London, British Museum, 1927,0614.176 (link), was exhibited by Muraro and Rosand, op. cit., p.85 no. 13; Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., pp.106-107 no. 11 (impression in New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.50.209; cf. Museum online collection database, as ‘a deceptive reduced facsimile’; link); Dreyer, op. cit., pp.41-42 no. 2 (impression in Berlin). Essling, op. cit., Troisième partie, p.104 (reproduced, link), noting that Passavant (op. cit., v, p.63 no. 6; link) gives the date as ‘mdxii’ (in error, as Passavant’s source, R. Weigel’s Kunstkatalog, no. 5647, correctly states 1517; link).

71. Impressions are in Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1961-1200 (link, not illustrated); Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi (Antony de Witt, R. Galleria degli Uffizi: La collezione delle stampe, Rome 1938, p.10 no. 16106); Trieste, Biblioteca civica Attilio Hortis, 82986 (link). The woodblocks are in Modena, Gallerie Estensi, Fondo Soliani; see Maria Goldoni, in I legni incisi della Galleria Estense: Quattro secoli di stampa nell’Italia settentrionale (Modena 1986), pp.77-80 no. 22 (C. 190a-b), and Collection database, Inv. 4355 (link).

72. The print is credited to Lucantonio degli Uberti by Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., pp.128-131 no. 17 (reproducing the impression in Washington, dc, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1974.26.1, link); Muraro and Rosand, op. cit., p.96 no. 22 (reproducing the impression in Bibliothèque nationale de France: see Les premières gravures italiennes, Quattrocento – début de cinquecento: Inventaire de la collection du département des estampes et de la photographie, catalogue by Gisèle Lambert, Paris 1999, no. 731, link). Nagler, op. cit., iv, pp.264-265 no. 895 (as Lucantonio Giunta; link). Cf. Hartlaub, op. cit., p.120.

73. Edit 16, CNCE 29161. Essling, op. cit., Première partie, Tome ii, pp.346-348 (reproduced, link). Nagler, op. cit., iv, pp.265-266 no. 896 (link). Copy in Prague, National Library of the Czech Republic digitised (folio ++10, link).

74. The print is credited to Lucantonio degli Uberti by Hind, Introduction to a History of Woodcut, op. cit., ii, p.454; Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., p.116 no. 14; Muraro and Rosand, op. cit., pp.90-91 no. 18. Witcombe, op. cit., p.101 (impression in Princeton University Art Museum reproduced as fig. 10), speculates that the original print ‘was almost certainly larger’, and perhaps one of the ‘altre hystorie noue’ cited in the privilege obtained in 1515 by the Venetian publisher Bernardino Benalio. The impression held by Yale University Art Gallery, Everett V. Meeks Fund, 2000.27.1a-h, is digitised (image).

75. Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, Oratoriarum institutionum (Edit 16, CNCE 59364); the block is reproduced by Mortimer, op. cit., ii, p.582 no. 408. The copy in Biblioteka Gdańska, Hb 4763 2° adl. 1, is digitised (link).

76. Alonso Tostado, Tractatus contra sacerdotes (Edit 16 CNCE 49663); the block is reproduced by Mortimer, op. cit., ii, pp.692-693 no. 501.

77. Kristeller, Early Florentine woodcuts, op. cit., p.xl; Essling, op. cit., Troisième partie, pp.106-108 (reproduced, link).

78. Appuhn and von Heusinger, op. cit., pp.33-34 (impression in Basel, Kunstmuseum, reproduced as fig. 25); The New Hollstein: Jörg Breu the Elder and the Younger, compiled by Guido Messling and edited by Hans-Martin Kaulbach (Ouderkerk aan den Ijssel 2008), ii, pp.214-215 no. 12 (impression in Bremen, Kunsthalle, Inv. No. 33132-33135, printed from eight blocks and 712/734 × 1036/1062 mm when assembled, is reproduced). The impression in the British Museum (1856,0614.136, link) is described by Campbell Dodgson, Catalogue of early German and Flemish woodcuts preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum (London 1903-1911), ii, p.438 no. 16 (link).

79. Figs. 8-9: images courtesy of Dr Christien Melzer, Kustodin Kupferstichkabinett, Zeichnung und Druckgraphik 15.-18. Jahrhundert, Kunsthalle Bremen, Am Wall 207, 28195 Bremen.

80. Peter Birmann (1758-1844) and Samuel Birmann (1793-1847), proprietors of Peter Birmann & Söhne, Basel; see Paul Ganz, ‘Samuel Birmann und seine Stiftung’ in 63. Jahresbericht der Öffentlichen Kunstsammlung Basel 7 (1911), pp.19-33.

81. ‘Die Segelken-Sammlung besitzt nämlich zwei Blätter eines ersten Zustandes dieses Holzschnittes (Unika?), wunderschöne Abdrücke, die nur leider sehr schlecht erhalten sind. Sie zeigen links unten, wo aber die Ecke abgerissen ist, noch die Hälfte der unverkennbaren Marke unseres Monogrammisten [l.a.*].’ (link). Cf. Christian von Heusinger, ‘Die Segelken-Sammlung altitalienischer Holzschnitte in der Kunsthalle Bremen’ in Kunstgeschichtliche Studien für Kurt Bauch zum 70. Geburtstag, edited by Margrit Lisner and Rüdiger Becksmann (Munich & Berlin 1967), pp.93-100 (p.96).

82. Zani, op. cit., p.221, saw this impression in the collection of Sasso, and records its entry into the Remondini collection (link).

83. ‘Accessions, June 12, 1952 through October 16, 1952’ in Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 50 (no. 282, December 1952), p.85.

84. August Buzzati, Bibliografia bellunese (Venice 1890), pp.50-70. For a list of 30 of Francesco’s publications, see Servizio Bibliotecario Nazionale, opac (link).

85. Venice, Biblioteca Correr, Mss Cicogna 3044; Anna Santagiustina Poniz, ‘Le Stampe di Domenico Campagnola’ in Atti dell’Istituto Veneto di scienze, Lettere ed Arti 138 (1979-1980), p.314 no. 15 (citing the ‘Mariegola’ fol. 231, line 25°, for Zuane). Cf. Nagler, Die Monogrammisten, op. cit., v, pp.192-193 no. 951 (link); Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., pp.124-125 no. 10.

86. Impressions in London, British Museum, 1860,0414.120 (link) and 1878,0511.647 (link); Rosand and Muraro, op. cit., pp.118-119 no. 15.

87. Impression in London, British Museum, 1866,0714.53 (link).

88. An impression offered in Rudolf Weigel’s Kunstkatalog: Achte Abtheilung (Leipzig 1840), p.102 no. 9488 (link), is cited by G.K. Nagler, Neues allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon (Munich 1850), xx, p.228 (link). It is perhaps the three-sheet woodcut of which there are two impressions in the British Museum, one with (1895,0122.1206, link) and the other without a monogram (1860,0414.147, link); neither impression has the Vieceri publication line.

89. Details of the Bremen impressions kindly provided by Dr Christien Melzer, Kustodin Kupferstichkabinett, Zeichnung und Druckgraphik 15.-18. Jahrhundert, Kunsthalle Bremen, Am Wall 207, 28195 Bremen.

90. For details of the Segelken’s bequest, see Christien Melzer, ‘A rare early 16th century woodcut from a private collection in the Kunsthalle Bremen’ in Studi di Memofonte 17 (2016), pp.212-226 (on-line).

91. ‘…belle épreuve en tirage tardif avec de nombreux trous de vers et en bas à gauche l’adresse “In. Venetia Il Vieceri”, quelques taches et déchirures. Selon Muraro et Rosand, on ne connait de ce bois que des épreuves tardives. L’exemplaire reproduit (Museo Civico, Bassano) semble moins complet et moins bien tiré que le nôtre, avec toutefois moins de trous de vers et l’adresse que porte notre exemplare n’est pas citée’ (18 000 F).